LATER LIFE PLANNING

‘One of the most attractive things about writing your autobiography is that you’re not dead.’

Joseph Barbera, American animator, director, producer

As Chapter 3 showed, we are all living much longer and the outlook is for life expectancy to continue to increase, but perhaps not at the same rate as it has over the past 30 years or so. Increased life expectancy, however, also brings with it a multitude of issues that may have a bearing on your wealth planning and possibly that of your parents or relatives.

Dementia is one of the main causes of mental incapacity in older people in the UK, affecting about 800,000 people, and this number is set to rise to more than 1 million people by 2025.1 The chances of suffering dementia increase significantly with age and roughly double with every five-year age group.

Power of attorney

A lasting power of attorney (LPA) is a legal document that provides one or more people (known as attorneys) whom you appoint to deal with your affairs as if they were you, subject to certain conditions and obligations. LPAs replaced enduring powers of attorney (EPA) in England and Wales in 2008 – although EPAs executed prior to the change remain valid, no EPAs may be created since 1 October 2007. In Northern Ireland LPAs are governed by slightly different rules. The equivalent in Scotland is known as a power of attorney and the rules are also slightly different to those applying in England and Wales.

An LPA is arguably more important in your later life stages, given the higher likelihood of losing mental capacity compared with middle age. Ensuring that someone has the legal means to make important legal, financial and medical decisions on your (or your parents’) behalf when you (or your parents) are not capable of making those decisions is a prudent and responsible piece of forward planning.

A person acting as an attorney must follow certain principles that govern what they can and cannot do. These principles include:

- acting only within the powers set out in the LPA

- acting in the best interests of the donor

- involving the donor in decision making as far as possible

- not taking advantage of the donor’s situation to benefit the attorney personally

- keeping property and money separate from the attorney’s.

In England and Wales an LPA must be registered with the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) in order to be valid. However, because it can take up to four months to register an LPA I recommend that you register it at the outset to avoid delays if it needs to be used. LPAs can be wide-ranging, including allowing your attorney to sell property, operate your bank accounts or even provide guidance as to what type of health treatment you would like to receive in certain scenarios. Alternatively, you could make your LPA limited in scope to deal with only a narrow range of scenarios.

The old-style EPA needs to be registered with the OPG only in the event that it is to be used when the person subject to the EPA (known as the donor) has lost mental capacity. If the donor hasn’t lost mental capacity, the EPA can be used without being registered, although there can be practical difficulties with banks and investment providers refusing to deal with an attorney where the EPA is unregistered.

In England and Wales there are two types of LPA: a property and affairs LPA, which covers financial and legal issues, and a personal welfare LPA, covering things such as where you will live and medical preferences. Since 2005 it has also been possible to create what is known as an advance decision to state preferences for medical treatment that one would like or not like if one were no longer able to decide for oneself.

If you have strong views on medical treatment, you should set these out in either a personal welfare LPA or an advance decision, but ensure that your general practitioner and your next of kin know about it. In most cases a personal welfare LPA will override an advance decision as long as the LPA is prepared after the advance decision and it specifically confers authority on the attorney.

If someone loses mental capacity but they have not established an EPA or LPA, it is possible for a friend or relative to make a deputyship application to the Court of Protection. The Court will then consider conferring specific powers on the prospective deputy making the application, to deal with the person’s legal and financial affairs, together with various legal obligations. The Court also has power to appoint someone else as the deputy if they think the applicant isn’t suitable (e.g. they have a criminal record).

In Scotland, a power of attorney (PA) can include powers to deal with financial assets (known as ‘continuing powers’) and/or personal welfare. While continuing powers can be conferred for use regardless of the mental capability of the person subject to the PA, they can be used for welfare-related aspects only if the subject has lost mental capacity to make such decisions. All Scottish PAs must include a certificate signed by a Scottish legal professional or medical practitioner to the effect that the person granting the PA is making the decision freely and understands the implications. Before it can be used the PA must be registered with the OPG in Scotland.

In Northern Ireland, an LPA must be registered with the Office of Care and Protection (OCP) if it is to be used when the subject of the LPA has lost mental capacity.

Making wills in old age

There are a number of potential problems associated with older people making wills, particularly when they deprive relatives of inheritance. The case of Golda Bechal highlights these.2 Mrs Bechal left her £10 million estate to a couple who ran her favourite Chinese restaurant, to the detriment of her immediate family. The family contested the will on the basis that Mrs Bechal executed it without being fully aware of what she was doing. The case was eventually settled in favour of the beneficiaries of Mrs Bechal’s will but not until after several years of legal wrangling.

Another case involved Dr Christine Gill, whose parents, John and Joyce Gill, had left their entire estate of more than £2 million to the RSPCA charity.3 The court was told the Gills were a ‘very close family’ and there had been no major rifts to explain cutting their only child out of the will. Indeed, the daughter did thousands of hours of unpaid work helping to run the family’s 287-acre farm and selflessly supported her troubled mother, Joyce, who suffered from various phobias.

Dr Gill argued in court that her mother had been coerced into making the will by her ‘domineering’ father, John, who died in 1999. Judge James Allen QC said Mr Gill was a bully and a ‘stubborn, self-opinionated, domineering man, who was prone to losing his temper’. His wife, a shy woman, deferred to what he wanted, said the judge. In 1993 Mrs Gill signed a will leaving everything to the RSPCA, despite being said to have an ‘avowed dislike’ of the organisation. Judge Allen found that Joyce Gill had been coerced into making a will that was against her wishes and awarded the estate to the daughter.

To avoid disputes about your (or any elderly relative’s) will after death, you need to prove that you (or your relative) had ‘testamentary capacity’ (i.e. you had the mental capacity to make decisions) at the time the will was made. Although the test for testamentary capacity is not quite the same as the medical test for mental capacity, it is still a good idea to obtain a statement from your family doctor that confirms you have mental capacity. In addition, to avoid legal claims from those with legitimate claims as your ‘dependants’, you should make reasonable provision for them in your will. Otherwise such individuals might be able to contest your will.4

Nevertheless, all is not lost if someone loses mental capacity to make a will as it is possible to create a statutory will providing that the person wishing to make the will is either an attorney under a registered EPA or LPA or has been granted a deputyship by the Court of Protection and subsequently applies to the OPG with a formal proposal for the terms of a statutory will. However, sophisticated estate planning is unlikely to figure highly on the list of permitted actions.

Long-term care fees

Much attention is focused on the issue of long-term residential care costs and the impact they can have on a family’s wealth. The consensus of all the available research seems to be that one in three people will need some form of long-term care. In many situations, funding care fees while remaining in your own home can actually be more expensive than residential or nursing home care costs, because of the need to meet the cost of care and of running and maintaining the home. It has been estimated that the average cost of care at home for just two hours a day would amount to £7,300 per annum.5 My own experience from working with clients is that 24-hour live-in care can easily cost more than £100,000 per annum.

On average, an individual can expect to pay around £27,612 a year for a residential care home, rising to more than £38,000 if nursing is required.6 However, the cost of residential or nursing home care varies widely depending on the location, as illustrated by Table 19.1. The average life expectancy for those entering residential care is about 2.5 years.7 However, if we remove from the statistics those severely sick and disabled people who are admitted to care homes straight from hospital, the average stay in a care home for a self-funder (i.e. someone not receiving state care fees funding) is actually closer to four years, with a one in eight chance of living more than seven years.8

Table 19.1 Average weekly care home fees around the UK 2012/2013

| Weighted average weekly fees by region – private homes for elderly people, UK 2012/2013 |

||

| Area | Residential care home | Residential nursing home |

| England – average | £532 | £750 |

| North East | £471 | £597 |

| North West | £468 | £663 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | £463 | £624 |

| East Midlands | £506 | £618 |

| West Midlands | £495 | £708 |

| East of England | £564 | £800 |

| London | £598 | £821 |

| South East | £591 | £869 |

| South West | £551 | £764 |

| Scotland | £555 | £685 |

| Wales | £491 | £650 |

| Northern Ireland | £466 | £570 |

Source: Laing & Buisson, ‘Care of elderly people UK market survey 2012/13’.

Care costs are fully funded by the NHS if the ‘primary’ need is for healthcare. This is assessed by the NHS when the patient is discharged from hospital or moves into a care home and since 1 October 2007 has been covered by the National Framework for NHS Continuing Healthcare and NHS-funded Nursing Care. However, like hospital stays, such funding affects an individual’s entitlement to a state pension and certain other benefits. In addition, the individual has no say in the choice of care provider or establishment.

Part-funded care: non-means tested

If a registered nurse assesses that an individual needs nursing care as part of their care needs, the NHS will, regardless of that person’s wealth or income, contribute a flat weekly rate (at the time of writing this is £106.30 in England and £119.66 in Wales). If the assessment was carried out before 1 October 2007 and the person qualified for the higher rate of nursing care funding, this will continue (this is £146.30 in England and Wales).

The situation in Scotland is different in that those aged 65 and over who self-fund their care benefit from an NHS contribution towards nursing and personal care (this currently amounts to £222 per week). Those aged under 65 benefit from a contribution towards personal care only (this is currently £69 per week).

Means-tested care fees funding

Means-tested care fees funding is assessed and provided by the social services departments of local authorities. Each local authority can choose its own eligibility criteria, although national guidelines set out the core rules and legal obligations. As a general rule any person who is assessed with having more than a modest amount of income or capital is not eligible for means-tested care fees funding (see Table 19.2).

Table 19.2 Capital limits for care funding 2014/2015

Source: Department of Health (2014) ‘Charging for Residential Accommodation Guide (CRAG)’, April.

The current capital upper limit of £23,250–26,000 means that most affluent people will need to fund all of their care fees, at least until their capital falls below the upper limit. A reducing scale of support applies between the lower and upper capital limits, based on you contributing £1 a week for every £250 in assets over £14,250 (in respect of those living in England).

Certain assets are excluded from the means-tested care fees funding assessment, including:

- an individual’s home that continues to be occupied by a spouse, civil partner or someone living with the claimant as a spouse or civil partner

- an individual’s home that continues to be, or is intended to be, occupied by a relative aged over 60 or who is incapacitated

- the proceeds of the sale of the home to the extent that the capital is used to buy a replacement property for the resident spouse, civil partner or qualifying resident

- previous outright gifts to individuals or trustees as long as these were not, and can’t be shown to have been, made with an intention to deliberately avoid paying care fees

- the surrender value of life insurance policies, including investment bonds but not capital redemption bonds.

Proposed changes to care fees funding

There are two major changes proposed for long-term care fees funding over the next few years. Starting from April 2015, individuals requiring care may defer paying towards their care costs, under a ‘universal deferred payment’ arrangement that will enable them to defer payment of care costs until after their death by taking a local authority loan that would be secured on their home. A number of local authorities already offer deferred payment arrangements on a discretionary basis.

The second and more welcome change relates to the roll-out of a national minimum eligibility assessment for support. The basis for assessing eligibility for care will be simplified and harmonised to stop the postcode lottery that currently exists. Whether this is achievable in practice, with hard-pressed local authorities, remains to be seen. No one aged over 65 will have to meet care costs if these first arise after April 2016 and they have assets worth less than £14,250. Those with assets between £14,250 and £118,500 will have to meet some of the costs of residential care up to a cap of £72,000 for ‘eligible’ care costs, which are within the local authority’s assessment of what it will pay towards this cost. If the person requiring care cannot find a residential care home to deliver this care at this price, or they cannot find one they like within this budget, the individual or their family will have to ‘top up’ the difference. These additional payments will not count towards the care cap. In any case, those needing care will still have to pay towards the cost of food and accommodation, and this has been set at a maximum of £12,000 per annum. It is estimated that the new cap will benefit the 16% of older people who face care fees of more than £72,000.9

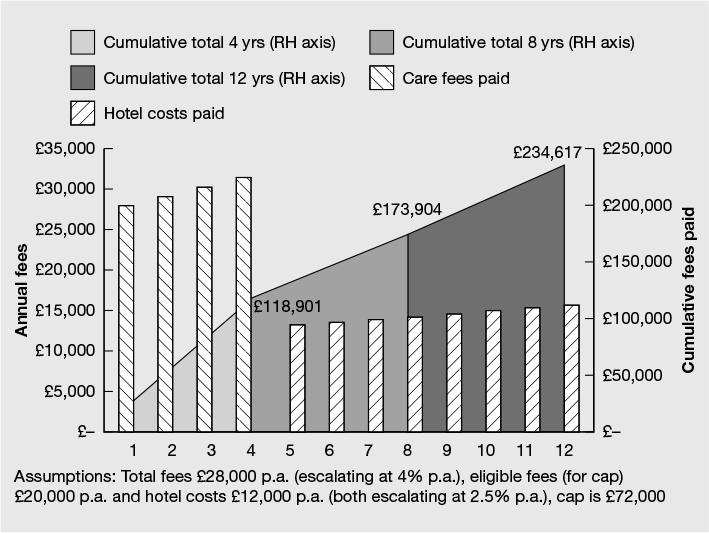

Figure 19.1 projects the cumulative care costs for someone who has capital above the proposed new upper limit of £118,000 throughout, based on the average annual care costs for England. Clearly, the length of time that care is required has a large impact on the cumulative total cost to the individual, with this varying from £120,000 for four years, £174,000 for eight years and £234,000 for 12 years in the projection. One point to note is that the proposed care fees cap of £72,000 is met only after just over 3.5 years, because I have assumed that the local authority definition of the individual’s contribution to ‘eligible care’ is £20,000 compared with the actual cost of £28,000. This seems a reasonably prudent basis on which to assess the potential liability to personal wealth. An additional point worth making is that the cost of the better quality care homes and those in London and the South of the UK will almost certainly be greater than the £28,000 used in the example, as will the difference between actual cost and ‘eligible care’ costs for the purposes of the cap.

Figure 19.1 Illustrative cumulative care costs

Interestingly, parents of those under 18 requiring care will not have to meet any of their care costs because the care fees cap will be zero. People requiring care between the ages of 18 and 65 with assets above the £14,250 capital threshold will have to meet some of those costs but with a lower, yet to be decided, cap than the £72,000 that applies for those aged 65 and over.

Protecting assets from assessment

If the local authority can prove that the individual (or their attorney) deliberately deprived themselves of assets to avoid paying care fees, then the local authority can seek payment from the recipient of the capital, including placing a charge on any assets. Although any transfer of assets made by the individual within the six months before they required care will always be treated as a deliberate deprivation of assets, in theory the local authority can go back many years before that if it thinks it has sufficient evidence that avoiding care fees was the main motivation for giving away assets or capital.

The whole issue of deliberate deprivation of assets is a bit of a ‘grey’ area as the test will depend on the facts of each case as well as a degree of subjectivity. Any preventative planning needs to be done in the context of one’s overall wealth plan and should avoid the accusation that ‘[while] avoiding the charge need not be the main motive … it must be a significant one’.10 The guidelines state that it is reasonable to ignore disposals made when the individual ‘was fit and healthy and could not have foreseen the need for a move to residential accommodation’. The length of time between any planning action and requiring care funding would seem to be an important element of any defence against a charge of deliberate deprivation of assets.

Maximising state funding of care fees

The following planning areas are worth considering as part of your wider wealth plan as they may minimise how much you and/or your spouse or civil partner have to pay towards care fees:

- Make gifts to a discretionary trust from which you can’t benefit and which is done for the purpose of minimising inheritance tax while you are in good health.

- In your will, direct an amount equal to the available nil-rate band to a trust from which your surviving spouse (and wider family) can receive benefit, ideally by way of loans (as well as outright income and capital), for the purpose of providing flexibility over who can benefit and to minimise inheritance tax.

- Make a nomination for any uncrystallised pension lump sum death benefit to be paid to a pension bypass discretionary trust that will allow your surviving spouse (and wider family) to receive benefit, ideally by way of loans (as well as outright income and capital), for the purpose of providing flexibility over who can benefit and to minimise inheritance tax.

- Effect a discounted gift trust (which is explained in more detail in Chapter 21).

- Consider using your home and a trust structure to carry out inheritance tax planning, taking care that the main objective is inheritance tax planning and it is effective.11

- Hold capital within an onshore or offshore life insurance investment bond.

- Buy an immediate needs deferred care fees annuity from an insurance company to transfer the risk of living longer than average.

Protecting the family home against care fees

Where the family home is owned jointly by a married couple or civil partners as joint tenants, each person’s share will, upon their death, pass automatically to the surviving spouse/partner, regardless of what their will states or the rules of intestacy. This means that any future means test for care fees funding for the survivor will be based on the entire property value, as and when they have been receiving residential care for six months.

If, however, the couple severs their joint tenancy in favour of owning it as tenants in common, on the death of the first of the joint owners to die, his or her share can pass, via their will, to a third party (or to a trust). This means that only the half share that is owned by the survivor will be taken into account for the purposes of any means test assessment should he or she subsequently need residential care. As no gift has been made by the surviving client, this strategy does not count as deliberate deprivation despite its effectiveness in ring-fencing the home.

The value of any property should also be disregarded for a residential care fees assessment if it is ‘occupied in whole or in part as their home by the resident’s other family member or relative who is aged 60 or over’.12 However, the High Court recently prevented a local authority from selling an elderly lady’s house to pay for her care fees, on account of the fact that the woman’s daughter had demonstrated a degree of attachment to the property, despite not actually living there permanently.13 The relative argued that, although she rented a studio flat in London (where she worked), she considered her mother’s property to be her permanent home. This was evidenced by the considerable sum she had spent maintaining it, the fact that she had kept a bedroom, office and shed there for her own use, and her intention to retire there in the near future. The local authority rejected her arguments saying that her occasional occupation of the property could more accurately be likened to a person’s occupation of a holiday home.

Defining home as ‘a place to which a person has a degree of attachment both physical and emotional’, the judge concluded that the local authority had incorrectly interpreted and applied the test (by apparently applying a test of actual occupation and/or permanent residence) and ordered it to ‘redetermine’ its decision in accordance with the terms of the judgment.

This is the first occasion that this particular issue has come before the courts and while the local authority was, at the time of writing, planning to appeal against the decision, the case may set a precedent for others if allowed to stand. Even then, however, the scope of similar claims is likely to be limited to children over the age of 60 who have invested in, or shown other forms of commitment to, the property.

Life assurance bonds

Although some local authorities do try to include investment bonds in care fees funding assessments, the legislation and guidance are quite clear that such capital must be disregarded.14 However, any ‘income’ taken from an investment will be assessed as income for fees funding purposes, but if the ‘income’ is stopped when care fees start, such income will then cease to exist and, as such, will be disregarded under means testing. A capital redemption bond is not one that is treated as providing life insurance and therefore is not disregarded for care fees funding assessment.

Immediate care fees annuity

It is possible to take out care fees insurance by way of an immediate needs annuity when you know that you have to fund care fees. Whether buying a care fees annuity is a good use of family wealth or not depends on for how long care fees need to be paid, the cost of the care fees annuity, the impact that care fees will have on the family wealth and the extent to which preserving wealth for other family members is a priority. Immediate care annuities are useful if you would prefer to make a known payment up front in return for passing to an insurance company the risk of meeting the agreed level of fees for the rest of your life.

There are only a handful of insurers active in this market and the maximum amount of fees benefit is usually limited to £5,000 per month. While care fees benefit can also be protected against general inflation, care fees inflation has, historically, risen at a higher rate. Therefore, claims over the long term might see the cost of care exceed the insurance benefit.

The reality of care fees funding

Most people want to know that they will have a choice about the type and quality of care, if required, that they will receive in later life. Financial planning that has the effect of avoiding having to fund care fees means you will, to a large extent, give away your choice to the local authority. This may not be a desirable objective. However, you might be of the opinion that any planning that has, as a long-term additional benefit, the potential outcome of giving you and your family the choice of whether or not to use family wealth to fund care fees, either wholly or to top up local authority funding, is better than not having the choice.

The reality for most affluent and wealthy people is they will have to use their own income and capital to fund a substantial element, of the cost of any long-term care fees that might arise in later life. The important questions that you need to ask yourself are:

- What quality of care would you wish to have if you needed it and how much is it likely to cost?

- Would the anticipated care costs be higher than the amount your local authority would classify as ‘eligible’ care costs and if so how much would you be likely to pay in addition to the proposed eligible care cap of £72,000?

- What impact will funding capped and uncapped care fees and accommodation costs have on your overall wealth and your ability to leave a legacy to your family, friends and/or causes?

- What implications for your investment strategy arise from potentially funding long-term care fees?

- What risk does long-term care represent to you given your family history, current and anticipated health status, and your views about government-sponsored assistance?

A good wealth planning strategy, coordinated by a caring and knowledgeable financial planner, should help you to find the answers.

1 Alzheimer’s Society (2013) ‘Dementia – the hidden voice of loneliness 2013’, infographic available at www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1409

2 London Evening Standard (2008) ‘Thanks for the tip: Restaurant keeps £9 million from favourite customer’s £10 million contested will’, 28 June.

3 Brooke, C. (2009) ‘Daughter wins back £2 million estate left to RSPCA after overturning parents’ will’, Mail Online, 10 October.

4 The Inheritance (Family and Dependants) Act 1975 provides certain protections for family members and dependants who have not been adequately provided for financially as a result of the deceased’s will.

5 Partnership Insurance estimate 2014.

6 Laing & Buisson, ‘Care of elderly people UK market survey 2012/13’, based on average figures for the UK.

7 Personal Social Services Research Unit (2011) ‘Length of stay in care homes’, January.

8 Partnership Insurance internal estimate.

9 Source: Department of Health (2013) ‘Policy statement on care and support funding reform’, February.

10 Department of Health (2010) ‘Charging for Residential Accommodation Guide (CRAG)’, para. 6.062, The Stationery Office.

11 The Law Society advises its members against planning using the family home but you might disagree.

12 Paragraph 2(1)(b)(ii) of Schedule 4 to the National Assistance (Assessment of Resources) Regulations 1992 (as qualified by Section 7 of the CRAG (Charging for Residential Accommodation Guide) rules).

13 Walford, R (On the Application of) v Worcestershire County Council [2014] EWHC 234.

14 National Assistance (Assessment of Resources) Regulations 1992, Schedule 4, para. 13; Department of Health (2010) ‘Charging for Residential Accommodation Guide (CRAG)’, para. 6.002B, The Stationery Office.