What Are Your Opponent’s Intrinsic Powers?

Intrinsic Negotiating Power: The Seven “Cursors of Power”

“Intrinsic power” is an objective strategic factor over which we have little control. In negotiations, you need to be able to analyze this power so as to take it into account when you calibrate the level of your demands. According to Roger Fisher and William Ury of the Harvard Negotiation Project, the intrinsic power of each negotiator resides almost solely in the quality of her best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA)—namely, her “best fallback solution” if negotiations should fail. Everything else is considered to be secondary.

We can identify seven strategic power factors in negotiations.

The Power of Size

The customer possesses significant intrinsic power if his purchases account for a large proportion of the seller’s turnover. This factor is important especially if the supplier’s cost structure includes a significant proportion of fixed costs. In contrast, the supplier has the power of size at his disposal if the customer accounts for only a tiny proportion of his sales.

The Power of Choice

As Fisher and Ury have demonstrated, the stronger negotiating party is the one with the best BATNA. In other words, that party enjoys the option of being able to rely on a satisfactory fallback solution if the negotiations fail.

The customer possesses great intrinsic power if she can easily obtain an equivalent product or service to that being offered by the supplier. She may enjoy that power either because the products in question are undifferentiated or standardized or because the customer has the option to produce the product or service in-house. This is the case with many services (development of information technology [IT] programs, recruitment, but also cleaning or maintenance) and with certain products, particularly in the subcontract automotive sector.

However, this power of choice is only effective if the switching costs are low. These are the costs that customers incur by changing their supplier: changes in equipment, user training, the learning curve, and so on. Such costs can be high and can reduce the buyer’s power.

The supplier only possesses the power of choice if demand potentially exceeds supply. This includes circumstances in which products are not fully comparable (e.g., a unique real estate site, an expert service, etc.).

The Power of Information

This power is at the disposal of a customer who is fully informed about the products and the market; for example, information concerning the technical “pluses” and “minuses” of each potential supplier, market prices, or each supplier’s current constraints. However, that power is also at the disposal of sellers who are aware of their customers’ constraints; for example, information concerning competitors’ prices, the weak points of other suppliers’ products or services, or the decision-making processes and pressures exerted on buyers within their own organization.

The Power of Influence

Some customers possess the power of influence, either within their own industry or with end customers in the case of distribution companies. Some sellers enjoy this power of influence when they have the ear of particular managers who are capable of influencing decisions.

The Power of Time

A customer who has sufficient time to research all the options, to interrupt negotiations, and to seek new solutions is a customer with considerable power. A seller may also possess the power of time if unconstrained by looming deadlines. In negotiations, if you have to conclude by a particular date, the other party merely has to wait.

The Power of Sanction

A customer who possesses the means of penalizing a supplier enjoys greater power. The sanction may be positive (providing new opportunities) or negative (delaying payment of an invoice or canceling a deal). This analysis sheds some light on the purchasing strategies of major corporations. Those strategies are essentially designed to

- reduce the number of suppliers (power of size),

- seek out or even encourage new sources of supply (power of choice),

- encourage the standardization of products (power of choice),

- avoid any situation where they depend on a single supplier (powers of choice, information, and endorsement),

- collect data (power of information; e.g., entertaining salespeople, participating in trade fairs).

More rarely, a seller may possess the power of sanction, but this only applies where the customer is (at least fleetingly) dependent on the supplier’s products, services, or expertise.

The Power of Legitimacy

Whether it is the seller or the buyer, a party making an apparently legitimate demand possesses a considerable asset. The legitimacy of a request may arise from a commitment given, a custom established, a law, or simply common sense and ethics. Indeed, someone who opposes a legitimate demand knows that he will probably face problems if this issue is brought to the attention of a third party.

The Propensity of a Negotiator to Use Her Power

A buyer has a strong propensity to exercise her power under the following circumstances:

- The product purchased represents a large proportion of the customer’s costs.

- The choice of product is not of strategic importance to the customer.

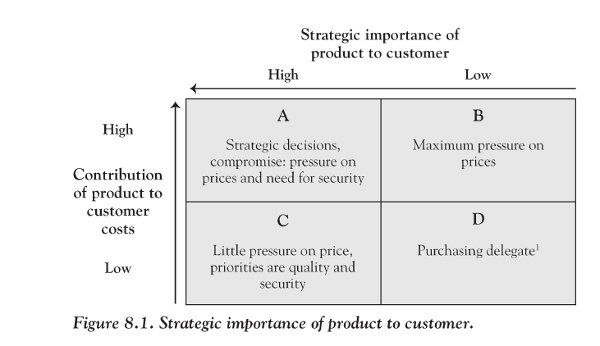

By combining these two factors (see Figure 8.1), you can get a clear idea of her likely purchasing strategy.

Examples of products of strategic importance include the following:

° Products whose absence could cause major losses (e.g., certain monitoring equipment)

° Products that may yield significant savings (e.g., oil detection products)

° Products that may yield significant gains (e.g., consultancy services with a view to an acquisition)

° Products influencing the quality or perception of the customer’s product (e.g., key part of a car engine)

In your view, where on this matrix would your customer put his negotiations with you?

- The customer is suffering from low profitability. This is a paradox: You might think that a company is profitable precisely because it buys at a lower price. Yet research proves that the most profitable corporations tend to pay a higher price for an identical product.

- The role of the purchasing decision maker is profit focused. An SME buyer or boss will often be more price sensitive than the production or IT manager, who will have a greater commitment to quality.

- The decision maker is very keen to meet targets on purchasing price and terms either through personal temperament or because he is committed to meeting that target, be that a personal commitment or a commitment to his organization.

For their part, sellers have a propensity to use their power if they see the potential for a major short-term gain without significant long-term consequences.

Figure 8.1. Strategic importance of product to customer.