The Secret of the Expert Negotiator

You are the head of government of a rich country. Your car industry exports 50,000 vehicles per year to a neighboring country, while your domestic market imports virtually no cars from that country. For you, it is important to maintain export levels. The head of government of that neighboring country suddenly demands a 30% reduction in your car sales in his market. How should you respond?

You could tough it out, refusing to make any concessions while threatening commercial reprisals. You could enter into negotiations to reach a compromise, for example, by offering to reduce your exports by just 5%. However, you could also use every possible means to identify your counterpart’s “real demands.” Indeed, while his “apparent demand” might be a 30% reduction in car imports, his “real demands” might be, for example,

- to keep in his country those manufacturing plants that could potentially be relocated elsewhere by carmakers;

- to obtain better access to your national market for his own car exporters;

- to be shown greater recognition and respect by your government ahead of forthcoming negotiations over trade in fruits and vegetables;

- to gain your support in a campaign for international aid;

- to show his people, a few months before upcoming elections, that he will not allow his country to be pushed around by its neighbors;

- to “block the path” of one of the leaders of the parliamentary opposition who is encroaching on his political territory.

Depending on the real demands of this head of government, you can devise an appropriate strategy, one that may very well allow you to maintain or even increase your car exports.

When your counterpart demands a concession from you, he is thereby making an “apparent demand.” The reason why he is demanding that concession allows you to identify his “real demands.” It is often possible to seal a deal without giving in to his “apparent demand.”

In the business environment, what are the “real demands” that you might uncover?

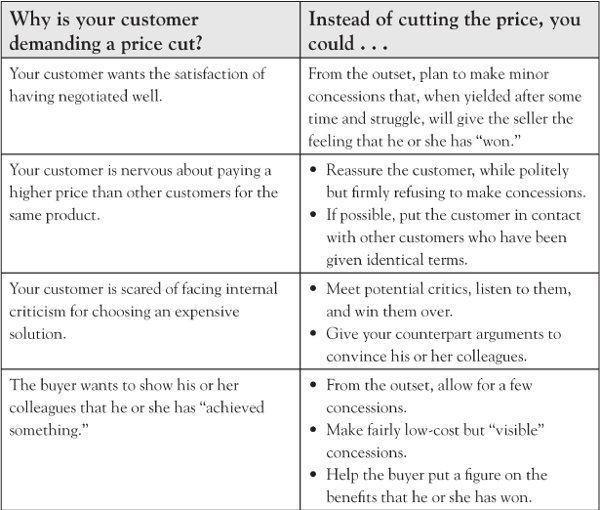

If you are a seller, here are a few examples of customers’ real demands:

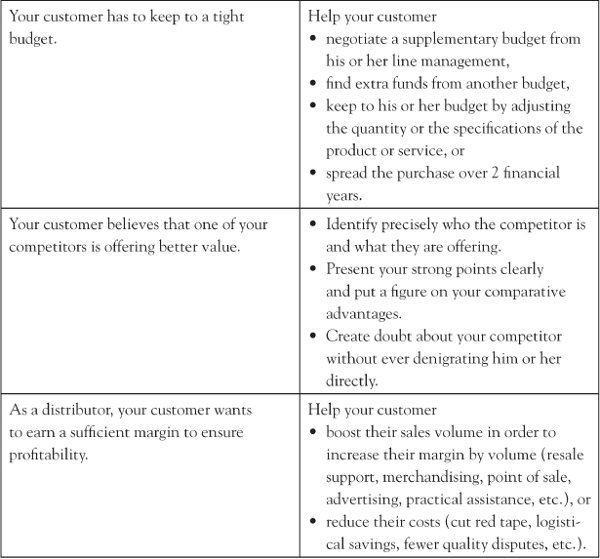

If you are a buyer, here are a few examples of sellers’ real demands:

Here are three recommendations to enable you to move beyond a customer’s apparent demand so as to identify his real expectations:

Treat Your Counterpart Sympathetically

By demanding a price cut, your counterpart is attacking you. She is questioning the quality of your proposal and doubting the validity of your arguments. Her tone may sometimes be abrupt, her attitude offhand, and her explanations vague. She may go so far as to dictate “take it or leave it” conditions.

Our natural tendency is to resist, whereas it should be to listen. Instead of fighting back, we should try to understand.

Indeed, whether or not she is acting in good faith, your counterpart always adopts the behavior that she believes to be necessary. Therefore there is nothing to be gained from judging her behavior. On the contrary, to be effective requires that you treat your counterpart sympathetically. In this way, you will be able to calmly identify the reasons why she is behaving in this way and making such a demand.

Never View the Other Party’s Initial Demand as a Basis for Discussion

If they are good negotiators, customers always begin by making an excessive demand: for example, asking for a 10% discount when they are hoping for 5% and the seller can only allow 3%. If the seller takes account of the customer’s initial demand (even just by repeating it: “You want to obtain a 10% discount”), he gives credibility to the buyer’s demand and encourages him to pursue it tenaciously. As the negotiations progress, constant reference will be made to the “10%” quoted by the buyer, even though that figure may have been quite arbitrary and the customer’s real concerns may lie elsewhere.

In contrast, if you reformulate the principle of the other party’s demand while playing it down (e.g., by merely saying, “so you want to reexamine the pricing issue”), you remain free to control the discussion and seek out your counterpart’s “real demands.”

Ask Open Questions

When faced with another party’s initial demand as she “enters into negotiations,” asking questions does not come naturally. Indeed, you may fear that your counterpart will present convincing arguments, perhaps quoting deals on offers from competitors or occasionally using dirty tricks with the sole aim of consolidating her position and putting you in a difficult situation. Thus the questions that are posed at this particular moment are often too tentative and focus on confirming the demand: Is our counterpart sure she can obtain contracts at such a price?

On the contrary, you need to pose open questions about the reasons for the demand, starting from the principle that even if the opposing party’s demand is excessive, her motives are certainly legitimate. Having reformulated the principle of the demand while playing it down, it can be useful to ask some open questions: “So you wish to look at pricing again. How would that help you?” “Apart from the price itself, what is the most important issue for you?”