ACTIVE OR PASSIVE?

‘I don’t try to be clever at all. The idea that I could see what no one else can is an illusion.’1

Daniel H. Kahneman, Nobel Laureate 2002

Once you have a good idea of your overall wealth plan and asset allocation policy you will need to make a third key decision: should you pursue an active or a passive investment approach or a combination of the two? Figure 10.1 sets out the key characteristics of each approach.

Figure 10.1 The three investment management approaches

Source: The Vanguard Group.

Active investment management

Active investment management is where a manager (or investor) aims to beat, rather than simply match, the return of an investment market or agreed benchmark. Active investment management can be at the asset allocation or stock selection level or a mixture of the two.

Market timing is where an investor makes bets about whether to place more or less in a particular asset class at any given time. For example, the manager might believe that UK equities are likely to provide a higher return over the next year than, say, UK gilts and as a result might increase their allocation to UK equities and reduce the allocation to UK gilts. A few years ago many investors were attracted to gold and increased exposure to this asset class because they thought it offered better return prospects than other asset classes such as equities and property.

Active stock selection is where the investor makes bets on whether to invest in certain sectors or individual holdings within an asset class, for example banking shares versus drug companies or Merck versus GlaxoSmithKline. In the past few years a lot of investors were attracted to companies that were paying high dividends rather than those that were paying little or no dividends, as a result of the turmoil that arose in world stock markets in the 2007–2009 period.

Passive investment management

Passive investment management is where the manager aims to closely match the returns of a market, benchmark or risk factor. This is achieved by buying either a representative sample of the underlying holdings or all the holdings in an index so as to replicate, as far as possible, the market. This approach is called indexation and is the most common form of passive management.

A smaller proportion of the passive management sector follows a slightly different approach, which is known as evidence-based investing. Managers of such funds do not attempt to replicate or follow traditional indices but instead seek to hold shares that reflect a particular risk characteristic. For example, a fund investing in smaller companies may use a different definition of what is a smaller company compared with the established indices and also may adopt a more flexible approach to trading than an index fund that has to rigidly follow the benchmark index.

Core and satellite investing

This approach aims to deliver the benefits of passive and active management. The portfolio comprises a core of long-term investments and a periphery of specialist or shorter-term holdings (see Figure 10.2). Core investments are usually represented by long-term, low-cost index funds that closely track an index such as the FTSE All-Share. Satellite investments usually include specialist investments that are not highly correlated with core investments. Examples of satellite funds include hedge funds, commodities, thematic and emerging market equities.

Figure 10.2 Example of core and satellite allocation

Source: The Vanguard Group.

The efficient market hypothesis

A key concept to understand is what is known as the efficient market hypothesis. This is a model that was developed back in the 1960s to understand how investment markets behave.

Basically, the efficient market hypothesis2 states that:

- current prices incorporate all available information and expectations

- current prices are the best approximation to intrinsic value

- price changes are due to unforeseen events

- ‘mispricings’ do occur but not in predictable patterns that can lead to consistent outperformance.

The basic principle is that in an efficient market the current price of underlying securities reflects all publicly available information. As new information (news) comes to the market, prices immediately adjust to reflect that news, whether positive or negative. The implications of this hypothesis are that active management strategies cannot consistently add value through security selection and market timing, while passive investment strategies reward investors with capital market returns.

In 2008, when Lehman Brothers went bust, investors immediately changed their view of risks and returns, fearing an immediate collapse of the entire financial system, and prices adjusted to reflect this new scenario. By March 2009 investors had become even more negative and stock markets around the world had fallen to all-time lows. When the financial meltdown didn’t turn out as expected, investors’ appetite for risk returned and prices adjusted upwards.

So unless investors can predict the future or have (illegal) inside information, it is extremely difficult for them to do better than the market, certainly not consistently over any period of time. Traditional investment managers strive to beat the market by taking advantage of pricing ‘mistakes’ and attempting to predict the future. Too often, this proves costly and futile. Predictions go awry and managers miss the strong returns that markets provide by holding the wrong stocks at the wrong time. Meanwhile, capital economies thrive – not because markets fail but because they succeed.

As we discussed in Chapter 5, investment markets throughout the world have a history of rewarding long-term investors for the capital they supply. Companies compete with each other for investment capital and millions of investors compete with each other to find the most attractive returns. This competition tends to drive prices to fair value, making it difficult for investors to achieve greater returns without bearing greater risk. The futility of speculation is good news for the investor. It means that prices for public securities are generally fair and persistent differences in average portfolio returns are largely explained by differences in average risk. It is certainly possible to outperform markets, but not, in general, without accepting increased risk.

Testing times for the efficient market hypothesis

Behavioural scientists have been critical of the efficient market hypothesis, contending that investors’ irrational behaviour causes greed to lead to asset price bubbles and fear to lead to price crashes. However, the behavioural school seems to now agree that the most practical solution for most investors is to hold a diversified portfolio based on one’s lifestyle goals and tolerance for risk. Professor Richard Thaler is a leading member of the behavioural school and now thinks that the recent financial crisis has strengthened the efficient market hypothesis. In an article in the Financial Times, Professor Thaler explained his view:

‘While markets could make mistakes, it was still impossible to profit from how they were wrong … Lunches are not free. Shorting internet stocks or Las Vegas real estate two years before the peak was a good recipe for bankruptcy, and no one had yet found a way to predict the end of a bubble.’3

Concentrated risks can and do have big payoffs and so if you do want the highest returns possible, and can live with the highly probable consequences of failure, put all your eggs in the same basket, but watch that basket! The problem is that most concentrated risks are unlikely to be compensated. In other words, you are unlikely to be adequately rewarded for the risks that you take with such investments.

‘The four most dangerous words in investing are, It’s different this time.’

Sir John Templeton, legendary investor

Some commentators suggested that diversification failed during the financial crisis and ‘this time it is different’ and active asset allocation and stock selection are now key to investment success. All that the global credit crisis of 2008–2009 has proved is that markets can and do experience extreme price fluctuations in response to the rapid changes in economic conditions. The problem is that a large body of investors started to believe an outcome that was, statistically, likely to happen once in a lifetime, would happen in someone else’s lifetime, not their own. For example, in the 12 months ended 31 December 2008 American Express returned –63.67% while Wal-Mart returned +19.95%. So even in a market meltdown some companies will do much better than others. The problem is correctly, and consistently, picking the winners in advance.

In the summer of 2009, just a few months after world stock markets hit their historic lows, Professor Eugene Fama – the man widely considered to be the father of the efficient market hypothesis – had this to say:

‘The market can only know what is knowable. It can’t resolve uncertainties that are unresolveable. So there is a large amount of economic uncertainty out there, there’s going to be a large amount of volatility in prices. And that’s what we’ve been through. As far as I’m concerned, that’s exactly what you’d expect an efficient market to look like.’4

Harry Markowitz, an academic and Noble Laureate who is considered the father of modern financial economics with his theory of the efficient portfolio in the 1950s, had this to say about portfolio theory during the recent financial crisis:

‘During a crisis almost all securities and asset classes will move in the same direction. This does not mean that individual securities are no longer subject to idiosyncratic risks. Rather it means that the systematic risk swamps the unsystematic risk during this period.’5

Even large and apparently prosperous firms can fail. Take Enron, for example, which was, for many years, a star performer of the stock market and appeared to have a bright future. Within a matter of months the company imploded and filed for bankruptcy. Shareholders in Enron suffered a total loss of their capital. BP is another example of a massive company that got into difficulty when it suffered a major accident at one of its oil wells in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010. As a consequence of suspending dividends and uncertainty about the eventual compensation costs arising, the share price fell from around £6.50 before the accident to just over £3 within six weeks of the accident, as investors reassessed the risks associated with holding BP shares. One year later the shares stood at £4.50 as more information became available and BP resumed paying dividends, albeit at a lower level.

The folly of market timing

If it were possible to avoid the worst-performing investment days and capture returns from the best-performing days, then it would be possible to produce both positive returns all the time and significant outperformance of the market as a whole. It is the allure of these potential high returns that causes many investors, both professional and non-professional, to ignore the reality of market efficiency and to speculate on the future direction of markets. The evidence shows that markets experience gains often in short, unpredictable bursts. This means that it is easy for an investment trader to enter and leave the investment market at the wrong time. Sometimes missing just a few – usually the best – days in the stock market can result in significant long-term underperformance. For example, over a 27-year period (1986–2013), we can see in Figure 10.3 that missing the best 25 trading days would have cut the FTSE All-Share Index annualised compound return from 10.10% to 5.24%. Trying to forecast which days or weeks will yield good or bad returns is a guessing game that can prove costly for investors.

Figure 10.3 Missing the best days in the UK stock market

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors.

Market timing is challenging, as identified by a research study that looked at the US and UK stock markets from 1871 to 2004 and 1899 to 2004 respectively. The researchers compared a range of market-timing approaches to a simple buy-and-hold strategy. While market-timing techniques were found to work in identifying cheap and expensive markets, resulting in a return differential over a buy-and-hold strategy, investors are still better off with a buy-and-hold approach. This is what the authors had to say:

‘Our findings are not encouraging for proponents of active management using very long-run mean reversion: we find investors are inevitably better off with a simple buy-and-hold equity strategy rather than trying to time the market using moving average rules.

‘The returns from equities, even during the sub-optimal periods when they are expensive, have been markedly better than cash.’6

Bulls and bears

Investment markets have been described as voting machines in the short term, reflecting current sentiment based on news and other economic data, but weighing machines in the long term, reflecting the value of current and future earnings and dividends generated by companies. When stock markets are experiencing strong increases in valuation they are described as a bull market. When they are experiencing severe reductions in value then they are described as a bear market. When markets are not moving either up or down much they are described as ‘range bound’. History suggests that bull market cycles last longer than bear market cycles and produce cumulative gains that more than offset losses experienced in bear markets. Figure 10.4 shows the time and magnitude of those rises and falls for the UK stock market since 1955.7

Figure 10.4 The past 57 years of bull and bear markets

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors, the FTSE Group.

The chart in Figure 10.4 does not show total compounded returns or growth of wealth. Once the cycle is established in retrospect, the first month of that cycle resets the performance baseline to zero. Fluctuating performance within each trend illustrates that volatility and uncertainty occur even within established market cycles: bull markets may have short-term dips and bear markets may have short-term advances. The immediate trend is not readily apparent to market observers and may become clear only in hindsight. This analysis highlights the difficulty of accurately predicting and timing market cycles and the importance of maintaining a disciplined investment approach that views market events and trends from a long-term perspective. If you react emotionally to short-term movements, you are likely to make bad decisions that compromise long-term performance.

Do managers beat markets?

There is no credible evidence of persistence of success of active investment management and that success outperformance cannot, in the vast majority of cases, be explained by exposure to risk factors. One study examined 115 US equity mutual funds between 1945 and 1964 and found ‘very little evidence that any mutual fund was able to do significantly better than that which we expect from mere random chance’.8 Another study examined 4,686 US equity mutual funds between 1965 and 1998 and found ‘none of the styles included in the study are able to generate positive abnormal returns, compared to the Fama/French (1993) benchmark’.9

‘All the time and effort that people devote to picking the right fund, the hot hand, the great manager, have in most cases led to no advantage.’10

Peter Lynch, legendary US fund manager

A report prepared for the Norwegian government found that: ‘The average active return from January 1998 to September 2009 generated by Norges Bank Investment Management has been statistically indistinguishable from zero.’11 Another paper examined the empirical evidence and logic for investing using a passive approach in the UK by reviewing UK-based equity and bond funds over the 15-year period through to 31 December 2012. After deducting the results of all the funds that were closed in that period, only about 26% of UK equity funds beat the market and virtually no funds beat the market for UK-government bonds over ten years. The authors came to the following conclusion:

‘Actively managed funds have in the past tended on average to underperform their benchmarks and to underperform relative to low-cost passive funds targeting the same benchmark. For any period, there will inevitably be some fund managers within the total distribution that are nevertheless able to outperform, but the challenge for investors is to pick those fund managers in advance. Our results suggest that a lack of persistence of performance by specific funds makes it difficult to use past performance as a guide to future outperformance. This paper has shown that there is a compelling case for investors to invest in passive funds on the grounds that they provide higher returns on average and at lower volatility.’12

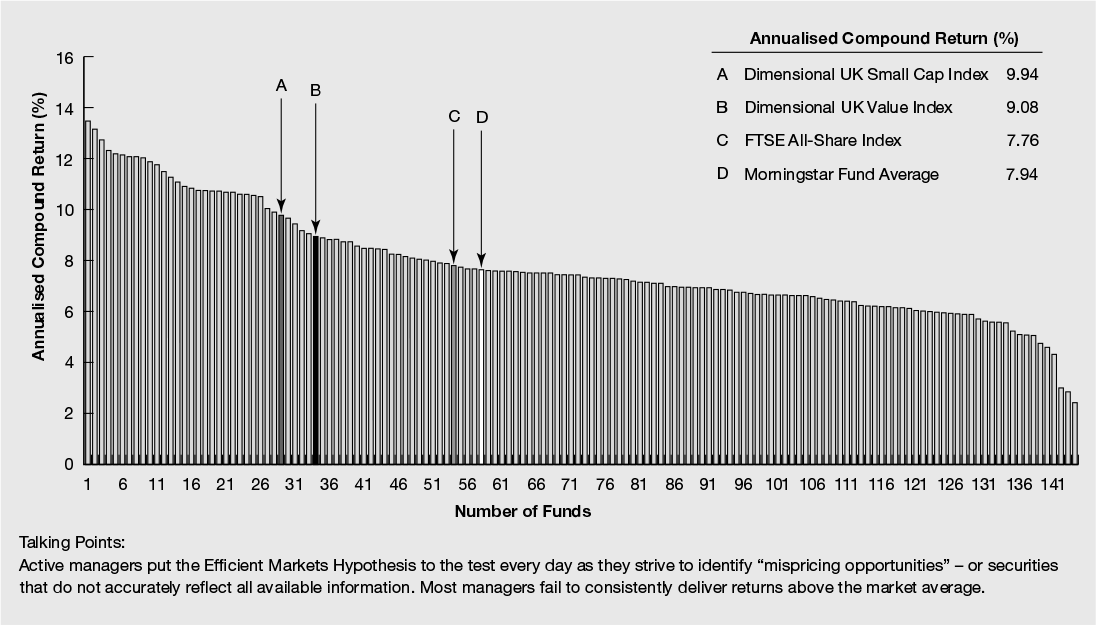

Time after time, analysis of past performance shows that the majority of active investment managers deliver returns below that of the market as a whole. Figure 10.5 shows the returns from more than 130 UK equity funds that existed over the 20 years to 31 December 2012. We can see that the majority of managers (and don’t forget that this excludes all the funds that failed to survive 20 years) underperformed the market as represented by the FTSE All-Share Index, which is consistent with the principles of efficient markets.

‘There are two kinds of investors, be they large or small: those who don’t know where the market is headed, and those who don’t know that they don’t know. Then again, there is a third type of investor – the investment professional, who indeed knows that he or she doesn’t know, but whose livelihood depends upon appearing to know.’

William Bernstein, US financial theorist and author

Due to the lower expected returns from fixed income, actively managed funds have to work particularly hard to generate market-beating returns, net of the additional ongoing and turnover costs. A recent analysis concluded that most of the historical outperformance of active global bond funds has been the result of risk which managers assumed beyond that of the bond benchmark. Once this excess risk exposure is taken into account, the relative performance of global bond funds is less favourable. The researchers showed that global bond index funds – and in particular, hedged global bond index funds – provide an attractive alternative to achieve the exposure of the asset class.13

What about less efficient markets?

Emerging markets are generally agreed to be less efficient than more liquid developed markets. The active management industry suggests that this should allow them to identify mispriced stocks and to manage the country- and stock-specific risks that investors are exposed to, such as the high state ownership of companies and resultant earnings highlighted above. This contention seems reasonable, but the empirical evidence suggests that a large percentage of managers – 80% over five years14 – fail to beat the emerging market benchmark. In part this is likely due to the annual expenses and trading costs incurred by actively managed emerging market funds. Trading costs have been estimated to be in the region of almost 140 basis points for a round-trip trade, which compares with that in developed markets (ex-UK) of around 35 basis points.15 It is possible to mitigate stock, country and active manager risk by owning a broad emerging markets fund, diversified across countries and stocks. For example, the MSCI Emerging Market Index covers around 2,700 companies across market capitalisation.

It’s not just bonds and equities for which a passive approach makes sense. A recent study16 revealed that of 80 active US real estate mutual funds (REITs), none of the managers, over a long sample period (1995–2008), exhibited stock-selection skill. The authors concluded: ‘The empirical findings show that even apparently successful funds ex-post display “poor” skill in that they perform significantly worse than they would be expected to simply due to luck.’

A passive approach seems the most reasonable one to adopt to capture the returns from global commercial property. Although there are relatively few products that provide the opportunity for gaining exposure to global commercial property on a passive basis, there are few OEICs and ETFs with costs in the region of 0.50% p.a. and below.

Luck versus skill

Random chance dictates that at any one time we would expect a small number of money managers to outperform the market average. The problem is they are rarely the same managers each time and picking the winning managers in advance is virtually impossible to do consistently. A large group of chimpanzees throwing darts at the share pages of the Financial Times has more chance of picking winning shares than a group of experienced equities analysts!

The issue of luck versus skill is rarely addressed in academic studies. A working paper from the respected finance professors Fama and French, however, looked at whether or not individual fund performance was distinguishable from luck.17 The key findings were that active managers show no statistical evidence they can enhance returns and they do not have enough skill to produce risk-adjusted returns that cover their costs. Only the top 3% of funds perform as well as might be expected if their true alpha (excess return) was not down to luck. A key conclusion of the authors was that ‘some [funds] do extraordinarily well and some do extraordinarily poorly just by chance’.

In his book The Wisdom of Crowds, James Surowiecki gives a good example of why the aggregate view is generally right more often than not.18 He cites an ox weight-judging contest held at the 1906 West of England Fat Stock and Poultry Exhibition. The average weight guessed by the 797 contestants was 1,197lb compared with the actual weight of 1,198lb. In another example, a Professor Treynor asked his finance class students to guess how many beans were in a jar. There were in fact 850 beans in the jar compared with the group estimate of 871. Only one of 56 students made a more accurate guess.

Winning the loser’s game

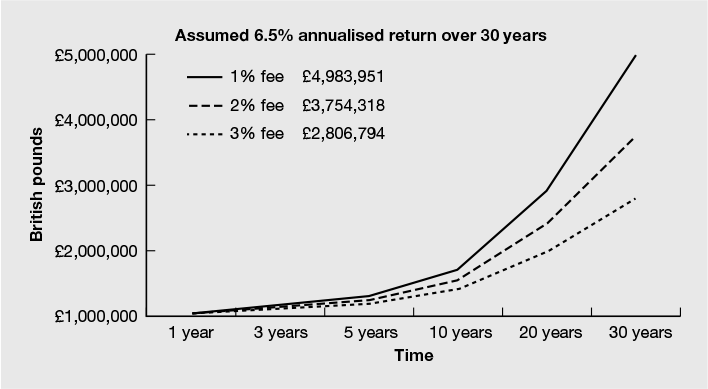

Active investment management is a zero-sum game before costs and a loser’s game after costs – for every winner there has to be a loser and costs reduce returns. In aggregate the maths does not support the proposition that there is a credible, reliable and replicable way of consistently outwitting the investment marketplace. None of us is smarter than all of us. Every penny that you save in costs is either more returns for you or you can take less risk to obtain the same level of return. See Figure 10.6.

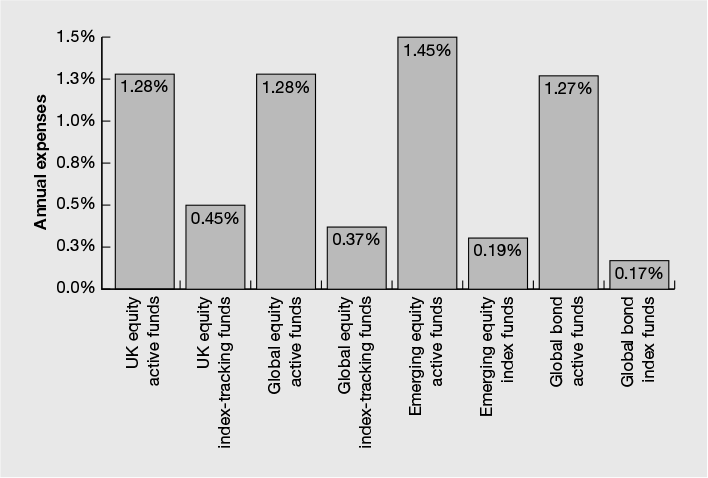

There are two main costs associated with investment funds: ongoing costs and turnover. Ongoing costs include things such as trustee and custodian fees. Turnover costs include the hard costs to the fund of buying and selling investments as well as the impact that buying and selling have on the price of the investments. Recent analysis (Figure 10.7) into the average expense ratio for various categories of index and actively managed open-ended investment funds shows that investors in actively managed UK equity funds were paying an average of approximately 1.28% annually versus 0.45% for index funds, a differential of 0.83% annually. The annual cost differential for overseas equity funds versus their indexed equivalents was even higher at 1.40% for European funds, 1.0% for euro zone funds, 1.13% for US funds, 0.91% for global funds and a staggering 1.27% for emerging market funds. Remember, these are weighted averages, so many investors will be paying even more than these relatively high amounts.

‘After costs, the return on the average actively managed dollar will be less than the return on the average passively managed dollar for any time period.’19

William F. Sharpe, 1990 Nobel Laureate

Figure 10.7 Value weighted annual expense ratios on open-ended investment funds

Source: Data from The Vanguard Group (2013) The case for index investing by UK investors.

The odds in terms of costs are so heavily stacked against active management it is no surprise that persistency of outperformance is so low. If you have to recoup an annual cost of c. 2.5% (comprising the annual charges and the effect of turnover within the fund) just to break even, then failure seems assured.

Charles Ellis, in his seminal book Winning the Loser’s Game, explained how to be an investing winner:

‘The objective of beating the market is in fact a loser’s game and that most people striving to beat the market actually have very unhappy experiences. They do not succeed. And, when I say most I’m not talking about 52% or 55%, I’m talking about 85 or 90%. So, the first part is do not play the game, you will not win, which is I’m going to beat the market, here I go. There’s an alternative where you can easily win and therefore I would call it a winning game. And, the winner’s game is what is it you’re really trying to accomplish, what would work really well for you? And, then go about that specific objective. And, each of us has different characteristics of what we’re trying to do. Sometimes the characteristics have to do with how long you’re going to stay invested. If you’re investing for the very, very long time … I have a three year old, a six year old and two three year old boys as my grandchildren. Any investments that they’re making are investments for 80 years – that’s a long time. And, they can invest differently than could someone who was saving to buy a home or saving for college or saving for some other specific purpose that’s going to come up in a year or two. So, your time horizon’s number one.’20

The passive detractors

A research paper that, on the face of it, gives some support for active management analysed 31,991 UK mutual funds (excluding index funds) in 73 categories over 30 years through to February 2010, representing $7 trillion of assets.21 Returns before costs (which has the effect of flattering active management returns) were then compared with the appropriate indices (after removing obsolete funds) to identify whether or not active managers had delivered excess return over the market (known as alpha). The findings were that, of the 73 categories, active management was recommended in 23, passive in 22 and in 28 the case was neutral.

The author’s main conclusion was as follows:

‘Our studies have found that both types of investing have their strengths and weaknesses. It depends on the market segments and the economic climate. We believe investors should utilize a blend of both active and passive investing with the goal of optimizing their portfolio.’22

The first observation is the staggering fund selection choice faced by investors – nearly 20,000 funds, of which 12,000 failed to survive! Also, it is interesting to note that even on a gross performance basis (i.e. before deduction of costs), active management was not the preferred approach in many major categories: inflation-protected bonds, government bonds, world bonds, foreign equities, global real estate and commodities. If costs had been taken into account, the proportion of cases when active management would have been recommended would have been even lower. The conclusion that active and passive investing are not rivals but complementary is not justified by this paper and its somewhat biased approach.

A more recent piece of analysis presents results showing that the IMA UK All Companies series beat the ‘average’ index fund over one, three, five, ten years to 9 January 2014.23 The author makes some valid observations:

- The index performance is not the same as an index tracker fund’s performance due to costs and other tracking error inefficiencies.

- There are some shockingly priced and poorly managed tracker funds that hold material amounts of investors’ money.

- An example of such a fund is the Halifax UK FTSE All-Share Tracker that has returned a cumulative 89.6% over ten years (to 9 January 2014) compared with 129.6% for the FTSE All-Share Index.

- The FTSE All-Share beat the IMA UK All Companies series over ten years (not explicitly stated, but evidenced in the author’s return table).

- There are some very low-cost index funds with exceptionally good tracking error, such as those offered by Vanguard.

- As passive supporters focus on the average active fund versus the market, it is only fair to focus on the average passive fund in any analysis.

- The funds representing the IMA UK All Companies return series tend to have a bias to lower capitalisation stocks than the index.

There are, however, a number of points to take issue with in the analyst’s argument and conclusions:

- If an index fund could replicate the performance of the index, then it would have beaten the ten-year IMA UK All Companies return. Reality is not that far off.

- For example: Vanguard’s ability to deliver near market returns is exemplified in the returns of its UK index tracker fund, which since inception – 23 June 2009 to 30 November 2013 – delivered an annualised return of 15.67% net of fees versus 15.78% for the index – a difference of only 11 basis points p.a. or a little over 1% implied over a ten-year period.

- In terms of what the future may hold, looking at Vanguard funds in the US,24 the Admiral share class available to retail investors (which targets the return of the S&P 500 Index) delivered the market less 2 basis points per annum over the past ten years, which is a fantastic achievement. See Table 10.1.

- You cannot capture the returns of the IMA UK All Companies series unless you own all the funds in it – a practical nightmare.

- Picking winning active funds, ex-ante, is extremely difficult as performance rarely persists.

- But picking an excellent index fund, ex-ante, is relatively simple, as the Vanguard experience demonstrates.

Table 10.1 Vanguard delivers the bulk of the market return – US fund data

Source: Data from The Vanguard Group.

To have any credibility and meet normal academic rigour it is necessary to carry out a regression of the performance against known risk factors in the IMA UK All Companies series. The author did not do this and makes this point: ‘One potential flaw of using the UK All Companies sector as a means of comparison is the number of funds with a natural bias towards small and mid-caps. It could be argued that taking this view shows skill on behalf of the manager: active funds are also able to reduce their weighting to the mid-caps when they think that sector is due a fall, and our data shows that the mid-caps fall harder when markets correct.’

No further explanation or analysis was offered. Having an exposure to the size premium is not a function of active skill in market timing but of positioning the portfolio appropriately along the size continuum, as we have discussed earlier, so as to take advantage of this priced risk factor, using well-structured passive products. Lumping in FTSE 100 index funds with FTSE All-Share index funds and then comparing them with an unregressed index that has higher exposure to smaller and mid-sized companies is unsound. A regression analysis on the IMA UK All Companies series over the ten-year period gives an apples-to-apples comparison as to what returns would have been delivered by a passive alternative would have been more rigorous. The returns of different market cap indices during the ten-year period 2004 to 2013 are set out in Table 10.2.

Table 10.2 Annualised returns ten years to December 2013 of UK equity by market capitalisation

Source: The FTSE Group.

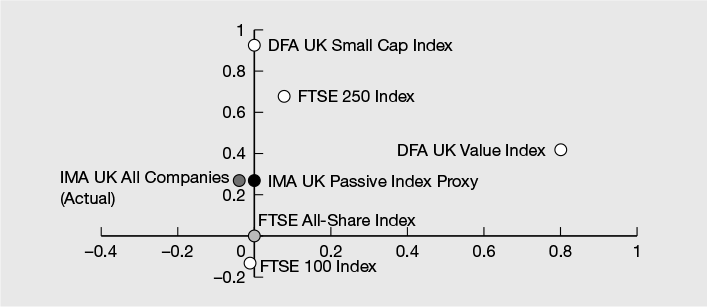

It is evident that any tilt to mid/smaller companies would have made a material impact on returns. Astute investors using passive funds can make strategic tilts to the size risk factor quite simply and effectively. In order to explore the impact of the suggested small cap bias, our investment research consultants regressed the monthly returns of the IMA UK All Companies series against the UK market, size and value risk factors. The result is graphically depicted in Figure 10.8. The IMA UK All Companies series had a statistically significant exposure to smaller size and a statistically insignificant exposure to the value risk factor. A simplistic proxy for the IMA UK All Companies series was created – which they named the IMA UK Passive Index Proxy – holding 71% exposure to the FTSE All-Share and 29% exposure to the DFA UK Small Cap Index. This places it in comparable market/size space to the actual IMA UK All Companies Index. They did not attempt to replicate the statistically insignificant weighting to growth stocks, which would have helped the active managers marginally, as value underperformed during this period.

Figure 10.8 Regression: IMA UK All Companies versus IMA UK Passive Index Proxy 2004–2013

Source: Albion Strategic.

The return of the IMA UK Passive Index Proxy, over the ten years to the end of 2013, was 9.93% versus 8.82% for the IMA UK All Companies series. This reveals a 1.1% performance advantage for the passive index proxy over active managers, thus flipping the conclusion of the previously mentioned Trustnet study on its head. Deducting 0.3% for passive costs still leaves a performance advantage of 0.8%. This 1.1% differential provides enough margin to have executed the strategy using the appallingly highly priced index tracker funds (ongoing charges of 1% p.a.) that the report refers to, while still keeping up with the active managers, whose return aggregate return cannot, in practice, be captured.

Looking forward, with single-digit-basis-point ongoing charges coming, and firms capable of delivering market-returns-less-a-few-basis-points already in the UK market, a passive approach looks like a highly effective way to execute an asset allocation strategy.

Strategic valuation measures

The price earnings (P/E) ratio is a standard stock market valuation measure which is calculated by dividing a company’s current share price by its per-share earnings. Earnings can be historic (last four quarters) or prospective (estimate of the next four quarters) or a mixture of the two (last two and next two quarters). The historical average P/E ratio depends on which stock market and time period are selected. The average P/E ratio for the S&P 500 index of leading US shares the past 100 years or so has been about 15, compared with 19 at the time of writing. However, it has been as low as 5.3 (December 1919) and as high as 123.79 (May 2009).25

The CAPE (cyclically adjusted price earnings) Index is an alternative stock market valuation measure devised by American economist and academic Robert Shiller, which calculates P/E ratios based on the past ten years of earnings to smooth out temporary fluctuations in profits caused by business cycles. Shiller’s contention is that the current CAPE P/E gives a strong indication of the investment returns from equities over the next ten years. When an index is trading on a high P/E ratio – the multiple an investor is willing to pay for each £1 in earnings – this appears to lead to lower, subsequent ten-year returns and vice versa. Figure 10.9 illustrates the CAPE Index for the S&P 500 from 1900 to 2013.

Shiller believes that the stock market becomes increasingly overvalued when it exceeds it long-term average P/E ratio (about 15 for the S&P) and better value when below it. His view, that market valuation levels matter, is at odds with the basic contention that markets are broadly efficient and current prices reflect all known information. Shiller’s critics suggest that higher P/E ratios merely reflect the market’s rationale forecast of high rates of earnings growth.

Historic analysis of the CAPE shows that it appears to predict the 1929 crash, the buying opportunity and subsequent high returns predicted by the low P/Es of the early 1980s, the 2000 tech crash and the fact that in 2007 the market was still ‘overvalued’. Although the CAPE Index stands at around 25 at the time of writing, suggesting that markets are overvalued, Shiller makes clear that CAPE is not a short-term market timing tool but a means of adjusting up or down the long-term allocation to equities, as he states in a 2013 interview with Business Insider.26 It’s worth mentioning that Shiller did predict the tech crash in 2000 and the housing crisis leading up to the credit crisis, based on his valuation indices, and his book, Irrational Exuberance, is a best-seller.

Figure 10.9 CAPE Index for the S&P500 1/1900 to 12/2013

Source: Data from Yale University, Department of Economics www.econ.yale.edu/~shiller/data/ie_data.xls

Jeremy Siegel,27 Professor of Finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, thinks the methodology for calculating the cyclically adjusted earnings may be overly pessimistic, where certain accounting practices introduced in the 1990s may understate true earnings, driving up the P/E ratio. Siegel gives the example of the requirement for companies to write down assets when they fall in value, but not to have to write back any growth in these assets until they are sold. In addition, as companies earn more from overseas subsidiaries and a higher proportion of earnings comes from technology in the US, which tends to have higher margins, companies have become much more profitable. For these reasons Siegel believes markets are not as overvalued as CAPE might suggest.

Based on the available evidence, the Shiller CAPE Index certainly seems to be a valid valuation tool. The question is whether it can be used by investors to improve long-term performance. As we have seen earlier, there is little evidence that actively managed balanced funds deliver any long-run outperformance despite access to a range of valuation methodologies, including CAPE.28

Markets seem to be broadly efficient at setting prices, but sometimes historically high valuations can continue for a long time. For example, according to Siegel, in the 22 years since 1990 (to the time of the article referenced earlier) the CAPE Index had been above the long-run average for all but nine months and thus broadly pessimistic about the return on equities. During the period January 1990 to December 2013 the S&P 500 Index has delivered an annualised nominal, total return of 9.3%. Underweighting equities would have had a significant negative impact on portfolio returns.

Any valuation measure is only as good as the inputs used, and the outcomes can be highly sensitive to changes in assumptions. Who knows, in the future companies might see even higher profits, greater opportunities and bigger markets for their goods and services. The internet didn’t exist 20 years ago, computer tablets didn’t exist 10 years ago and social networks were just getting going 5 years ago. Several academic studies have reviewed the efficacy of various market-valuation methodologies, including other P/E-related measures, and suggest that there is no sure-fire way of valuing markets effectively and profiting from it consistently.29

Changing the long-term asset allocation mix of an existing portfolio on the basis of the CAPE seems to be a risky approach. However, for a new portfolio funded from cash, once you’ve established your asset allocation strategy, you might want to drip feed your money into the portfolio over, say, 24 or 36 months, if the CAPE indicates valuations are at extreme levels. At least that way you don’t invest all your money at a market extreme but you still get invested and benefit from market returns in the long run. Periodic rebalancing of the portfolio provides some protection from market extremes and is a valuable part of a sensible, robust portfolio strategy, which we’ll discuss in Chapter 12.

Making a choice

Having looked at a range of the available evidence there are several key questions that you need to answer:

- Do you believe that an active manager can, after adjusting for risk factors such as the value and smaller companies premiums, beat the market after costs from skill?

- If a manager can show that they have demonstrated skill in the past that has caused outperformance of the market rather than exposure to risk factors, do you think they can do so consistently over time?

- How confident are you that you can predict which manager will have the skill to provide this outperformance?

- How will you manage the risk of style drift?

- How will you manage your emotions and make rational decisions if the manager is underperforming?

- What will you do if the manager leaves (and managers move around quite a lot)?

Just because a manager or economic forecaster has called things right in the past, it doesn’t mean that they will repeat this in the future and stock markets can be irrational longer than you can stay solvent.

My view is that an evidence-based strategy, using low-cost funds, should be your default investment approach unless you have a strong conviction that an active investment approach will be successful, you disbelieve the evidence, or you need to believe active investment management works.

‘Most investors, both institutional and individual, will find that the best way to own common stocks is through an index fund that charges minimal fees.’30

Warren Buffett, Chairman, Berkshire Hathaway Corporation

Diversification is the only free lunch (don’t put all your eggs in one basket). Because we don’t know which asset classes will produce the best return or the lowest risk at any given point in the future, by combining them in varying proportions we can avoid or reduce the probability of big losses and participate in the returns that markets do deliver.

1 Bogle, J. (2007) The Little Book of Common Sense Investing, John Wiley & Sons, pp. 98–99.

2 Fama, E.F. (1970) ‘Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work’, Journal of Finance, 25(2): 383–417; Fama, E.F. (1977) ‘Foundations of finance’, Journal of Finance, 32(3): 961–964.

3 Professor Thaler (2009) ‘The price is not always right’, Financial Times, 5 August.

4 Fama, E.F. (2009) ‘Fama on market efficiency in a volatile market’, Fama/French Forum, Dimensional Fund Advisors, 11 August, www.dimensional.com

5 Markowitz, H.M., Hebner, M.T. and Brunson, M.E. (2009) ‘Does portfolio theory work during financial crises?’ www.ifa.com/pdf/Does%20Portfolio%20Theory%20Work%20HMM%20mbedits%205-19-09.pdf

6 Gwilym, O., Secton, J. and Thomas, S. (2008) ‘Very long-term equity investment strategies’, The Journal of Investing, 17(2): 15–23.

7 The graph in Figure 10.4 documents bull and bear market periods in the FTSE All-Share Index from February 1955 to December 2012. The market cycles are identified in hindsight using historical cumulative monthly returns. Monthly index returns are total returns, which include reinvestment of dividends. All monthly observations are performed after the fact. A bear market is identified in hindsight when the market experiences a negative monthly return followed by a cumulative loss of at least 10%. The bear market ends at its low point, which is defined as the month of the greatest negative cumulative return before the reversal. A bull market is defined by data points not considered part of a bear market. The rising trend lines designate the bull markets occurring since 1955, while the falling trend lines document the bear markets. The bars that frame the trend lines help to describe the length and intensity of the gains and losses. The numbers above or below the bars indicate the duration (in months) and cumulative return percentage of the bull or bear market.

8 Jensen, M. (1968) ‘The performance of mutual funds in the period 1945–1964’, Journal of Finance, 23(2): 414.

9 Davis, J.L. (2001) ‘Mutual fund performance and manager style’, Financial Analysts’ Journal, 57(1): 19–27.

10 Lynch, P. (1993) Beating the Street, Simon & Schuster, p. 60.

11 Ang, A., Goetzmann, W.N. and Schaefer, S.M. (2009) ‘Evaluation of active management of the Norwegian Government Pension Fund – global’, Ministry of Finance, Norway, p. 65.

12 Westaway, P., Thomas, C.J., Philips, C. and Schlanger, T. (2013) ‘The case for index fund investors for UK investors’, Vanguard Research, April.

13 Philips, C., Schlanger, T. and Wimmer, B, (2013) ‘The active/passive decision in global bond funds’, Vanguard Research, November.

14 SPIVA® US Year-end Report 2013, available at http://us.spindices.com/resource-center/thought-leadership/spiva/

15 Miller, A. and Miller, G. (2012) ‘Promoting trust and transparency in the UK investment industry’, SCM Private, www.scmprivate.com

16 Layfield, L. and Stevenson, S. (2011) ‘Separating skill from luck in REIT mutual funds’, Working paper in Real Estate & Planning, 06/11, University of Reading, www.reading.ac.uk/REP/fulltxt/0611.pdf

17 Fama, E.F. and French, K.R. (2009) ‘Luck versus skill in the cross-section of mutual fund returns’, Tuck School of Business Working Paper No. 2009–56, Chicago Booth School of Business Research Paper and Journal of Finance, LXV(5): 1915–1947.

18 Surowiecki, J. (2005) The Wisdom of Crowds, Anchor.

19 Sharpe, W.F. (1991) ‘The arithmetic of active management’, Financial Analysts’ Journal, 47(1): 7–9.

20 Ellis, C. (2009) Winning the Loser’s Game: Timeless strategies for successful investing, McGraw-Hill.

21 Li, J. (2010) ‘When active management shines vs. passive: Examining real alpha in 5 full market cycles over the past 30 years’, FundQuest White paper.

22 Ibid, p. 2.

23 Ausden, J. (2014) ‘Active funds trounce passive funds over all time periods’, www.trustnet.com, 13 January.

24 https://personal.vanguard.com/us/funds/snapshot?FundId=0540&FundIntExt=INT

25 Shiller, R. (2006) Irrational Exuberance, 2nd edition, Crown Business.

26 Blodget, H. (2013) ‘SHILLER: Stocks are priced for (relatively) crappy returns’, 25 January, www.businessinsider.com/

27 Siegel, J. (2013) ‘Don’t put faith in Cape crusaders’, Financial Times, 19 August.

28 Bogle, J.C. (2007) The Little Book of Commonsense Investing, John Wiley & Sons.

29 One of the most extensive and highly regarded studies on this subject is by Welch, I. and Goyal, A.A. (2008) ‘A Comprehensive Look at the Empirical Performance of Equity Premium Prediction’, The Review of Financial Studies, 21(4), July, 1455–1508, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1211941

30 Chairman’s letter, Berkshire Hathaway 1996 annual report, www.berkshirehathaway.com