YOUNG PEOPLE AND MONEY

‘Continuous effort – not strength or intelligence – is the key to unlocking our potential.’

Winston Churchill

In this chapter I want to give an overview and some practical ideas on how to help young people become good at managing their own and possibly, in due course, family money. The issues discussed in this chapter are the product of what I have learned from working with clients over the past 25 years. They are not meant to be prescriptive but to give young people and their parents, grandparents and wider family a greater perspective on developing a healthy and effective relationship with money.

Despite the essential role that money plays in our lives and the serious challenges presented by increasing life expectancy, students graduating with more than £25,000 of debt, unaffordable housing and the subsequent austerity arising from the global credit crisis, recent research1 suggests that about two-thirds of young people have never received any formal education on personal financial planning. The same research found, however, that half of the young people surveyed said they find personal finance ‘interesting’ and:

- nearly all still visit their bank branch at least occasionally

- nearly three-quarters have never used mobile banking – and many of those are worried about security considerations

- many don’t really consider student debt to be debt at all – apparently, because it is taken directly from their gross pay

- most are virtuous – nearly two thirds pay off credit and store card debt within a month to avoid interest payments

- women generally tend to have lower savings than men and are less likely to take investment risks

- more than four in ten of those who contribute to a pension do not know what type of pension they have – money purchase, final salary, etc.

Another recent study2 into the attitudes of people aged between 20 and 29 found that they estimate their lifestyle in retirement will cost them about £42,000 per annum in today’s terms. Despite this, 37% cited their main priority being to save sufficient capital to fund a deposit on a house or flat, although worryingly 24% were not saving at all. A 2014 estimate3 suggests that those in the 16–24 age group save £95 per month (11% of their average income) and those in the 25–34 age group save £118 (about 8.5% of their average income).

Money values and beliefs

While we could debate the relative importance and influence that money has in society, the fact is that it is central to our existence and wellbeing. Much of our approach to dealing with money in general, and personal financial planning in particular, is learned from our parents, wider family and peers as we are growing up. This leads to a number of money styles, which we discussed in Chapter 2 and are summarised again in Figure 23.1.

Early influences in relation to money

When I first meet new clients, one of the questions I ask them is how money was handled in their family when they were growing up, because that gives me a good idea of the key influencing factors on their own money style and values. Examples of these influences include:

- which parent handled the family finances and the messages that they gave to their children about money

- whether money was tight or plentiful

- whether there was/is tension between parents about financial matters

- whether their parents struggled to fund their education

- if money was plentiful, whether this was created by their parents or inherited

- any financially related issues or events when they were growing up that are memorable

- the approach to pocket money, working and rewards in general

- the lifestyle that the family enjoyed – frugal, lavish or somewhere in between

- role models, mentors or other individuals beyond the immediate family (a teacher or parents of friends perhaps), who influenced their attitude to money

- the messages about money that they picked up from their peers

- the messages and influences that they picked up from the media as they were growing up.

Figure 23.1 Money styles

Source: Created from data in Hallowell, E. and Grace, W. (1989) What Are You Worth?: Coming to Terms with Your Feelings about Money, Weidenfield and Nicolson.

While these early influences do affect your financial ‘personality’, they do not necessarily define how a young person relates to money, nor how good they will be at managing their personal finances. A real challenge for parents and grandparents who have become financially successful and/or inherited meaningful wealth, and as a result have enjoyed a good standard of living, is how to avoid this demotivating and/or disincentivising their children or grandchildren as they become young adults. Made in Chelsea is a ‘reality’ television series that follows the lives of young people from wealthy families living in Chelsea in London. It is telling that of the dozen or so characters, only two have a regular job and the rest seem to spend their time meeting for coffee and planning their social lives.

When a young person has known a nice standard of living as they were growing up, has not had to do much in the way of work to earn money (or obtain a monthly allowance) and has made few (if any) sacrifices or experienced hardship, there is a real risk that they will not develop the resilience, purpose and sense of self-worth from ‘running their own race’. My experience is that teaching their children and young people the value of money comes through the application, by parents and/or grandparents, of a number of approaches including, but not limited to:

- showing restraint and modesty – for example, using public transport, flying economy class one way and business class the other, buying the young person an older first car and them using this for at least the first few years of driving

- continuing to work and/or be involved in business activity even though there may not be a financial need to do so, in order to demonstrate a work ethic

- matching what the young person earns from part-time, temporary or vocational work, or paying them an allowance based on unpaid voluntary work

- making charitable donations conditional on the young person also making a contribution from their own resources

- encouraging them to carry out fundraising activity to fund a trip to carry out voluntary work in a developing country

- providing a monthly allowance that is less than the young person needs, but topping this up with variable payments linked to additional agreed positive activity or outcomes

- talking about money in a positive way and stressing the importance of regular saving and making good long-term financial decisions

- expressing gratitude for the family’s financial success, wealth and standard of living and appreciating that not all people have the same financial capability and resources

- not giving children and young people everything they want, but giving them what they need

- giving the child or young person the cash amount of any savings in school fees that may arise from achieving a scholarship

- providing a small amount of capital to enable them to invest this as they see fit, but not for spending

- explaining key terms and concepts in an age-appropriate and engaging way, possibly using graphical examples, stories, analogies and real-life examples

- not making love and acceptance conditional or linked in any way to material and financial success

- expressing how important it is to not be motivated solely by financial and materialistic reward.

Passion and purpose

Having something that one is passionate about leads to a strong sense of purpose, which in turn provides the necessary motivation to pursue those ideals and dreams. This is particularly important where financial incentives are not strong (or even non-existent) because wealth already exists in the family. Psychologists advise that a strong sense of purpose is essential for individuals to build a sense of self-worth, identity and character. It is also essential to enable a young person to define themselves without reference to their family’s financial status (whether poor, affluent or wealthy).

For example, my family was poor, we lived in a tiny house and we never had very much in the way of comforts. However, I never accepted that that was how I was going to live when I grew up. While clearly I had an economic incentive to work hard to improve my lifestyle, many of my peers who also lived in poor households seemed to resign themselves to the same fate as their parents and accepted that being poor and having limited choice was their destiny. One of my childhood friends did, however, live in a very large house, with extensive grounds, tennis courts, horses and a swimming pool, and his parents were clearly wealthy. Unfortunately he was a lazy, spoilt and greedy individual who, I believe, went on to cause a trail of upset, destruction and drama when he became an adult. Clearly, the financial success of his parents didn’t make him either a nice person or financially capable.

It’s not where you’ve come from that matters but where you’re going.

Human capital

Developing a sense of identity from having a passion and purpose can help young people to decide on the direction they want to take their life. Human capital is our ability to generate wealth and other positive outcomes from our own endeavours. Regardless of whether a young person starts out with any inherited wealth, they do start out with potentially a very high amount of human capital.

Many people consider a good education to be a stable foundation for happiness and success. Education means different things to different people. Some see it as a means to develop a love of learning in the broadest sense; some see it in terms of acquiring intellectual skills, knowledge and academic capability to enable the pursuit of a profession; while others see it as a means of developing social skills and taking part in character-building experiences. For many people a good education involves all of these elements.

It is common for first-generation successful people to want to give their children a better formal education than they had themselves. Parents who went to an independent school and/or went to university are, understandably, often keen for their children to do the same. Whether this leads to better financial outcomes for those young people is debatable, particularly if the things they are learning do not equip them to make good financial decisions, or be able to cope with adversity, or develop a vision and purpose for which they have a passion and some flair.

Parents often have strong ideas of what is right for their children’s future and how they should best develop their talents. For many young people, university will be a rewarding and enriching experience that helps them to develop their character, skills and independence. For others, whether or not they do well at school, sometimes university is not right for them, regardless of what aspirations their parents might have for them or the fact that they can afford to support them financially.

Basic literacy and numeracy skills are a prerequisite for anyone. However, many of the most well-known entrepreneurs, such as Bill Gates, Richard Branson and Steve Jobs, either dropped out of or never attended higher education, but went on to build multi-billion-pound businesses.

‘Press on. Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men with talent. Genius will not; the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent.’

Ray Kroc built McDonald’s into the most successful fast-food company in the world

Higher education funding

Higher education funding in England changed quite significantly in 2012/13. As a result universities are now permitted to charge students much higher tuition fees. A summary of the new funding system is set out in Table 23.1. Scottish and EU (excluding those from England, Wales and Northern Ireland) students studying in Scotland do not pay tuition fees, nor do they pay any form of graduate tax. While students in Northern Ireland have to pay tuition fees, these are a much lower fixed amount (£3,685 p.a. at the time of writing) for courses taken at Northern Irish universities.

The key changes under the new system are as follows:

- As in the past, students are entitled to take out a government-backed loan, which they do not have to repay until after graduation. However, students requiring loans must now borrow substantially larger amounts to meet higher tuition fees.

- Under both old and new systems, graduates must repay 9% of their gross income above a certain level of annual income. This threshold was £15,795 (in 2012 prices) under the pre 2012/13 system and this threshold increased in line with the RPI. The 2012/13 + threshold is higher (£21,000 in 2016 prices) and rises in line with average weekly earnings (which tend to rise faster than prices). Graduates must make repayments either until they repay their loan in full or until 30 years has elapsed (it was 25 years under the old system), after which any remaining debt is written off.

- Under the new system, graduates are charged a real (above-inflation) interest rate of 3% while studying and 0–3% after graduation (compared with interest equal to inflation as measured by the RPI – i.e. 0% interest in real terms), depending on their income.

Table 23.1 Higher education funding system in England for students first enrolled in 2012/13

| Students first enrolled in 2012/13 | |

| Tuition fees | Up to £9,000 |

| Fee loans | All students may get a loan from the Student Loans Company (SLC) to pay the fees and must repay SLC after they graduate. |

| Maintenance grant | In 2012, £3,250 if household income less than or equal to £25,000 p.a. Tapered away at around 18% withdrawal rate thereafter. No grant available when parental income exceeds £42,600. The maximum grant increases slightly in subsequent years. |

| Maintenance loan | The maximum loan is £4,375 for students living at home, £5,500 for others outside London, and £7,675 for those away from home and in London. The maximum loan is lower for the final year of study. Students lose 50p maintenance loan for every £1 they receive as maintenance grant. The loan is tapered away at 10% for household income above £42,875. All students are guaranteed at least 65% of the maximum loan. The parameters did not change in cash terms between 2012 and 2013. |

| Other student support | The National Scholarship Programme (NSP) was introduced to give at least £3,000 each to low-income students. Eligibility requires household income to be no more than £25,000. The award may be given as fee waivers. Universities determine the detailed criteria. Not all eligible students are guaranteed an award. The NSP has since been abolished for undergraduates. |

| Accumulation and repayment of student loans | |

| Real interest rate (relative to RPI). | |

| During study | 3%. |

| After graduation | 0–3% depending on graduate income: 0% if below the repayment threshold, linearly increasing to 3% for income at or above the higher repayment threshold. |

| Repayment rate | 9%. |

| Repayment threshold | £21,000 in 2016 (above which 9% of income is to be paid). |

| Higher repayment threshold | £41,000 in 2016 (at which point the real interest rate is 3%). |

| Threshold indexation | Annually in line with national average earnings from 2017. |

| Repayment period | 30 years. |

Source: Payback Time? Student Debt and Loan Repayments: What Will the 2012 Reforms Mean for Graduates?, Institute for Fiscal Studies, April 2014. http://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/7165

The combination of threshold and interest changes makes the system more generous in some respects and less generous in others. Recent research4 into the financial implications of the new English higher education funding system has drawn some interesting conclusions:

- Students will graduate with much higher debts than before, averaging more than £44,000, compared with about £25,000 under the old system.

- The lowest earners will actually pay back less than under the old system, whereas the highest earners will pay back much more.

- Only 5% of students will have repaid their student loans by the time they are 40 compared with about 50% under the old system.

- About 75% of all students will not earn enough to repay their loans within the first 30 years, leaving an average debt of £30,000 to be written off by the state.

For a graduate employee with earnings of more than £21,000 p.a. (in 2016 terms), the combination of tax, National Insurance contributions and student loan repayment means a combined marginal rate of 41% (20% + 12% +9%) until they hit real higher-rate tax (currently 40%), when the marginal rate rises to 51% (40% + 2% + 9%). That is not a pleasant prospect, especially as the research analysis referred to earlier suggests that it will cover most of the family-raising period. Yet repaying the loan early could mean in about three-quarters of cases removing the benefit of the 30-year loan write-off. For most families, rather than funding to meet student loan costs, the idea should be to fund to meet graduate living costs.

Many universities in other European countries offer similar courses taught in English, but charge much lower tuition fees than English universities. This cost saving needs to be weighed against the potential higher living and travelling costs and the quality of the degree obtained.

Learning about business

Where a family runs a business, regardless of whether the young family member goes on to higher education, it offers the potential for younger family members to gain work experience. Learning to communicate, collaborate and understand other people are key life skills that will serve any young person well in the future. Where there is an aspiration to pass on the family business to the younger generation, this will enable them to gain a good understanding of and appreciation for the business’s fundamentals.

I learned the principles of hard work, getting on with people, good organisation and delivering good customer service from working in the public house that my parents managed when I was a teenager. I didn’t always agree with my parents’ way of running the business, but at least I was in an environment where I could learn whether or not running a business was for me. Those early experiences laid the foundation for the skills that I developed later on when I started my own business – Bloomsbury – in 1998 and which I continue to lead to this day.

Financial capability

Financial capability refers to the basic skills we all need to make wise choices about money. Without these basic skills, the odds of having good financial outcomes are greatly reduced due to poor decision making and the higher likelihood of financial services organisations exploiting their customers’ lack of financial capability.5 In this section I set out the main basic financial planning concepts and offer some rules of thumb and practical principles and practices for managing money.

Budgeting

In the course of my career I have met many high-earning and wealthy people and in the early years I assumed that a high earner would become wealthy and a wealthy person would be able to stay wealthy. However, I learned that if someone spends more than they (or their wealth) earns, they will never become (or stay) wealthy. Learning to spend less than you earn, possibly by deferring certain spending, using cheaper alternatives, or earning higher income through increased work, involves more effort than having what you want whenever you want it. This is particularly the case if you always had a nice lifestyle as you were growing up and never had to make sacrifices.

Budgeting is one of the key skills to learn early on and is the foundation upon which financial freedom, choice, security and independence are based. Look at the range of monthly savings required to accumulate £1 million shown in Figure 23.2. At 5% p.a. investment returns and a ten-year time horizon it requires monthly savings of £6,600, compared with over the 30-year time horizon which requires £1,300 p.m. at the same rate of return. This is the classic trade-off that we all have to make each day between consumption now and deferring gratification to the future.

Figure 23.2 Approximate monthly contribution to build £1 million

Compound interest

‘Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world. He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.’

Albert Einstein

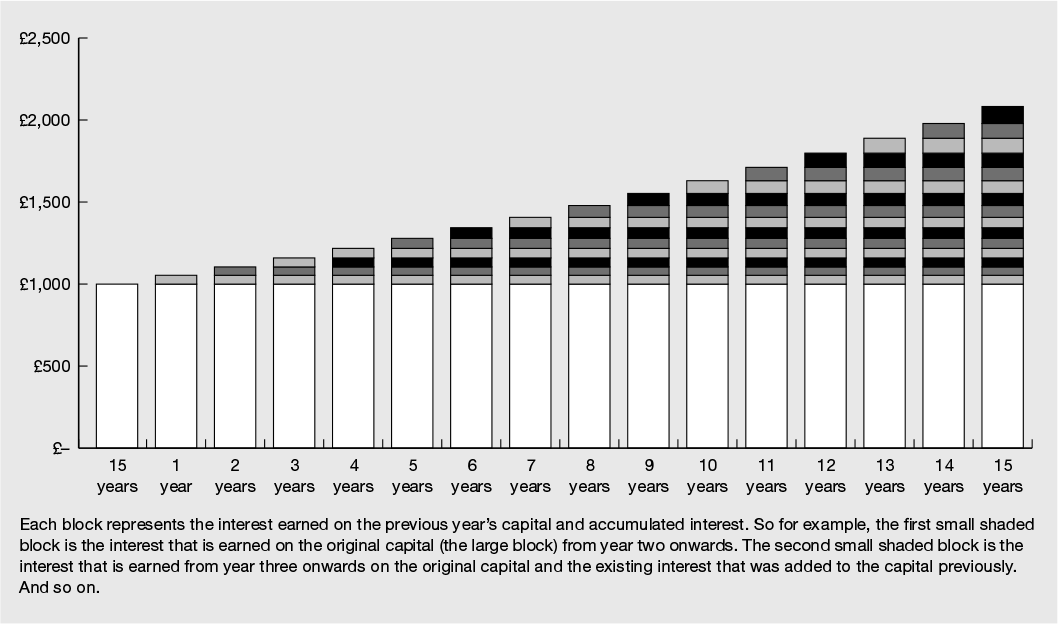

When we earn interest or other investment income and retain this with the principal capital, it is available to earn further income. Earning interest (or returns) on interest is a fundamental financial planning concept, which is illustrated in Figure 23.3. The higher the rate of return achieved and the longer the time horizon, the greater the effect this compounding will have, as illustrated in Figure 23.4.

Figure 23.3 Compounding works best over the long term

The Rule of 72

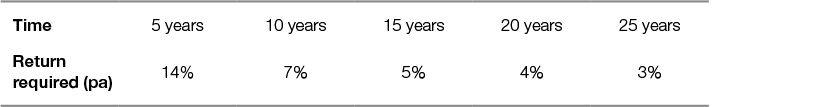

A really simple but highly useful and quick rule of thumb for working out compound investment returns, without having to do complicated calculations, is called the ‘Rule of 72’.6 If you take the compound (geometric) rate of return and divide it into 72, you can estimate the number of years it will take for you to double your money, as illustrated in Table 23.2. For example, 72/7 is about 10, so with 7% p.a. investment returns it would take roughly 10 years for capital to double. The higher the return, the less time it takes. The rule can also be used to estimate the annualised return required to double the value of money over a given time period, by dividing the time period into 72, as illustrated in Table 23.3.

Figure 23.4 How compounding works

Table 23.3 Rate of return to double your money over a specified time horizon

Inflation and the Rule of 72

The price of goods and services can stay the same, fall or rise from year to year. The most common position is that the price of the majority of goods and services will tend to rise over the long term. This rise, known as positive inflation, is measured by ongoing monitoring of the prices of a broad range of goods and services. Thus the inflation rate refers to the average rise in that basket of prices over the previous 12 months.

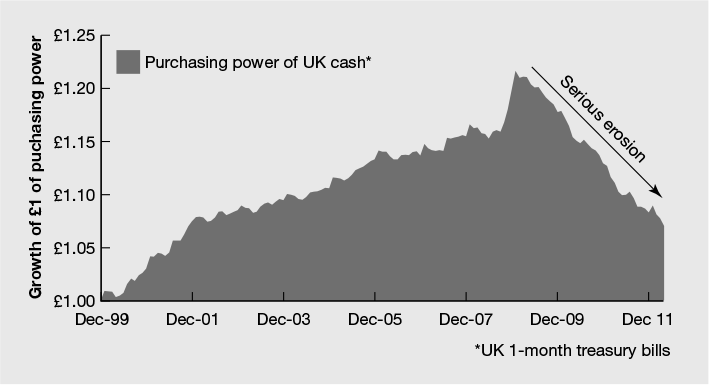

Because the impact of inflation is felt most acutely over the long term, it is a particular threat to savings that are accumulated or earmarked to fund lifestyle in older age when one can’t, or no longer wishes to, work. Even low rates of inflation can have a devastating effect on the purchasing power of money and the Rule of 72 can also be used to understand this, as illustrated in Table 23.4.

If we take a look at the longer-term historical returns that different investment asset classes have delivered, such as equities (owning a part share in a company), bonds and cash (lending to governments and companies), the mantra that comes to mind is ‘get (or stay) rich slowly’. Attempting to ‘get rich (or richer) quick’ is no different to gambling. Over the past 114 years cash has delivered a return of around 0.80% p.a. above inflation, government bonds around 1.2% p.a. and UK equities a shade over 5% p.a.7 Figure 23.5 illustrates the significant fall in the purchasing power of cash over the past 15 years.

Figure 23.5 Cash is not a good long-term investment strategy for long-term goals

Source: Albion Strategic.

Borrowing

Compounding also works in reverse where one borrows money and pays interest. The longer the time horizon and the higher the interest rate, the more total interest will be paid. Perhaps the best example of this is a repayment mortgage. Figure 23.6 shows a typical 25-year mortgage. Initially, the majority of the repayments relate to interest arising, with the balance being part-repayment of the loan. The loan does not reduce much in the first few years but then starts to reduce as compounding works in reverse. Clearly, the lower the interest rate charged and/or the higher the monthly repayments, the faster the loan will be repaid. It’s very easy to think that small percentages don’t matter but, as the example shows, this can amount to a significant cost over the life of a mortgage.

Figure 23.6 Repaying a mortgage with a 5% pa interest rate

Another example of the effect of compounding on debt is a credit card. A credit card offers a convenient means of buying goods and services and as long as the balance is repaid in full each month, there is no charge (although some cards do impose a small fixed annual fee for the card facility). To the extent that there is any outstanding balance each month, after deducting any partial repayment made, the card issuer will charge a relatively high rate of interest on the outstanding balance. The credit card company is keen for its customers to repay only the minimum amount necessary to meet the monthly interest costs arising, and this is typically set at 3% of the outstanding balance each month. Figure 23.7 shows how long it would take to clear a credit card debt with a typical 20% annual interest charge assuming different repayment levels.

Figure 23.7 Time to repay a £1,000 credit card balance with a 20% pa interest

Principles and practices

The following principles and practices are a simple summary of what I have learned from many other financially successful people, researching and studying what works and from my own experience of managing money.

Principles

Watch your spending

It doesn’t matter how much you earn. If you spend all, or more than, you earn, you’ll always be poor. While it is easy to be seduced into buying what you want, rather than what you need, deferring gratification and living within your means is the cornerstone of financial success. It’s a good idea to track your spending for a week or a month to get an idea where your money goes. Small but regular changes in expenditure can free up cash that you can use to build financial security. As the old saying goes: ‘Fools work for money and money works for the rich.’

Pay yourself first

Your financial security is the most important priority when it comes to devising a personal expenditure budget, before rent, travel, socialising, etc. I don’t mean that you should live like a pauper in pursuit of saving for the dim and distant future but rather change your mindset so that you prioritise regular saving as the first expense that you need to meet. It’s a bit like fitness training: start small to begin with and gradually increase the amount you save.

The devil of debt

Debt can be used responsibly to enable you to buy things today that you really need, such as a home in which to live, but for which you don’t have enough money to afford to buy outright (particularly if it is likely to appreciate in value). Whatever the reasons for which you borrow money, remember two things: interest is a definite regular cost that will reduce your ability to save and the capital must eventually be repaid.

While current interest rates are low, they won’t stay like that for ever and you need to think carefully about the impact on your expenditure if interest rates were, say, three times higher than at present (as they have been in the past). For this reason, even though buying a home with a mortgage can be a good long-term use of funds, make sure that you don’t overstretch yourself. There’s more to life than paying a mortgage. Also, avoid at all costs any form of borrowing on credit/store card or payday loans.

Keep it simple stupid (KISS)

The technology company Apple has made a virtue out of simplicity and it drives everything it does. You should adopt the same mindset in your personal financial planning and keep things as simple as possible.

If it looks too good …

If anyone tells you that they have a sure-bet investment that is virtually risk-free and will generate a 20% p.a. return, and it looks as though they actually mean or believe what they are saying, you need to give them a wide berth. If it looks too good to be true then it probably is.

Talking tax

You need to avoid becoming obsessed about avoiding tax. There is a whole industry dedicated to feeding off the greed and stupidity of people who hate paying tax and the authorities are increasingly attacking contrived and aggressive planning. You need to have achieved a degree of financial success to pay tax in the first place. In addition, a certain amount of tax is necessary for any decent society to operate in a fair and equitable manner. Minimise your tax bill by using all the legitimate and tried and tested products and solutions available, but not to such an extent that you don’t have enough money to live on today.

The media is not your friend

The media, in the form of newspapers, 24-hour news, websites or magazines, is not designed to help you to make good decisions. It focuses on what personal finance professionals call ‘noise’ or ‘financial pornography’ in the form of negative stories or sensationalist ‘get rich quick’ ideas because they are newsworthy. People who participate in such media comment are chosen because they make the media outlet more marketable, not because of their insight. In general, the news is not the truth but a form of entertainment, so remember that when forming your opinions about money.

Keep costs low and diversify

As a general rule with long-term investing you get everything that you don’t pay for. There is no evidence to support the commonly voiced (usually by those with an interest in the outcome) assertion that it is better to buy an expensive investment fund than a similar lower-cost one. Costs are certain whereas investment returns aren’t.

Practices

Build a cash reserve

Having a cash reserve available is essential to enable you to cope with the inevitable ups and downs that arise in life. Your cash reserve should represent at least three months’ expenditure, plus any funds that you will need to spend within the next few years, such as a house deposit or education/training costs. A cash ISA will usually offer better interest than standard savings accounts and is free of income tax, but avoid accounts that lock you in to a fixed term or charge a high transfer fee. You need to be able to access your cash should the need arise.

Protect your income

At the beginning of your working life your greatest asset is your ability to earn an income. If you were unable to work due to disability or illness for the medium to long term, it could consign you to poverty for life. Income-protection insurance will keep paying you a proportion of your income until you can return to work or reach a certain age (usually when you expect to retire). Healthy young people can usually get this type of cover easily and at relatively low cost, so if your employer doesn’t offer cover (as most don’t), buy your own personal policy. Do not confuse this with the (justifiably) much-maligned ‘payment protection insurance’, which pays out (if it does at all) for a short period only and does not provide any long-term protection.

Invest in yourself

In addition to a positive mental attitude, increasing your relevant skills and knowledge is the best way to increase your earning power. Therefore, looking for ways to invest in your capability, whether that’s night school, distance learning or day release by your employer, makes a lot of sense.

Join a pension plan

If you are offered the chance to join an employer-sponsored pension plan, then do so. Over the next few years (the exact dates depend on the size of the employer) all employees will be automatically enrolled in a pension plan through their employer unless they actively opt out. Whatever you do, do not opt out because the employer has to make contributions in addition to your own and the taxman also contributes. If you are self-employed, contribute to a low-cost pension with a choice of index funds and limit your risk by spreading your contributions across global markets, whether via one fund or several. The earliest contributions make the most growth and can make the difference between a decent retirement income or not. Although these funds can’t be accessed until age 55, that might actually be a good thing.

Don’t rush to buy property

Although buying your own home generally makes more sense than renting over the long term, avoid rushing in to buy a house until you have established your earning power, know where you want to live (which may be dictated by your work) and have a clearer idea of who, if anyone, will be your life partner. Buying and selling properties is an expensive business and if you have to sell at a time when the value of the property has fallen and your equity is reduced, it can set you back years.

Repay debt

An interest-free loan from your family is the cheapest form of borrowing and payday loans are the most expensive. As a general rule you should avoid, or repay, debt as fast as possible, starting with the most expensive debt first.

Below is a simplified list of borrowing types in broad order of interest costs, with most expensive first. Typical annual interest rates are shown in brackets:

- Pay day loans/doorstep lending (400–2,000%)

- Pawnbrokers (130–500%)

- Storecard (20–35%)

- Credit card (8–55%)

- Secured personal loan (6–23%)

- Unsecured personal loan (5–15%)

- Residential mortgage – 95% of property value (6%)

- Residential mortgage – 85% of property value (5%)

- Residential mortgage – 70% of property value (3%)

- Student loan – pre-2012 graduates (1.5%)

- Borrowing from family (nil to 4%)

Invest most of your long-term money in equities and property

Assuming you have followed all the suggested actions above, you should invest the bulk of any surplus income, plus your pension fund, into worldwide equities. A rough rule of thumb is to take your age from 100 and the answer is the amount to invest in equities. Don’t worry about volatility (the value moving up and down) because, with an asset class which is expected to rise over the long term (20 years +), regular savings benefit from something called pound cost averaging. This means that the average price you pay for the investments should be less than their average price over time. As you get older you may need to reduce your exposure to equities, but by then the compounding of returns (earning returns on previous returns) over time will have worked its magic and reduced the relative risk of price fluctuations because your capital should be worth many times what you invested.

1 Robson, S. (2012) ‘GENERATION Y: the (modern) world of personal finance’, July.

2 MRM London (2014) ‘Generation austerity’, January.

3 NS&I’s Quarterly Savings Survey, April 2014.

4 Payback Time? Student Debt and Loan Repayments: What Will the 2012 Reforms Mean for Graduates?, Institute for Fiscal Studies, April 2014.

5 The UK financial services regulatory structure, which is recognised as one of the most comprehensive and stringent in the world, has developed over the past 25 years or so in large part because there is usually an asymmetrical (opposing) relationship between the knowledge, understanding and financial skills of financial services firms and that of their customers. Without strict regulations and oversight, history shows that some firms are likely to exploit their superior knowledge, to the detriment of their customers.

6 The ‘Rule of 72’ is only a reasonable approximation.

7 Barclays Equity Gilt Study, 2014.