42

How to Make a Documentary

Randal K. West

Few other communication forms have the power to reveal a unique perspective, capture imagination and even motivate change. We break down the process of how to make a documentary into three parts so you can discover how to move your story from dreaming your documentary concept, fulfilling the dream and sharing your vision through distribution.

To Dream a Possible Dream

Walk onto the working set of any television production studio and almost every person on the crew has a documentary they are shopping around, getting ready to shoot, or trying to fund. Why? Because everyone from the director of photography to the key grip has a story to tell, they feel compelled to share their stories with a larger audience.

Figure 42-1

True, the percentage of would be documentary filmmakers is potentially greater within the film/television community than among antique car salesmen, but there are many people from all walks of life who want to share their story or a significant piece of history through documentary filmmaking. In today’s world dominated by high tech gizmos and reality TV, documentaries have never been more popular and the equipment to shoot and edit them more accessible and inexpensive.

Is Your Story Compelling?

The founder of our agency and I were approached one day by a reasonably well-known and respected individual in our community. He wanted to pitch a documentary idea to us for possible production by our company. The man went on to explain that although he still seemed to exist as a “regular” guy in our community, since his divorce he had lost everything and was living between his car and an abandoned building. We asked many questions, but despite his having managed to hide his status from the rest of the community, there just wasn’t a strong enough plot line to hang a documentary on. We felt horrible for the guy but there was no universal truth, no significant lesson to be learned that we felt warranted filming a documentary.

Two months later a woman named Patti Miller came to my office and described how 40 years ago as a Drake University junior, she had traveled to Mississippi to participate in the Freedom Summer, in order to help African Americans sign up to vote. Patti, “a lily-white Iowa girl” was fundamentally affected by her experience, an experience shared by others who had participated. She pointed out that the fortieth anniversary of Freedom Summer was approaching and many of the volunteers were now in their fifties and sixties. Patti’s story was a part of history that could easily start to slip away and the 40-year anniversary presented a seminal opportunity to share the story. The story moved me, and my crew and I headed to the South to start filming. Patti’s story had universal appeal and importance. We decided that we would tell this story of national racism, politically controlled hatred, and the individuals who fought oppression, through the very personal eyes of one Iowa undergraduate female, alone and out of her home state for the first time in her life.

Tell Me a Story

What’s your story? Is it universally applicable? Is it simply a slice of life anecdote, but very funny or very profound? Would someone who doesn’t know you care or benefit from becoming aware of your story? Is it a scholarly piece addressing an issue or topic discovered through research and others should be made aware of? Could others benefit by seeing the world through your eyes, watching you follow a particular person or group of people around as they do what they do? If you can find a way to turn your personal experience into a universally shared or recognized experience, you have the foundation for building a documentary. At this point, identify your eventual audience and keep them in mind as your documentary morphs toward its final form.

Putting it Together, Bit by Bit

So, you’ve got your story, now what? Old fashioned as it may seem, try to get all the elements of your story written down in simple outline form using 3 × 5 index cards. Keep it loose and put each element on one 3 × 5 card so you can shuffle and re-shuffle them. Lay your story out and look at it. Examine all your possible elements. (Of course, you can do this with a computer too, but the index cards work well for sorting out thoughts and ideas.)

If you have old 8 mm film from your youth, log it and list it as an element. Do you have old photos or access to old newspaper articles? Who are the people you want to interview and what subject mater will they cover? Record every element and every topic on a card and separate the cards with only one topic or element per card. Lay them out in an order that makes sense to you and use this to create your first outline. Keep these cards! You will use them over and over again.

Dramatic Structure

Every story needs three things, a beginning, middle, and end. You must define where these points exist in your story. Does your story have a great hook that will involve the audience from the outset and

Figure 42-2 You may not have used index cards since grade school, but they are a great tool to help you and your creative team pre-visualize the project.

hold them? Is it most effective when told chronologically or should it jump around in time? Will your story be narrated? Will you write the narration, or will the subjects you interview tell the entire story in their own words? Will it be a combination? You must discover what is most dramatic and engaging about your story and tell it in a way that highlights those points.

Tone and Treatment

How do you want your story heard? Do you want to create a formal documentary with voice-over narration and drops to interviews and B-roll, or do you want to do a Cinéma Vérité piece where the camera seems to just exist as it captures everything around it? Many documentaries

Figure 42-3 How will your finished piece look or how do you hope it will look? Storyboards or large sketches will further help you communicate with your crew to assure everything proceeds as smooth as possible once the camera starts rolling.

these days have the raw reality look of the “Cops” TV show with handheld cameras loosely carried on shoulders. Other documentaries use guerilla tactics; they surprise people by simply shoving a microphone in their face. Michael Moore is famous for this.

An Emotional Center

Regardless of your choice of treatment or subject matter, almost every documentary needs an emotional center. The audience needs someone or a group of “someones” to care about. A message or idea is not enough. The characters in your documentary will carry your plotline as strongly as your storyline. Very few documentaries based solely on intellectualism succeed. Give your documentary some heart and some emotion. Give us someone to root for.

Formulating a Plan

As soon as you have determined the structure and treatment of your documentary, you are ready to take your outline and create a projected timeline and budget. In order to create a budget you must decide the format in which you want to shoot your project. Will you shoot film or video? What type? How often will you need sound? Will you be lighting with instruments or will you be shooting in available light? How many days and in how many locations will you need to shoot? How big a crew and how much equipment will you need? How long and with what means will you edit?

After you answer these questions, you will be in the best position to get close to a bid for creating your project.

Go Find Some Funding

Collect your outline, timeline, bid and distribution plan (distribution will be fully covered in part three of this series but it must be fully fleshed out in your pre-production planning if you wish to raise funds from someone other than your parents or credit cards). Create a printed proposal using these elements to pass for your fund-raising efforts to support your project. Documentary film budgets can run the gamut from low-budget to multi-million dollar ventures, but many make it on a very limited amount of hard capital. Documentary filmmakers as a group are notoriously successful at getting “sweat equity” from people who volunteer their equipment and their expertise for a stock in

Figure 42-4 A detailed budget is an extremely important part of your pre-production planning. You don’t want to be halfway through your project to realize the funding is depleted. Factor in every possible expenditure and then add a 1% contingency.

the project. There will always be some hard costs though, and if you are not in a position to cover them yourself you should see an attorney and get help setting up a simple system that will enable you to accept funds on behalf of your not for profit project. Some filmmakers seek financial support by asking existing nonprofit organizations to sponsor their project, then take in the funds, and allocate them back to the filmmaker.

Fulfillment of the Dream

Considered an art form by many, documentary video production has its own special challenges and rewards. In this part of this story on how to make a documentary, we’ll explore how to plan your approach, find your subject and begin the process of bringing your vision to fruition.

Once you’ve chosen your topic for your documentary, you still have many choices facing you. How do you want to approach your subject? Will your documentary seem to have a passive feel? Will the story be told by the people who are interviewed as the story comes out in their own way, or will an aggressive interviewer (e.g., Michael Moore) drive the interviews, or will you mix interviews with written narration to be delivered in voice-over? Will your documentary be a balanced view of an issue where both sides are equally and fairly explored? What criteria should help you make these decisions?

Point of View

Whose story is it really? You can choose to not have a “voice” in your documentary and make it “news” style and as impartial as possible, or you can choose the individual or group that is most affected by your story and let it be their story. This doesn’t mean you can’t explore both sides of an issue; it just means that you are going to put a real face on one side of the issue and allow them to personalize the story. A compelling documentary should not only be factually correct, but it should be engaging and emotionally compelling. You can also personalize both sides of a story. We have said for years in the advertising business, “don’t just sell the steak, sell the sizzle.” Find the sizzle in your story, because that is what is going to eventually get you distribution, and remember that even a personal story should have some universal appeal.

Sound Issues

Never take sound for granted. Nothing ruins a video that is shot on a budget quicker than bad sound. I always fight to get a sound person who is solely responsible for sound, because it is that important to me. If we truly can’t have the extra body, I will listen for sound as I direct, as I don’t feel a camera operator can split his attention well enough to both shoot and listen effectively at the same time. That said, there have been times when I have both shot and monitored sound; you just increase your percentage chance of having a problem. Use a lapel mic on the person you are interviewing and if possible put a pole mic on the other channel right out of your shot. Blending these

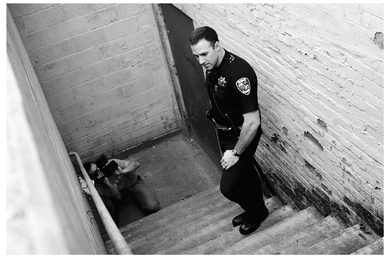

Figure 42-6 Sound matters. Pay attention to your setup, and shoot on location for great emotional reactions.

two microphones together in post will give you a rounder and fuller sound. If you only have access to one mic, make sure the sound is as pristine as possible. Listen to the room before you shoot and turn off air changers if you can. Also take the time to record room tone (everyone sitting in the room making no noise for 30 seconds) or outside ambient sound, as this will help your editor remove background noise in post.

Shooting

If you don’t know the camera well, you can probably survive mostly on factory settings. You do want to be aware of the iris setting and watch for backlight that becomes overwhelming. Always white balance every time you change locations. When in doubt, keep your shots simple and clean. As you gain confidence you can shoot “walk and talks,” but when you’re just starting out, find a safe, pretty environment to shoot.

Conducting Interviews

I rarely have a subject speak directly to the camera. Unless they are doing a direct appeal to the people watching the video, they should not speak directly to the lens. Sit directly next to the lens, either to the left or right with your eyes at the same height as the lens, and have them speak directly to you. Don’t feel like you have to just jump right into the subject of the interview. If you don’t know them, spend some time getting acquainted. Ask about what they like to do. Find out who they are and then lead them into the subject you want. The cheapest component of your project is the videotape, so let it roll. This is a technique to make them feel more at home in front of the camera, but sometimes you also discover gems you didn’t think you’d find. Also, listen! Don’t be so wrapped up in the questions that you have planned to ask that you don’t listen to what is actually being said. Ask unscripted follow-up questions and closely explore their reactions. Let them control some of the content of your interview. Be very open to finding a surprise and letting it blossom into something wonderful.

B-roll

Keep track of everything your interviewer says and keep in mind possible B-roll shots that could highlight this dialogue. A-roll is when the camera is on the subject and the words are coming out of their mouths. B-roll is footage without sound that is shot to break up the talking head portions of an interview and is inserted in place of the talking head during the postproduction process.

Documentaries rely on old pictures or licensed stock footage many times, but those elements can be expensive even for smaller projects and the licensing can limit how and where you can show the finished piece. Reenactments are a way to create footage that can help fill the needs of the project. If you are doing a piece about the 1960s, you can find old civic buildings that

Figure 42-7 Shoot plenty of cutaways and angles. Your B-roll shots will be invaluable for insertion over your interview audio.

still look as if they are in the 1960s. Go to someone’s attic or to a thrift store, locate appropriate wardrobe, and create your own footage. You can pull this footage into sepia tones or make it black and white in post. You can blend this created footage with the old photos you can find and it will give the piece a sense of movement.

Discovery in the Moment

If your documentary is taking a person back to an event or a moment that changed his/her life, if you can afford it, don’t just talk about it but go there. Shoot the first time they see this place after so many years and let them just describe what and how they feel. If there is a significant person who helped them at one time, don’t just talk about it. Shoot them meeting again, and get the energy of that exact moment.

Finding your Vision

Every documentary should begin as a blank sheet of paper or a canvas to paint upon. What colors you use and what format should come from a combination of you as an artist and the content of your story. Content should always dictate form, but you are in this equation as well and it will be your passion that drives this project. Five filmmakers could attempt the same topic for a documentary and each would most likely create a piece that only resembles the others by subject matter and that is as it should be. Find what excites you, then find your own means to express it.

Figure 42-8 Go back to the location where pivotal events happened within your story to give your audience some additional perspective.

Share the Dream

You found the “story” that needed to be told, you scraped together enough funding to shoot and post it and now you have an end product that you and your small circle of best friends think is great. But now what? Our final look at making your documentary shows you several ways of getting your story seen by the masses. Festivals are one of the first places you should look to get your project noticed. Start by building lists of potential places to show your film and group these into at least two categories: festivals that are well known and often lead to distribution, and festivals that are grouped by production type or topic (i.e., an all female film festival if your work was all done by women, or a film festival that celebrates stories from the South for documentary about Freedom Summer in Mississippi). Most festivals will charge admission and you need to count this as a loss even if your film doesn’t make the selection cut.

Your Own Backyard

Look locally. There are at least 15 film festivals each year here in Iowa that feature projects created within the state. Contact your state (or even county) Film Commission to get a list of all the local film festivals. If you can, speak with someone in the film office and tell him or her about your film. Their job is to promote films produced in state, so allow them to offer their suggestions for local distribution and attention. (This Videomaker forums page lists US Film Offices by state, is a good place to start: www.videomaker.com/community/forums/topic/us-film-offices-by-state.)

Public Television

Accessibility to public television will vary greatly from state to state and even regionally. Iowa, for example, has a very developed public television programming department that is very accommodating in terms of providing information and support for our documentaries. They even offered seed monies for one of our projects, but we decided to self-fund and maintain complete rights until the project was completed. They did, however, refer us to ITVS (Independent Television Service), which is a service that assists filmmakers and showcases independent producers.

Unfortunately, much of what you have heard about the state of public television is probably true. They still seek first-quality programming and though open to documentaries, they are no longer the land of “milk and money.” Public television has become quite dependent upon grant and gift monies to support project funding.

Cable Distribution and Television Syndication

What cable outlet or broadcast channel is the best possible match for your project? As more and more channels become available, the appeal of each channel becomes more selective and niche oriented. Many cable channels run a high level of documentary programming and much of it is tied to a very specific topic (E Entertainment, Style, the History Channel, Bravo). Some cable channels are connected to entire cable networks. The Discovery Channel is a flagship cable station connected to 14 other cable channels including Animal Planet, The Learning Channel, the Travel Channel, and FitTV. If you contact the Discovery Channel distribution office they can send you the required forms for submission and will help move your material to the proper cable outlet.

The internet

The internet is exploding with showcase opportunities. Many websites allow for very extensive streaming video. Does your project relate to or help clarify some aspect of someone else’s website? Could a portion of your documentary play on their website via streaming video and then be offered for purchase? Do you have your own website where you can sell your end product? If not, and your documentary is one that people might purchase if they knew it existed, you probably should be selling it through a website. Make sure the site is clean and simple and has a shopping cart that allows others to purchase your documentary in a variety of either downloadable formats or DVD.

Vidcasting

Vidcasting (also known as video pod-casting, vodcasting, and other names) is different from streaming. It is a method of transmitting up to broadcast quality video via an RSS feed (Really Simple Syndication) to a computer. This method of video sharing provides a low-cost, broad and immediate marketplace for video distribution by enabling users to

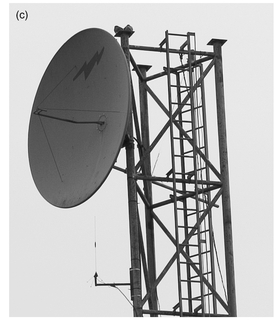

Figure 42-10 A satellite uplink sends video to a satellite; a microwave dish sends video to a TV transmitter and movie theatres send video straight to the viewer.

receive continuous, high quality updates directly to their personal computer. Independent producers and filmmakers can benefit greatly from this technology as it enables them to cut out the middleman and make their videos instantly accessible to a wide audience at TV broadcast quality.

Independent filmmaking especially documentary filmmaking is by nature a challenging area of video production and finding a viable distributor presents a special challenge all of its own. If you are new to the documentary arena, this is an opportunity for others to see examples of your work and for your exposure to networking and marketing opportunities. If you are ready to start selling or marketing your work, you can create a sample or a trailer of your documentary and encourage those

Figure 42-11 A well-designed website may be the best tool available to get your project in front of thousands of eyes across the globe.

who see your sample to go to your website to purchase the entire piece.

Educational Video

An internet search for educational videos will bring up a substantial list of catalogs and services that specialize in videos and documentaries appropriate for classroom and educational purposes. If your documentary qualifies as a possible option in one of these catalogs, it would certainly be worth a study-guide for your documentary if they request one.

Finding Funds for Distribution

Fundraising to help find distribution outlets and marketing opportunities for your project is different from looking for “seed” money. You already have a relatively finished end product and now you simply need help finding ways to get people to see it. In our small town, there are many known businesses that routinely give to special projects. The cost of underwriting the marketing for your documentary will probably not be that much more expensive than underwriting a good-sized event for your town or for an organization.

Take your outline, your budget and a one-page synopsis of your project which includes not only your subject matter but why your “subject matters,” along with possible areas for distribution to the meeting. If you can create a short 3–4 minute DVD that can function as a sample reel of your documentary, it can be a very motivating portion of your pitch. Take a portable DVD player to the meeting just in case. Have a detailed marketing plan for your project that shows all the festivals you plan to enter, all the ways you want to present your documentary, and the costs for this exposure.

You don’t need a formal business plan at this point, unless you are truly attempting to raise a substantial amount of money. If that is the case you will need to create a formal business plan that includes projections for how the money will be returned to those who invest. Many documentary filmmakers have been very successful at raising dollars in support of their endeavor while promising no more than a credit listed at the start and finish of the documentary. PBS won’t allow much more than a simple acknowledgement of support. You do however need to know how you plan to accept the funds if an individual or a company offers them to you. If PBS partners with us on one of our projects, anyone wishing to donate to the project designates the funds as a gift or

Figure 42-12 Organizations such as the Foundation Center can assist video producers with fundraising right from the internet. ( www.foundationcenter.org ).

grant to Iowa PBS. PBS then re-allocates the funds back to the project. Sometimes the organization which functions as the “pass-through” will charge a “processing” percentage to cover their time and effort.

Last Thoughts

We have now traveled the full course of documentary filmmaking. We have discussed finding a subject, defining your style, the technical requirements for bringing that vision to video, and how to market that video to a group of people. Like any artist or craftsman, you are now equipped with the necessary tools of your trade. We look forward to one day hearing some breathless documentary filmmakers at the Academy Awards stating how an article in Videomaker helped get them started. Hey, we can dream too, you know!