WEALTH SUCCESSION

‘Enough so that they can do anything they want, but not enough that they can do nothing.’

John C. Bogle1

Wealth succession is all about ensuring that the right people and/or causes receive the right amount of your surplus wealth, at the right time, in the most tax-efficient manner. It is not about giving away all your money to avoid inheritance tax, although that may well be a legitimate concern. If you’ve done your strategic wealth planning properly then you should have a good idea of whether you have any surplus capital or income available in your lifetime. However, before you start thinking of giving away any of your wealth or nominating beneficiaries in your will, I suggest that you consider what really matters to you and the impact that any gift might have on the recipient.

You might have concerns that your gift could have a detrimental effect on the recipient or cause tension within the family. Sometimes giving young people large amounts of money can have a negative impact on their motivation and life choices and lead to unhappiness. Treating beneficiaries differently can also cause friction between family members and you’ll need to think through the implications carefully. Leaving any gifting until your death might not be the best approach if the beneficiaries are having a tough time now and a financial gift could have a positive impact on their life. The key is to strike the right balance between helping and hindering beneficiaries. See Chapter 23 for more insights into young people and money.

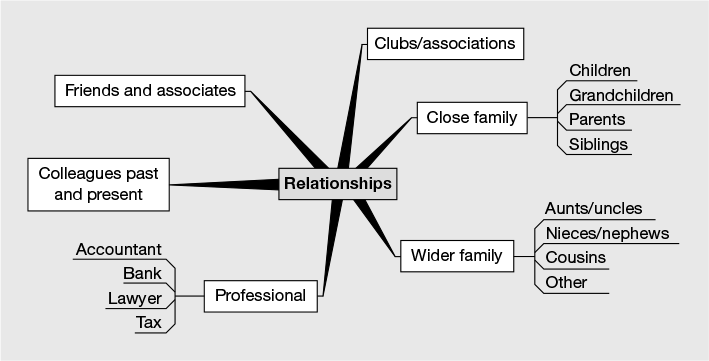

Some people are worried about their beneficiaries getting divorced and the gifted wealth disappearing in any subsequent financial settlement. In some cases your intended beneficiary might not want your gift and/or it might exacerbate their own IHT exposure. Significant wealth can also have a negative impact. You might find it helpful to draw up a family mindmap or organisational chart like the one shown in Figure 20.1, noting all relevant facts and issues so that you can discuss these with your professional advisers and agree a plan that avoids, as far as possible, any potential problems.

Figure 20.1 The family map

You might want to give directly to family members or a family trust during your lifetime and leave any charitable gifts to be made on your death, or vice versa. It is highly likely that one or more trusts would be required to help achieve your objectives. For many people, providing their children and grandchildren with a good education is an important priority, which is seen as a good ‘investment’. In some cases parents and grandparents view funding school fees as a more practical and positive method of transferring wealth to the next generation than giving them money either during their lifetime or on death.

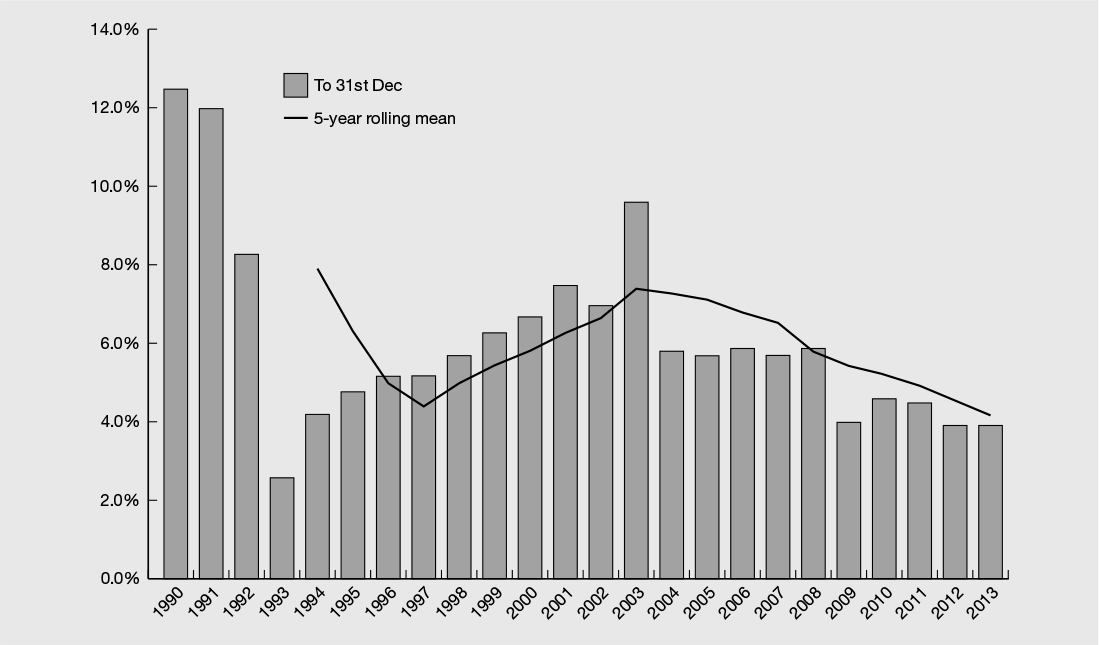

Funding a private education, however, is not an insignificant commitment and could well equate to more than £300,000 (about £250,000 in present-value terms) based on a cost of £5,000 per term. University fees and costs will add another £45,000 to that total cost. In addition, school fees inflation (see Figure 20.2) continues to be well above price inflation, with latest figures from the Independent Schools Council (ISC) showing this to be 3.9% in 2013.

Figure 20.2 UK school fees inflation 1999–2013

Source: Independent Schools Council.

Inheritance tax (IHT)

IHT is a tax levied on your estate when you die. According to recent research carried out by the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), the number of estates that will be liable to IHT will quadruple from 2.6% in 2009/10 to 10% in 2018/19.2 The tax charge is currently a flat 40% and applies to your worldwide assets if you are UK domiciled, regardless of residence.

If you are non-UK domiciled, IHT applies only on your UK assets, unless you have been UK-resident in 17 out of the past 20 years, when you will be ‘deemed’ UK domiciled and your worldwide assets potentially subject to UK IHT. The first £325,000 of your estate is effectively tax-free and this is known as the nil-rate band (NRB). Married couples may carry forward their deceased spouse’s unused NRB, with the amount expressed as a percentage of the available NRB exemption applicable at the time of the second death.

Carrying forward unused nil-rate IHT band

Andrew died in 2012, leaving £200,000 of his estate to a discretionary trust, which had a wide class of potential beneficiaries, including Andrew’s four adult children and his widow, Sandy. Andrew had never made any previous gifts other than those that were classed as immediately exempt from IHT. Because the nil-rate IHT band was £325,000 when Andrew died, his remaining unused NRB expressed as a percentage is 38.5% ((£325,000 – £200,000)/£325,000).

Sandy dies in 2020 when the IHT nil-rate band has been increased to £400,000. Therefore, as well as her own NRB of £400,000, Sandy’s executors may carry forward 38.5% of Andrew’s unused NRB, but based on the NRB at the time of Sandy’s death. Therefore, Sandy’s executors may carry forward £154,000 (£400,000 × 38.5%) of unused NRB from Andrew’s estate.

Any assets left to your surviving spouse or civil partner are also exempt from IHT as long as they are UK domiciled. If you are UK domiciled (or deemed to be) but your spouse or civil partner is non-UK domiciled, then the maximum amount you can leave them free of IHT is £325,000. A non-UK domiciled individual (or their legal personal representatives within two years of their death) who has a deceased UK-domiciled spouse/civil partner may make an irrevocable election to be treated as UK domiciled for IHT purposes only. This will retrospectively apply to the previous seven years. This election will cease to apply if the surviving spouse making the election ceases to be UK tax resident for at least four successive tax years after the election.

Certain assets are exempt from IHT and these include holdings in unquoted trading businesses (including assets used by such a business), agricultural land and buildings and commercial woodland (but not the land). Gifts to political parties and registered charities are exempt from IHT, whether made in your lifetime or upon your death. In addition, where at least 10% of your taxable estate is left to a registered charity, the tax on the rest of your estate is reduced by 10% to 36%. This isn’t sufficient to make your beneficiaries better off but it’s useful if you intend to leave some of your wealth to charity.

As a general rule, you can give away any amount of your estate during your lifetime to individuals or bare/absolute trusts and as long as you derive no use or benefit from the gifted amount and survive for at least seven years afterwards, the gift will fall out of your estate for IHT purposes. This type of gift is known as a potentially exempt transfer (PET). However, there are ways of making gifts that are immediately exempt from IHT and that allow you to retain some benefit without offending these requirements.

If you do not survive a PET by seven years, then the PET will fail (known as a failed PET) and thereby be subject to IHT to the extent that it exceeds the available NRB at the time of death. Any tax due will benefit from a reduction (known as taper relief) on a sliding scale from 20% to 80% if death occurs after the first three years (see Table 20.1). Any gift made to a non-bare/absolute trust in the seven years prior to a failed PET will be taken into account in determining whether and if so to what extent the NRB is available.

Table 20.1 IHT taper relief reductions

| Time between the date the gift was made and the date of death | Taper relief percentage applied to the tax due |

| 3 to 4 years | 20% |

| 4 to 5 years | 40% |

| 5 to 6 years | 60% |

| 6 to 7 years | 80% |

Source: HMRC.gov.uk

Example

A failed PET

Andrea, who has never been married, died four years and two months after making a PET of £250,000. She had also made a gift of £250,000 to a discretionary trust seven years before her death. She had always used her annual and small gift exemptions separately and none of her assets or gifts was an exempt asset. Disregarding her remaining estate value, this is how the IHT position would be calculated:

Step 1 – PET was within seven years of death so fails with value of £250,000.

Step 2 – there was a chargeable lifetime transfer (CLT) of £250,000 within seven years of the original PET so this must be deducted from the NRB at the date of death.

Step 3 – the available NRB at date of death is therefore £75,000 (£325,000 – £250,000).

Step 4 – the failed PET is reduced by the remaining £75,000 unused NRB, leaving £175,000 taxable.

Step 5 – IHT on failed PET is £70,000 (£175,000 × 40%).

Step 6 – taper relief of 40% applies because the PET failed within years 4–5.

Step 7 – the IHT payable is £42,000, being 60% of the normal amount, after deducting the 40% taper relief.

Gifts to most types of trusts (other than bare/absolute trusts) are known as chargeable lifetime transfers (CLTs) and, as such, attract an immediate tax charge of 20% of the amount of the gift over the available NRB and the annual exemption(s). However, if the gift to the trust, together with any other gifts made to the same or other trusts in the past seven years, is equal to or less than the NRB (currently £325,000), no immediate charge to IHT is due. In addition, no immediate charge to IHT will arise if the gift to the trust is:

- of business or agricultural assets that qualify for 100% relief, or

- funded from regular gifts made out of surplus income, or

- paid from a pension trust that itself meets the IHT exemption rules.

As long as you derive no use or benefit from the gifted amount and survive for at least seven years afterwards, the gift will fall out of your estate for IHT purposes and no further IHT will be payable. All growth arising from the date of the gift will arise outside your estate. For this reason it makes sense to gift as much as you can up to the maximum of the NRB, whether to an individual(s) or to a trust every seven years if you can afford to do so.

Estate planning basics

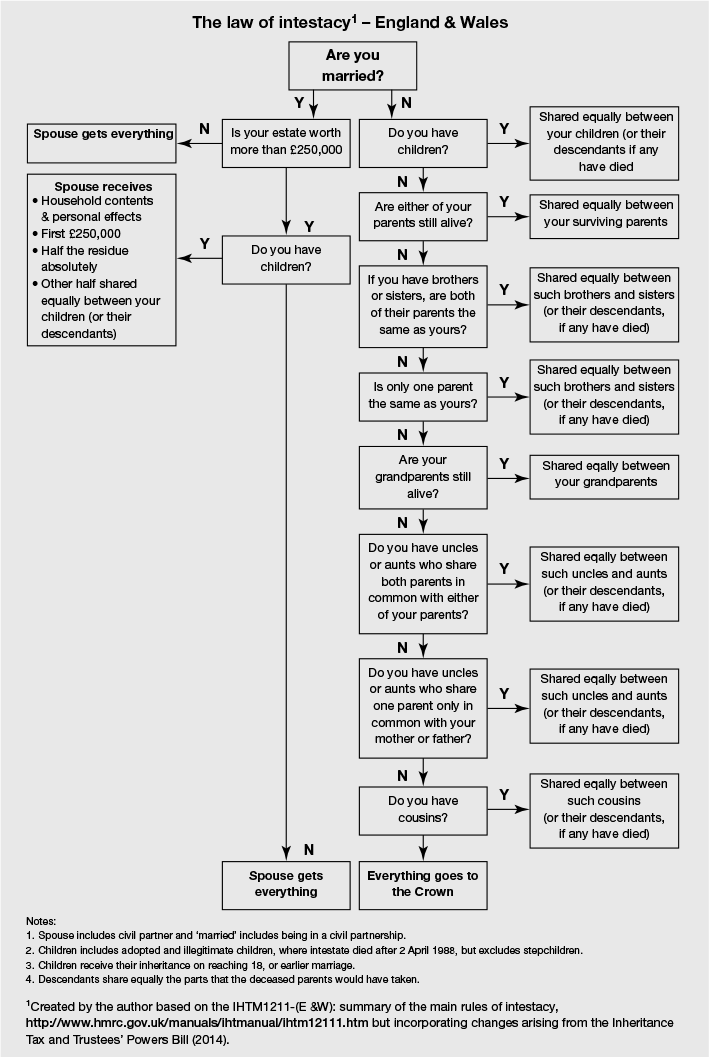

Having a valid will is essential to help others deal with your affairs following your death. If you don’t have a will in place when you die, you will die intestate. This means that your assets will be distributed in accordance with the rules of intestacy, which are set out in Figure 20.3. Depending on the amount of your wealth, the types of assets you own and the makeup of your family, dying intestate is unlikely to be recommended. For example, a spouse or civil partner is unlikely to inherit all your assets under the intestacy rules.

Although it is possible to effect a deed of variation to override the intestacy rules and vary the basis on which an estate is to be distributed, as it is with a will (more of which later), this relies on the various beneficiaries who are entitled to the inheritance all agreeing to the terms of any variation of intestacy. This is fine if everyone agrees but not if they don’t. Also, if there are any minor beneficiaries involved, the variation has to be approved by the court, which is obviously expensive and uncertain.

Ideally, you need to have a will in any country in which you own real property as some countries like France have forced heirship rules that are different to the rules in the UK. If you need a will in more than one country, you should take legal advice to ensure that these are coordinated.

I do not recommend using a will-writing company to draw up your will unless your affairs are simple and modest. Many of the will-writing companies use non-legally qualified representatives to take instructions and see to the signing of documents. This can lead to mistakes and misunderstandings that can turn out to be costly and problematic further down the line. In addition, some will-writing companies have no or very modest professional negligence insurance cover.

Figure 20.3 The law of intestacy – England and Wales

Source: Data sourced from ‘IHTM12111–Intestacy (E&W): summary of the main rules of intestacy’, available online at www.hmrc.gov.uk/manuals/ihtmanual/ihtm12111.htm

There are a number of ways that you can increase the tax efficiency and flexibility of your will to deal with things such as business assets, second marriages, unequal gifts of property or other assets. A good lawyer is worth paying for and, as long as they have a clear grasp of what you own and the overall context of your wealth strategy and personal objectives, they can help to craft a more sophisticated will that reflects your wishes and is tax-efficient. The more wealth you have and the more complex your financial affairs, the more important and valuable this will be.

Deed of variation

Where property is inherited, whether under a will, under the intestacy rules or by survivorship (i.e. it is owned as joint tenants), it is possible to redirect the inheritance to achieve an immediate IHT saving by using a deed of variation.

Ordinarily the inherited assets will accumulate in the taxable estate of the receiving beneficiary, who may not want or need the inheritance. Instead of choosing to make a gift of the inheritance (which would be treated as either a potentially exempt transfer or a chargeable lifetime transfer), it is possible for someone to take advantage of the deed of variation option and achieve an immediate inheritance tax saving on their own estate.

In order to achieve the desired outcome, the variation must:

- be in writing

- contain a statement that the relevant legislation (s. 142 IHTA 1984) is intended to apply

- be made within two years of the death of the donor,3 by the person(s) who would have benefited from the original gift.

In addition, the property must have been included in the deceased’s estate at the date of death.

In practice, there is no requirement to vary the entire amount of the inheritance, which could enable the recipient to choose to vary only part of it. It is possible to vary an amount directly to an individual or to a trust. The option chosen will depend on the beneficiary’s specific circumstances, of course, taking account of factors such as whether they are wealthy in their own right, whether they are likely to want to retain control and whether they may wish to benefit in future should the need arise.

A variation into a discretionary trust enables the original recipient to retain access by being named as a beneficiary. They can also maintain control by acting as one of the trustees. This is a viable planning option that does not fall foul of the gift with reservation provisions or pre-owned assets tax – the variation is effectively treated as having been made by the deceased for IHT purposes provided the necessary conditions are satisfied.

Note that in cases where the variation is into trust and the original recipient of the legacy is included as a beneficiary, they will be taxable on any income arising within the trust (under what are known as the settlor-interested trust provisions).

Life and pension policies

If you have life policies or pension plans, you should ensure that these are written under an appropriate trust so that they do not form part of your estate for IHT and to enable the proceeds to be paid out quickly, side-stepping the process of probate on the rest of your estate. However, you need to be careful when putting existing policies into a trust in case they are deemed to have a value and, as such, could trigger an immediate tax charge. Most term policies with no cash in value will not cause a tax problem on transfer as long as you are in good health at the time. Some investment-based policies, particularly whole-of-life types, could have a significant value. However, any life policy could be deemed to have a value equal to the life assurance benefit if, at the time of transfer to trust, you are suffering from a terminal illness of which you were aware.

Mortgage protection policy held in trust

A debt is deductible from an individual’s estate for IHT purposes only if it is repaid from the deceased’s estate. Therefore, where a life policy has been taken out to repay a mortgage in the event of the borrower’s death, but placed under trust for the benefit of relatives, those proceeds would not be available in the deceased’s estate to repay the loan. In cases where there are no other funds available to repay the outstanding mortgage from the estate, HMRC may refuse to allow the mortgage to be deducted from the estate for IHT purposes. The solution to this problem is for the trustees of the life policy to lend the funds to the deceased’s personal representatives, to meet the IHT liability that arises due to not being able to deduct the mortgage from the estate. This would mean that the estate passes to the beneficiaries encumbered with a new liability which would be IHT deductible in the future.

Although a trust will never fail because there is no trustee available to act, it is advisable to appoint at least two trustees other than yourself, so that there are no undue delays in distributing life policy proceeds to beneficiaries, if required. Your trustees should be people you trust to make good financial decisions and you should feel comfortable that they could deal with the trust’s business.

Death-in-service benefits from occupational pension schemes and personal pension plans written under a ‘master’ trust-type arrangement usually pay out at the discretion of the scheme’s trustees. However, you may complete a written nomination stating to whom you would like the trustees to consider paying out any lump sum death benefits. It is essential that you complete and keep up to date this nomination as it is the first thing that the trustees will refer to in the event of your death, although they will not be bound by it. Instead of nominating your spouse (or civil partner) or other beneficiaries as your preferred recipients, you might instead create and nominate a special trust known as a ‘pilot’ or ‘bypass’ trust to receive any death-in-service or pension plan death payment (see Figure 21.7 in Chapter 21). The benefit of doing this is that it enables the lump sum to be paid into the trust and avoids the capital falling into the estate of your chosen beneficiaries and thus avoids IHT being charged on that capital if any of your beneficiaries subsequently die. In addition, it will help avoid other potential creditors, including local authorities (care fees), ex-spouses or civil partners, or bankruptcy proceedings that may be experienced by your beneficiaries.

If, however, you have a personal or directors’ pension plan from which you have taken taxable withdrawals and/or a tax-free lump sum, the payment of the remaining fund to a bypass trust would cause a 55% tax charge. This can be avoided if there is a spouse/civil partner and/or financial dependants to whom taxable income benefits can continue to be paid.

Digital and virtual assets

The growth in social media and cloud-based digital storage systems means that increasingly, people need to leave clear instructions as to what should happen to these ‘digital assets’ after their death. The Law Society recommends that, at the very least, an up-to-date list of online accounts, such as email, banking, investments and social networking sites, should be kept. Not only will this save executors time and money, it will make it easier for family members to recover important or sentimental material – such as photographs on social networks – that might otherwise be lost.

The growing trend for digital media also means that many people will have amassed valuable assets in the form of music and films, internet domains, YouTube videos and even computer game characters in online games. Without proper records, much of this can be lost on the owner’s death.

While access to online accounts and other digital media could theoretically be provided by leaving details of passwords, access codes, etc. in a will, this is rarely a good idea. Not only does the will become a public document after death, this sort of information may change regularly, in which case successive codicils will be required to amend the will – leading to expense and inconvenience.

An online storage arrangement is potentially a good solution, but there are obvious risks with using this type of service as well. It may be that for the time being (or at least until the example set by Google – allowing users to specify which of their ‘trusted contacts’ can access their accounts after they die – is followed by other service providers), setting out express instructions in a Letter of Wishes will give the user the best chance of enabling their executors and loved ones to take the necessary steps to access and protect valuable digital content.

The licensing agreements attaching to some assets – such as iTunes and Kindle e-books – specify that the assets die with the original owner. However, as technology advances, wills may need to be reviewed to ensure that their provisions specifically cover the testator’s digital estate. A general legacy of personal items may not be wide enough to cover assets that exist virtually only and specific ‘digital asset’ legacies may therefore need to be developed to cover this.

The box gives a quick checklist of the main planning points worth considering in your estate plan that will help minimise IHT and avoid other claims on your estate.

Checklist

- Use your current annual gift exemption of £3,000 (the previous year can also be used if you have not already done so).

- Make annual gifts of £250 capital to any number of beneficiaries (no one person can receive more than £250 unless this is part of the £3,000 annual exemption and you cannot add together these exemptions to give £3,250 to one person).

- Make gifts in consideration of marriage (£5,000 for your own children, £2,500 for grandchildren, £1,000 to anyone else) if relevant.

- Make regular gifts out of surplus income (see the following section) to individuals or, if the amounts are meaningful, a discretionary trust, as the gifts fall out of your estate immediately.

- Lend capital to individuals or a trust to ‘freeze’ the value for IHT purposes.

- Gift capital or assets up to the value of the nil-rate exemption band to a trust to freeze the value of assets, avoid future growth arising within your estate and remove the gifted value from your estate after seven years (currently the limit is £325,000 every seven years).

- Invest in assets that qualify for business property relief or agricultural property relief (effective after two years of ownership) to avoid IHT on the value on death.

- Make gifts to charities or, if the amounts are significant and you have particular objectives, to your own charitable foundation to remove them from your estate immediately for IHT purposes.

- Effect a long-term insurance policy on your life in trust to pay out some or the entire IHT bill on your death (or the second of you to die if you are married or in a civil partnership).

Normal expenditure out of surplus income exemption

This is one of the most underused IHT exemptions but also one of the most effective and simplest to use. If you meet the conditions then the gifted amount falls out of your estate immediately and does not use up any of your nil-rate band. The conditions that must be satisfied are as follows:

- the gifted amount must form part of your usual expenditure

- it must be made out of income (whether or not it is taxable, but not income arising under a purchased life annuity)

- it must leave you with sufficient income to maintain your normal standard of living.

Using life insurance

If you have made a gift that is classed as a PET and might become taxable if you die within seven years of the gift, to the extent that it exceeds the available NRB on death, life insurance can provide the funds to enable the recipient of the gift (known as the donee) to meet the IHT that will become due. The NRB can also be used up for these purposes if you have made a gift to a trust (other than a bare trust) in the seven years prior to the PET. It is worth noting that responsibility to pay the tax due is in the following order:

- donor (or their personal representatives)

- donee

- anyone in whom the property is now vested

- any beneficiary of a trust who receives the asset in question.

If you still have a residual IHT liability and either can’t or don’t want to carry out other planning, and are in reasonable health, you (or your beneficiaries) could take out long-term life assurance for some or all of the tax liability to reduce the loss to your beneficiaries. The cost depends on your age, health and lifestyle factors. You should expect premiums to increase significantly once you reach age 75. The policy would need to be written under trust to avoid it forming part of your estate. Please refer to Chapter 13 for a fuller explanation of the role of life insurance in IHT planning.

Getting a bit more creative

There are numerous planning solutions that are usually (but not always) more complicated and costly than the standard planning referred to earlier. The benefits include quicker or higher IHT savings; being able to retain some use, enjoyment or benefit from the asset or capital; and/or greater flexibility in how and when wealth can be distributed to beneficiaries. The box shows a non-exhaustive list of some of the more widely used planning concepts, a number of which are explained in more detail in Chapters 21 and 22.

Some widely used planning concepts

- A discounted gift trust immediately removes a proportion of gifted capital from your estate while still allowing you to benefit from a preselected ‘income’ during your lifetime. As a general rule, the higher the amount of income and the lower your age, the greater the immediate discount.

- Use trusts to obtain IHT reductions on property, including your main home, second home and investment properties.

- Restructure businesses to maximise IHT exemptions, the main one of which is business property relief (BPR), which provides complete exemption from IHT once owned for two years.

- Loan capital on interest-free terms to a trust of which you are not a beneficiary in order to freeze the value of your capital for IHT purposes but allow yourself access to the capital through repayments of the loan on terms agreeable to you.

- Do gifting in the right order to minimise IHT. The general order should be: 1) set up any lifetime pilot trusts (to receive pension death benefits, etc.); 2) make loans to individuals or trusts; 3) gift exempt assets; 4) make chargeable lifetime transfers; 5) make potentially exempt transfers.

- Gift assets to a special type of ‘reversionary’ trust that allows you to remove assets from your estate while still benefiting from some or all of the gifted capital by way of a future ‘reversion’ of the gifted asset.

- For mixed-domiciled marriages/civil partnerships, investigate how you can exploit the UK-domicile election rule to allow IHT exemption.

- If you are non-UK-domiciled and have not been a UK resident for more than 17 out of the past 20 years, consider putting non-UK assets in an excluded property trust before you become deemed UK domiciled, to avoid UK IHT on those assets subsequently applying.

- Via your will, pass a minority interest in a property to a trust that benefits unconnected beneficiaries, i.e. not your spouse or civil partner, so as to create a discount of the value of the surviving spouse or civil partner’s retained share for IHT purposes.

- If you have a spouse or civil partner, create a nil-rate band trust on your death and have the trustees of your residual estate enter into a debt arrangement with the trustees of your NRB trust. With the passage of time during which your spouse or civil partner survives you, the debt has the effect of ‘sucking’ value out of their estate and placing it in the NRB trust.

- Borrow assets/capital from a trust interest-free and then gift those assets/capital to another trust so as to create a debt on your estate that reduces the value of your estate for IHT purposes, as long as you survive for seven years and the debt is actually repaid by your estate upon your death.

- Invest in assets, such as AIM shares, enterprise investment schemes and special inheritance tax investment services, which qualify for IHT exemption under BPR or agricultural property relief (APR) after two years.

- Leave any asset that qualifies for BPR/APR in a discretionary trust and have your surviving spouse/civil partner exchange an equivalent amount of their own assets for the BPR/APR assets so that they own IHT-exempt assets (after two years’ ownership) and the trust owns the assets that would have been subject to IHT.

The key point to bear in mind about some creative planning, particularly that which involves the family home or other property, is that there is always a risk the tax authorities may change the rules to render the planning ineffective retrospectively. Over the past ten years alone we have seen a barrage of anti-avoidance rules that has removed any tax benefit from thousands of ‘schemes’. In addition, new IHT planning ‘schemes’ are now included within the Disclosure of Tax Avoidance Scheme (DoTAS) rules that already apply to income and capital gains tax planning.

Ensuring that your financial affairs are well organised means that you will not leave a mess for your family to sort out if they have to deal with your financial affairs in the event of your death. Wealth succession planning can be as simple or complicated as you wish, but it must be viewed in the context of your own needs, values, resources and tax position. In any event, a decent private-client lawyer is essential to help you form a sensible wealth succession strategy that is in context with your financial needs and overall financial plan.

1 Bogle, J.C. (2010) Enough: True measures of money, business, and life, Wiley.

2 Institute for Fiscal Studies (2014) ‘Death to the death tax?’ April, available at www.ifs.org.uk/publications/7164

3 Donor means the deceased individual who leaves assets.