The Crucial Prerequisite: Know What You Want

When you are faced with tricky commercial negotiations, you really must know how to establish your priorities and set your objectives. Here are a few practical tips to help you.

Prepare the Ground

This involves identifying all the components of the agreement that you are seeking and that may be negotiated. Generally the agreement will need to specify the following:

- Logistical factors: schedules, deadlines, transport, organization

- Technical factors: product and service specifications (main and secondary products/services)

- Legal factors: the nature of reciprocal undertakings, terms and conditions applicable in the event of subsequent disputes

- Financial factors: price but also method and terms of payment

- Commercial factors

It is important to take a broad view of the agreement in order to properly identify the principal aspects that are at stake as well as to anticipate additional issues that could be involved in the negotiations with your customer.

Rank Your Priorities

As we shall see in detail in a later chapter, you need to understand what the other party “really wants”: her true priorities, her major concerns, and her essential objectives. Likewise, you must analyze what is at stake in the negotiations for your own business: What, above all, are you seeking to achieve?

For a seller, one set of negotiations may be particularly important for the volumes that the deal will generate, another may be crucial because the deal will help the business develop fresh expertise, while another may help the business gain a foothold in a growth market. Indeed, protecting price levels is not generally a priority per se. When the seller wants to protect her price, she may have several very different priorities.

If her priority is to ensure that the contract is profitable, protecting price levels is not the only potential strategy. Depending on what the customer “really wants,” the seller may prefer to agree to a small price reduction offset by, for example,

- generating a much larger sales volume,

- identifying compensatory measures that generate savings (grouping orders and deliveries, simplification of a product or packaging).

If her priority is to avoid any “slippage” in the market and ensure the protection of a benchmark price levied on all customers, she may refuse to make any concessions on price but may, if necessary, grant her customer nonprice concessions such as cooperation agreements or extra services.

For a buyer, properly defining priorities is even more important, as you usually have a choice from among several suppliers who meet expectations to varying degrees. This can be difficult to achieve because there is a risk that unpleasant and unforeseeable surprises will arise during the purchasing process, and these are, by definition, almost impossible to assess in advance.

Particularly in diplomacy, excellent negotiators are characterized by their seeming flexibility on certain secondary issues as a counterweight to absolute firmness on key issues. It is therefore essential to know what the true priorities are—both the other party’s and your own. If everything is a priority, then you have no true priorities!

Ask yourself these questions:

- What is really important for me in these negotiations?

- What will enable me to say, a year from now, that I negotiated well today?

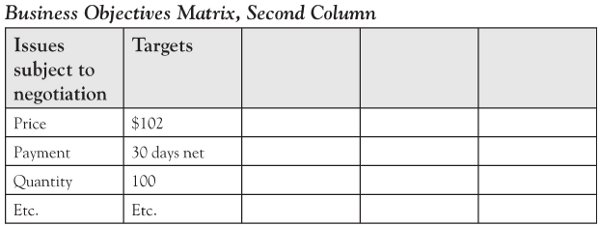

Do Not Make Do With a Price Range: Specify Precise Objectives

The Roman philosopher Seneca said, “There is no such thing as a favorable wind for those that do not know where they are going.” Thus, for each element of your proposal (price, volume, deadlines, etc.), you need to define precisely the figures you seek.

For the seller, this definition of objectives must be undertaken well before the offer is presented to the customer. This is a crucial point and the source of many errors in practice: Too often, the seller starts by making an offer, and only when faced with pressure from the customer does the seller wonder what he needs to achieve and where he can give ground. You need to reverse this logic and define precise objectives before you do anything else.

In certain sectors there is a tradition of laying out a suitable product or service offer according to the customer’s budget. Here we shall address the most common instance of this, the one where the supplier starts by establishing the product or service offer according to the customer’s needs—and then the price. For businesses selling simple, standardized, or commonplace products, the price may be determined by two criteria: production cost and knowledge of the prices charged by competitors.

Where more complex products or services are being sold, the price may also include the “perceived value” compared with competitors. For this, you need to identify your main competitors and collect and analyze as much objective data as possible to allow you to calculate

- the probable offer price level,

- the main strengths and weaknesses of that offer compared to the one that you are compiling.

It is then a case of quantifying the value of each relative advantage of your offer, as perceived by the customer. For example, during a particular set of negotiations, you might believe that a technical solution that can be implemented 2 months earlier might represent a perceptible advantage for the customer, amounting to some $200,000.

Likewise, you can quantify the perceived cost of each relative disadvantage of your offer compared with that of your main competitor.

Lastly, account needs to be taken of the “value added” that your customer may attach to one or other supplier for reasons of trust, perception, or relationship. The “perceived value” of the offer is therefore

estimated price of the leading competitor + estimated value of our offer’s relative advantages – estimated cost of our offer’s relative disadvantages ± difference in “value added.”

Naturally this “perceived value” plays only an indicative role. It must be compared with recorded market prices and with the business’s average selling price for comparable products or services in order to enable you to define your target price. You also need to study production costs thoroughly and examine the profitability of the transaction if it is completed at the “target” price.

A buyer also needs to define precise objectives. It is true that it is generally up to the seller to “reveal her hand” first. Furthermore, the objectives may also change depending on the information gleaned during negotiations (e.g., the appearance of new offers even more attractive than those anticipated). Yet knowing what you want is one of the keys to negotiating both a purchase and a sale.

Above all, you need to assess the overall consistency of negotiating objectives: Taking account of the other party and his expectations and considering the market, production costs, and your business’s policies, are your targets acceptable? Are they realistic? Do they form a consistent whole?

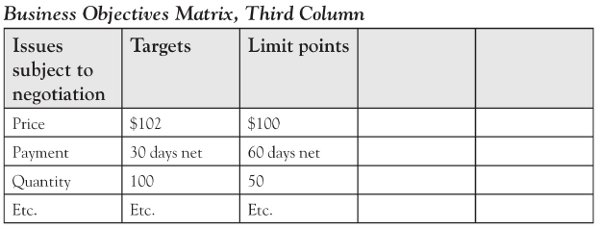

Do Not Confuse Targets With the Limit Points

Prepare yourself for the worst, including market conditions that are less favorable than anticipated and even stronger pressure than expected from your counterpart for terms lower than your specified targets. It is essential that you are clear about your limit points (commonly known as your bottom line). If you are not, you run the risk of agreeing to concessions in the heat of the moment that you will later regret. Thus, for each element of your offer, you need to determine acceptable limit points by calculating, if possible, the cost of concessions envisaged (resulting from the difference between the target set and the limit points).

For certain items, at this stage there may be a need to anticipate “terms of access to limit points.” For example, a seller may need to sell a certain product volume in order to agree to a particular price level below the target price. A buyer may anticipate concessions on the purchase price, provided that the contract comes with extra guarantees.

Naturally, since buyers are “obliged to settle” with one or another of their potential suppliers, it is more difficult for them to set their own absolute limit points. They must set barriers beyond which they will not allow themselves to go, at least until such time as they have exhausted all other negotiating options.

At this stage you have prepared the ground (all those items subject to negotiation), ranked what is at stake (priorities and risks), determined your negotiating objectives, and clarified your limit points.