IN CONTEXT

Democracy

Political virtue

431 BCE Athenian statesman Pericles states that democracy provides equal justice for all.

c.380–360 BCE In the Republic, Plato advocates rule by “philosopher kings,” who possess wisdom.

13th century Thomas Aquinas incorporates Aristotle’s ideas into Christian doctrine.

c.1300 Giles of Rome stresses the importance of the rule of law to living in a civil society.

1651 Thomas Hobbes proposes a social contract to prevent man from living in a “brutish” state of nature.

Ancient Greece was not a unified nation-state as we would recognize one today, but a collection of independent regional states with cities at their center. Each city-state, or polis, had its own constitutional organization: some, such as Macedon, were ruled by a monarch, while others, most notably Athens, had a form of democracy in which at least some of the citizens could participate in their government.

Aristotle, who was brought up in Macedon and studied in Athens, was well acquainted with the concept of the polis and its various interpretations, and his analytical mind made him well qualified to examine the merits of the city-state. He also spent some time in Ionia classifying animals and plants according to their characteristics. He was later to apply these skills of categorization to ethics and politics, which he saw as both natural and practical sciences. Unlike his mentor, Plato, Aristotle believed that knowledge was acquired through observation rather than intellectual reasoning, and that the science of politics should be based on empirical data, organized in the same way as the taxonomy of the natural world.

Naturally social

Aristotle observed that humans have a natural tendency to form social units: individuals come together to form households, households to form villages, and villages to form cities. Just as some animals—such as bees or cattle—are distinguished by their disposition to live in colonies or herds, humans are by nature social. Just as he might define a wolf by saying it is by nature a pack animal, Aristotle says that “Man is by nature a political animal.” By this, Aristotle means simply that Man is an animal whose nature it is to live socially in a polis; he is not implying a natural tendency towards political activity in the modern sense of the word.

The idea that we have a tendency to live in large civil communities might seem relatively unenlightening today, but it is important to recognize that Aristotle is explicitly stating that the polis is just as much a creation of nature as an ants’ nest. For him, it is inconceivable that humans can live in any other way. This contrasts markedly with ideas of civil society as an artificial construct that has taken us out of an uncivilized “state of nature”—something Aristotle would not have understood. Anyone living outside a polis, he believed, was not human—he must be either superior to men (that is, a god) or inferior to them (that is, a beast).

The good life

This idea of the polis as a natural phenomenon rather than a man-made one underpins Aristotle’s ideas about ethics and the politics of the city-state. From his study of the natural world, he gained a notion that everything that exists has an aim or a purpose, and he decided that for humans, this is to lead a “good life.” Aristotle takes this to mean the pursuit of virtues, such as justice, goodness, and beauty. The purpose of the polis, then, is to enable us to live according to these virtues. The ancient Greeks saw the structure of the state—which enables people to live together and protects the property and liberty of its citizens—as a means to the end of virtue.

"Law is order, and good law is good order."

Aristotle

Aristotle identified various “species” and “sub-species” within the polis. He found that what distinguishes man from the other animals is his innate powers of reason and the faculty of speech, which give him a unique ability to form social groups and set up communities and partnerships. Within the community of a polis, the citizens develop an organization that ensures the security, economic stability, and justice of the state; not by imposing any form of social contract, but because it is in their nature to do so. For Aristotle, the different ways of organizing the life of the polis exist not so that people can live together (since they do this by their very nature), but so that they can live well. How well they succeed in achieving this goal, he observes, depends on the type of government they choose.

In ancient Athens, citizens debated political affairs at a stone dais called the Pnyx. To Aristotle, the active participation of citizens in government was essential for a healthy society.

Species of rule

An inveterate classifier of data, Aristotle devised a comprehensive taxonomy of the natural world, and in his later works, especially Politics, he set about applying the same methodical skills to systems of government. While Plato had reasoned theoretically about the ideal form of government, Aristotle chose to examine existing regimes to analyze their strengths and weaknesses. To do this, he asked two simple questions: who rules, and on whose behalf do they rule?

In answer to the first question, Aristotle observes that there are basically three types of rule: by a single person, by a select few, or by many. And in answer to the second question, the rule could be either on behalf of the population as a whole, which he considered true or good government, or in the self-interest of the ruler or ruling class, a defective form of government. In all, he identified six “species” of rule, which came in pairs. Monarchy is rule by an individual on behalf of all; rule by an individual in his own interests, or tyranny, is corrupted monarchy. Rule by aristocracy (which to the Greeks meant rule by the best, rather than rule by hereditary noble families) is rule by a few for the good of all; rule by a self-interested few, or oligarchy, is its corrupted form. Finally, polity is rule by the many for the benefit of all. Aristotle saw democracy as the corrupted form of this last form of rule, as in practice it entails ruling on behalf of the many, rather than every single individual.

"The basis of a democratic state is liberty."

Aristotle

Aristotle argues that the self-interest inherent in the defective forms of government leads to inequality and injustice. This translates into instability, which threatens the role of the state and its ability to encourage virtuous living. In practice, however, the city-states he studied did not all fall neatly into just one category, but exhibited characteristics from the various types.

Although Aristotle had a tendency to view the polis as a single “organism,” of which the citizens are merely a part, he also examined the role of the individual within the city-state. Again, he stresses Man’s natural inclination to social interaction, and defines the citizen as one who shares in the structure of the civil community, not merely by electing representatives, but through active participation. When this participation is within a “good” form of government (monarchy, aristocracy, or polity), it fosters the ability of the citizen to lead a virtuous life. Under a “defective” regime (tyranny, oligarchy, or democracy), the citizen becomes involved with the self-interested pursuits of the ruler or ruling class—the tyrant’s pursuit of power, the oligarchs’ thirst for wealth, or the democrats’ search for freedom. Of all the possible regimes, Aristotle concludes, polity provides the best opportunity to lead a good life. Although Aristotle categorizes democracy as a “defective” form of regime, he argues that it is only second best to polity, and better than the “good” aristocracy or monarchy. While the individual citizen may not have the wisdom and virtue of a good ruler, collectively “the many” may prove to be better rulers than “the one.”

The detailed description and analysis of the Classical Greek polis seems on the face of it to have little relevance to the nation-states that followed, but Aristotle’s ideas had a growing influence on European political thought throughout the Middle Ages. Despite being criticized for his often authoritarian standpoint (and his defense of slavery and the inferior status of women), his arguments in favor of constitutional government anticipate ideas that emerged in the Enlightenment.

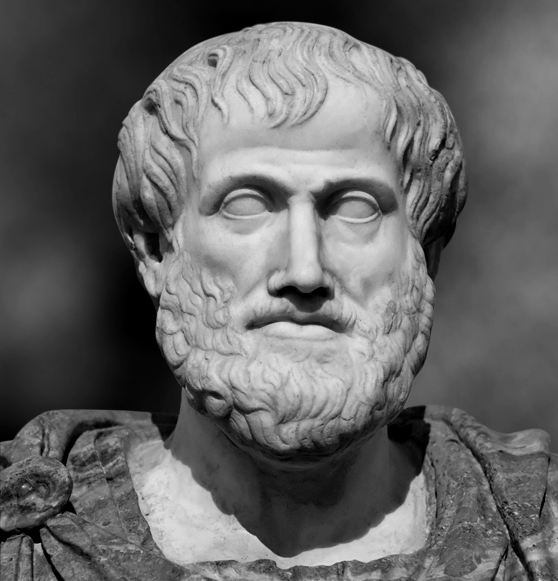

ARISTOTLE

The son of a physician to the royal family of Macedon, Aristotle was born in Stagira, Chalcidice, in the northeast of modern Greece. He was sent to Athens at 17 to study with Plato at the Academy, and remained there until Plato’s death 20 years later. Surprisingly, Aristotle was not appointed Plato’s successor to lead the Academy. He moved to Ionia, where he made a study of wildlife, until he was invited by Philip of Macedon to be tutor to the young Alexander the Great.

Aristotle returned to Athens in 335 BCE to establish a rival school to the Academy, at the Lyceum. While teaching there, he formalized his ideas on the sciences, philosophy, and politics, compiling a large volume of writings, of which few have survived. After the death of Alexander in 323 BCE, anti-Macedonian feeling in Athens prompted him to leave the city for Euboea, where he died the following year.

Key works

c.350 BCE

Nicomachean Ethics

Politics

Rhetoric

See also: Plato • Cicero • Thomas Aquinas • Giles of Rome • Thomas Hobbes • Jean-Jacques Rousseau