FINANCIAL PERSONALITY AND BEHAVIOUR

‘Information is not knowledge. Knowledge is not wisdom.’

Frank Zappa

With the internet, information is widely available at the click of a button and you could be forgiven for thinking that making good financial decisions should be easy. It is possible to go online and compare financial products, buy investment funds or insurance and apply for a mortgage or a loan. What is rarely considered is both the context in which those decisions are made and the psychology of the person making them.

Understanding your financial personality and how this influences your decision making is the key to living the life you really want and to developing and sticking with a financial plan that will help to ensure that money enables you to be true to that ideal. Your financial personality is your unique combination of natural ‘hard-wired’ and learned behaviours. Your behavioural characteristics will have a big impact on how you see the world, process information and react to messages from your family, friends and colleagues. If you are employing a professional financial adviser, it can mean the difference between a successful long-term relationship or not.

Your financial personality is made up of a number of interrelated elements, which include:

- your life goals, aspirations and motivations (which we discussed in Chapter 1)

- your financial risk profile

- your natural ‘hardwired’ behaviour, which is instinctive

- your learned behaviour – education, upbringing, environment, career and life experiences

- your ‘money style’

- your need for information and facts – how you like to receive this

- your planning propensity

- your level of emotional intelligence.

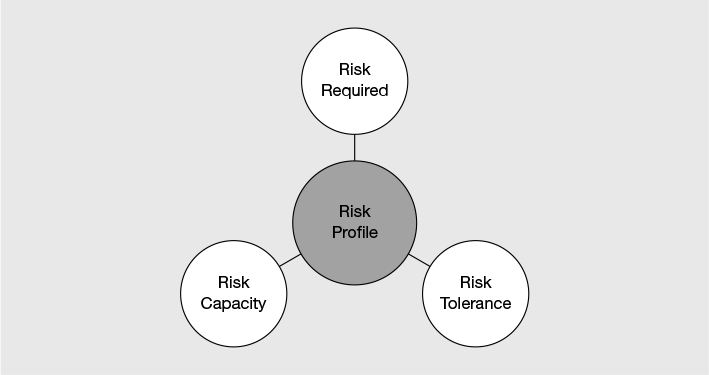

Financial risk profile

Knowing your personal financial risk profile is probably one of the most important aspects of making committed life and financial decisions. We all have a unique risk profile which is determined by our core and learned personality traits and our financial need to take, financial capacity to withstand and emotional tolerance to accept financial risks, as set out in Figure 2.1. By ‘risk’ I mean that there is a degree of uncertainty about what the actual outcome will be and, in the case of investments, their value will vary, sometimes extremely so. However, the payoff for that uncertainty is the probability that the overall long-term return will be higher than that provided by the no-risk investment and thereby enable you to achieve and maintain financial independence and other life goals which have a financial implication. The key principle is that higher risk is the source of higher returns.

Figure 2.1 The three pillars of risk

Source: Finametrica.

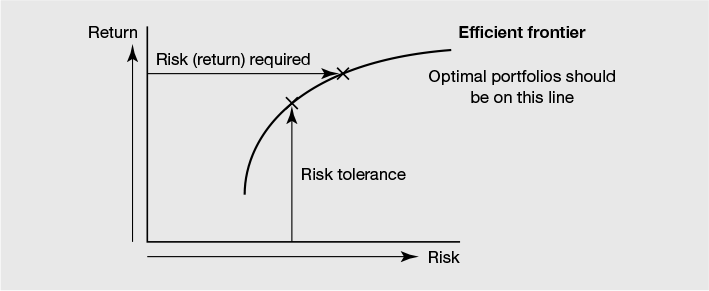

In Chapter 1, I explained that the starting point with your financial plan is to identify and quantify clear life goals and objectives. Once you know what you are trying to achieve you need to determine whether your goals are achievable by investing only in no-risk assets such as cash and equivalents. If the plan requires a higher return than that available from risk-free assets and you can’t find more resources or spend less, then you will need to invest some of your wealth into risky assets. Thus you have established your financial need to take risk (see Figure 2.2). A required return of just inflation could be achieved through investment in new-issue index-linked gilts and some cash, whereas a required return of 3% per annum over inflation would require a significant exposure to real assets such as equities and property.

Figure 2.2 Need for risk and reward

Your ability to withstand, financially, the effect of a permanent loss of capital and/or future returns being less favourable than anticipated is called risk capacity. This represents your ability to live with the consequences of an adverse outcome (whether permanent loss of capital or lower investment returns) and the impact that this would have on your lifestyle and other goals, given your financial resources and human capital. If you have significant income-earning potential from employment/self-employment and/or you have most of your post-working lifestyle expenditure covered by a government-backed defined-benefit pension scheme, then you can withstand significant loss of capital and/or volatility in your investment portfolio.

A different, but very important, measure of risk is risk tolerance. Unlike required risk (to meet the required return) and risk capacity, which are both financial parameters, risk tolerance is a psychological parameter, which represents your emotional ability to cope with investment uncertainty or loss. In other words, risk tolerance identifies how you feel emotionally about investment risk, and is based on a combination of your ‘core’ personality traits (inherent) and those learned (evolved) from life experience, education and environment. Some academics believe that risk tolerance profiles are largely settled by early adulthood, although they concede that risk tolerance decreases slowly over time and, as with other aspects of personality, may be changed by life events, but is otherwise stable.1 Having used psychometric assessments in my own firm for more than a decade, our experience is that with a majority of our clients we have seen their risk tolerance actually increase over the years. Clearly, there will be an upper limit to such increases, but the fact remains that for some reason their tolerance has increased and this is at odds with some of the academic analysis. It may well be that in working with us, our clients approach their wealth in a more structured and less emotive way, and together with continued education and appropriate support and guidance, they develop more understanding of why they are investing and do not react to news and other ‘noise’.

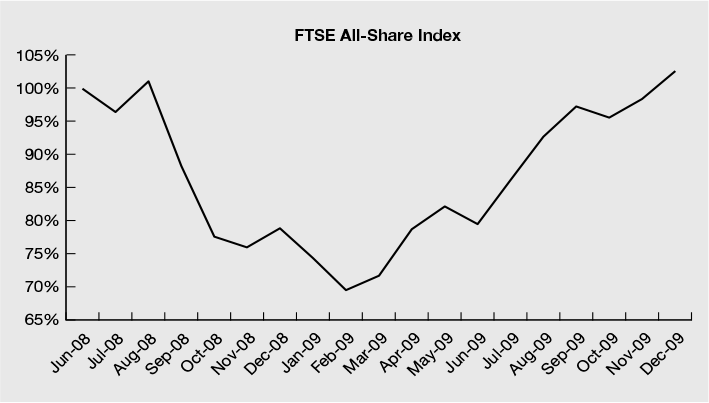

Figure 2.3 shows the UK stock market over the period of the global financial crisis. While the market recovered to its pre-crisis level within a few years, the fall in value in the interval was severe and happening against a relentless barrage of media messages of ‘This time it’s different’ or ‘Markets in meltdown’. This is where emotions have such a wealth-destroying influence, because if you bail out of equity investments when the market has experienced a temporary fall, you make it a permanent loss, from which you’ll almost certainly never recover.

Some people compartmentalise their financial affairs into mental accounts and think differently about each account. For example, imagine you have three portfolios: one for an emergencies fund, one for children’s education and one for retirement. If you have a mental accounting mindset, you are likely to place different levels of importance on these three portfolios and the (emotional) value to you of a £1 loss (or gain) may differ from one portfolio to the others.

The time horizon of each goal might be a key influencing factor as to whether or not you wish to view each goal in a different way in terms of risk tolerance, perhaps having a much lower risk portfolio for goals with a shorter time horizon than those that might be a few decades away. The question then arises as to whether you combine the weighted risk exposure of each portfolio to determine the overall risk exposure.

For example, imagine that you have a risk tolerance consistent with a 50% equities portfolio and you have two portfolios – a £100,000 medium-term portfolio for education expenses that is invested 30% in equities and a £200,000 portfolio for retirement expenses. If you are prepared to think of the two portfolios as a whole then the total allocated to equities would need to be £150,000 (50% of £300,000). As there is £30,000 in equities in the medium-term portfolio, £120,000 in equities in the retirement portfolio would bring the overall equities allocation to 50%, but the retirement portfolio would be 60% equities.

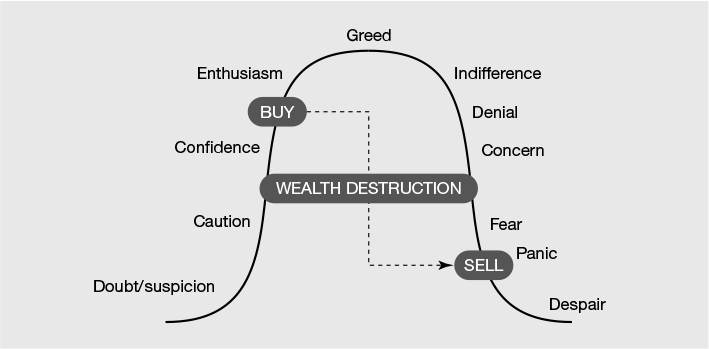

Risk perception can and does change depending on current experiences and events. You will usually have a higher investment risk perception when the stock market or property values are rising strongly and the world seems full of optimism and you feel wealthy. It can also vary depending on the type of investment or whether you are under pressure or stress.

When investment and property markets and the economy were booming, and before the global credit crunch hit, it was highly likely that your inherent risk tolerance traits were hidden. As we know, when the tide comes in, all boats rise! But what happened when the stock market dived or some other big negative event happened (the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait, 9/11, the global credit crisis, etc.) and your portfolio showed a large loss? The decision-making patterns for many of us can change radically when the good times turn to bad. This happens because when we are under pressure, our natural instincts instantly take over and for most of us we have little control over this: it just happens. This is why we often see a high degree of emotional decision making. This is not rational in the area of investing and it can cost investors dearly.

Tony Robbins, the US success guru, made a very good point when he said that we often overestimate what we can achieve in a year but underestimate what we can achieve in a lifetime. The same can be said of managing wealth in general and managing investments in particular. We get upset, annoyed or concerned if we don’t make a decent return in three or four years because we had unreasonable expectations of what could be delivered over such a short term. However, we are pleasantly surprised when we realise that, for all its ups and downs, our pension fund has quietly delivered a return of 3% per annum over inflation over the past ten years at a time when our cash at the bank is yielding a negative real return after tax.

Understanding your risk profile will therefore help you to understand what portfolio you need and can cope with, both financially and emotionally. Where there is a mismatch between any or all of the three risk elements (as illustrated in Figure 2.4), you will need to reconcile these before deciding on the most suitable investment strategy. For example, you might have to lower your desired lifestyle annual spending in later life, defer the date at which you will become financially independent, work for longer to earn and save more, or accept that you are going to feel uncomfortable at certain times in the future when markets tumble.

Figure 2.4 Risk need and tolerance mismatch

Natural behaviour is instinctive, very stable and highly predictable over time and is the ingrained response that shapes how you respond to external factors and scenarios. At the most basic and extreme level, these responses are triggered by the amygdala in the back of your brain, which could be described as your ‘fight or flight’ decision box. Natural behaviour usually surfaces when a person is under pressure – whether positive or negative. This natural behaviour is often masked by learned behaviour and as such it can become ‘buried’ and less obvious over time.

Learned behaviours are those that are shaped by your life experiences, education, environment and previous financial successes and failures, and these create your attitudes, beliefs and values. Overall your personality is dynamic, but it is driven by ‘hardwired’ natural behaviour and then shaped by these learned behaviours. Understanding your behaviour factors and how these surface in a stress or striving scenario is key to sticking with a unique life plan and avoiding ‘noise’ and other bad decisions that can blow you off course from leading a full life.

Emotions and money

The world is made up of lots of different types of people, all with their own idiosyncrasies and traits, experiences and preferences. The thing common to all human beings, however, is that, to a greater or lesser extent, most decisions, including those involving money, are made at an emotional level (see Figure 2.5). In his excellent book on investor psychology, Jason Zweig makes two important points: ‘Emotions overwhelm reason’ and ‘Financial losses are processed in the same area of the brain that responds to mortal danger.’2

Figure 2.5 Emotions and investing

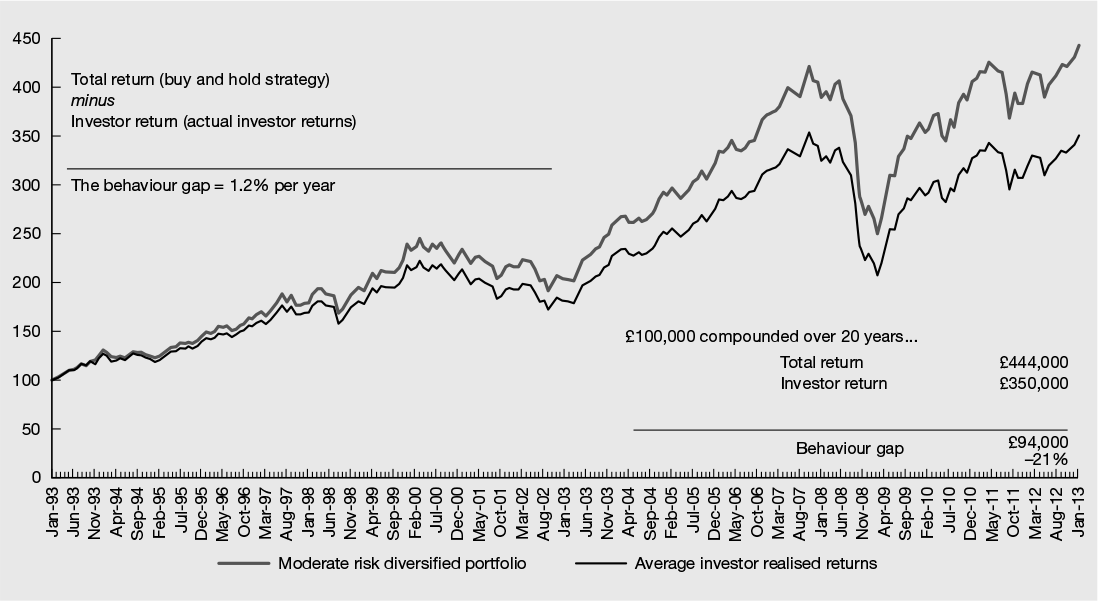

When emotions lead to bad financial decisions, this can result in complete loss of capital at one extreme (speculative investments) or lower investment returns than would otherwise have been available – known as the behaviour or performance gap. One analysis of UK investors showed that the performance gap was as much as 2.43% p.a. for UK smaller companies funds and 2.06% p.a. for growth funds.3 A more recent UK study4 found that:

‘On average the investment timing decisions of retail investors with regard to equity mutual funds has cost them performance of just under 1.2% per year over the eighteen year period of our study. Although 1.2% may not sound very high, compounded over 18 years it represents a cumulated under performance of 20%, compared with a simple buy and hold strategy.’

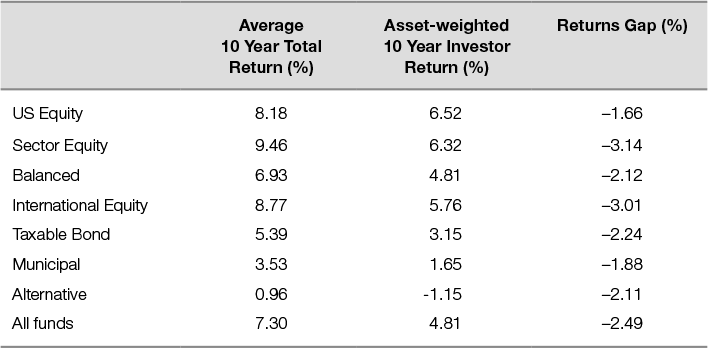

It has been estimated5 that the true cost to the average investor in forgone long-term returns, due to their inability to make rational decisions in the short term, is 2–3% per year, with the cost for many being even higher. This contention seems to be supported by recent analysis carried out by Morningstar, the investment fund information provider. In its 2014 review of US investors, it found that the behaviour gap to the end of 2013 was 2.49% p.a., up from 0.95% ten years ago.6 Table 2.1 shows the performance gap for major fund sectors.

However, even using an annualised return gap of ‘just’ 1.2% p.a., a £1 million portfolio invested over 20 years would have translated into £940,000 in lost returns (see Figure 2.6) for the average investor, purely as a result of bad decision making.

Because emotions play such a large part in our financial decision making, having a great education or a high intellect is no guarantee of financial success or happiness. Sure, all other things being equal it is preferable to be well educated and to have a good intellect, but it isn’t enough for financial happiness and success. That’s why history is full of examples of people with high intellect, natural ability or inherited wealth, who died lonely, unhappy and penniless.

Figure 2.6 The long-term impact of the behaviour gap

Source: Barclays Wealth, ‘Overcoming the cost of being human (or, the pursuit of anxiety-adjusted returns)’, March 2013.

Table 2.1 Morningstar behaviour gap results

Source: Kinnel, R. (2014) ‘Mind the gap 2014,’ Morningstar. http://news.morningstar.com/arti-clenet/article.aspx?id=637022

Behavourial finance is the study of human psychology as it relates to money. Over the years academics have identified a number of common behavioural factors that influence how we make financial decisions. The following are the most widely understood behavioural factors.

Over-confidence

People think that they make better financial and investing decisions than they really do. It’s similar to how most people think that they are above-average drivers. We tend to be over-optimistic when investment markets have risen and over-pessimistic when they have fallen. This is the opposite of what you need to do to have a good investment experience.

Extrapolation

People often base their financial decisions too heavily on recent events, or they give more weight to facts that support their beliefs and opinions, assuming that recent returns (good or bad) will continue in the future.

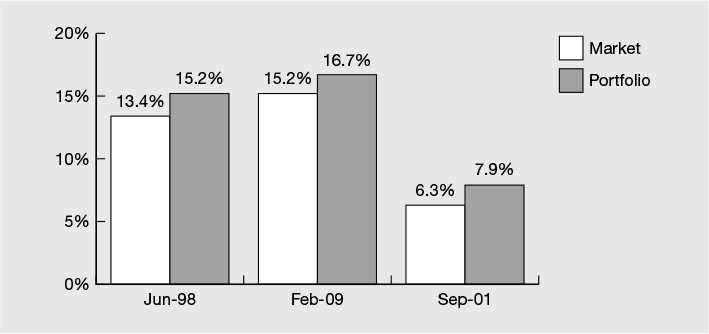

A good example of over-confidence and extrapolation was a survey of about 1,000 individual investors, on three separate occasions between 1998 and 2001 (see Figure 2.7). Participants were asked to give their predictions for how much they thought the stock market and their own investment portfolio would rise over the next 12 months. On two of the occasions, when the stock market had experienced a strong rise, investors’ predictions for the rise in the stock market were bullish and for their own portfolios were even higher. On the occasion when the stock market had experienced a significant fall, investors’ expectations for the stock market performance in the next year and for their own portfolios were about half of what they had been on the two previous occasions.

Figure 2.7 Over optimism, extrapolation and investor predictions

Source: Data from Fisher, K.L. and Statman, M. (2002) ‘Bubble expectations’, Journal of Wealth Management, 5(2), 17–22.

Hindsight bias

As the saying goes, hindsight is a wonderful thing. After the event, things seem obvious and we wonder why we didn’t see them coming. ‘How could I have been so stupid?’ Hindsight bias therefore lulls us into thinking that it is easy to predict the future.

Familiarity bias

Investing in what you know gives a false sense of control and lower risk perception, compared with investing in things that are less familiar. This bias typically arises when an investor has a legacy shareholding arising from an inheritance or previous employment, and leads to an overconcentration of risk which is not compensated by way of higher returns. Someone once told me that the stock market does not reward investors with risk premiums for ‘loyalty’ or ‘familiarity’.

Regret avoidance

This trait relates to the concept of ‘once bitten, twice shy’, in that when we have experienced the pain of losing money, we try to avoid the behaviour that caused it. We kid ourselves that we have learned from our mistakes, which leads us to avoid, for example, technology after the tech wreck in 2001, or the stock market as a whole after the heavy falls during the global financial crisis of 2008, even though we know that big market falls are followed by rapid market recoveries. Having a structured plan and a disciplined approach to decision making helps minimise such wealth-destroying behaviour.

Self-attribution bias

We like to take the credit for when things go right and blame other influences or factors when they go wrong. There is always a pundit who was so clever and smart that they made the right call on the direction of investment markets, interest rates, the price of oil, etc. because they could see what others didn’t see or chose to ignore. Investors in Apple or even Facebook now say, ‘Look how smart I am’, whereas when Enron went bust investors said, ‘No one could see that coming!’

Money styles

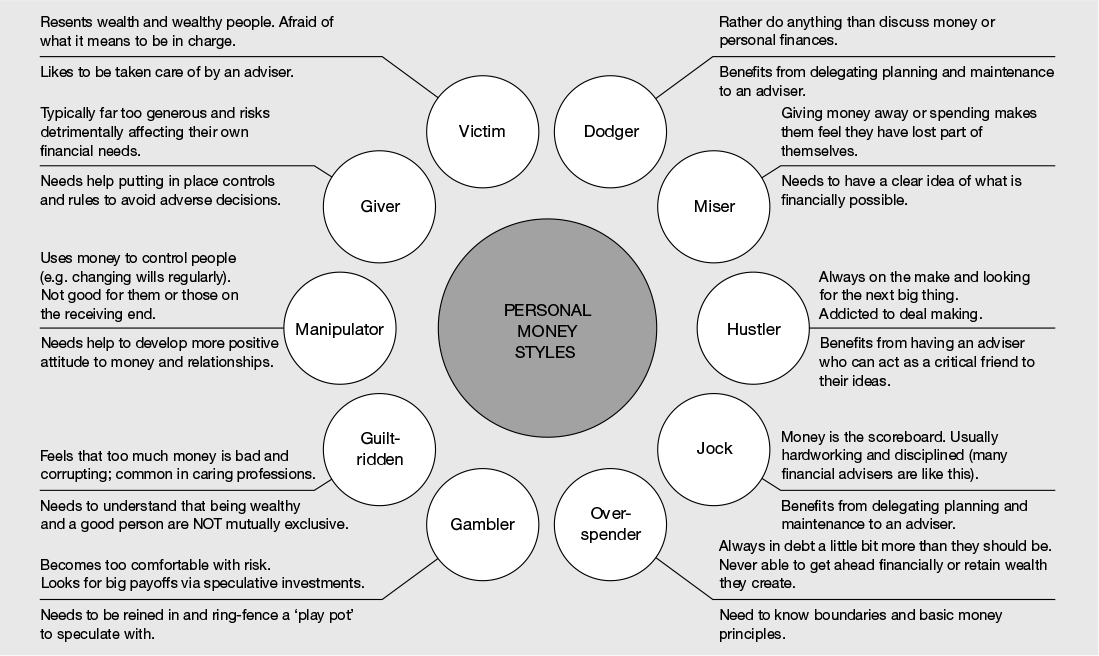

Money means different things to different people, although the core meaning and emotional connections relate to self-worth, love, security, power and attractiveness. If you have a greater understanding of the link between your emotions, financial habits and practices, as well as of the role that money plays in your family, you can become emotionally healthier. This should lead you to make better financial decisions and feel much happier and more content.

Money styles represent the core emotional motivations in relation to money (see Figure 2.8). These broad descriptions should help you to work out which is your primary style and what this means to your financial happiness. In my case I most associate with the ‘Jock’ money style because I relate to the attributes of that style of being hardworking, disciplined and responsible and using money to enable me to have fun and variety in my life. However, I am less inclined to the attribute of seeing money as a scorecard, because I realised many years ago that no amount of wealth would ever make me feel wealthy, so I don’t define my happiness or success in terms of my net worth. I have to admit, however, that I feel much happier having accumulated wealth than when I had nothing.

Figure 2.8 Money styles

Source: Data from Hallowell, E. and Grace, W. (1989) What Are You Worth?: Coming to terms with your feelings about money, Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Communication style

Are you a ‘big picture’ person or someone who likes lots of detailed information? A ‘big picture’ person will not want to wade through a long, detailed report, whereas a ‘detail’ person will be anxious if they don’t have in-depth information to enable them to make key decisions. Someone who is fast-paced and likes lots of variety and minimal information will not appreciate a long, slow and detailed lecture that labours over facts. Yet a reserved, reflective and slower-paced person will love this approach. Your core communication style also extends to the form in which you like to express yourself and how you prefer to have others communicate with you. To find out your preferred communication style you can visit www.financialdna.com and take the free Communication DNA Profile.

Planning propensity

Your financial personality includes your propensity and need to manage your personal finances and wealth or to engage the services of a professional. Once you have worked out which one you are, you can determine the type of advice and service that you need and from which you would derive good value for money. In simple terms you will be either a

- ‘do-it-yourselfer’ or a

- ‘collaborator’ or a

- ‘delegator’.

Do-it-yourselfer

As the name suggests, this type of person has a strong need for control and will seek lots of information; they typically have an above-average intellect. They will enjoy spending time on financial matters and be very well organised. They rarely benefit from collaborating or delegating to others as they do not value their time more than the cost of the collaboration/delegation. If you are in this group then the only time you are likely to want, need or value professional advice is to help with a specific situation or a one-off, more complicated situation. Examples include complex property transactions; selling a business; setting up a family trust; structuring a sophisticated tax wrapper for a large portfolio; or selecting and arranging a tax-driven investment solution that is available only from authorised financial advisers.

Collaborator

This type of person is similar to a DIYer but usually lacks the confidence to make financial decisions on their own and will usually seek advice and assistance from professional advisers, salespeople and organisations like the Citizens’ Advice Bureau, the Pensions Advisory Service or the Money Advice Service. They will also usually seek access to information from magazines, newspapers, websites, books (like this one) and friends and other contacts.

If you a collaborator then you may value and benefit from some form of periodic advice and services, but it will be important that this is not more extensive and expensive than you want or need. It is common for a collaborator to engage a ‘full-service’ advisory service, which is aimed more at those clients who are looking to delegate rather than collaborate. If you are willing and able to take more responsibility for your wealth and carry out some of the day-to-day aspects yourself, then you will probably save yourself money and become more confident about your financial decisions if you choose products and services that are less extensive and as a result less expensive than a full-service offering.

Delegator

This type of person is keen to ‘outsource’ most day-to-day aspects of managing their wealth, although they will want to have close involvement in formulating strategy. Typically, but not in all cases, a delegator will have more complex financial affairs and higher levels of wealth. Looking at the big picture is usually enough for delegators, as they have better uses for their time. Delegators are usually the most financially successful people precisely because they have learned when and to whom to delegate for best effect. They rarely do something themselves that they could delegate to someone else.

If you are a delegator, who has complex and significant wealth and/or a high surplus income, then a full-service advisory firm will probably be the best choice, as you will be able to derive the maximum value for the fees. When the value of your time is very high, you have little inclination to learn about financial matters in detail and/or your needs are complex, the price of a good, fee-only wealth management service will often pay for itself many times over. We’ll discuss the role of guidance and advice in Chapter 4.

Emotional intelligence

Recent research into the human mind has found that the secret to success in any long-term endeavour, whether it is in business, relationships or investing, is an attribute called emotional intelligence (otherwise known as EQ). EQ is a type of intelligence that is significantly different from the standard IQ-based definition of ‘clever’ we’re all used to. The topic of EQ has received significant coverage in the business world in the past few years, fuelled in particular by Daniel Goleman’s books7 aimed at helping business people to use the skill to further their careers and effectiveness.

With Goleman’s model for EQ, the emotionally intelligent investor would, for instance, calmly make investment decisions based on a higher consciousness of who they are and with a positive personal relationship to money (the first facet, ‘self-awareness’). This is instead of making decisions based on an emotional impulse that sabotages their financial position. They also handle stress, disappointment and uncertainty more rationally and don’t allow those feelings or circumstances to control or initiate their decisions (the second facet, ‘self-management’).

Going further, the emotionally intelligent investor would also understand the emotions of others such as their partner, spouse or family members, recognising them and responding with empathy (the third facet, ‘social awareness’). Finally, a person with high investment EQ would have the ability to maintain quality relationships with others around them when making investment decisions, knowing how to motivate them effectively and appropriately and manage their money energy using subtlety, delicacy and tact (the fourth facet, ‘managing others’).

The role of EQ in investment has been little publicised, even though its application can be invaluable for investors. Whether this is because the investment process is seen as an objective, numbers-based, non-emotional process or the investment industry has simply not been made sufficiently aware of the existence of EQ is unclear. My experience is that a high level of EQ combined with sound financial knowledge, strategy and support can make the difference between a successful and a bad investment experience.

So why is understanding investment EQ so powerful? It is the ability to give a person enough confidence, focus and rationality to remain committed to their strategies even when the market value of their portfolio is declining, not living up to expectations or being superseded by other events.

Charles Ellis is one of the leading thinkers in investment management, the author of 6 books and 70 articles on investment and finance, and has taught the graduate school investment courses at both Yale and Harvard. He is a member of the Board of Directors of the Harvard Business School and a Trustee of Yale University where he also serves on the investment committee. Here’s what he had to say about emotions and investing and the key to a successful investment experience:

‘Principles that every investor should be thinking about… [that] investing is all about you, not about the market, about you and how you would feel most comfortable through thick and thin because there will be thick and there will be thin. There will be good times, there will be bad times and that’s part of life’s experience. And, you must be comfortable and candid about who you really are and what your investment capabilities are and what your emotional capabilities are so that you can set a pathway you can really stay with. Staying with it is the most important single principle.

‘Don’t be afraid of being candid about what your emotions are. Go ahead and accept who you are as a human being and if you can’t handle turbulence, don’t invest in turbulent securities. If you are more able to handle turbulence, take that chance because you can take it in your stride and invest that way. But, if you will aim at the right kind of investment mission and then stay with that mission you can have a winning experience and everybody in your family, everybody in your neighbourhood, everybody in the world can have a simultaneously winning experience if they each do what’s really right for them.’8

You are more likely to make rational decisions if you have a high level of self-awareness, financial education and experience, a secure relationship with money and a high level of ‘emotional intelligence’. Even then the instinctive aspects of your core personality will still have an impact on your financial decisions. With turbulent financial markets it is far more likely that your inherent risk tolerance will emerge and strongly influence your financial decisions.

At the end of the day you need to accept that there are some things you can control and some things you can’t and you need to have the wisdom to know the difference. In that context, knowing your life purpose and financial personality is likely to give you the best chance of making good financial decisions. Avoiding getting blown off course by the ‘noise’ from the media is difficult, but once you realise that their interests are not aligned with your own, you’ll start to focus on what really matters – staying disciplined in the face of adversity and extreme events.

1 Roszkowski, M.J. and Davey, G. (2010) ‘Risk perception and risk tolerance changes attributable to the 2008 economic crisis: a subtle but critical difference’, Journal of Financial Service Professionals, July. www.riskprofiling.com/Downloads/Risk_Perception_and_Risk_Tolerance_JFSP.pdf

2 Zweig, J. (2007) Your Money or Your Brain, Simon & Schuster.

3 Schneider, L. (2007) ‘Are UK fund investors achieving fund rates of return? An examination of the differences between UK fund returns and UK investors’ returns’, PhD Thesis, July.

4 Clare, A. and Motson, N. (2010) ‘Do UK retail investors buy at the top and sell at the bottom?’, Working paper, Centre for Asset Management Research, Cass Business School, September, p. 4.

5 Barclays (2013) ‘Overcoming the cost of being human (or, the pursuit of anxiety-adjusted returns)’, March, www.investmentphilosophy.com/uploads/cms/51f002473490d.pdf

6 Kinnel, R. (2014) ‘Mind the gap 2014’ Morningstar. http://news.morningstar.com/arti-clenet/article.aspx?id=637022

7 Goleman, D. (2005) Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ, Bantam Books.

8 Transcript of video interview with respected investment expert and author Charles Ellis on investment fundamentals: www.vanguard.co.uk/uk/portal/Library/interviews--video-ellis.jsp