Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 330

aoeg

aoeg

adhesion adhesion

320-335 03171.indd 330 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 330

B

efore we go any further it is

important to point out that

“legibility” and “readability” are not

the same. Legibility is essentially

the measure of how easy or diffi cult it is to

distinguish one letter of a typeface from

another. This makes it a typeface design issue

rather than a typographic one, a subtle but

important diff erence. Designers generally

accept the technique that underpins the

creation of legible typefaces: that they should

not try too hard to draw attention to their

design or style. A reader should see the words

fi rst and not get distracted by the typeface itself.

The most legible typefaces tend to have

prominent features such as large x-height and

large counters, along with individual character

shapes clearly defi ned from one another

and therefore easily recognizable. (X-height

should not be too large, however, because

too little contrast [230] between x-height

and length of ascenders and descenders can

compromise legibility.) For this reason—

relative simplicity of character shapes—some

argue that sans serif fonts are more legible than

serif fonts.

It really depends on the individual typeface

rather than the classifi cation, and on the

intended purpose of the typeface, whether for

signage, display, text and so on. Weight plays

an important part, too; ultra light or black/

heavy faces are often not as legible as those

with a roman or book weight, especially when

set at smaller point sizes. Research has shown

that the optimum stroke width for legibility is

around 18 percent of the character’s x-height.

It is also important to bear in mind that

the vast majority of letters in running text are

lowercase (332), so diff erences in lowercase

character shapes and openness of counters

have the greatest eff ect on legibility. Lowercase

characters vary much more in shape between

typefaces, not just because of proportions

but also because of characters such as the

double-storey a or g, which help distinguish

those characters from the similarly shaped

o, e, q, and so on.

In contrast to legibility, readability falls on

the designer’s shoulders and doesn’t neces-

sarily depend on typeface legibility. Reading

should ideally take no additional eff ort beyond

actually recognizing and comprehending what

Legibility and Readability

Certain letterforms are more distinctive

in serif typefaces. On the left, Garamond.

On the right, Franklin Gothic.

A double-storey lowercase

character such as an a or g helps to

improve legibility between other

similarly-proportioned characters.

How x-height eff ects legibility: Typefaces with

large x-heights often appear larger set at the

same size as typefaces with smaller x-heights.

Tiempos Text 24 point Baskerville 24 point

Tiempos Text 24 point Baskerville 32 point

320-335 03171.indd 330 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 331

320-335 03171.indd 331 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Typography Terminology and Language

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 331

the words say and mean. Once an individual has

learned basic reading skills, the act of reading

becomes a series of automated responses to the

arrangement of the characters and words on the

page or screen. It is up to the designer to make

decisions that will create good readability.

It is not a given that a highly legible typeface

will produce highly readable text. One of the

more common mistakes made when selecting a

typeface is choosing one designed for a purpose

other than that which the designer has in mind.

For example, typefaces designed specifi cally for

signage will generally be highly legible, but this

doesn’t mean they work well as a text face. Take

the time to fi nd out about a typeface’s origins

and intended use, and experiment with dummy

settings at various sizes to see how a face reads

before making a committed choice.

Typeface choice aside, the combination of

measure plus word-count-per-line is proba-

bly the dominant factor that aff ects readability.

A character count (including spaces) that falls

somewhere between fi fty-four and eighty per

line of text tends to be the most satisfactory for

readability. This range works for pretty much

every typeface suitable for use as running text,

with the typeface (and any restrictions imposed

by the layout itself) infl uencing decisions about

point size and measure.

Also, take into account subject matter of text

when deciding how a measure will infl uence

readability. For example, a long read such as a

novel can support the use of a wider measure

as the reader will relax into a “reading rhythm,”

allowing him or her to scan longer lines of text.

In addition, longer measures allow letter spacing

(334) to be set more evenly, further improving

readability. On the fl ip side, text appearing in a

reference book or newspaper benefi ts from being

set over a shorter measure in a layout utilizing

two or more columns for easy, quick scanning of

bite-sized pieces of information.

A designer’s job will become even more chal-

lenging as the quantity of information and noise

increases during the twenty-fi rst century. Those

who possess a broad typographic understanding

will best meet the communicative and cre-

ative challenge, especially during a time when

people know the diff erence between one font and

another—and which ones read better or worse

with software’s default 120-percent leading.

A designer’s job will become even more challenging as the quantity of information and noise increases

during the twenty-fi rst century. Those who possess a broad typographic understanding will best meet the

communicative and creative challenge, especially during a time when people know the diff erence between

one font and another—and which ones read better or worse with software’s default 120-percent leading.

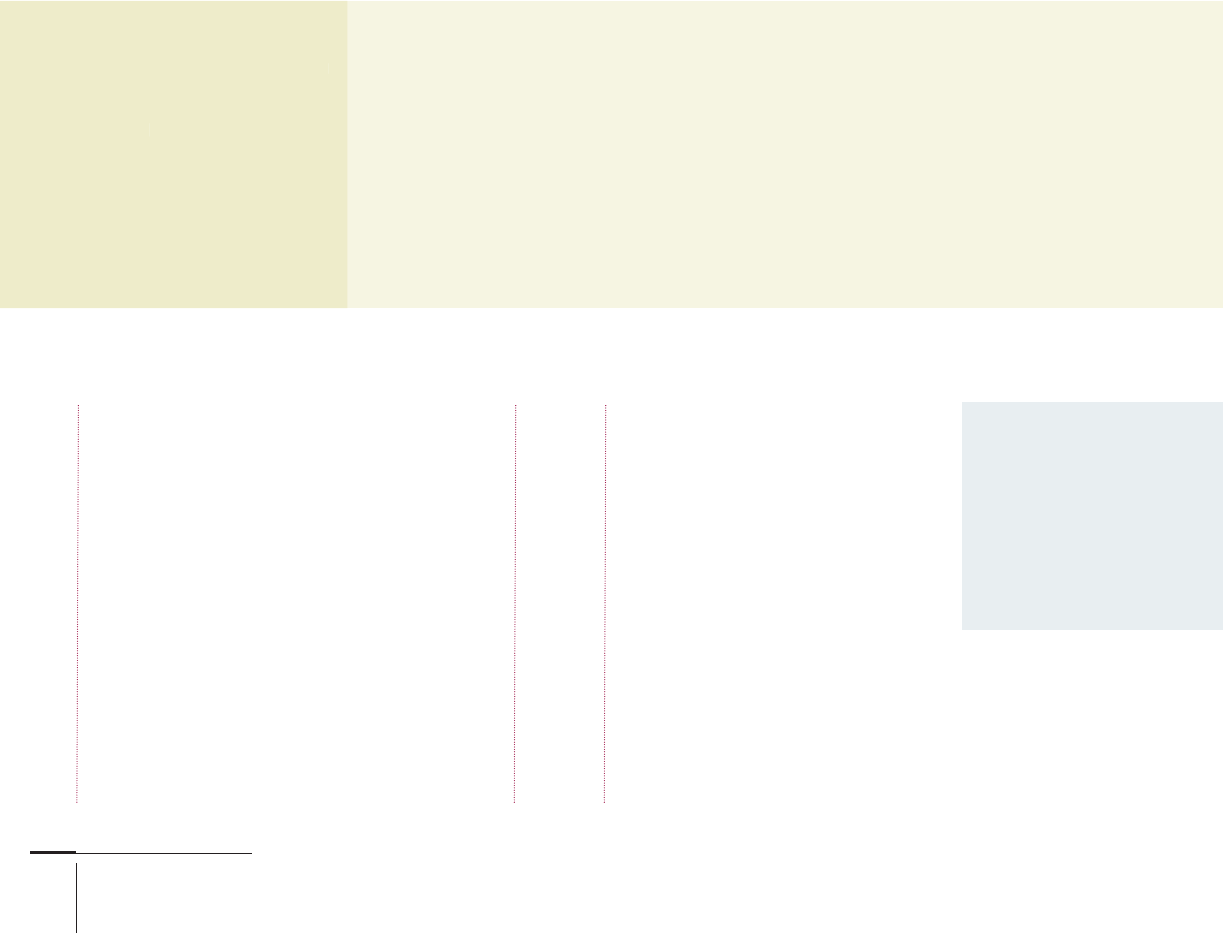

The short measure shown to

the left is ideal for shorter

sections of bite-sized infor-

mation; it displays excellent

readability properties and

is perfect for newspapers or

reference books. The longer

measure below would work

well in a novel, but read-

ability is not as good over

just four lines of text.

320-335 03171.indd 331 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 332

320-335 03171_C2.indd 332 10/13/11 5:02 PM

332

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 332

“A de

s

will b

e

more

c

as th

e

infor

m

Certa

i

such

a

T app

e

when

“

“

A

A

A

d

d

e

e

s

w

w

w

w

i

l

l

l

b

b

e

m

m

m

m

o

o

r

e

e

c

a

a

a

s

s

t

t

h

h

e

i

i

n

n

n

f

f

o

o

r

r

m

C

C

C

e

e

r

r

t

a

a

i

s

s

u

u

u

c

c

h

a

T

T

T

a

a

p

p

p

e

w

w

w

h

h

h

e

n

n

332

Typography, Referenced

A designer’s job will become even more

challenging as the quantity of information

and noise increases during the twenty-

fi rst century. Those who possess a broad

typographic understanding will best

meet the communicative and creative

challenge, especially during a time when

people know the diff erence between one

font and another—and which ones read

A DESIGNER’S JOB WILL BECOME

EVEN MORE CHALLENGING AS THE

QUANTITY OF INFORMATION AND NOISE

INCREASES DURING THE TWENTYFIRST

CENTURY. THOSE WHO POSSESS A BROAD

TYPOGRAPHIC UNDERSTANDING WILL

BEST MEET THE COMMUNICATIVE AND

CREATIVE CHALLENGE, ESPECIALLY

DURING A TIME WHEN PEOPLE KNOW

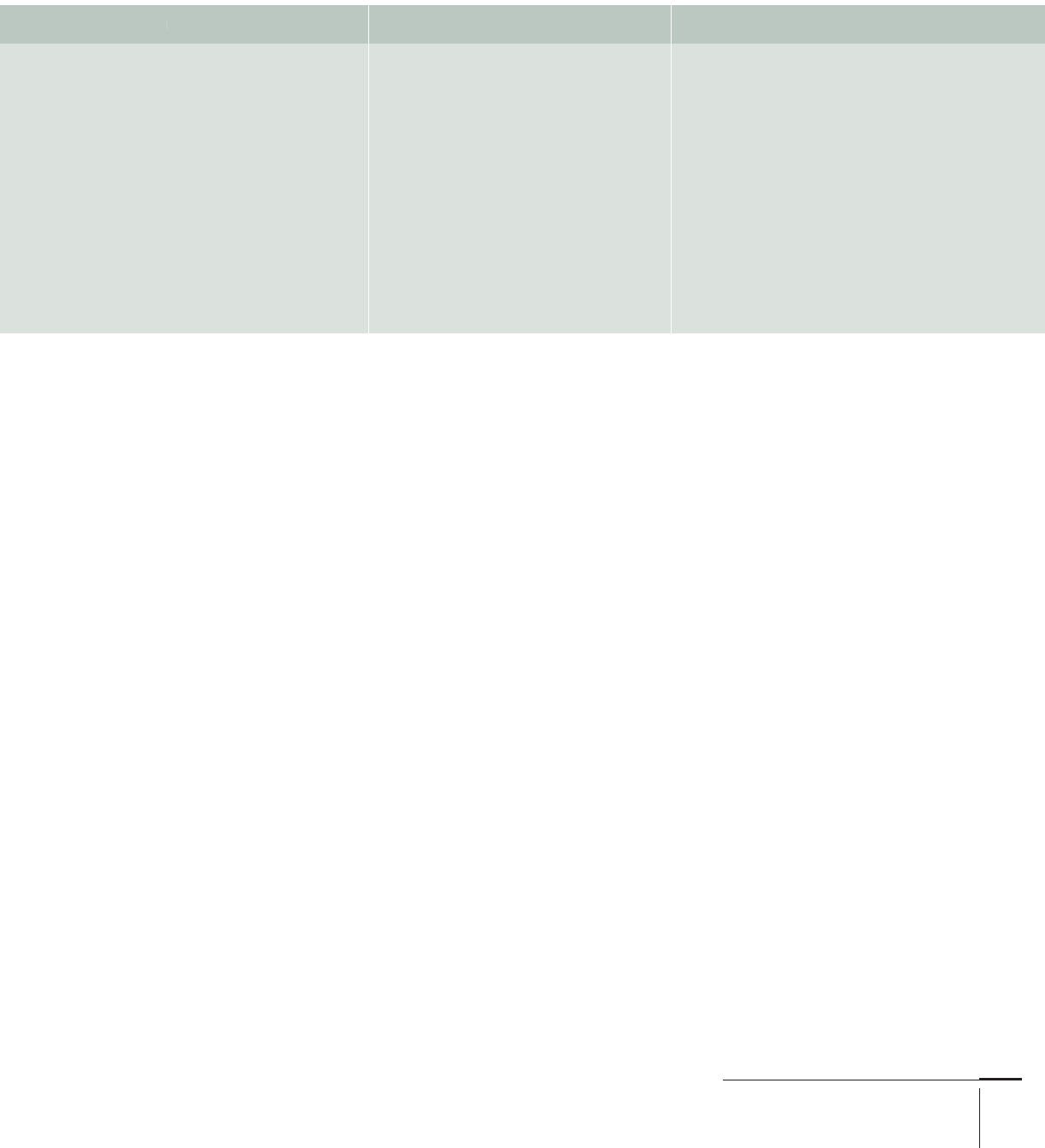

Running text set in CAPS

is harder to read because

the shape of words set

in lowercase appear as

remembered word images

to a seasoned reader.

Words set in CAPS appear

simply as rectangles.

Optical alignment

allows certain

characters that

would otherwise

appear as slightly

indented to nudge

into the margin,

where they are

referred to as

“hung” characters.

Upper and Lowercase

Uppercase characters provide emphasis and stress

importance, whether at the start of a sentence or when

used in a headline. Caps are LOUDER than lowercase

characters and can visually SHOUT to the reader.

However, on the readability (330) front, uppercase

text that extends beyond the length of the average

headline is not as easy to scan, drastically reducing

reading speed.

This is because a reader cannot recognize words set

in uppercase as quickly; the word is read letter by letter

rather than as a single image. This point does not apply

to new readers, for example young children, but rather

to seasoned readers who have learned to recognize word

images in the same way a computer caches information.

A word set in uppercase always appears as a rectangle

with varying length depending on number of characters,

while a mixture of upper- and lowercase gives every

word its own unique shape. This ties in neatly with

the notion that lowercase characters have the greater

legibility (330).

Beyond this little snippet of typographic science,

the use of upper- and lowercase characters simply

comes down to style, limited only by a designer’s skill

and imagination.

“A designer’s job

will become even

more challenging

as the quantity of

information…

Certain characters,

such as the uppercase

T appear slightly indented

when positioned…

“A designer’s job

will become even

more challenging

as the quantity of

information…

Certain characters,

such as the uppercase

T appear slightly indented

when positioned…

320-335 03171_C2.indd 332 10/13/11 5:02 PM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 333

320-335 03171.indd 333 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Typography Terminology and Language

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 333

Flush Left Flush Right Center

A designer’s job will become even

more challenging as the quantity

of information and noise increases

during the twenty-fi rst century. Those

who possess a broad typographic

understanding will best meet the

communicative and creative challenge,

especially during a time when people

know the diff erence between one

font

and another—and which ones read

better or worse with software’s

default 120-percent leading.

A designer’s job will become even

more challenging as the quantity

of information and noise increases

during the twenty-fi rst century. Those

who possess a broad typographic

understanding will best meet the

communicative and creative challenge,

especially during a time when people

know the diff erence between one

font

and another—and which ones read

better or worse with software’s

default 120-percent leading.

A designer’s job will become even

more challenging as the quantity

of information and noise increases

during the twenty-fi rst century. Those

who possess a broad typographic

understanding will best meet the

communicative and creative challenge,

especially during a time when people

know the diff erence between one

font

and another—and which ones read

better or worse with software’s

default 120-percent leading.

Alignment

There are only four basic alignment choices—fl ush left,

fl ush right, justifi ed, and centered—and most people

understand these terms regardless of their profession.

However, good reasons exist for choosing one option

over another, as well as for not mixing the options, all of

which link back to readability (330) and aesthetics.

Flush-left text means a consistent vertical alignment

down the left side of a column such that each new line

of text starts from the same point. This helps improve

readability. Flush-right text aligns at the right side of a

column; this lessens readability for long passages of text,

but can work for shorter paragraphs that range against

the right side of an image or page edge in a layout.

Beware of mixing fl ush-left and fl ush-right alignment in

any given text chain. It never works and will ruin a pro-

fessional layout.

Justifi ed text, which aligns down both sides of a

column, is better suited to text set over wider measures.

To force the words in each line of text to justify, the

word and letter spacing (334) gets adjusted across the

full measure, occasionally introducing awkward spaces

between longer words. It is sometimes possible to man-

ually adjust the spacing to create aesthetically pleasing

typography, but often editing the text results in the

greatest improvement.

Centered text arguably provides the lowest level

of readability, so it is best reserved for short, isolated

paragraphs of text set over a fairly narrow column.

Inappropriate use of centered text in a layout is a good

indicator that a designer is not an experienced typog-

rapher. One of the most common mistakes is mixing

centered headlines with fl ush-left text. On the other

hand, a centered headline works with justifi ed text as

long as headline length and text measure balance well.

Optical alignment

Following from the basic points made above, aligning

text along a vertical edge is not always as straightfor-

ward as it may seem. Certain characters, such as the

uppercase (332) T or W, appear slightly indented when

positioned at the start of a line. The same applies to

punctuation, for example quotation marks. Adjusting

these can achieve perfect optical alignment.

The off ending characters must be “hung,” meaning

repositioned slightly to the left of the point of vertical

alignment (if the text is fl ush left). The degree of

adjustment varies from typeface to typeface and

depends on the point size. The eff ect is less apparent

at smaller point sizes, and the kerning (334) pairs

built into a font deal with the problem in most

circumstances. Page layout applications such as Adobe

InDesign have built in functions such as optical margin

alignment that get applied automatically.

320-335 03171.indd 333 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 334

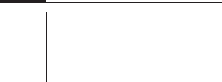

Ave Aw Ay Ca Cl Ci Ey Ko Ky

Ma My Ov Ow Ox Oy Pa Pe Pi Pj Po Pr

Ra Re Ri Ro Ru Rw Ry n’t i’l

Te Th Ti To Tr Ts Tu Tw Ty

Va Ve Vi Vo Wa We Wi Wo Wu Wy

Xa Xe Xi Xy Ya Ye Yi Yo Za Ze Zi Zo Zu

320-335 03171.indd 334 9/23/11 2:34 PM

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 334

Typography, Referenced

Letter spacing

This should eff ectively be invisible. The only spaces that

should register in a reader’s mind are those between

words. The aim of kerning, the typographic term for

letter spacing, is to achieve even visual spacing between

all characters in all words of a text. No letter space

should appear so large as to be mistaken for a word

space or look larger than any of the neighboring spaces.

Type designers build into digital fonts what are

called kerning pairs to alleviate the problem of

unsightly letter spacing between pairs of characters

that sit together awkwardly. The illustration below

shows some of the more common problem-causing

pairs. A well-designed typeface eliminates through

the shape of its letterforms the need for an excessive

number of kerning pairs, with the best letter spacing for

optimum readability (330) between characters set auto-

matically for any given font.

This auto-kerning works best for fonts within the

10- to 14-point range, known as the optimal size range.

Type set below 10 point or above 14 point more likely

will need some manual kerning. Point sizes below 10

may look like they are closing up and may need space

added. Point sizes above 14 create the impression that

the character spacing is too large, with the eff ect of

increasing as point size increases.

Space can be added or subtracted uniformly for all

lines of text in a layout by adjusting tracking, a facil-

ity built into Adobe InDesign, QuarkXPress, and other

layout programs. Adjust kerning incrementally to

achieve the best results, and watch out when ligatures

(single characters composed of two characters paired

together in certain combinations) are involved. If the

kerning on either side of a ligature does not look right,

choose between further kerning or replacing the liga-

tures with standard characters using the appropriate

functionality of your design application.

There are many kerning pairs that often require

attention, especially when used at larger point sizes.

Some may not seem familiar to you, but bear in mind

that kerning pairs in your native language may diff er

from those commonly used in another language.

320-335 03171.indd 334 9/23/11 2:34 PM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.