IN CONTEXT

Republicanism

Universal male suffrage

508 BCE Democracy in Athens gives all male citizens a vote.

1647 A radical part of Oliver Cromwell’s New Model Army calls for universal male suffrage and an end to monarchy.

1762 Jean-Jacques Rousseau publishes The Social Contract, arguing that sovereignty lies with the whole people.

1839–48 Chartism, a mass movement in Britain, calls for universal male suffrage.

1871 A newly united German empire grants universal male suffrage.

1917–19 As World War I ends, democratic republics replace monarchies across Europe.

The English Revolution, which reached the peak of its radicalism with the trial and execution of King Charles I in 1649, had fizzled out by the end of the 17th century. The “Glorious Revolution” of 1688 had seen the restoration of the monarchy, now subordinate to Parliament, and the stabilization of the British state. No formal constitution was written, and the brief experiment with a republic under Oliver Cromwell was over. The new government was a hybrid made of a corrupt and unrepresentative Lower House in the Commons, a corrupt and unelected Upper House in the Lords, and a monarch who was still nominally head of state.

The 1689 Bill of Rights that set out the parameters for the new government was a compromise that satisfied few, least of all those most obviously excluded from it: the Irish, Catholics, and non-conformists; the poor and the artisans; even the more prosperous middle classes and employees of the state. It was from this milieu that Thomas Paine emerged, after emigrating to America in 1774. In a series of incendiary and wildly popular pamphlets, he sought to reclaim arguments for democracy and republicanism that had been made during Cromwell’s time.

The case for democracy

In Common Sense, published anonymously in Philadelphia in 1776, Paine made the case for a radical break by Britain’s North American colonists from both the British empire and constitutional monarchy. Like Hobbes and Rousseau before him, he argued that people come to form natural attachments to each other, creating a society from individuals. As these attachments of family, friendship, or trade become more complex, they in turn create a need for regulation. These regulations are systematized into laws, and a government is erected to create and enforce those laws. These laws are intended to act for the people, but there are too many people to make collective decisions. Democracy is required, to elect representatives.

"When we are planning for posterity, we ought to remember that virtue is not hereditary."

Thomas Paine

Democracy, Paine held, was the most natural way to balance the needs of society with those of government. Voting would act as the regulating instrument between society and government, allowing society to shape government so that it more closely corresponded to social needs. Institutions such as monarchy were unnatural, since the hereditary principle stood apart from society as a whole, and monarchs could act in their own interests. Even a mixed state with a constitutional monarchy, as advocated by John Locke, would be dangerous, since a monarch could easily obtain more power and circumvent laws. Paine believed it was better to do away with the monarch entirely.

It followed that America’s best course of action in its war with the British empire was to refuse any compromise on the issue of the monarchy. Only with full independence could a democratic society be built. Paine’s clear and unequivocal call for a democratic republic was an immediate success in the midst of the Revolutionary War against the British empire. Returning to England in 1787, he visited France two years later, and became a firm supporter of the French Revolution.

The inattentive judges in William Hogarth’s satirical The Bench (1758) are portrayed as members of an idle, incompetent, and venal judiciary that has little regard for society’s rights.

Reflections on revolution

On returning from France, Paine had a rude awakening. Edmund Burke, a politician and one of the founders of modern conservative thought, had strongly supported the rights of American colonies to independence. Burke and Paine had been on friendly terms since Paine’s arrival back in England, but Burke had ferociously denounced the French Revolution, claiming in his 1790 Reflections on the Revolution in France that by its radicalism it threatened the very order of society. Burke viewed society as an organic whole, not amenable to sudden change. The American Revolution and Britain’s “Glorious Revolution” did not directly threaten long-established rights, but merely corrected some clear deformities in the system. In particular, they did not threaten the rights of property. But the situation in France, with its violent overthrow of the ancien regime, was clearly different.

Burke’s opposition caused Paine to defend his position. He replied with The Rights of Man, printed in early 1791. Despite official censorship, it became the best-known and widest-circulated of all English defenses of the revolution in France. Paine argued for the rights of every generation to remake its political and social institutions as it saw fit, not bound by existing authority. A hereditary monarch had no claim to superiority over this right. Rights, not property, were the only hereditary principle, transmitted across the generations. A second part to the pamphlet, published in 1792, argued for a major program of social welfare. By the end of the year, the two volumes had sold 200,000 copies.

The French National Assembly has its roots in the French Revolution’s National Convention, which was the country’s first governing assembly to be elected by universal male suffrage.

An end to monarchy

Under threat of prosecution, and with “Church and King” mobs burning his figure in effigy, Paine offered a still more radical step. His Letter Addressed to the Addressers on the Late Proclamation was written against “the numerous rotten boroughs and corporation addresses” that had published the royal proclamation against “seditious libel”—the writing and printing of texts that attacked the state. Paine, denouncing this and other abuses as a new tyranny, called for an elected National Convention to draft a new, republican constitution for England. This was a direct call for revolution in all but name, taking France’s republican National Convention as its model. Paine had returned to France shortly before the Address was published, and in his absence was found guilty of seditious libel.

The argument in the Address is brief, but tackles Burke head on. Although England’s Bill of Rights of 1689 gave guarantees about the rights all subjects would enjoy in a constitutional monarchy, it was open to abuse. Paine detailed some of the most obnoxious instances of corruption, but he wanted to go further and tackle the system itself. By defending hereditary property as the supreme law, this system drove the corruption and abuse. The tyranny of William Pitt’s government was a direct result of its defense of property. At the top of the regime was a hereditary monarch, and Parliament acted merely as a defense of Crown and property. Reform of the corrupt Parliament was not enough: the whole system had to be transformed, from the top down.

Universal male suffrage

Paine asserted that sovereignty should not lie with the monarch, but with the people, who have an absolute right to make or unmake laws and governments as they see fit. The existing system contained no mechanism to allow the people to change the government. It was therefore necessary, Paine argued, to sidestep the system by electing a new assembly—a National Convention, as in France.

"It will always be found, that when the rich protect the rights of the poor, the poor will protect the property of the rich."

Thomas Paine

Paine attempted to popularize an argument made by Rousseau: that the “general will” of the people should be sovereign in a nation, and that with transparent and fair elections to the Convention, private interests and corrupt practices would be squeezed out. Universal male suffrage would determine the delegates to the Convention, and these delegates would be charged with drafting a new constitution for Britain. It was England’s property qualification for voting that Paine held most responsible for the corruption and venality of the electoral system. Only in a system where the rights of both rich and poor were equally considered would each respect the other, and neither seek to rob the other.

A legacy for reform

Paine’s short pamphlet never quite achieved the success of either Common Sense or The Rights of Man, but the radical argument presented in the Address—for a republic, a new constitution, and a National Convention elected by universal male suffrage—formed the core of reformers’ demands in Britain for the next 50 years. The London Corresponding Society, from the 1790s onward, called for a National Convention; the Chartists of the 1840s actually held a National Convention, which thoroughly alarmed the authorities; and the hated property qualification for voting was eventually removed in the 1867 Second Reform Act.

It was in Paine’s adopted countries of America and France that his ideas had the most impact —perhaps especially in the United States, where he is credited as one of the Founding Fathers of independence and the Constitution, and where his writings swayed thousands toward the cause of democracy and republicanism.

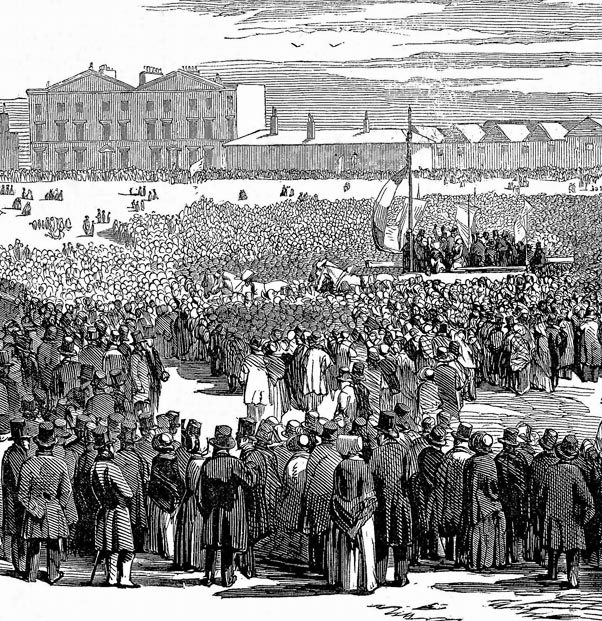

A Chartist Convention held a mass meeting at Kennington Common in London on April 10, 1848, demanding electoral reforms of the kind advocated by Thomas Paine.

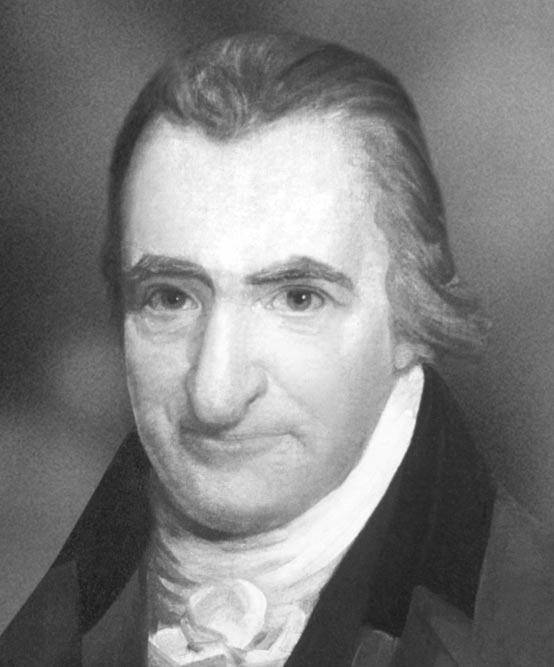

THOMAS PAINE

Thomas Paine was born in Thetford, England. He emigrated to America in 1774, having lost his job as a tax collector after agitating for better pay and conditions. With a recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, he became editor of a local magazine in Pennsylvania.

Common Sense was published in 1776, selling 100,000 copies in three months, among a colonial population of two million. In 1781, Paine helped to negotiate large sums from the French king for the American Revolution. Returning to London in 1790, and inspired by the French Revolution, he wrote The Rights of Man, which led to a charge of seditious libel. After fleeing to France, he was elected to the National Convention there, and avoided execution during the Terror. He returned to America in 1802 at President Jefferson’s invitation, and died seven years later in New York.

Key works

1776 Common Sense

1791 The Rights of Man

1792 Letter Addressed to the Addressers on the Late Proclamation

See also: Thomas Hobbes • John Locke • Jean-Jacques Rousseau • Edmund Burke • Thomas Jefferson • Oliver Cromwell • John Lilburne • George Washington