STATE AND PRIVATE PENSIONS

‘My dad loves what I do and I support my parents financially because they didn’t have a job that gave them a pension.’

Marilyn Manson, American musician, songwriter, actor, painter

There are two government-administered state pensions in the UK – the basic and additional state pensions.

Basic state pension

The basic state pension (BSP) is a taxable, flat-rate pension payable from state pension age (SPA) to anyone who has built up a sufficient number of qualifying years through payment of National Insurance contributions (or received National Insurance credits – NICs). The maximum (sometimes referred to as ‘full’) BSP for a single person in 2014/2015 is £113.15 per week.

People retiring between 6 April 2010 and 6 April 2016 must have 30 qualifying years for full entitlement to BSP. Entitlement is reduced by 1/30th for each qualifying year below 30. Qualifying years relate to National Insurance contributions (or credits) having been paid. People retiring from 6 April 2016 must have 35 qualifying years for full entitlement to BSP. Entitlement will be reduced by 1/35th for each qualifying year below 35.

Married couples (and civil partnership)

Where a spouse does not have sufficient qualifying years for a full BSP in their own right they can apply, on reaching SPA, for a BSP based on their spouse’s National Insurance record. The spouse with insufficient National Insurance will obtain 60% of the contributing spouse’s BSP (if the contributing spouse has a reduced BSP then it is 60% of the reduced rate). Since 6 April 2010 it has no longer been a requirement that the contributing spouse has claimed their BSP; they must just be eligible to do so for the spouse with insufficient qualifying years to claim theirs (e.g. a wife reaching SPA at 62 can make a claim based on her husband’s National Insurance record provided that he has also reached SPA, regardless of whether he is claiming or has deferred claiming BSP). Where a married woman has some qualifying years in her own right she can use her husband’s National Insurance record to increase her own BSP by the lesser of:

- the shortfall between her reduced-rate BSP and the full-rate BSP, and

- the amount of BSP her spouse’s record will provide.

This also applies to married men and civil partners, but only where their wife/civil partner was born after 6 April 1950.

State pension age (SPA)

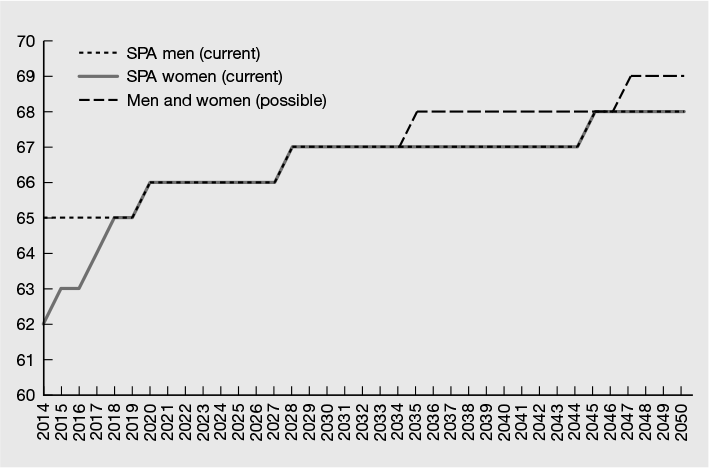

The state pension is not paid automatically at SPA, but must be claimed on or after reaching SPA. The SPA is currently 65 for men and is being raised gradually to 65 for women by December 2018. The SPA for both men and women will then be raised gradually until it is 66 by October 2020. At the time of writing (May 2014) it was announced that the SPA will be raised to 67 for men and women between 6 April 2026 and 2028. Figure 17.1 shows these changes graphically. If you have not reached SPA already you can check your SPA by visiting www.gov.uk/calculate-state-pension

It is interesting to note that in 1981 individuals received the state pension for 25% of their adult life but by 2000 this had increased to 30% and by 2010 it had risen to 33%. To keep the proportion of adult life in receipt of the state pension constant at the 2010 level (33%), the SPA would need to be 66.5 by 2030; at the 2000 level (30%) it would need to rise to 68 by 2030; and to get back to the 1981 level (25%) it would need to rise to 72 by 2030.1 This suggests that the current intention to raise the SPA to 68 between 2044 and 2046 is highly likely to be brought forward.

Annual increases

For those living in the European Economic Area, the BSP is increased every year by whichever is the highest of:

- the growth in average earnings

- the growth in prices

- or 2.5%.

For those living elsewhere, the BSP remains level and so will lose its purchasing value over time.

Deferring state pension

It is possible to defer taking your state pension, in which case it will be increased by a factor of 0.20% for each week of deferral, equivalent to 10.4% a year (with no compounding, unfortunately). This factor was last reviewed in April 2005 when the banks’ base rate was 4.75%, a figure closely matched by the yield on short-dated gilts, meaning that the deferral offer was attractive but not a great deal.

Since 2006 there has also been the option to defer the state pension in return for a lump sum and this is calculated on the basis of accumulating the pension payments not made (subject to this being at least 12 months of continuous deferment) at a gross interest rate of bank base rate + 2% (i.e. 2.5% at present). The lump sum is fully taxable but taxed at your marginal rate, not simply added to your income. This treatment means that basic-rate taxpayers can avoid a possible one-year trip into the higher-rate income tax band when they draw their state pension lump sum. It also protects against the loss of age allowance.

There are several factors that you need to take into account when considering whether to defer taking your state pension. Before I explain these, consider what the government minister in charge of pensions had to say about state pension deferment choices:

‘The way in which the deferral increments are worked out means that there is an extra percentage on the pension when it is drawn, while the way in which the lump sum is worked out is different and, bizarrely, relates to the Bank of England base rate. There are times when, if an actuary were making such a decision, the person should choose increments and there are other times, depending on interest rates, when the person should choose the lump sum.’

Steve Webb MP2

Deferral for an increased pension

This option now looks very appealing, particularly for shorter terms where the lack of compounding is of less import. For example, using figures from the DWP’s guide, deferring a £100 per week state pension for a year currently provides either:

- a taxable lump sum of £5,270, or

- an increase in taxable pension of £10.40 per week (£540.80 a year), possibly with a corresponding increase to any dependant’s pension.

For a person aged 66, that extra pension (on a single life basis) would cost about £15,0003 to buy on the open market. It is worth noting, too, that for the basic state pension, a ‘triple lock’ now applies to increases, i.e. the greater of 2.5%, CPI and average earnings increases. In theory this should have prompted the DWP to worsen the deferral terms. For other state pensions, CPI sets the increase basis, which arguably would require an adjustment in the opposite direction. Deferment will not suit everyone and if you are single you need to be aware that if you die while deferring state pension, your estate can benefit from only a maximum of three months’ unpaid pension.

The increase rate for deferring the state pension will be reduced from April 2016 to about half the current rate, which is still not a bad deal. Using a similar calculation to the earlier example, the new increment basis implies an extra £5.20 a week for each year’s deferral of £100 a week state pension. That extra £5.20 a week for a single person aged 66 (i.e. 65 + 1 year’s deferral) would cost about £7,6004 to buy on the open annuity market, assuming RPI linking, against a year’s pension forgone of £5,200.

Deferral for a lump sum

When the lump sum option was introduced in 2006, the Government Actuary’s Department calculated that deferral would be of financial benefit to the Treasury, which rather gives the game away. Finding more than a 2.5% gross return for savings is possible via cash ISAs, so the logical thing to do would be to draw the pension and use it to feed an appropriate savings account. This has the added benefit of avoiding some of the problems that deferral can create, e.g. where a wife has entitlement both in her own right and via her husband’s contributions and gains nothing from deferral.

There are two obvious situations where lump sum deferral is preferable to the draw-and-save approach:

- For someone whose total income is over £27,000, removing entitlement to the full age allowance, deferring state pension can produce a useful tax saving that more than compensates for the modest interest rate. For example, if £5,000 is taken out of the total income figure by pension deferral, this could result in an increase of up to £2,500 in allowances and thus up to a £500 tax saving – effectively a 10% net return.

- For someone whose income will fall into a lower tax band at some point after state pension age, the marginal rate tax treatment described above will normally make lump sum deferral more attractive. It might be possible to achieve this band shifting temporarily via carefully timed income withdrawals.

The lump sum deferment option is due to be abolished in April 2016.

Additional state pension

The additional state pension is an earnings-related pension, payable on top of the BSP, at SPA, where this is reached before 6 April 2016. Until April 2002, the additional state pension for employees was called the State Earnings-Related Pension Scheme (SERPS). The amount of SERPS pension you received was based on a combination of your NICs and how much you earned. In April 2002, SERPS was reformed and renamed the State Second Pension (S2P). It now gives a more generous additional state pension to low and moderate earners, certain carers and people with a long-term illness or disability. If you have joined an employer’s pension scheme you may have been ‘opted out’ of the additional state pension automatically. You can find out more from your scheme administrator or by obtaining a state pension forecast.

Additional state pension can arise from various state pension schemes, each with its own different and complicated set of calculations as to benefits payable:

- the Graduated Retirement Pension (GRP) – for earnings between 6 April 1961 and 5 April 1975

- SERPS – for earnings between 6 April 1978 and 5 April 20025

- S2P – for earnings since 6 April 2002.

Once in payment the additional state pension is increased in line with the RPI, but this is due to change from April 2016.

The Directgov website provides further information about basic and additional state pensions, and gives a quick estimate state pension profiler tool that calculates the BSP earned to date (see www.direct.gov.uk/en/Pensionsandretirementplanning/StatePension/DG_184319).

The basic and additional state pensions are dependent on an individual’s NICs and earnings over their working life. Additional state pension calculations are extremely complex and may be made up of a combination of GRP, SERPS and/or S2P. A comprehensive forecast based on an individual’s National Insurance record can be obtained from the Pension Service part of the Department for Work and Pensions (see www.direct.gov.uk/en/Pensionsandretirementplanning/StatePension/StatePensionforecast/DG_10014008).

Inheriting SERPS/S2P

The surviving spouse of a contributor to SERPS/S2P can, on the contributor’s death, inherit a percentage of their SERPS/S2P entitlement. For SERPS the maximum percentage payable is dependent on the date the contributor reaches SPA – for a contributor reaching SPA after 6 October 2010 the maximum SERPS their surviving spouse can inherit is 50%. For S2P the maximum amount is 50%.

Single-tier state pension

A new single-tier state pension will be introduced for those reaching SPA from April 2016. The pension will be set at a rate no less than the basic level of means-tested support (i.e. the Pension Credit guarantee credit, which is £148.35 per week for a single pensioner in 2014/15). It will replace entitlement to the BSP and additional state pension (including shared additional pension and graduated pension).

Other features of the new single-tier pension include:

- minimum period of National Insurance contributions to qualify for any benefit to be set at ten years

- maximum benefit requires 35 years of contributions (this compares with 30 years under the existing state pension)

- entitlement will be assessed on an individual basis, without the current facility to inherit or derive benefit rights from a spouse or civil partner. However, there will be transitional provisions to recognise shared or inheritable additional state pension accrued before the start date and also for certain married or formerly married women who paid reduced-rate National Insurance contributions

- income will be no less than the present state scheme

- income will be revalued under the ‘triple lock’ approach of the higher of earnings, prices or 2.5%

- option to defer but only for higher income, not a lump sum. The increase in the deferred pension will be at a rate about 50% of the current factor

- transitional arrangements to protect state pension rights accrued up to the start date of the new single-tier pension

- those with rights that are higher than the single-tier pension will retain these, called ‘protected benefits’, but they will only be increased by the CPI before and after SPA.

Where an individual’s existing benefits prior to April 2016 are less than the full single-tier pension, each additional year of qualifying service after the start date before they reach SPA will accrue further state pension entitlement of 1/35th of the full amount of the single-tier pension (i.e. £4.11 per week (£144/35) in current terms for each additional qualifying year), subject to their aggregate entitlement not exceeding the full single-tier amount.

For example, if Cindy had an existing entitlement (this is known as the ‘foundation amount’) of £50 per week, she could accrue additional state pension for each post-implementation qualifying year up to SPA subject to her aggregate entitlement not exceeding the full single-tier amount. In Cindy’s case this implies a further 23 years (£50 + (£144 x (23/35)) = £144), so if she is more than 23 years away from SPA, her final years of contribution will earn no extra pension benefit.

Private pensions

Registered pension schemes are subject to limits on funding and benefits, with tax charges levied on any excesses. Below is an outline of the main features of the different types of scheme, followed by the funding limits and planning considerations.

Defined benefit schemes

Where retirement benefits are provided by an occupational pension plan, whether a private- or public-sector type, and calculated on the basis of service, salary and an accrual rate, it is the pension scheme and, by association, the sponsoring employer that bear most of the risk and costs associated with providing the pension benefits. In this sense the overall benefits are predictable, but the future costs of providing them are not. For this reason most defined benefit schemes have closed to new members and many have closed to further benefit accrual for existing members as employers seek to minimise their future funding liabilities. Most public-sector schemes are not underpinned by financial assets to fund pension benefits and are therefore known as unfunded. Most private-sector schemes are supported by financial assets (to a greater or lesser extent) and are known as funded.

If your benefits have yet to be paid out, either because you are still working and accruing service or because you have left service before the normal retirement age, you need to check the financial position of the scheme and the commitment and financial capability of the sponsoring employer to continue to fund the scheme. Every three years the scheme trustees are required to provide an assessment of the scheme’s financial position and whether there are sufficient assets to secure all members’ pension benefits through an insurance company if the scheme were wound up at that time.

While this assessment can be seen as the worst-case scenario, it can often suggest that a scheme is underfunded when, on a going-concern basis, it is not. This is because securing pensions with insurance companies is very expensive. In addition, if the assessment has been carried out when investment markets have fallen sharply, this will overstate the underfunding, when in reality members take benefits at different times, thus providing the trustees with some flexibility to ride out short-term investment volatility.

If the pension scheme fails and is unable to pay out existing or future pension benefits, a government-sponsored scheme known as the Pension Protection Fund (PPF) will step in and provide benefits. If you have reached the scheme’s retirement age or are in receipt of an ill-health pension or where a survivor’s pension is in payment, the protected amount will be 100% of the pension in payment. Otherwise the protected amount will be 90% of the pension benefit, whether or not you have reached the scheme’s normal retirement age. The maximum protected pension payable is currently about £31,400 at age 65 but is lower for younger ages and higher for older ages.

Clearly, if you have a deferred defined benefit pension that is significantly in excess of £30,000 and/or the pension benefit represents a significant amount of the income that you expect to fund your lifetime spending, you need to be more concerned about the financial health of the scheme and possibly investigate whether it makes sense to transfer the cash value of your benefits to either your personal pension or your current employer’s pension scheme.

Other reasons why you might wish to transfer benefits, regardless of whether or not the scheme is in good financial health, include the following:

- You do not need the guarantees that the scheme provides and/or the benefits are insignificant in relation to your overall wealth and you are comfortable with taking on the investment and longevity (living too long) risks yourself.

- You envisage living abroad when you take benefits and wish to mitigate the currency risks by investing and eventually taking benefits in the currency of your new country of residence.

- You do not need some of the benefits that the scheme provides, such as spouse’s and dependants’ pensions, and would prefer to have a higher pension instead.

- You would like flexibility as to the level of benefits that you take from year to year, with the ability to vary these to suit your spending needs.

- You have little confidence in the scheme trustees and/or the employer to pay the expected benefits.

- You believe that you (or an investment manager) can obtain a better return on your share of the value of the pension fund than the scheme trustees.

- You wish to use your pension benefits to invest in a commercial property, possibly to be used by your business.

- You wish to access the capital value by way of regular or lump sum drawdown (see Chapter 18).

A defined benefit pension is potentially a very valuable benefit and can provide a good foundation to your wealth plan. However, if benefits have yet to come into payment, it will certainly be advisable to review regularly both how the scheme fits into your overall planning and the financial strength of the scheme and the sponsoring employer. Because assessing the merits of transferring a defined pension benefit can be complex, you will almost certainly need to consult an independent financial adviser who is qualified and authorised to give such advice. The fees for this type of advice can be quite high, particularly where the deferred benefits are significant, as this reflects the complexity of the work and additional risks to the advice firm.

Defined contribution schemes

In contrast to a defined benefit scheme, with a defined contribution (DC) scheme the contribution levels are known (if continuing), whereas the eventual benefits are not. The benefits that the scheme can provide will depend directly on the size of the fund (influenced by both contributions made and investment returns achieved) as well as mortality and long-term interest rates. Interest rates affect annuity rates, particularly at younger ages, which in turn will dictate the level of guaranteed income that can be secured with the fund or, alternatively until 6 April 2015, the maximum level of income that can be withdrawn directly from the fund. The member of a DC pension scheme, therefore, takes on all the investment and longevity risks themselves.

A registered pension scheme may invest up to 5% of its funds in the ordinary share capital of a sponsoring employer, up to four, as long as the total holdings in them are less than 20% of the fund value in total. The value is tested only at the time the investment is made and not subsequently. There is no restriction on how much of the sponsoring company’s shares may be owned by a pension plan and this could, in theory, be 100%.

There are two types of DC pension scheme: occupational and personal.

Occupational schemes

An occupational scheme is designed to provide benefits for the employees of a sponsoring employer and is subject to a detailed set of scheme rules and a trust deed. The benefits that the scheme can provide will be based on the value of funds earmarked for individual members, but will be subject to overall limits set by HMRC.

Another type of occupational DC pension is the small self-administered scheme, which was originally designed for controlling directors so that they could combine the benefits of pension tax relief with some flexibility to use their pension funds for business purposes. An SSAS must be established by a sponsoring employer for up to 12 employees, all of whom have to be trustees and who must make unanimous investment decisions. For this reason, an SSAS can be established by a company only if the members are also the owners of the business, because a sole trader or members of a partnership are classed as self-employed.

The scheme’s assets are pooled together and then allocated as required to cash deposits, commercial property, an investment portfolio or individual investment. Unlike a personal pension, an SSAS may lend up to 50% of the fund to the sponsoring employer for commercial purposes, subject to taking adequate security, the loan being repaid in regular instalments over a period not exceeding five years and the interest rate being at least 1% over the bank base rate. A loan may not be given for the purposes of keeping an ailing business afloat. An SSAS may also borrow (on normal commercial terms) up to 50% of its assets, which can be useful to help fund property acquisition.

Personal schemes

A personal scheme is an individual plan in the member’s own name and contributions can be made by the member, their employer, a third party or a combination of all three. There is no need for a sponsoring employer and all compliance with HMRC rules is handled by the pension scheme provider, not the employer. As a result, an increasing number of employers have put in place group personal pension schemes (GPPS) that combine the benefits of individual pension accounts with centralised payment and administration. Due to the obligations following the introduction of auto-enrolment in 2012 (more of which later), more group schemes are now being established.

Usually the plan is derived from a master scheme trust, from which it takes its rules and compliance with the tax rules for registered pensions. However, a small number of personal pensions can be established under an individual trust arrangement that has its own set of individual scheme rules, although in practice these are based on ‘model’ trust wordings. I’ll explain more about how and why you might want to use an individual trust scheme shortly.

Personal pensions can be provided by a wide range of suppliers, including investment groups, insurance companies and professional trust companies. Increasingly, schemes are being offered on what is known as a self-invested basis, otherwise known as a self-invested personal pension. This allows members a wide choice of investments for their fund, including commercial property. Alternatively, a member may appoint a professional investment manager to manage the investment of some or all their pension fund.

Auto enrolment

Pensions auto enrolment (AE) is a legal requirement on employers to ensure that all eligible employees are automatically enrolled into a pension scheme (known as a qualifying workplace pension scheme) with mandatory minimum contributions from the employer and the employee. Employers are required to do the following:

- assess eligibility of all employees

- register with the pensions regulator

- ensure that their pension schemes comply with all regulations

- manage the enrolment process for all employees

- manage and update the opting in and out of employees

- manage contributions

- ensure that inducements to opt out of auto enrolment are not offered

- provide regular updates and employee communications

- re-enrol opted-out employees on a regular basis

- keep accurate records of all the above.

Auto enrolment commenced in October 2012. However, to help businesses to prepare for the administration changes and costs, it is being introduced in stages (see Table 17.1). By March 2017, all employers will be required to auto enrol their employees into a qualifying scheme.

Table 17.1 Staging dates for auto enrolment

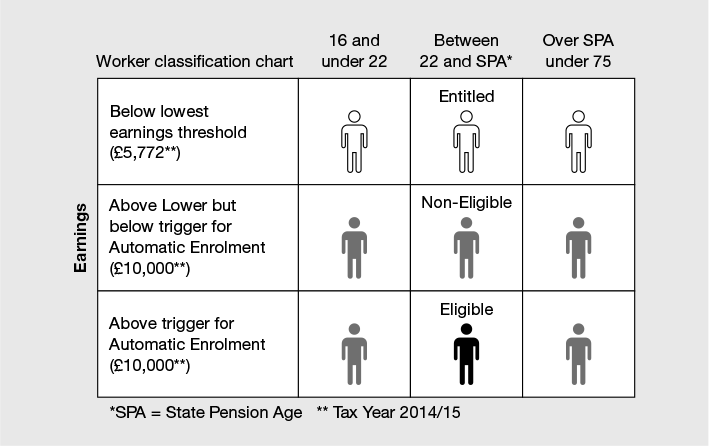

The eligibility criteria are based on a combination of the employee’s age and amount of earnings, as shown in Figure 17.2, based on the 2014/15 tax year. Future tax years will clearly have higher earnings figures and the SPA will increase over the next few years, as explained earlier.

Figure 17.2 AE employee eligibility and entitlement

Source: TAP Assist Limited.

Under AE the total contribution starts at an initial level of 2% of earnings, with 1% of this being an employer contribution (see Table 17.2). The contributions will increase in stages to 8% of earnings, with 3% of this being contributed by the employer by October 2018.

Table 17.2 AE contributions rates

* including tax rebate on pension contributions

Employers have to certify that they are meeting the minimum contribution requirements for a scheme under their AE requirements, where there is a mismatch between the definition of pensionable pay under an employer’s defined contribution pension scheme and that of qualifying earnings under the AE requirements. This quality test (see Table 17.3) runs for 12 months from the employer’s pension staging date to the anniversary, taking in all earnings types (basic pay, commission, bonus and overtime), and will allow the employer to calculate whether they have hit the 8% contribution rate on the threshold earnings levels of £5,772 and £41,865.

Table 17.3 AE quality test for contributions

| Total contribution | Employer contribution | Pensionable pay |

| 9% of pensionable pay | 4% | No quality test required |

| 8% of pensionable pay | 3% | Pensionable pay is at least 85% of the total pay bill for the workers |

| 7% of pay | 3% | All pay is pensionable |

The contribution limits

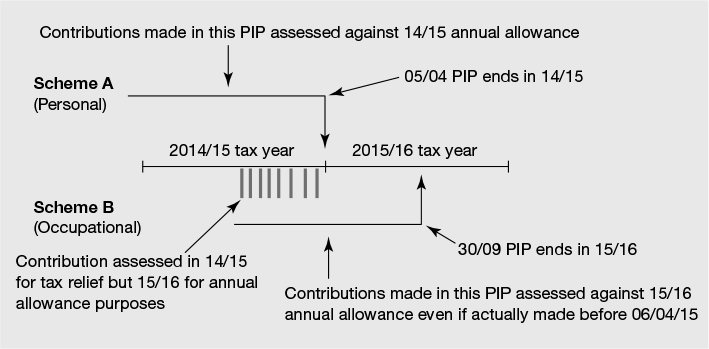

The annual allowance is the annual limit to the amount of tax-relieved pension contributions or benefit accrual that you can have through all pension schemes in a tax year. For the purposes of the annual allowance limit defined contributions or defined benefit accrual fall within a 12-month period known as a payment input period (PIP), which ends in a particular tax year. With new personal pension plans the PIP always runs in line with the tax year, but it can be changed by the member if desired. With occupational pension plans the PIP will be set by the scheme trustees and can’t be changed by the member. This can cause complications if, for example, the PIP of an occupational scheme ends on 30 September and the member wishes to also make contribution to a personal scheme which has a default PIP end date of 5 April. Because the occupational scheme PIP straddles two tax years, care is needed to ensure that the available annual allowance is correctly calculated. Figure 17.3 illustrates how this works in practice.

Figure 17.3 How the pension payment input period (PIP) works

The annual allowance is £40,000 for PIPs ending in the 2014/15 tax year and beyond, but previously it was £50,000. With defined contribution pension plans, the amount of any personal and/or employer’s contributions in a PIP ending in the tax year is the amount tested against the annual allowance. With a defined benefit pension scheme the benefit accrued in a PIP ending in the tax year is multiplied by 16 to determine the value for annual allowance purposes (with allowance given for inflationary increases).

Where you wish to make a contribution in excess of the current tax year annual allowance (currently £40,000), carry forward is available to the extent that, in any of the previous three years, you had a registered pension scheme and had unused annual allowance. The unused allowance is available regardless of whether you were permitted to make contributions in those years or not (perhaps because you had insufficient earnings or were non-UK resident). The surplus (starting with the earliest year) is then rolled forward to the current year to enable relief to be provided on the contribution made in the current tax year, to the extent that it exceeds the annual allowance. For the three years prior to 2014/15 the annual allowance was £50,000 and this amount may still be carried forward beyond 5 April 2014.

Although active (i.e. still accruing benefits) membership of defined benefit pension schemes is becoming rarer and mainly the preserve of public-sector workers, about 28% of UK employees are members of such schemes (whether active or deferred),6 so there is a fair chance of them featuring in many people’s wealth planning. A defined benefit pension is potentially a valuable financial resource, but it can cause complications with the annual allowance limit, particularly if you have a high salary and/or high accrual rate. If you exceed the annual allowance, this will cause a tax charge that negates the income tax relief given.

To help you to work out the maximum benefit that you can accrue in a PIP and remain within the annual allowance, you can use the formula set out in the box. If benefit accrual results in a pension input amount that exceeds the annual allowance (after accounting for any unused annual allowance that might be available to carry forward from the previous three years), you are required to disclose this fact in your self-assessment tax return and pay the associated tax charge.

Defined benefit accrual and the annual allowance

FORMULA I = (PIA)/16 + (C × Pension)

| I | = | increase in pension in a payment input period |

| PIA | = | payment input amount (increase in accrued benefits) |

| C | = | Consumer Price Index increase rate in the September before tax year in question |

| Pension | = | pension accrued at end of previous PIP |

Example

Hope had accrued £38,000 of benefit in the previous PIP ending 31 March 2014. The annual rate of the CPI to the previous September was 2%.

- (£40,000/16) + (0.02 × £38,000)

- £2,500 + £760

- £3,260

Hope can therefore accrue up to £3,260 of additional benefit in the PIP ending on 31 March 2015, i.e. the 2014/15 annual allowance.

Any personal contributions must not exceed 100% of earnings, although up to £3,600 per year can be contributed without any earnings. Employer contributions may be made without reference to the member’s earnings, although contributions to defined contribution schemes are, in aggregate with personal contributions, subject to the annual allowance (including any carry forward of unused annual allowance available). Tax relief on personal contributions is given at your highest rate by extending the basic-rate income tax band. A personal contribution can thus be used to:

- bring a 40% or 45% taxpayer below the threshold at which that rate is paid

- enable capital gains otherwise taxable at 28% to be taxed at 18%

- enable taxable gains arising on encashment of life insurance bonds to be taxed (in whole or in part) at nil, 20% or 25% depending on the size of the gain and whether the policy is an offshore or onshore type

- retain the personal allowance by bringing income below the £100,000 threshold.

Putting aside for one moment any investment returns arising, making pension contributions to a defined contribution scheme can be highly attractive for certain taxpayers due to the availability of a 25% pension commencement lump sum (PCLS) that is currently tax-free. Table 17.4 shows the uplift in value for different taxpayers, disregarding any investment returns. The best effect is where tax relief is obtained at a rate of 40% or more but benefits are taxed at 40% or less. Someone obtaining effective tax relief of 60% (those with taxable income over £100,000) but who pays only 20% on those pension benefits would obtain a staggering 113% uplift by making a pension contribution.

Table 17.4 Uplift in value of pension contributions assuming 25% tax-free lump sum

* This is the effective income tax rate for those with taxable income of between £100,000 and £120,000 due to the loss of personal allowance (2014/15 tax year)

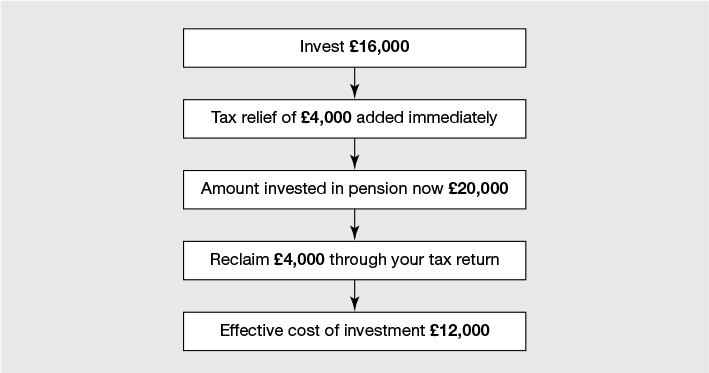

Contributions in excess of the current tax year’s annual allowance may incur a tax charge if there is no unused annual allowance to carry forward from the previous three tax years, which has the effect of clawing back any tax relief provided (see Figure 17.4).

Figure 17.4 How tax relief (40%) is given on pension contributions

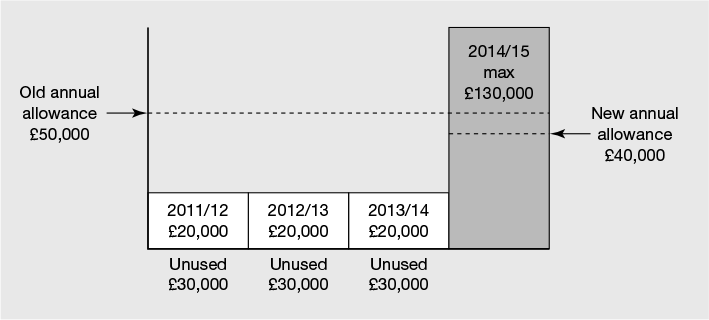

Figure 17.5 illustrates the position for Charlotte, who is a company director and has had a SIPP since 2008. She has a total of £90,000 unused relief available to carry forward to 2014/2015, allowing a maximum contribution of £130,000 to be made in that tax year.

Figure 17.5 Example of carry forward of unused pension allowance – 2014/15

As time goes on the carry forward calculations could become complicated. Let’s assume that Charlotte or her employer made a contribution of £90,000 in the 2014/15 tax year, making use of carry forward of unused annual allowance of £50,000 (£30,000 from 2011/12 and £20,000 from 2012/2013). In the 2015/2016 tax year she can still carry forward unused annual allowance of £40,000 (£10,000 from 2012/2013 and £30,000 from 2013/2014 tax years to enable her employer or herself (if she has sufficient earnings) to make a contribution of £80,000 (£10,000 + £30,000 + £40,000). See Figure 17.6.

Figure 17.6 Example of carry forward of unused pension allowance – 2015/16

This is a simplified example of how carry forward works. In practice, different circumstances will cause different outcomes and considerations, particularly if you have more than one pension scheme, and/or you have defined benefit pension schemes, and/or your historic contributions include one or more years in which you or your employer contributed more than £40,000. Great care is required to ensure that you do not inadvertently incur an annual allowance tax charge and this is an area where a good adviser can be very helpful. If you want to work out your available annual allowance, HMRC has a useful pension annual allowance online calculator tool at www.hmrc.gov.uk/tools/pension-allowance/index.htm

The lifetime limit

The total amount of benefit that you may accrue within all registered pension schemes is limited to an upper limit known as the lifetime allowance (LTA). There are several types of lifetime allowance:

- Standard – £1.25 million (from 6 April 2014).

- Individual protection 2014 – between £1.25 million and £1.5 million (must be applied for between 6 April 2014 and 5 April 2017).

- Fixed protection 2014 – up to £1.5 million (from 6 April 2014).

- Fixed protection 2012 – up to £1.8 million (from 6 April 2012).

- Enhanced – no limit (if applied for between 6 April 2006 and 5 April 2009).

- Primary – limit is the amount that the fund exceeded £1.5 million on 6 April 2006, increased by 20%.

For defined benefit pension schemes, benefits not in payment are multiplied by 20 to determine their value for LTA purposes. If your pension fund exceeds the available LTA when you take benefits, a tax charge will apply. This will be either 25% if you take the excess as an income, or 55% if you take the excess as a lump sum.

As a general rule it makes sense to avoid exceeding the LTA (although sometimes it is less of a problem) and therefore you need to monitor the effect of:

- any new proposed contributions

- the investment strategy and returns arising

- if and when to take benefits from the plan in the form of a tax-free lump sum and taxable income.

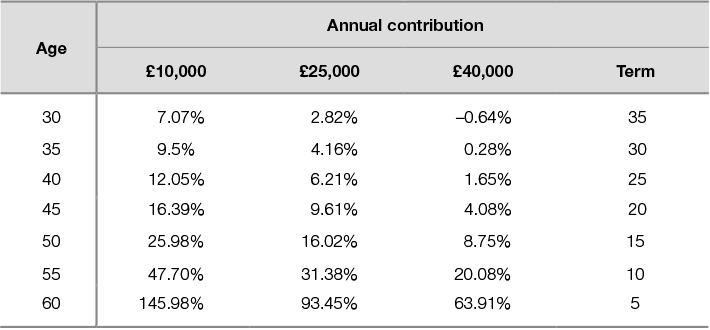

I’ll explain in more detail how best to manage your pension plan in the next chapter, but for now I just want to consider the lifetime allowance in the context of whether or not you make any new contributions. As illustrated in Table 17.5, if you have no existing pension provision, it is unlikely that you will exceed the lifetime allowance unless you contribute near to the annual allowance maximum and/or have a long time horizon before taking benefits and/or achieve quite high investment returns.

Table 17.5 Summary of growth required to reach standard lifetime allowance assuming no existing pension fund

*This is the effective income tax rate for those with taxable income of between £100,000 and £120,000 due to the loss of personal allowance (2014/15 tax year)

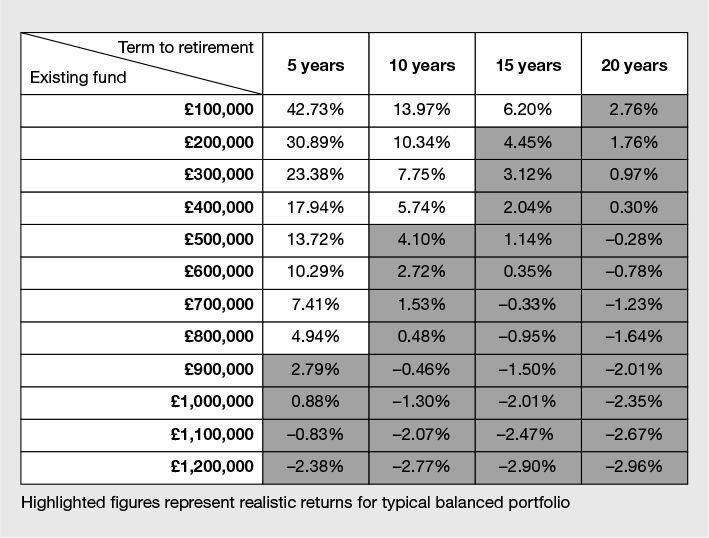

Figure 17.7 shows the annual investment return required to reach the lifetime allowance at different levels of existing pension benefits and terms assuming that ongoing contributions are made to a defined contribution scheme equal to the annual allowance of £40,000. Fund values in excess of about £600,000–700,000 with a term of more than five years need either low or negative returns to avoid breaching the lifetime allowance.

Figure 17.7 Annual growth required to fund £1.25 million lifetime allowance assuming £40,000 annual contributions with existing fund value

Qualified non-UK pension scheme (QNUPS)

This is the term given to most overseas pension plans that meet certain rules set down by HMRC. QNUPS fall into two types:

- Those that are classed as qualifying recognised overseas pension schemes (QROPS) because they qualify to receive a transfer of benefits from a UK pension scheme.

- Those that are not a QROPS because they do not qualify to receive a transfer in of benefits from a UK pension scheme.

The key benefits of a QNUPS, which is not also a QROPS, are as follows:

- There is no limit on the amount that may be contributed, although no tax relief is given.

- Non-UK-sited investments usually grow free of UK taxes.

- Potential to avoid tax on amounts taken as a lump sum.

- Potential to borrow between 25% and 50% of the fund, depending on the jurisdiction.

- Ability to invest in a wide range of investments, including residential property.

- No UK inheritance tax on the value of the fund as long as it is being used as a proper retirement plan.

In the 2014 budget, the government announced that it would consult on the tax treatment of QNUPS, with the intention of preventing inheritance tax avoidance.

With the exception of defined benefit plans, pension plans are merely tax wrappers within which one can hold some wealth to achieve a tax effect. The tax reliefs on offer – income tax relief on contributions, largely tax-free growth and freedom from inheritance tax – are very attractive. In the next chapter I’ll explain how best to manage pension assets in the context of your overall wealth plan.

1 Pensions Policy Institute (2010) ‘Submission to the Work and Pensions Select Committee on the government’s pension reforms’, p. 4.

2 Public Bill Committee on the Pensions Bill 2013 (transcript), 4 July 2013.

3 Money Advice Service – Annuity comparison service for best standard RPI linked annuity for person aged 66 (accessed 25 March 2014).

4 Money Advice Service annuity comparison April 2014.

5 Following a change of government in 1975 no additional state pension was provided until SERPS started on 6 April 1978.

6 Office for National Statistics, Pension Trends – Chapter 7: Private Pension Scheme Membership, 2013 Edition, p. 11.