PROPERTY AND LAND

‘It’s tangible, it’s solid, it’s beautiful. It’s artistic, from my standpoint, and I just love real estate.’

Donald Trump

Many people love property, perhaps because, unlike an investment portfolio, it is tangible and they feel that they understand it. Everyone’s got to have somewhere to live and businesses need premises from which to trade. In this chapter we’ll examine residential investment property, agricultural property and land/woodlands, so you can consider what role, if any, they play in your overall wealth strategy.

Residential rental property

In the UK we have an obsession with residential property and for various reasons we seem to think that it represents a type of investment ‘get out of jail’ option. There’s no doubt that many have made good money from buy-to-let investments which have, as a consequence, attracted many followers into an investment strategy that seems to be a sure thing – buy a property, get a mortgage, pay the mortgage with the rent, take some extra income each month and sell the property for a big capital gain. If only it were so straightforward. Much of this success has been down to timing and luck in many cases.

Savings interest is at an historic low, with variable rates below 2% p.a. In fact, over the three years to the end of June 2014, the value of a saver’s assets has decreased in purchasing power terms by more than 10%. Against this backdrop a gross average annual yield of 5.6% (the consensus1 at the time of writing) would appear to make residential property an attractive alternative. However, as I’ll demonstrate, when you take into account maintenance costs, arrears from bad tenants and void rent (where no rent is received due to the property being empty), you’d be lucky to get 3.5% net and that’s before tax, inflation and any borrowing costs.

Some believe that the equity market has been disappointing over the past decade or so. Only a few years ago the headlines were of ‘the lost decade’ in terms of stock market investment. In fact, from the start of 2000, which was the height of the market before the dot com crash – so a pretty tough place from which to measure – to the end of April 2014 the UK equity market, with dividends reinvested, was actually up 72% and even stripping out inflation its purchasing power rose by around 14%. Emerging market equities would have more than doubled your purchasing power during this period. A well-structured portfolio, as we will see later, did a remarkable job during an emotionally tough period for investors.

While there are clearly a number of people who have made money out of residential buy-to-let property, as the market has grown over the past 15 years, most of this arose from unsustainable growth in capital values fuelled by cheap money and lax lending activity by financial institutions. There are a number of factors that will affect whether residential buy-to-let makes sense as a viable long-term investment. Tenant demand has risen steadily over the past five years or so, in the face of increasing prices and reduced mortgage finance. Estate agents would have us believe that tenant demand will continue to grow in the future.

Recent reforms to housing benefit are also likely to have a negative impact on overall rent levels. It is undoubtedly the case that high rents paid for some social tenants, particularly in London, had been pushing up rents across the board. Therefore, cutting state funding of the most expensive social housing must have a negative impact on overall yields. The average yield masks regional variations. For example, in January 2014 the yield in Scotland was 6.6% compared with London where it was 4.8%.2 Single properties let to multiple tenants, like students, can offer yields as high as 10%.

‘Beyond the nationwide figures lies an even more complicated picture. Local trends can be highly detailed, while dozens of different factors can affect the rent for any given property. Ultimately the ever-changing patterns of demand and the availability of local property at any given time will keep very local patterns in a constant state of flux. Some good deals are always there to be had, for tenants and landlords alike, if they have the right information.’

David Newnes, LSL Property Services plc3

Even if rents can be maintained at current levels, it still looks challenging to make a decent return once the true costs of repairs and maintenance are accounted for. Add in the strong probability of loan interest costs rising in the near term, the potential for rent voids and having a bad tenant and the chances of experiencing negative cashflow look likely.

When individuals enter the buy-to-let market with borrowed money, they are in fact starting a highly geared business with all the costs, tax and reporting issues and material risks that go with the territory. Successful buy-to-let enterprises have to be run in a disciplined and professional way if they are to avoid, or at least mitigate, the very material financial risks that they entail. Investors who go into the buy-to-let market without anything more than a naïve set of gross yield numbers, basic cost estimates and the hope of a rising market may not get the sort of outcome for which they are hoping.

The impact of borrowing on returns

If a good friend advised you that they were going to borrow up to three times the value of their investment portfolio to ‘gear up’ their investments, you’d rightly be concerned. Yet for many buy-to-let property investors this seems a perfectly sensible and clever way to make their money work harder. Property investing provides an easy opportunity to leverage or gear up their capital. Most buy-to-let mortgages demand around one third of the value of the property to be put down as a deposit – if you buy a £150,000 house you can put down £50,000 and borrow £100,000. Obviously, you could put down all £150,000 if you have it and not borrow anything. That choice will depend on your individual circumstances and risk preferences. Using debt to help fund investment property acquisitions might well not feel that risky, given that you may have experience of managing a mortgage on your home.

For those who go down the borrowing route, the reward on their capital – and risk on the flip side of the equation – increases in line with the multiple of their capital that they borrow. For example, disregarding borrowing costs, if the property increases in price by 20% over a period of time, the geared investor in the example above will make £30,000, which on their capital invested is a return of 60%. If, however, the market declines by 20%, they will lose £30,000 of their £50,000 capital invested (a 60% loss). Borrowing to leverage assets cuts both ways. It is possible to lose more than the value of your equity capital – for example, a fall of 35% in the property value would wipe it out. This is the curse of negative equity.

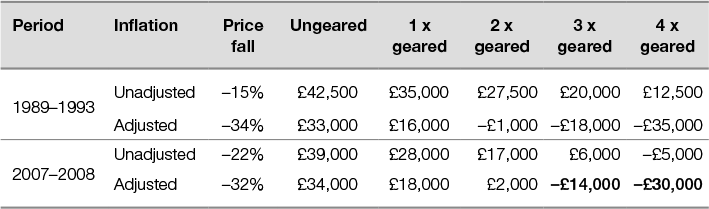

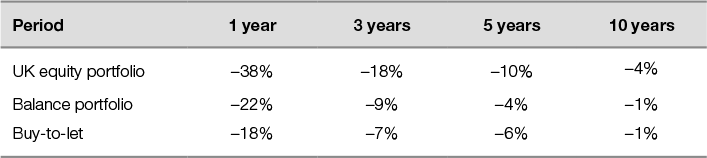

There have been two big falls since the mid-1980s, starting in 1989 and 2007 respectively. Property values around the country fell by between 20% and 35% on both occasions, as you can see in Table 9.1, which provides some insight into these two big falls and is a reminder of the magnitude of the capital losses that investors would have suffered in these periods.

Table 9.1 Gearing magnifies losses – effect on £50,000 equity capital

Source: Albion Strategic using data from Halifax UK All House Price Index. Morningstar Encorr. All rights reserved 2014. Bold = negative equity.

On the upside, an investor investing in 1983 would have doubled the purchasing power (after inflation) of their capital with no gearing, based on the house price appreciation alone and before any positive yield on the property (February 1983 to December 2012).

Working out the net yield

If the average gross buy-to-let yield in the UK is currently around 5.6% and the average rent is £800 per month,4 this implies an average property value of around just £171,500. We must also include the costs of a buy-to-let investment, which come in three stages: initial purchase and set-up ready for tenants, ongoing costs and, eventually, sale costs. Investors need to keep a tight record of all of these items for tax reporting. A cashflow model is essential to begin to understand the rewards and undoubted risks of running a geared (or even an ungeared) buy-to-let business.

Initial costs: initial purchase and setup include the costs of purchase that all homeowners know only too well, including stamp duty (1–7%) and professional fees. The property may well need to be repaired and redecorated, white goods installed, new furnishings purchased if it is to be let furnished, as well as gas and electrical equipment checked and certified.

Ongoing costs: these break down into annual costs and longer-term amortised costs to cover longer-term maintenance items. Property is a naturally depreciating asset – it falls to pieces, over time, if not looked after properly – and you need to invest hard cash into it to maintain or grow its value. Annual costs include insurance costs for buildings, landlord cover and utility and white goods maintenance, perhaps. You also need a general maintenance budget of, say, 1% of the property value for smaller items. If you buy a leasehold building then you may well have an annual service charge/sinking fund contribution to pay as well as the ground rent on the property. Many buy-to-let investors also use agents to manage the property to take some of the hassle out of it – a charge of 10–15% of the monthly rent is quite normal for this. There may well be void periods when no suitable tenants can be found and no rental income is being received. Finally, mortgage payments need to be deducted from the gross yield. Current mortgage rates with a 30% deposit are in the region of 4.5%, often with a hefty up-front arrangement fee.

The longer-term costs that are often either overlooked or grossly underestimated include repairs to boilers, central heating and appliances or worn-out showers, cookers, carpets, etc. – it is surprising how quickly rented accommodation begins to look shabby. The property will probably need to be redecorated every 3–5 years. Kitchens and bathrooms may need replacing every 5–10 years and don’t forget guttering, gardens, drains, roofs, wiring, drives, etc. that need some long-term care and attention. Tired-looking properties are hard to rent in an increasingly competitive and discerning rental market.

Scouring the internet5 you can begin to get a feel for what these costs are in aggregate from those who have been doing this for some time. The best rule of thumb appears to be to expect to budget for around 30–35% of the gross income for all general ongoing costs, before mortgage repayments. Any income remaining after costs – most of which are allowable against tax, including mortgage interest – will be taxed at the investor’s marginal rate.

Sale costs: finally, if you sell the property you will have to pay agent’s fees and capital gains tax at the prevailing rate (currently 18–28%), although if the investor lives in it for a certain period of time they may be able to deem it to be their primary residence and thereby reduce the amount of tax payable. However, that may not suit some investors, either practically or morally.

So, when some basic numbers are calculated, the true net yield is far less compelling than the news headlines. These basic calculations are set out in Tables 9.2 and 9.3.6

Table 9.2 Assumptions used in the example

| Basic assumptions | £ | % |

| Annual rent | £9,600 | |

| Gross rential yield | 5.6% | |

| Occupancy % | 95% | |

| Property value | £171,429 | |

| Investor’s capital | £50,000 | |

| Interest only mortgage | £121,429 | |

| Mortgage interest rate | 4.5% |

Table 9.3 Net yields aren’t great

| Monthly budget | In | Out |

| Monthly rent | £800 | |

| Vacant periods | £40 | |

| Monthly maintenance/management | £250 | |

| Mortgage interest | £455 | |

| Net income | £55 | |

| Net rental yield before tax (on property value) | 0.38% | |

| Tax @ 40% | £22 | |

| Monthly income net of tax | £33 | |

| Net rental yield after tax (on property value) | 0.23% | |

| Yield on investor’s captial (£50,000) after tax | 0.79% | |

| Annual income net of tax | £396 |

Some buy-to-let investors may dispute the numbers and it is acknowledged that rental yields can vary quite widely across the UK, but it is a reasonable insight that provides a framework for making better informed decisions. On these numbers, an investor with no mortgage would have received a net yield after tax of just over 2% on their capital7 – still below current inflation (Retail Prices Index).

What is interesting about the numbers in this example is that if the mortgage interest rate is raised by only 0.5% p.a., then the net yield after tax is near enough zero, before inflation. It is worth remembering that rents do not necessarily go up just because interest rates do. Those who lived through the property market slump of the early 1990s and interest rates of 15% (which I did) still remember the pain of having to find cash from their own earnings to cover mortgage payments on rented properties and of a prolonged period of negative equity. It took more than five years from the bottom of the market in 1993 to recover to the former peak, before inflation is taken into account. The geared buy-to-let investor in our example would have had to find £1,000 per month in 1991 to cover the rental shortfall to meet the costs and mortgage interest payments. Many were forced to sell, creating a downward spiral on prices.

Thinking like an investor

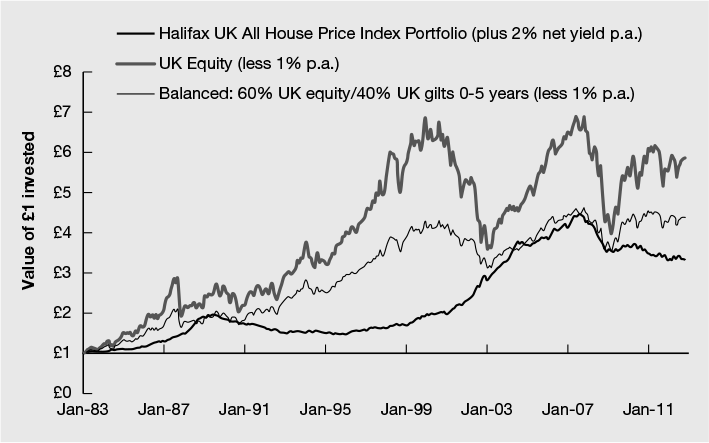

In many case, because the true net yield is so low, buy-to-let property is in effect a big punt which depends on price appreciation for its long-term success. A sensible investor will look at an asset class dispassionately and consistently, looking solely at neither yield nor capital gain, but on a total return basis being the combination of the two. To make a better informed comparison and to try to level out the playing field, if we generously assume a net post-tax yield of 2% on an ungeared buy-to-let investment and add this to the price return of the UK house price series, we can get a rough picture of how it has performed against other more traditional investment portfolios. Costs of 1% per annum have been deducted from the traditional portfolios for fairer comparison. No initial setup costs for the buy-to-let strategy have been deducted, even though these can be material. The outcome is illustrated in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Ungeared buy-to-let versus traditional portfolios – simulated strategies

Source: Albion Strategic.

As you can see, the ungeared buy-to-let simulation delivered strong returns during the equity market crash of 2000–2003 but suffered badly during the credit crisis. It was outperformed marginally by a typical equity/bond portfolio and materially by equities over the period. Looking at the worst case downsides of each portfolio, one can see that ungeared property is similar in risk to the ‘balanced’ portfolio (see Table 9.4). That is what one would expect from a hybrid asset class that derives regular income by way of rent, similar to a bond, but with the capital appreciation potential of equities. Borrowing 100% of the capital invested would double the downside risk to capital, making this approach comparable to equity investments.

Table 9.4 Downside risk – worst case returns over different horizons (after inflation)

Source: Data from Albion Strategic. Simulated returns as described in the note to Figure 9.1.

The role of residential property

One of the key problems with property, and one usually glossed over by investors when comparing it with a fully diversified investment portfolio, is that property is an illiquid asset class. If you want to realise your investment (and any accrued capital gains that will arise in a single tax year) you need to find someone else willing to buy it from you. Property, other than your home, has a place to play in your wider wealth plans, perhaps through an allocation to global commercial property as part of a well-balanced and diversified traditional investment fund, by way of some sort of collective investment scheme or even held directly as part of a self-invested pension plan. Currently residential property cannot be held in a pension plan.

Perhaps the biggest risk of the buy-to-let market is the concentration of risk in not just one narrow asset class – residential property – but in one house or flat, on one street in one town. This lack of diversification is an unattractive attribute for a plan to deliver wealth and happiness in retirement. It is difficult (indeed usually impossible) to rebalance a portfolio by selling part of the property should you wish to reduce your exposure to that asset without outright disposal.

Perhaps if you could build a large diversified portfolio of, say, 30 properties, or several large houses with multiple occupants (HMOs) like students, possibly with a dedicated property manager, you might be able to withstand the occasional negative cashflow on a small proportion of rental properties and derive economies of scale on running costs. But the reality is that most buy-to-let investors are on a small scale and have relied on capital gains to provide the bulk of their returns. Once those capital gains evaporate and negative cashflow kicks in, property equity can quickly be wiped out.

If you want to run a business and you have an interest in property then by all means invest in residential rental property, but make sure that you understand the significant risks you will be exposed to compared with the potential returns, that you can handle the lack of liquidity and the demands on your time, and that you do it on a big scale.

Residential development

One way to make high returns from residential property which is not to be used as your primary residence, and that is potentially much lower risk and more liquid, is to engage in either developing or redeveloping residential properties for immediate sale. Make no mistake, developing and/or redeveloping property of any type is a business first and an investment second, and it requires discipline, organisation and know-how to do well. Why developing/redeveloping has more appeal is because the tail-end risk inherent in rental properties (rent voids, interest rates rises, maintenance costs and stagnant rent) does not exist. The main risk is being able to sell the property, bank a profit and receive the cash proceeds to reinvest in another project.

An uplift of 18% on purchase price plus development costs seems a prudent basis on which to assess a project, but assuming this holds good, and the property market is stable (neither increasing nor decreasing in value), a pre-tax return of more than 10% seems entirely reasonable. If you become good at this, and manage to buy better-value properties with more upside and/or lower refurbishment costs, and the property is located in an up-and-coming area, you could do even better than this. But – and it’s a big but – there are many moving parts to a property development or redevelopment and it will need your constant attention.

Running a property development business also benefits from certain tax benefits, which might make it more appealing than a residential rental business (see Chapter 14). If you have the time and inclination, and don’t put all your capital into this activity, it could be a legitimate element of your wealth plan. But do remember that risk and return are related and you don’t generate returns in excess of 10% per annum without taking on a fair degree of risk, not all of which will be apparent at the outset.

At the time of writing, much of the UK residential property market has seen strong increases in values. I have no idea how this will turn out, but I do know that value is a product of affordability. With prices stretched, mortgage finance becoming harder to obtain (due to a mixture of new eligibility rules and tougher bank capital rules), house builders increasing supply and interest rates set to rise from the current historic low level, it doesn’t feel like the beginning of a gold rush to me.

Example property development transaction

| Purchase price of property | £300,000 (A) | |

| Stamp duty@ 3% | £9,000 | |

| Legal fees | £2,000 | |

| Refurbishment costs | £60,000 (B) | |

| Total costs | £371,000 (C) | |

| Selling price ((A + B) + 18%) | £424,800 (D) | |

| Selling costs@ 1.5% | (£6,400) | |

| Legal fees | (£2,000) | |

| Interest lost on capital @ 1.75% | (£6,500) | Assume £371,000 for 12 months |

| Total costs | £14,900 (E) | |

| Net proceeds (D–(C+E)) | £38,900 (F) | |

| Annual return F/C = 10.50% |

Agricultural property, farmland and woodlands

‘Buy land, they’re not making it anymore.’

Mark Twain

Farming is one of the world’s oldest businesses. The industry ranges from huge multinationals farming millions of acres down to smallholdings of a few acres. Activities include arable farming, livestock production, growing and harvesting timber, and conservation activity. Although the vast majority of owners of farms and agricultural property in the UK are farmers (50%), a significant proportion are owned by people who are not farmers (40%), with a much smaller proportion owned by institutions and companies (10%).8 The increase in ownership of farms and agricultural land by non-farmers has occurred mainly over the past ten years caused by a combination of factors, including:

- the perception of farms as a tangible ‘safe haven’ against the backdrop of the global credit crisis and volatile investment markets

- tax-efficient means of transferring wealth to the next generation

- a subsidy regime that provides attractive government-backed cashflows

- meets desired lifestyle and/or aspirational needs (trophy asset) of the individual

- conservation and environmental motivation.

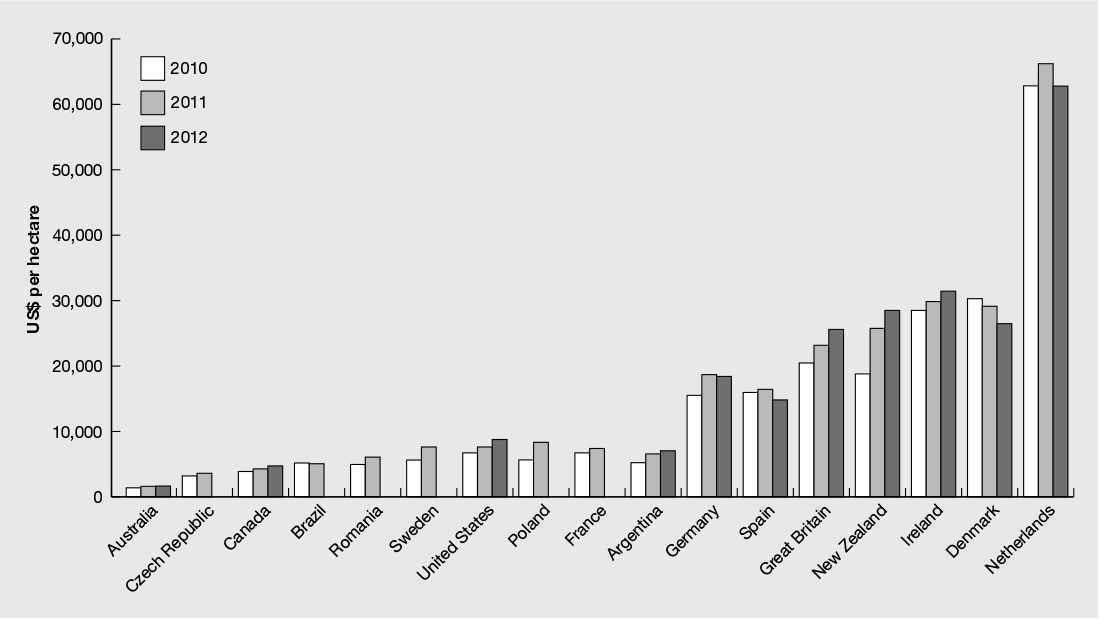

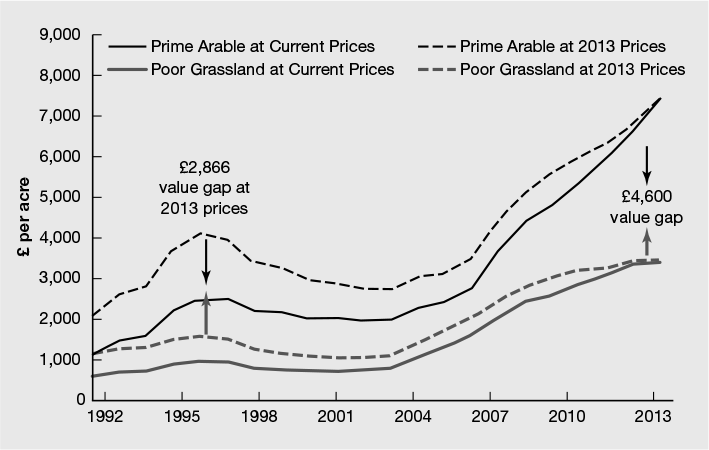

Figure 9.2 shows the price of land globally and how this has changed over the past few years, while Figure 9.3 illustrates the significant after-inflation increase in value of high- and low-grade UK farmland over the past 20 years. Farmland has certainly proven to be a very good investment over the past ten years or so, in the region of 20% p.a. for the world since 2002 and 13% p.a. for the UK. Over the ten years to 2013 the cumulative gains from UK farmland has been 273%, compared with 135% for prime residential property in central London.9

Property experts predict continued growth in asset values, in the region of 5–8% p.a. However, it’s important to bear in mind the risks associated with investment in this sector. These risks include:

- unpredictable maintenance costs

- illiquid asset

- agricultural subsidies may be reduced or stopped in the future

- if the land is not actively farmed this may lead to loss of tax benefits

- possible reduction in demand from non-farmer owners, as the world economy improves and competition for capital increases

- any borrowing used to fund the purchase needs to be serviced from rental income or farming profits and a rise in interest rates will alter the return profile and cashflow position

- rental income may depend on finding a successful farm tenant to farm the land

- if not to be let out, the land will need to be farmed by the owner as a farming business and all that that entails.

Figure 9.3 Average GB prime arable and poor grassland values adjusted for inflation

Source: Savills Research.

Unlike residential property, it is possible for a pension plan to invest in agricultural land and associated commercial properties, as long as this is done on full commercial terms.

Farms and agricultural land also benefit from attractive tax treatment, including in relation to inheritance tax, which makes them particularly attractive to wealthy families as a means of passing on family wealth to the next generation (see Chapter 14 on tax planning for an overview of these tax benefits). Unless you are very wealthy, buying agricultural land is likely to make sense only if this is part of your desired lifestyle (you want to run a smallholding) or wider business aspirations.

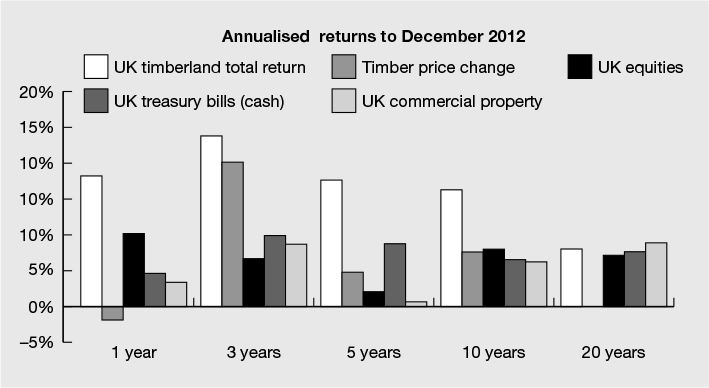

Commercial woodland

Commercial woodland is an alternative, tangible asset class, which benefits from generous tax treatment. Depending on the age and type of trees being grown, the trees can be harvested or sold standing, to generate cashflow from between 3 and 30 years or more. The benchmark index for UK commercial woodland performance is shown in Figure 9.4. On the basis of these figures commercial woodland appears to offer attractive investment returns, which are broadly similar to other asset classes over the longer term.

Figure 9.4 UK timberland performance 1993–2012

Source: Data from Forestry Commission Nominal Price Index of Coniferous Standing Sales (for Great Britain), FTSE All-Share Index, FTSE UK Gilts Index 5–15 yrs, IPD UK Annual Property Index.

Woodland covers about 3.1 million hectares or about 13% of the UK, with 60% being privately owned and the balance owned by the Forestry Commission. Interestingly, the Domesday Book in 1086 noted that 15% of England was covered by woodland, but this fell to a low of 5% for the UK just after the Second World War. The trend is that UK woodland cover is increasing year on year and 13,000 hectares of new woodland were planted in 2012.10

However, it should be noted that this index is calculated from a small sample of about 150 private-sector coniferous plantations of predominantly Sitka spruce in mainland Britain, with a value of £220 million. It is not, therefore, a statistically robust basis on which to determine the investment characteristics of woodland. There appears to be a significant regional variation in the value of woodlands. The split between the value of the land and timber is typically about 20% and 80% respectively.

The economic rationale for investment in commercial woodland (environmental, sustainable fuel, rising demand for timber products and lack of supply) certainly seems compelling, but the following commentary on the history of UK commercial woodland values over the past 15 years reminds us that values can fall substantially as well as rise:

‘Between the late 1990s and mid-2000s, forestry property values fell in response to timber price falls and strengthening of sterling against the US dollar and Swedish kroner. UK-grown timber products experienced high levels of competition from unsustainable levels of timber imports from the Baltic States. Timber prices fell by over 70%. From 2004, forestry returns recovered. Inward capital investment in timber processing and infrastructure impacted on efficiencies; sterling weakened; timber prices increased; whilst global demand from the Far East impacted commodity supplies generally. From the late 2000s the incentives to use wood as an energy source have helped move timber prices to new levels. At the same time, land-based assets have provided an alternative home for cash deposits in times of low interest rates and for investors in general seeking less volatile markets.’11

Notwithstanding the return potential, commercial woodland also benefits from the availability of subsidies and generous tax treatment. Each year there are usually a number of grants available to help landowners fund the cost of creating a woodland plan and establishing new woodlands and/or improving existing ones, which meet certain government environmental objectives. These grants vary from £10 to £20 per hectare for planning work, and 50% to 80% of establishment and maintenance costs. In addition, the income from harvesting woodland is exempt from personal or corporation tax, as is any capital gains arising on the sale of the trees (but not the land). After two years of ownership, the value of the timber (but not the land it sits on) is exempt from inheritance tax.

However, there are numerous risks and ongoing maintenance costs associated with woodlands, which should not be underestimated. Storm damage, diseases (such as the recent Ash Dieback) and government regulations can wipe out much of the financial returns on offer, although insurance can help mitigate these to a degree. If you are not thinking of engaging in commercial forestry as part of a new or existing farming business, and don’t want to spend lots of time managing the investment, but you still wish to invest in it for the tax and return benefits, there are two main options open to you:

- Management service – where you have at least £1 million to invest directly into commercial woodland, you could use the services of a specialist investment adviser, who will help with investment selection, management supervision, financial control, valuations, annual report and accounts, VAT administration, insurance, timber marketing, property realisation, and research and performance measurement. Clearly, the professional fees will reduce your overall return, but at least it removes much of the hassle involved with direct investment.

- Woodland fund – where you wish to invest more modest amounts into commercial woodland, you can invest in an unregulated fund that provides all the benefits of direct ownership, including the various tax breaks, together with the economies of scale and geographic diversification associated with larger investments. Additionally, once investment is made into the fund, investors are not liable for further capital calls.

My own view is that commercial woodland does offer a highly tax-efficient, established and non-aggressive means of passing on wealth to future generations. Where inheritance tax and/or capital gains tax deferment is a concern and investment in a tangible asset is preferred to a trading business and/or other simpler IHT planning has already been done, commercial woodland, either direct or via a fund, offers a useful means to achieve this. As long as you choose wisely, don’t put too much of your wealth in it, and understand the risks and rewards, it might form part of your overall wealth-planning strategy.

1 Source: this is the average of the UK average rental property yield quoted by Countrywide (6.1%) and LSL Property Services plc (5.2%) in their annual rental property index reports in January 2014.

2 Source: Countrywide: ‘Annual lettings index,’ January 2014 shows Scotland has the highest average yield of 6.6% and Central London has the lowest yield of 4.8%. Clearly within these averages there will be further variations.

3 Source: LSL Property Services plc press release February 2014, www.lslps.co.uk/documents/buy_to_let_index_jan14.pdf

4 This is the average of the UK average rental property yield/monthly rent quoted by Countrywide (6.1%/£854) and LSL Property Services plc (5.2%/£742) in their annual rental property index reports in January 2014.

5 For example, UKpropertyexpert.com: ‘£250 per month per property. The real cost of buy-to-let?’

6 Ideally, investors should calculate the internal rate of return that any buy-to-let property opportunity could deliver from all of the cashflows involved to see where the risks and return truly lie.

7 Tax rates may be lower than 40%, e.g. achieved by owning the property in a partner’s name whose total income falls within a lower tax band. Net yields after tax would thus be a little higher.

8 Source: Savills World Research, Market Survey – UK Agricultural Land 2014.

9 Ibid.

10 Source: Forestry Commission website, accessed April 2014.

11 IPD UK Annual Forestry Index factsheet 2012.