31

The Divine Proportion: Balancing the Golden Rule

James Williams

Nature created it; visual artists follow it. From sea-shells and leaves to flower petals, and yes, a Gecko’s tail, using aesthetically-pleasing framing creatively draws your viewer into your shot composition.

A cold breeze blows across the relic hunter’s face as she approaches the stone tomb. She inches closer as her torchlight dances across the darkened church walls. She reaches out to the stone door—and the torch flame suddenly goes out. Total blackness. The director yells “Cut!” The lights come back on as everyone prepares for the next scene.

As the editor, you review the video replay of the take, and it immediately strikes you that something doesn’t feel right about the shot. The lighting is fine, the acting is solid and the audio is spot on. Then it hits you. The framing of the shot is off, and that’s what feels unbalanced.

It's All in What You See

Whether dealing with ancient subject matter or the dozens of soccer goals your kid scores this season, how you frame your shots is crucially important to how your video will look.

Poorly-framed shots not only leave much of the important visual information out of the picture, but they can also subtly—or not so subtly—create unwelcome tension for the viewer. That’s fine if it’s a horror flick, but it’s not so great if it’s your kid’s fifth birthday.

Composing your shot is also an act of artistic expression. There’s power in pictures. Giving some forethought to how to frame your shot allows you to convey any number of emotions, from fear to peaceful tranquility.

An Age-Old Question

For hundreds—if not thousands—of years, visual artists have been studying how best to frame their subjects and exactly where to plant the focus of their compositions. While there are no definitive rules about how to frame your shots, there are certainly tried and true guidelines that are well worth looking at.

The Divine Proportion

In 1202, an Italian mathematician known as Fibonacci published a book introducing to Western mathematics the numeric symbols we use today. In the same text, he also introduced a series of numbers, known today as the Fibonacci Sequence (see Figure 31-1 ). The first number of the sequence is 0, the second number is 1, and each subsequent number is equal to the sum of the previous two numbers of the sequence itself.

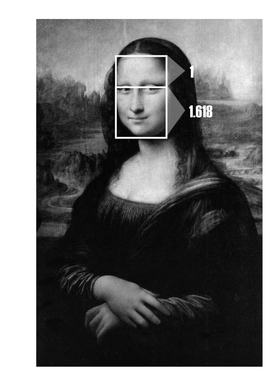

What makes this sequence so special is that eventually, no matter what two numbers you start with, the sequence will settle into a ratio of 1:1.618, also known as the Divine Proportion (see Figure 31-2 ). Curiously, these numbers and ratio show up throughout nature, from the measurements of the chambered nautilus shell to the number of spirals on a pinecone.

The idea behind using the Divine Proportion to frame your shots is that, since it’s found throughout nature, it therefore lends itself to creating intrinsically beautiful compositions.

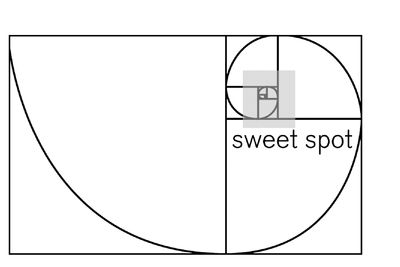

The formula to create a template using the Divine Proportion is fairly technical, so for our purpose, we will illustrate it graphically (see Figure 31-3 ). Each rectangle is half the size of the previous one, tightening up to where the supposed sweet spot lies.

This ratio shows up in architecture, paintings, photography and musical compositions. Leonardo da Vinci supposedly used it in many of his classic paintings and sketches, including the Mona Lisa and the Vitruvian Man. Salvador Dali used it in his portrayal of The Last Supper. And perhaps, now, you can get creative and use it in your masterpiece as well.

One interesting aspect of the Divine Proportion is that many visual artists naturally place the focus of their compositions in the sweet spot, seemingly without knowing it. In many cases, we’ll never know whether some of the great artists

Figure 31-3 and 31-4 The rule of thirds is based on vertical and horizontal lines that intersect within the Fibonacci Spiral. In art and science, these lines are found in many places.

Figure 31-5 An object of interest residing at the intersection of a vertical and horizontal third should be in focus (left). If it is not, in can create an unbalanced look (right).

used these measurements intentionally or if the placement just felt right to them.

The Rule of Thirds

You won’t need an advanced degree in mathematics to sketch out the Rule of Thirds. You simply divide your frame into nine compartments, using two equally-spaced vertical lines and two equally-spaced horizontal lines. Those lines will intersect in four places. Those are the sweet spots, and that’s where you’ll want to place the focus of your composition.

Figure 31-6 Look room is additional space given to the composition, depending upon which way the talent is looking or the direction the talent’s body is facing.

Using the Rule of Thirds allows your subject room to breathe. Human subjects will sit comfortably in the frame, without feeling crowded by the edges of the image.

The horizontal and vertical lines are also good guides to use when breaking up the composition with skylines, waterlines, walls, highways and other straight-line images.

The Subjects of Your Focus

When you first glance at a composition, your eyes will automatically try to extract meaning from the image. There’s usually a focal point that draws your gaze and stands out—a sunset, a drag race, a surfer at the water’s edge. The subject is what the composition is ultimately about. It’s the main object you’d use to describe the composition to someone else. With people, the focus is usually the eyes. In action shots, it can be the center of the activity.

Exceptions to the Rule

Once you have a good handle on the rules, you can think about breaking them. Ignoring these compositional guidelines is a trick you can employ to convey tension in the shot when the situation calls for it.

In general, a subject talking on screen is speaking across the frame with a fair amount of breathing room in front. If you want to immediately create tension, you can take away the breathing room and have your subject speak directly into the edge of the frame.

This technique instantly creates tension, because the subject appears suffocated. It also denies the viewer valuable information about what or whom the subject is addressing off-frame.

The Eyes Have It

You’ll notice that the Rule of Thirds doesn’t line up exactly with the Divine Proportion. But when you compare them against each other, it’s clear there isn’t a huge difference between the two. Seeing where the sweet spots lie in both formulas does offer some good insight into how to compose your shots. Given that all art is ultimately subjective, you’ll need to come to your own conclusions as to what placement works best for you.

Knowing how to create a well-balanced composition is an important tool for every videographer. Like anything worth doing, it takes practice. Eventually, you’ll find yourself gravitating towards well-composed shots that accentuate, rather than distract from, the interesting or emotional aspects of your subject matter. That said, your shots may look terrific, despite ignoring the guidelines. It’s all in the eyes of the beholder. If you think your shot compositions could use some help, these guidelines are an excellent place to start.