28

Production Planning

Jim Stinson

Figure 28-1

The worst cause of video disasters is bad planning—not just during the pre-production phase, but right through to the end of post-production. Professionals don’t just make plans; they implement them and then they follow through on them.

When you plan like a pro, you:

- Plan the shoot in pre-production.

- Shoot the plan in production.

- Edit the planned shoot in postproduction.

This sustained planning and followthrough is essential to delivering a quality video on time and on budget.

Plan the Shoot!

The planning aspect of video creation is so often overlooked that we’ve broken it down into three sections for each phase of production. We’ll start with planning the shoot in pre-production. Of course, pre-production is nothing but planning, from first concept to final schedule.

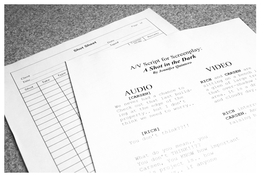

Figure 28-2 A good script and a well-planned shot list are two of the most important planning documents needed for any serious production.

Here, though, we are focusing specifically on developing plans that you can, indeed, shoot and then edit. We’ll look at scripting, casting, staffing, scouting, and budgeting.

We’ll also look at a new planning area: special effects. In other words, pre-production planning relates to editing as well as shooting.

First, The Script

Though writing itself isn’t planning, the resulting script is the basis for every single decision you’ll make in prepping production. Without a complete script, you can’t cast the program, design its look, determine the crew and equipment needed, list the locations or sets, budget the production, or set a schedule.

No, an outline isn’t good enough, even if it’s 50 pages long. Only a true script is specific enough for planning. How about a storyboard? Storyboard sequences with complex action and/or special effects work to visualize the layout of the video, but use a written script for production planning.

For nonfiction programs, a two-column “A/V” (Audio and Video) formatted script will include complete narration and essential audio in the left column and visuals in the right one. Fiction films use the classic screenplay format. The bottom line is this:

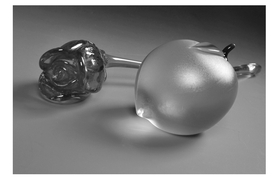

Figure 28-3 A storyboard is a useful tool for visualizing complex action and/or special effects sequences.

when you get to production, you can’t shoot the plan unless you’ve planned the shoot in detail.

Special Effects

People think that special effects are compositing and computer graphics that belong in post-production. However, the most convincing effects are fully planned in pre-production so that location, composite, and CG work can be seamlessly integrated by implementing the detailed plan. That’s why you have to develop your special effects fully even before you scout locations and budget props.

For example, take a spectacular head-on car crash. To achieve the actual impact, you’ll have the cars drive toward and past each other, maybe two feet apart for safety, shooting the master with a long telephoto to conceal the gap between them. In post, you plan to speed up the collision shot and then conceal the fact that they miss each other by filling the screen with a well-timed CG fireball over the live action.

So far so good, but the secret of any effect lies in selling it with supporting shots. To make sure you get them, you need to plan high-speed shots of the individual cars, closeups of the drivers, and maybe a shot across the hood of one car after the crash, as one victim struggles out the door. You plan to put one side of the

129 car up on blocks to tilt it and to increase the tilt by canting the camera off-level the opposite direction. (Note to DP: choose a vague background that won’t reveal the Dutch angle shot, and throw a flickering “fire light” on the windshield, door, and struggling victim.) In post, composite a raging fire effect in the foreground to complete the gag. Every part of this must be planned, right down to the cinder blocks and the fire effect.

The moral is, you can’t just say, “Oh we’ll do the car crash in post.” Only through detailed planning both before and during the shoot can you deliver the raw materials needed to create a classy effect.

People, Places, and Feedback

Even the biggest Hollywood productions are planned and developed by successive approximation: the script describes the requirements; the planners come as close as possible to meeting them; then the script is adjusted to eliminate the resources that were unobtainable and maximize those that were.

This is always true with casting actors. Suppose, for instance, the script demands a beautiful, enticing, evil stepmother; but the closest actress you can find is a frumpy, heavyset person who would look silly vamping around on screen. Happens all the time. So you do some fast script revisions to create a frumpy, heavyset evil stepmother. By planning to fit the circumstances, you save both the actress and the show from embarrassment.

Or take locations. If you can’t find anyplace resembling the dungeon where the evil stepmother imprisons the heroine, you have three choices: remove the dungeon part, create it as a CG virtual set (if you have the resources), or just chain the lady up in a storeroom or something.

Again, if you plan these adjustments before production begins, you can still shoot the plan; but if you haven’t invested in the planning, you’re going to arrive at an unconvincing “dungeon” location and

Figure 28-4 Scouting locations ahead of time can help you avoid a wide range of production problems.

have to improvise a fix on the spot. That seldom works very well.

The All-Powerful Schedule

In reality, budgeting and scheduling are two halves of a circle. Scheduling brings the right cast members, crew, and equipment to the right location at the right time, crucial if you’re paying people by the hour or day and just as important if folks are donating their time.

With good planning, you can also save big bucks (that’s where scheduling and budgeting play tag with each other). For instance, if that antique fire engine rents for $200 a day, you’ll want to schedule all its scenes back-to-back so you can return it as soon as possible.

Oh, and how is it going to get to your location? I once rented an antique vehicle without knowing it didn’t really run. At the last minute, I had to put out expensive, unbudgeted bucks for a day’s use of a platform-bed tow truck.

This is also true for anything else that’s time-sensitive. With meticulous planning, you’ll always have the correct cast list at the proper place with the required equipment and props, all ready to shoot. Without planning, everyone ends up standing around, and that’s not good.

And if it rains or something else goes. A planning pro will have a contingency plan: a way to shoot something

Figure 28-5 Scheduling programs like Microsoft’s Outlook can greatly help you set up a schedule for your production, and easily share with others.

else until you can resume the original schedule.

Money, Money, Money

Professional production accountants must keep tiny altars to the spirit of Murphy, on which they burn symbolic dollar bills, because on a shoot, anything that can possibly go wrong will go wrong. Corollary #1: everything that goes wrong costs money.

Everything. It goes without saying that good production planners budget the show line-item by line-item, right down to cold cream for the makeup department. Then they run an eagle eye over every aspect of production. Does one character throw a vase at another? How many takes might that require, and how many replacement vases? Does one sequence call for actual snow? What will the weather be like and how many days might be lost while waiting for the fluffy stuff to start falling?

Obviously, every production is different. If you’re taping the CEO’s speech in her office, you’re probably very safe. If you’re covering whale migrations from the subjects’ POV, good luck.

Since you don’t have unlimited funds, you can’t just say, “well, whatever it takes.” You have to cast a cold planner’s eye over every script page to spot every place that could run over budget. Then you add a contingency fee for protection.

Then you double it, and pray.

That’s it for creating a production plan. Next, we’ll see how that plan structures the actual shoot so that you can end up editing the show you started out to make.

Shoot the Plan!

Plan the shoot, shoot the plan, edit the planned shoot.

That’s the mantra we introduced earlier. Talk about obvious! Not so fast. If that deceptively simple rule were routinely followed Hollywood epics would never overrun their schedules and amateur productions would never look embarrassing (assuming they didn’t crash and burn before completion). So let’s review reasons for staying on-plan, gremlins that attack production plans, and ways to protect yourself against disasters, both serial and parallel.

The underlying concept is that crucial decisions are made in pre-production planning that will affect everything that follows, all the way through to the end of post-production. A good planner keeps that long timeline in mind, the way a good chess player thinks many moves ahead.

Stick to the Plan

Sticking to a plan no matter what seems sort of, well, retentive; but there are several reasons for resisting changes or at least studying them very carefully before making them.

First, remember the law of unintended consequences. Even small productions are complicated organisms with many interdependent parts. If you decide to shoot, say, scene 22 instead of scheduled scene 14, the cast, location, and time of day might be fine—but what about the actor’s distinctive Grateful Dead shirt, which got all muddy in scene 13 but has to be clean again for scene 22? Thinking fast, you run it through a Laundromat during lunch break. Uh-huh, but when you go to scene 14 later that shirt has to be dirty again—with exactly the same stain pattern as before it was washed.

So things start to domino. Cleverly, you have the actor play scene 14 without the shirt, adding a line like, “Boy, I hope I can get that shirt clean; it’s an heirloom.” Right away, you’ve handed the editor two problems. Since the action is continuous across scenes 13 and 14, the character has

Figure 28-7 What might seem like a minor change in wardrobe can quickly turn into a large out-of-control, chain reaction avalanche that could bury your production. You did such a great job planning, now do a great job of following it.

no off-screen time in which to take off the shirt. Major jump cut. Also, the added line tells viewers that the shirt’s valuable, which is totally irrelevant to the story and distracting from the point of the scene.

You’re already thinking of 50 things at once, under time and money pressure to move, move, move! If you must make alterations, take the time you need to think them through. The second moral is that post-production is very demanding. Once you wrap production, it’s expensive and often impossible to re-open the shoot for vital pieces that are missing or mismatched to other pieces.

The Enemies of Planning

The first big foe of systematic shooting is good ol’ Murphy’s Law in all its many forms. Things go wrong; stuff happens; you have to roll with the punches.

Outdoors, time and weather are huge factors. Obviously, you can’t shoot if it’s pouring rain, and even if it hasn’t started yet, the light in that sullen overcast before the storm doesn’t match yesterday’s sunshine. As for time, an equipment malfunction held up the shoot until yesterday’s pearly dawn turned into high noon.

Whether outdoors or in, personnel are always a problem, especially when they’re

Figure 28-8 and 28-9 The script says the scene takes place on a sunny day and it’s pouring out. Instead of re-working the script, you should have a “plan B’, (and maybe a “plan C”), for when the inevitable Murphy’s Law occurs.

not getting paid to show up on time and keep working all day. You might limp along without a certain crew member but if the performer isn’t there, the show doesn’t go on.

Inanimate objects are just as bad. People bring the wrong wardrobe; props are missing, equipment malfunctions. When you arrive at the gym where you got permission to shoot the “hurricane disaster relief center” you find it’s been decorated for the Senior Prom.

Above and beyond Murphy, there’s another threat to shooting as planned: your own creativity. You show up at the vacant lot to find that there’s a carnival set up there. Wow, what visuals! What production values! Thinking fast, you replace half your planned setups to exploit the unexpected dividend. Or maybe it’s just a brainstorm on the set: hey! why not do it this way instead? Either way, you risk omitting stuff the editor will need and adding stuff that doesn’t belong in your program.

Cover Your Caboose

No shoot is ever completed exactly as planned, but you can minimize the risks by following a few vital procedures.

First, always have Plan B ready. If weather might be a problem, identify indoor scenes with the same cast and have the locations, costumes, and props

Figure 28-10 The people who make six-digits plus making movies view their “dailies” at the end of each day and so should you. Just make sure you don’t accidentally leave the record head in the middle of a scene and record over your work.

standing by. If performers are flaky about showing up, know where to find them and how to shoot around them in the meantime. The trick is to identify the vulnerable parts of your plan in advance and have alternatives ready to go.

Second, learn how to adjust plan A. Understand that a simple thing like a dirty shirt can ripple all the way to post-production. Take the time and care to work out all the implications of proposed changes.

Next, know when to quit. Nothing is more frustrating than doing all the work of getting a day’s shoot together and launched, then sending everyone home again. Your instinct is to say, OK, let’s call Fred and Wilma and see if they can go over to the church and shoot their stuff today,

Figure 28-11 It’s important to not only shoot with a plan, but also edit with a plan. Always keep a script within arm’s reach.

and try to rent that ’57 Chevy, oh, and phone the church sexton, and . . . Uh-uh. This kind of desperate improvisation may keep your crew busy, but the results will be hasty and undercooked. You have to develop the good judgment to know when you’re licked for now so that you can live to fight another day.

Finally, review your footage, preferably before you wrap at any one location, but at least at the end of every shooting day. In even the most professional production, you’re going to find stuff that’s inadequate, wrong, or just plain missing. Before matters go any further, make the notes you need to get pickup shots, to retake bad stuff, to re-think and re-stage sequences that plain don’t work. Then plan the reshoot as meticulously as you planned the original. When post-production starts, you’ll bless yourself.

Next, edit the shoot you planned.

Edit The Plan!

Post-production is supposed to fulfill the promise of pre-production (the script) and production (the shoot). Editing, they tell you, pulls everything together and delivers the program envisioned by the producer, director, and sponsor.

As usual, reality falls short of theory, because editors almost never get exactly the raw material they expected, and they don’t always shape it as well as they might. Earlier we talked about planning the shoot and then shooting the plan. Let’s wrap it up here by seeing how to carry planning forward into post-production.

In a nutshell, you work as hard as you can to complete the original vision, and, where that’s impossible, to make the best program you can with what you’ve got. To do this, you need to systematically evaluate and deal with your raw material and then systematically mold it throughout post-production. In both cases, “systematically" implies that you’re doing some planning of your own.

In the best production setups, the editor is in on the shoot, evaluating each day’s footage and providing feedback to the director to ensure that he can edit the show to the original plan. Too often, however, the editor joins the process after shooting wraps and is presented with a done deal: here’s the stuff, now.

Planning for Post

First off, a good editor is not an auteur (a director who is believed to be the major creative force): Your job is not to express your own vision, but to carry out the vision of the writer, director, producer, or whoever it is that presides over the production. With that in mind, you should take your very first step even before you start screening footage: you should discover (or recollect) what the original plan was—what the program was supposed to be. Typically, that means reviewing the concept with the producers or, at the very least, closely re-reading the script. Only when you have the original concept freshly in mind can you start dealing with the footage.

Build a program. This is the real-world situation we’ll talk about here.

The obvious next step is to review all the raw material, constantly comparing it to the program concept. First and foremost, did they shoot all the material needed? (You’d be surprised how often

Figure 28-12 Make sure producers acquired all the planned video and audio by checking the footage against the shot list and marking where you need pickup shots or changes .

they didn’t.) Does the footage they did shoot do its job? Are the establishing shots and closeups and inserts taken of the right stuff from the right setups? Is the technical quality uniformly up to par?

And don’t forget the audio. Is the production sound good quality (or even usable)? Did they record background tracks, ambient sound, and wild sound? Have they planned the music to use and how to use it, or are they leaving that to you?

After a thorough review of the raw material (and a yellow pad bristling with notes) you’re ready to plan your post-production strategy. First of all, what absolutely has to be shot (if overlooked) or re-shot (if loused up)? For example, your documentary on glass blowing covers the whole process of making a vase, from molten glass to finished . . . Whoops! The beauty shot of the completed work is badly lit and out of focus. Try as you might, you can’t think of a way to drop the poor shot and edit around it because it’s the whole point of the program. So it has to be re-shot.

And as long as they have to send a crew back out, what other shots can you improve? What missing angles could be picked up? (Which is why they’re called “pickup shots.”)

Sooner or later, you’ll run up against a wall: you can’t get more coverage of the master glass blower because she promptly retired and left for Maui. Now your strategy shifts to developing Plan B. Studying the footage you discover two things: Several shots (some with multiple takes) in which her body blocks the furnace opening, so you can’t quite see what she’s doing. Inserts of her assistant’s bare hands and arms that look similar to hers.

Gotcha! Plan B is to support shots of the blocked furnace door with narration explaining what she’s doing (even though she was doing something else) and shoot the missing inserts with the assistant’s hands and arms subbing for the Master’s. In summary, then, you evaluate your raw materials, reshoot where it’s feasible, and plan workarounds where it’s not.

With plans A and B implemented, you do your best to create the finished program as originally envisioned.

Planning the Edit

With your post-production strategy worked out, you’re ready to turn the raw footage into a work of genius. Here too, you need a systematic plan, though admittedly, the plan is much the same for most editing jobs.

The problem with digital post is that it encourages you to do everything at once: find the shots, assemble the sequence, trim to length, build the tracks, add CGs and graphics, repeat with the next sequence, and so-on. Completing one sequence at a time, you’re more likely to end up with a bunch of individually fine pieces that refuse to fit smoothly together. Instead, it’s generally (though not always) better to work vertically instead of horizontally: go through the entire show, doing one job—building just one layer—at a time. Here’s how it works:

First, break out and catalog all your footage at once. Why? I can’t tell you how many times I’ve plugged a hole in one sequence by remembering a shot I could steal from a different one. You need a mental inventory of all your footage before you start.

Then begin assembling your show, sequence-by-sequence, to be sure, but without worrying about fine-tuning. Once you’ve previewed the result, you’ll have a good feel for the way the program’s coming together.

Figure 28-13 and 28-14 A plentiful supply of cutaways will save an editor’s. . . reputation. If you can get to the production crew before they shoot, request cutaways.

Now do your tuning, trimming shot lengths, adjusting cut points, pulling whole shots that turn out to be superfluous. By working the whole program at once, you keep a feel for its rhythm and pace.

So far, you’ve had just the production track, if any. Now it’s time to pull things together with audio, layering ambient and background tracks, adding sound effects, timing narration, selecting and adding music.

Finally, you’re ready to begin adding CGs and graphics: transitions, titles, and the like. Again, seeing the show as a whole will help you keep them consistent.

And don’t forget the DVD (which will almost certainly be your release format). As you polish the show, start looking for the material to repeat as backgrounds for your disc’s main and sub menus.

So, do your strategic post-production planning by evaluating your materials and deciding exactly what you want to do with them; then do your tactical planning by working through the editing process one careful layer at a time.