69

What's Legal

Mark Levy

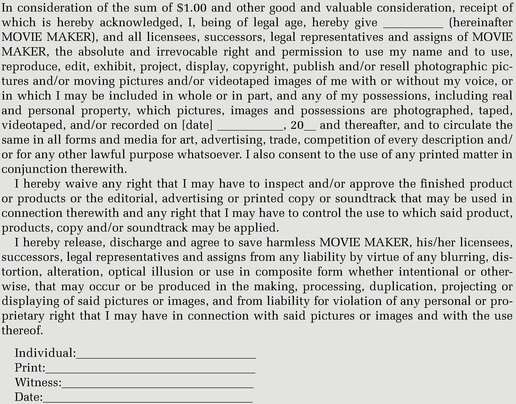

Figure 69-1

As video producers, we’re often gifted with an intimate look at people, places and events in the world around us. . . but we’re surrounded by legal time-bombs waiting to blow our video apart.

Your life as a producer is not always easy. In addition to dealing with myriad creative and technical issues, you have to try not to be sued and not be arrested just trying to perform your job.

Creating videos under the law is all about trade-offs and compromises. As a lawyer, I am often called upon to weigh the rights of creators, such as movie makers and news reporters, against the rights of private individuals. Although you live in a free country and have the right to say almost anything about any subject, you still have limitations on those free speech rights. The public’s right to know must be balanced against private citizens’ right of privacy. You cannot infringe on the copyright and privacy rights of others.

The Copyright Act

When it comes to making videos, perhaps the simplest law to be aware of is the Copyright Act (Title 17 of the United States Code, www.copyright.gov), which is a federal statute, applying to people in all states. In fact, some of the Act

Figure 69-2 If a Cease and Desist letter arrives in your mailbox, take the issue seriously. At best, it’s just a warning. At worst, it’s the first step to a lawsuit. At this point, you may want to consider professional legal help.

applies to people in other countries, as well. Our copyright laws are based on the US Constitution (Art. 1, Section 8, Clause 8), written long before camcorders were invented. As a matter of fact, the Constitution became effective in 1789, before photocopiers, computers, cell phone cameras, videotape and DVDs. But copyright laws are updated from time to time and now cover all of the technology you are likely to use.

Simply stated and without an agreement to the contrary, a person who creates an original work is automatically given the exclusive right to:

- Reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords. (Some of this terminology was last updated in 1905 . . . that’s right; this update was more than 100 years ago.)

- Prepare derivative works (i.e., works that modify and are based upon the copyrighted work).

- Distribute copies of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or rental.

- Perform the copyrighted work publicly.

- Display the copyrighted work publicly, in the case of individual images of a motion picture.

- Perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission, in the case of sound recordings.

As used in the Copyright Act, what does “exclusive” mean? In this context, it means the creator of the work has a negative right: the right to exclude others from performing these activities.

If you decide to use someone else’s music or sound effects or still images or film or video moving images without permission, you can be subject to a lawsuit or, when the infringement is willful, even criminal charges.

What to Do?

The absolute best solution to the copyright quandary is to create everything yourself—shoot original video, add original sound effects, and compose and perform your own music. Unfortunately,

Figure 69-3 You can find a large array of forms from talent releases and rental agreements to shot logs in Videomaker’s Book of Forms: www.videomaker.com/store. You can also download legal forms at www.copyright.gov.

for most of us, this is easier said than done. Alternatively, you may hire someone to do at least some of this work. In that case, if the creator is an employee, the work would be a “work made for hire,” as defined in the copyright statute: a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment, or a work specially ordered or commissioned for use as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work. Be sure you have the creator or performer give you a written, signed statement that assigns the copyright to you or, at the least, licenses you to use the work in your production.

In the case of music, as an example, if you want to use someone else’s work, you may have to obtain permission from the copyright holders: the composer, the publisher, the arranger, and the performer. Knowing whom to approach for permission and how to do it is often bewildering. Unfortunately, there is no simple solution to the problem. Requesting permission to use commercial sound recordings can be time-consuming, expensive and frustrating. Hollywood producers, for example, can easily pay thousands of dollars to obtain the rights to a released song. Nevertheless, if you are intent on using another person’s material, get permission in writing to do that. That way, you may never have to see the inside of a courtroom.

Another popular alternative is to use royalty-free music that is available from a number of suppliers and conveniently categorized with headings, such as Contemporary, Classical, Corporate or Industrial, Rock, Popular, etc. Once you obtain a license to use the library of music, you can reuse it as many times as you like for almost any purpose.

What Material is Available?

A number of other approaches, besides creating your own, original work or employing someone to create or perform material, can be used to solve your problem. For example, any intellectual property created before 1922 is out of copyright. Certain works created after 1922 are also out of copyright, but it can be difficult to know for sure without a search of Copyright Office records. In any event, you are free to video a Rembrandt painting, say, as long as the book that contains it was published before 1922. You can also perform a Beethoven sonata, as long as the recording or sheet music that you use was published before 1922.

The Copyright Act also includes a provision for “fair use.” Under this exception to copyright principles, you can use at least some of another person’s copyrighted material without permission if your purpose is for criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research. Tests for fair use include how much of the work is copied and whether the copyright holder will be harmed by your use of his material. A certain case involved a circus performer, whose 10-second performance of being shot out of a cannon and into a net was captured by TV news people and broadcast on the evening news. Yes, the purpose for broadcasting the act came under the heading “fair use — news reporting,” but once TV viewers saw the entire performance on the TV news, attendance at the circus was drastically reduced. Even a 10-second portion of a work can be considered too much under the fair use provision. Ask yourself whether your use of part of a song such as Dean Martin’s That’s Amore, in a documentary about penguins, will actually dissuade viewers from buying the original song. Unlikely. In fact, you can make an argument that more people will buy the record after seeing your movie.

Right of Privacy

Now that you understand what you can and cannot do regarding the works of others, it is time to discuss limitations on your own, original work. You have the right to videotape any subject—animal, mineral or vegetable—as long as the subject does not object, and as long as videotaping the subject matter does not subject you to criminal sanctions, such as child pornography or espionage laws. Remember, though, that a private citizen has the right to be left alone. If you sneak into a person’s backyard and videotape the occupants of the house through a window, you are likely to be sued by the person or persons you videotaped. You may even be arrested. People who are in their own home, in a motel room, or in a bathroom have a great expectation of privacy.

On the other hand, if a person is well known as a politician, say, or a sports figure, a rock star, a movie actor, or a hero of any other description, he is entitled to a lesser degree of privacy than a non-celebrity, private citizen has. The more famous the person, the less right of privacy he has. Famous celebrities will be the first to admit that they have almost no right of privacy.

Similarly, if a private citizen shows up at a parade or a football game or a protest march, he has put himself in a public place and should not expect the same degree of privacy that he has in his home. Sometimes, a person happens to be at a location in which a newsworthy event, like a fire, a hurricane, a bridge collapse or a police shoot-out occurs. In those cases, even though the person did not intentionally seek publicity, he still may have forfeited his right of privacy, due to circumstances beyond his control.

If a small group of people happens to be at your daughter’s dance recital or confirmation at your church, they may not expect to be videotaped. Do not let your camera linger on those bystanders for more than a few seconds. Do not single them out, especially if they are doing something impolite or inappropriate that would subject them to ridicule.

If you do not know whether the person’s appearance qualifies as a public one, it is

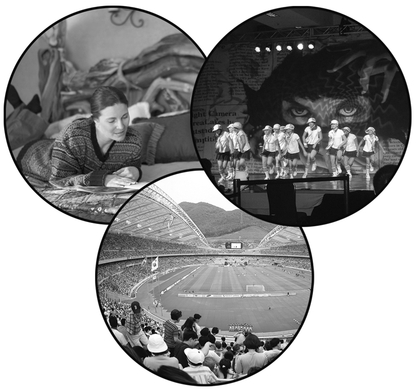

Figure 69-4 Different locations have different privacy expectations. In between these places lie gray areas. The only way to protect yourself for sure is to have talent and location releases.

best to obtain a photo or talent release from that person. Always carry a few of them in your camera bag. Sadly, many wonderful, hilarious performances that would otherwise appear on America’s Funniest Home Videos or on Candid Camera cannot be aired on TV because the subjects did not sign a talent release giving permission to the producer to show their image.

Conclusion

Many legal pitfalls await a videographer, but if you keep in mind the balance between the copyright and privacy rights of others and your constitutional right of free speech (or free videotaping), you will sense, if nothing else, when to call a lawyer.