IN CONTEXT

Realism

Statecraft

4th century BCE Chanakya advises rulers to do whatever is necessary to achieve the well-being of the state.

3rd century BCE Han Fei Tzu assumes it is human nature to seek personal gain and avoid punishment, and his Legalist government makes strict laws.

51 BCE Roman politician Cicero advocates republican rule in De Republica.

1651 Thomas Hobbes’s Leviathan describes life in a state of nature as “nasty, brutish, and short.”

1816–30 Carl von Clausewitz discusses the political aspects of warfare in On War.

Written by probably the best known (and most often misunderstood) of all political theorists, Niccolò Machiavelli’s work gave rise to the term “Machiavellian,” which epitomizes the manipulative, deceitful, and generally self-serving politician who believes that “the end justifies the means.” However, this term fails to encapsulate the much broader, and innovative, political philosophy Machiavelli proposed in his treatise The Prince.

Machiavelli lived in turbulent political times at the beginning of the period that would come to be known as the Renaissance. This was a turning point in European history, when the medieval concept of a Christian world ruled with divine guidance was replaced by the idea that humans could control their own destiny. As the power of the Church was being eroded by Renaissance humanism, prosperous Italian city-states, such as Machiavelli’s native Florence, had been established as republics, but were repeatedly threatened and taken over by rich and powerful families—such as the Medicis—seeking to extend their influence. Through his firsthand experience in public office for the Florentine Republic as a diplomat, and influenced by his study of classical Roman society and politics, Machiavelli developed an unconventional approach to the study of political theory.

A realistic approach

Rather than seeing society in terms of how it ought to be, Machiavelli tried to “go directly to the effectual truth of the thing rather than to the imagination of it,” meaning that he sought to get to the heart of the matter and treat politics not as a branch of moral philosophy or ethics, but rather in purely practical and realistic terms.

Unlike previous political thinkers, he does not see the purpose of the state as nurturing the morality of its citizens, but rather as ensuring their well-being and security. Consequently, he replaces the concepts of right and wrong with notions such as usefulness, necessity, success, danger, and harm. By placing utility above morality, his ideas for the desirable qualities of a successful leader are based on effectiveness and prudence rather than any sort of ideology or moral rectitude.

At the center of his political philosophy is the Renaissance idea of viewing human society in human terms, completely separated from the religious ideals imposed by the Christian Church. To achieve this, his starting point is an analysis of human nature based on his observations of human behavior throughout history, which brings him to the conclusion that the majority of people are by nature selfish, short-sighted, fickle, and easily deceived. His view is realistic, if somewhat cynical, and very different from those of previous political thinkers. While they might appear to be an obstacle to creating an efficient, stable society, Machiavelli argues that some of these human failings can in fact be useful in establishing a successful society, though this requires the correct leadership.

An effective leader can harness the weaker traits of humanity in his people to great effect, in the same way that a sheepdog can manipulate a herd of sheep.

Using human nature

Man’s innate self-centeredness, for example, is shown in his instinct for self-preservation. However, when threatened by aggression or a hostile environment, he reacts with acts of courage, hard work, and cooperation. Machiavelli draws a distinction between an original, fundamental human nature that has no virtues, and a socially acquired nature that acts in a virtuous manner and is beneficial to society. Other negative human traits can also be turned to the common good, such as the tendency to imitate rather than think as individuals. This, Machiavelli notes, leads people to follow a leader’s example and act cooperatively. Further, traits such as fickleness and credulity allow humans to be easily manipulated by a skillful leader to behave in a benevolent way. Qualities such as selfishness, manifested in the human desire for personal gain and ambition, can be a powerful driving force if channeled correctly, and are especially useful personal qualities in a ruler.

The two key elements to transforming the undesirable, original human nature into a benevolent social nature are social organization and what Machiavelli describes as “prudent” leadership, by which he means leadership that is useful to the success of the state.

Advice for new rulers

Machiavelli’s famous (and now infamous) treatise The Prince was written in the style of the practical guides for leaders known as “Mirrors of Princes,” which were common in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. It is addressed to a new ruler—and is dedicated to a member of the powerful Medici family—with advice on how basic human nature can be engineered and manipulated for the good of the state. Later interpretations, however, hint that Machiavelli was using the genre somewhat cleverly, by exposing to a wider audience the secrets already known to the ruling classes. Having explained man’s essentially self-centered but malleable nature, he then turns his attention to the qualities that are necessary for a ruler to govern prudently.

"A prince never lacks legitimate reasons to break his promise."

Niccolò Machiavelli

Sandro Botticelli’s Adoration of the Magi, painted in 1475, includes representations of the powerful Medici family, who ruled Florence at the time Machiavelli wrote The Prince.

Leadership qualities

Confusingly, Machiavelli uses the word virtù to describe these leadership qualities, but this is very different from our modern idea of moral virtue, as well as the concept of virtue as understood by the Church. Machiavelli was a Christian, and as such he advocates Christian virtues in day-to-day life, but when dealing with the actions of a ruler, he believes that morality must take second place to utility and the security of the state. In this respect, his ideas hark back to the Roman quality of “virtue” embodied by the military leader who is motivated by ambition and the pursuit of glory, properties that are almost the exact opposite of the Christian virtue of modesty. Machiavelli notes, however, that these motivations are also a manifestation of human nature’s inherent self-interest, and similarly can be harnessed for the common good.

"In judging policies we should consider the results that have been achieved through them rather than the means by which they have been executed."

Niccolò Machiavelli

Machiavelli takes the analogy between military and political leaders further, pointing out other aspects of virtù, such as boldness, discipline, and organization. He also stresses the importance of analyzing a situation rationally before taking action, and basing that action not on how people should ideally behave but how they will behave (meaning in their own self-interest). In Machiavelli’s opinion, social conflict is an inevitable result of the selfishness of human nature (this is in contrast to the medieval Christian view that selfishness was not a natural condition). In order to deal with this selfishness, a leader needs to employ the tactics of war.

Although Machiavelli believes that to a large extent man is master of his own fate, he recognizes that there is also an element of chance at play, which he refers to as fortuna. The ruler must battle against this possibility, as well as against the fickleness of human nature, which also corresponds to fortuna. He sees that political life, in particular, can be seen as a continuous contest between the elements of virtù and fortuna, and in this regard is analogous to a state of war.

Conspiracy is useful

By analyzing politics using military theory, Machiavelli concludes that the essence of most political life is conspiracy. Just as success in war is dependent on espionage, intelligence, counterintelligence, and deception, political success requires secrecy, intrigue, and deceit. The idea of conspiracy had long been known to military theorists, and was practiced by many political leaders, but Machiavelli was the first in the West to explicitly propose a theory of political conspiracy. Deceit was considered contrary to the idea that a state should safeguard the morality of its citizens, and Machiavelli’s suggestions were a shocking departure from conventional thinking.

According to Machiavelli, while intrigue and deceit are not morally justifiable in private life, they are prudent for successful leadership, and excusable when used for the common good. More than that, Machiavelli asserts that in order to mould the undesirable aspects of human nature, it is essential that a ruler is deceitful and—out of prudence—does not honor his word, as to do so would jeopardize his rule, threatening the stability of the state. For the leader, then, compelled to deal with the inevitable conflicts that face him, the ends do justify the means.

The end is what counts

A prince’s success as a ruler is judged by the consequences of his actions and their benefit to the state, not by his morality or ideology. As Machiavelli puts it in The Prince: “In the actions of all men, especially princes, where there is no recourse to justice, the end is all that counts. A prince should only be concerned with conquering or maintaining a state, for the means will always be judged to be honorable and praiseworthy by each and every person, because the masses always follow appearances and the outcomes of affairs, and the world is nothing other than the masses.” He does, however, stress that this is a matter of expediency, and not a model for social behavior. It is only excusable when done for the public good. It is also important that the methods of intrigue and deception should be a means to an end and not become an end in themselves, so these methods need to be restricted to political and military leaders, and strictly controlled.

Another tactic Machiavelli borrows from the military is the use of force and violence, which again is morally indefensible in private life, but excusable when employed for the common good. Such a policy creates fear, which is a means of ensuring the security of the ruler. Machiavelli tackles the question of whether it is better for a leader to be feared or loved with characteristic pragmatism. In an ideal world, he should be both loved and feared, but in reality the two seldom go together. Fear will keep the leader in a much stronger position, and is therefore better for the well-being of the state. Rulers who have gained power through exercising their virtù are in the most secure position, having defeated any opposition and earned respect from the people, but to maintain this support and hold on to power, they must continually assert their authority.

Though Machiavelli did not sanction the use of questionable methods to get things done in private life, he argued that the ruler should use all means necessary to secure the future of the state.

An ideal republic

While The Prince is addressed to the would-be successful ruler, Machiavelli was a statesman in the Republic of Florence, and in his less well-known work Discourses on Livy, he strongly advocated republicanism rather than any form of monarchy or oligarchy. Despite remaining a lifelong Catholic, he was also opposed to any interference in political life by the Church. The form of government he favored was modeled on the Roman Republic, with a mixed constitution and participation by its citizens, protected by a properly constituted citizens’ army as opposed to a militia of hired mercenaries. This, he argued, would protect the liberty of the citizens, and minimize any social conflict between the common people and a ruling elite. However, to found such a republic, or reform an existing state, requires the leadership of an individual who possesses the appropriate virtù and prudence. Though it may require a strong leader and some scurrilous means to begin with, once a political society is established, the ruler can then introduce the necessary laws and social organization to enable it to continue as an ideal republic—this would be a pragmatic means to achieve a desirable end.

"Since love and fear can hardly exist together, if we must choose between them, it is far safer to be feared than loved."

Niccolò Machiavelli

Machiavelli’s philosophy, based on personal experience and an objective study of history, challenged the dominance of the Church and conventional ideas of political morality, and led to his works being banned by the Catholic authorities. By treating politics as a practical and not a philosophical or ethical subject of study, he replaced morality with utility as the purpose of the state, and shifted the emphasis from the moral intention of a political action to focus primarily on its consequences.

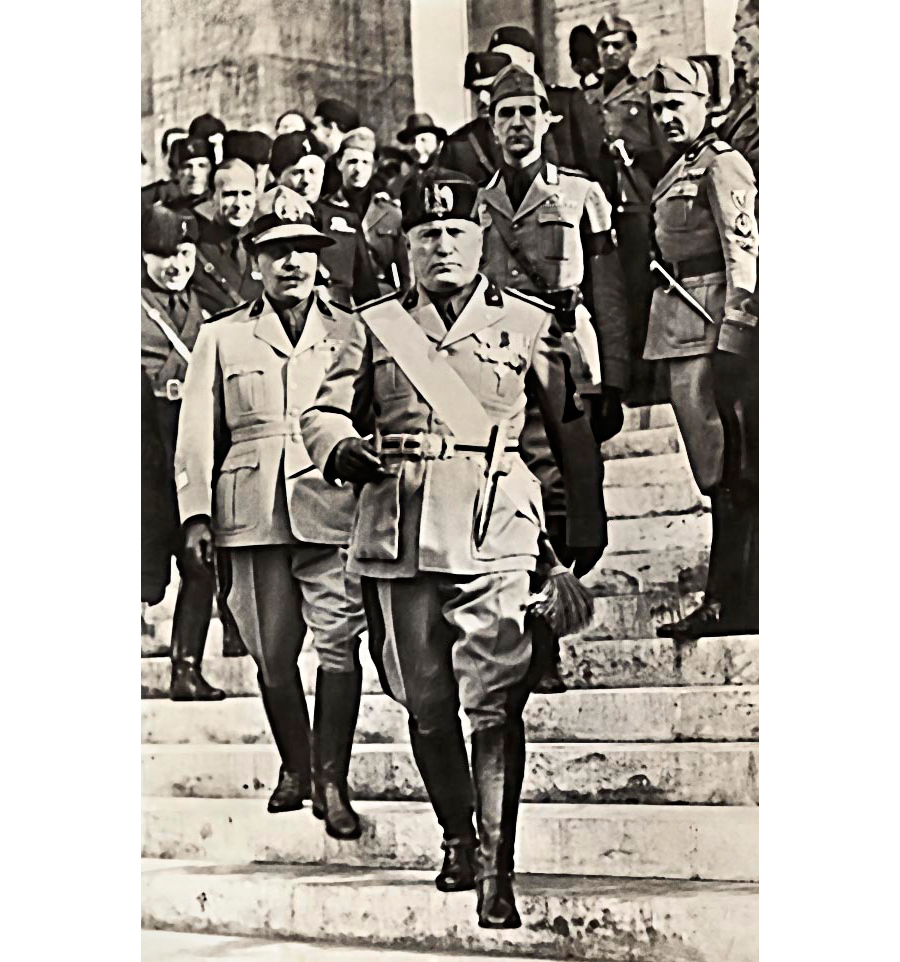

Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was a forceful and ruthless leader, more feared than loved. He claimed inspiration from The Prince.

Enduring legacy

The Prince was very influential in the centuries following Machiavelli’s death, particularly among leaders such as Henry VIII of England, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Oliver Cromwell, and Napoleon, and the book was acknowledged as an inspiration by such diverse figures as Marxist theorist Antonio Gramsci and Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini.

Machiavelli’s critics, too, came from all sides of the political spectrum, with Catholics accusing him of supporting the Protestant cause, and vice versa. His importance to mainstream political thinking was immense—he was clearly very much a product of the Renaissance, with its emphasis on humanism rather than religion, and empiricism rather than faith and dogma, and he was the first to take an objective, scientific approach to political history.

"Everyone sees what you appear to be, but few really know what you are."

Niccolò Machiavelli

This objectivity also underlies his perhaps cynical analysis of human nature, which was a precursor to Thomas Hobbes’s brutal description of life in a state of nature. His concept of utility became a mainstay of 19th-century liberalism. In a more general sense, by divorcing morality and ideology from politics, his work was the basis for a movement that later became known as political realism, with particular relevance in international relations.

“Machiavellian” behavior

The term “Machiavellian” is in common usage today, and is usually applied pejoratively to politicians who are perceived (or discovered) to be acting manipulatively and deceitfully. President Richard Nixon, who attempted to cover up a break-in and wiretapping of his opponent’s headquarters and was forced to resign over the scandal, is a modern-day example of such underhanded behavior. It is also possible that Machiavelli may have been making a less obvious point in The Prince: perhaps he was saying that those who have been successful rulers may have behaved in just as “Machiavellian” a way, but their actions have not been as closely examined. How they achieved their success has been overlooked because the focus has shifted to what they achieved. It seems that we tend to judge leaders on their results rather than the means used to have achieved them.

Expanding this argument further, we might consider how often the losers of a war are found to be morally questionable, while the victors are seen as above reproach—the notion that history is written by the victors. Criticizing Machiavelli leads us to examine ourselves and the extent to which we are prepared to overlook the dubious machinations of our governments if the outcome works in our favor.

Richard Nixon resigned as president in 1974. He authorized a break-in and wiretap at the Democratic National Committee headquarters: actions described as “Machiavellian.”

NICCOLÒ MACHIAVELLI

Born in Florence, Niccolò Machiavelli was the son of a lawyer, and is believed to have studied at the University of Florence, but little is known of his life until he became a government official in 1498 in the government of the Republic of Florence. He spent the next 14 years traveling around Italy, France, and Spain on diplomatic business.

In 1512, Florence was attacked and returned to the rule of the Medici family. Machiavelli was imprisoned and tortured unjustly for conspiring against the Medici, and when released retired to a farm outside Florence. There, he devoted himself to writing, including The Prince and other political and philosophical books. He tried to regain favor with the Medici, with little success. After they were overthrown in 1527, he was denied a post with the new republican government because of his links with the Medici. He died later that year.

Key works

c.1513 (pub. 1532) The Prince

c.1517 (pub. 1531) Discourses on Livy

1519–21 The Art of War

See also: Chanakya • Han Fei Tzu • Ibn Khaldun • Thomas Hobbes • Carl von Clausewitz • Antonio Gramsci