Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 46

030-051 03171.indd 46 9/22/11 4:25 PM

46

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 46

A well-spaced paragraph of foundry type, from the

Encyclopedie of 1754 demonstrates how an even

typographic texture makes a text readable even with

variations in the density of some letters, the horizontal

alignment on the x-height, and inconsistent inking

or pressure. In the digital versions, the top paragraph

is spaced to exactly match the letterpress example,

and the bottom one makes full use of InDesign’s

composer and spacing tools. The diff erences in texture

are modest. Both paragraphs have some rivers of

white. If anything, the lower paragraph is slightly

more cramped and overcompresses the space around

punctuation. The metal type preserves the minimum

amount of space to the left and right of letters, whereas

the digital version overcompresses some spaces.

A

lthough display typefaces (213)

are relatively straightforward

to space, spacing text typefaces

(212) can be extremely time-

consuming. It is not easy to describe how in

a few sentences, but careful examination of

good examples points to one basic rule and a

fundamental set of relationships. Here’s the

rule: The optimum average space between

typeforms depends on the relationship of the

vertical-stroke width and the width of the

counters in two-stroke forms (such as the n

and b), modifi ed by the optical size for which

the typeface is intended. Outside a relatively

narrow range, the x-height in relation to

the width of the stroke is also a factor. We

can easily imagine a system of interlocking

ratios that change with the modifi cation of

one of these variables.

Of course, this approach does not directly

answer how much space to leave between

letters; it only indicates a series of relation-

ships. The trick is to remember that a text

typeface is spaced for paragraphs, not indi-

vidual letter combinations. In other words,

the designer should aim for a specifi c density

in the texture. Well-spaced paragraphs tend

to have a minimum of a stroke width’s white

space (228) between round letters and pro-

portionately more between straight ones.

030-051 03171.indd 46 9/22/11 4:25 PM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 47

030-051 03171.indd 47 9/22/11 11:52 AM

47

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 47

T

he demand for typefaces with

extended character sets has

been growing steadily for many

years. Operating systems and

application interfaces must be capable

of displaying many languages. That

and the internationalization of publi-

cations as well as brands for products

and services means larger typeface

character sets. Today, a typical custom

typeface for a big brand may easily

extend to several thousand charac-

ters and span fi ve or more scripts.

Typefaces bundled with operating

systems and applications and custom

typefaces for brands are expected to cover

more than one script—and often three or

more. The current minimum for interna-

tional brands covers the wider European

region: Cyrillic, Greek, and extended

Latin. Increasingly character sets also

cover Arabic, Hebrew, and Indian scripts.

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Character Expansion

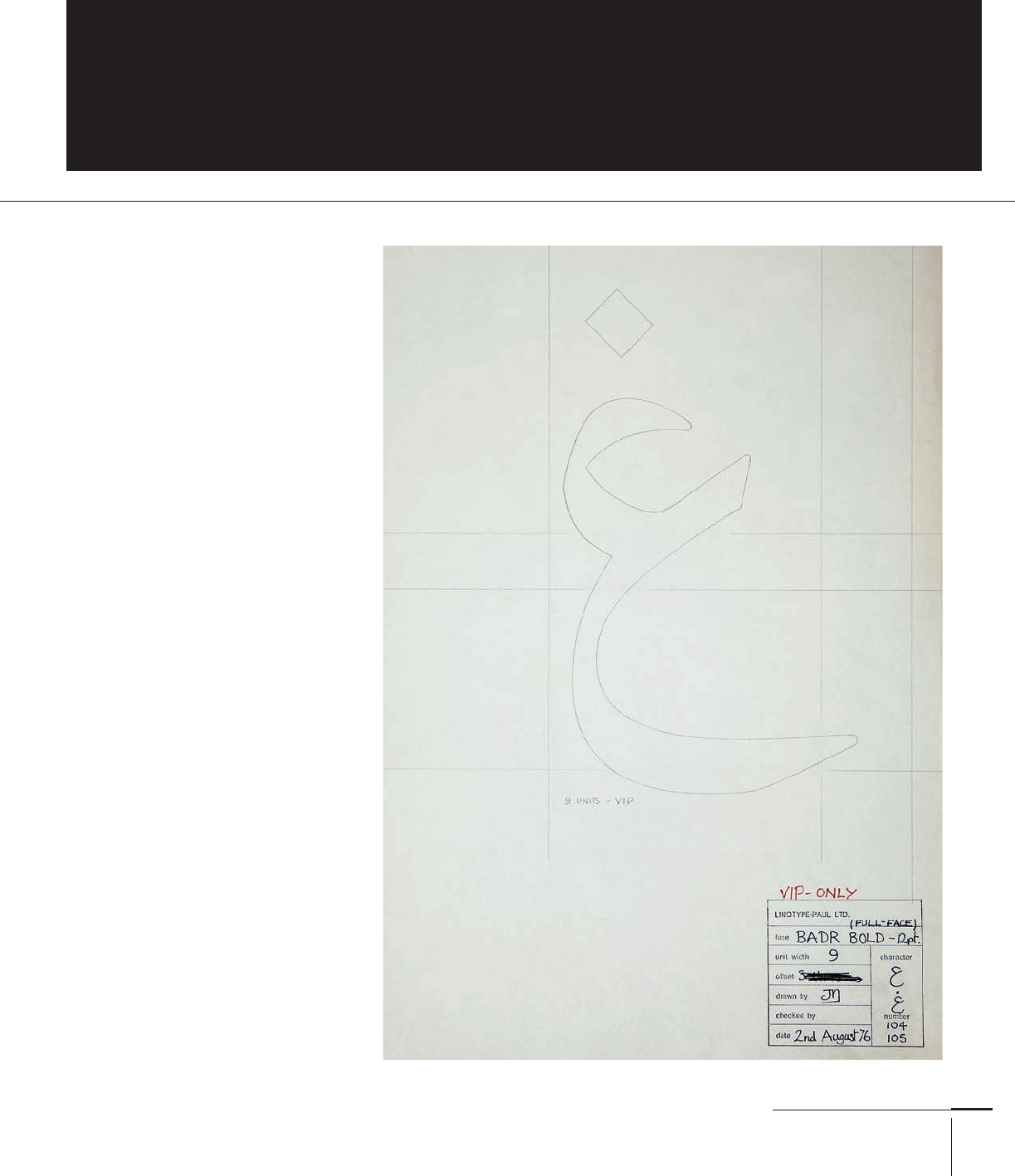

This drawing for the

Linotype system from

shows a typeface still

in use in other formats

developed by a team of

designers. The type-making

process and the costs asso-

ciated mean that drawings

such as this encapsulate

signifi cant knowledge about

the typographic script.

030-051 03171.indd 47 9/22/11 11:52 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 48

030-051 03171.indd 48 9/22/11 4:28 PM

48

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 48

Typeface design is linked to the limitations

of the typesetting environment. Most subsets of

the Latin script (simple, alphabetic, left-to-right

models) do not push the limits of a system based

on a simple structure of sequential rectangular

units. But this approach is strained by multi-

ple diacritics and collapses when the shapes do

not fi t in boxes or change shape in algorithmi-

cally complicated ways. As a result, typesetting

systems have had to be adapted, extended, and

even rewritten to accommodate the complexi-

ties of non-Latin scripts. Although designers do

design Latin typefaces with typesetting tech-

nology in mind, in many cases of non-Latin

scripts, they have had to modify their designs

quite drastically just to get the shapes to render.

In general, non-Latin scripts do not have the

full profusion in styles that arises from a com-

petitive publications market, as well as a culture

of constant text production. (It’s no surprise

that the language of display typography fi rst

developed in nineteenth-century Britain during

the Industrial Revolution.) This is gradually

changing, largely under the pressure of inter-

national branding and localized publications.

We are beginning to see rapid growth in new

typefaces for non-Latin scripts, and a growing

interest by typeface designers.

Three typeforms from the

Markant typeface exemplify

how similar proportions and

features can be integrated

within the constraints of

each writing model (italic

and upright Latin and Greek).

The Capucine family by Alice Savoie integrates

Latin and Greek text in magazines without

disrupting the texture of the paragraph. Despite

this, the typeforms for each script are developed

with sensitivity and do not appear derivative.

030-051 03171.indd 48 9/22/11 4:28 PM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 49

030-051 03171.indd 49 9/22/11 11:53 AM

49

Type Design and Development

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 49

Non-native Speakers

Can a non-native speaker design a

typeface for a language? A typeface

arises in response to a client’s brief,

which taps into wider design problems.

For example, many of the con-

ventions surrounding newspapers

apply regardless of the market; the

constraints on the typographic spec-

ifi cation can be deduced from the

general qualities of the script and the

language. Can the typeface include

hyphenation? How long are the words

and sentences? With what range

of word lengths? What is the edito-

rial practice in the region in terms of

article structure, levels of hierarchy

(), and headline composition?

Only after establishing the typo-

graphic environment can we examine

the written forms of the language

and the tools that have determined

the key shapes. In this matter most

scripts other than the Latin (and to

some degree Cyrillic) maintain a close

relationship between writing and

typographic forms. Writing exercises

and a structural analysis of examples

can help the designer develop a feel

for the script before reading the words.

More importantly, when working

with a language or alphabet that is

not his or her own, analysis of the

script’s structure and the relationship

between mark-making tools and type-

forms can help the designer to develop

criteria for evaluating quality.

Typographic history is well popu-

lated with designers excelling in the

design of scripts they could not read.

Encouraging students to address the

complicated design problems inherent

in non-Latin scripts is not only a way

of enriching the global typographic

environment, but also is a superb

means of producing designers who

can tackle a higher level of diffi culty

in any aspect of their design.

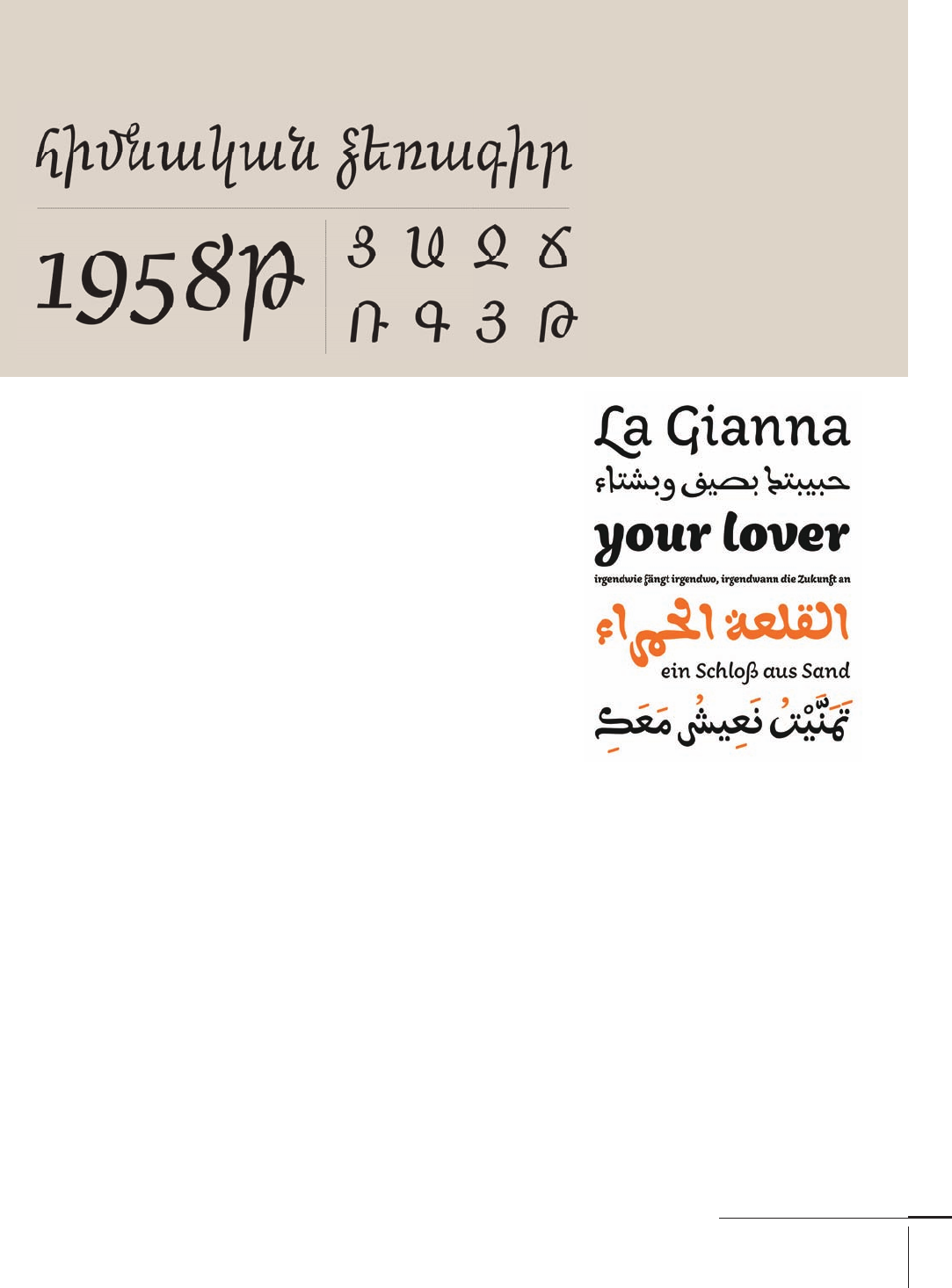

This is the italic style from Khajag

Apelian’s Arek typeface, a new

Armenian and Latin design and one of

the fi rst to introduce a more fl owing

style to the Armenian italic, hinting

at the scope of typographic invention

possible in non-Latin scripts.

Titus Nemeth’s Aisha typeface is

a new Arabic that draws on North

African infl uences and tradi-

tions. This area has been relatively

ignored by recent developments,

but promises a wealth of material

that can inform new designs.

030-051 03171.indd 49 9/22/11 11:53 AM

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 50

030-051 03171.indd 50 9/22/11 11:53 AM

50

Typography, Referenced

Text

Job:03171 Title:Typography Referenced (Rockport)

Page: 50

E

xcellence in typeface

design can be diffi cult

to identify without

the perspective of

long-term review. Typefaces can

become prominent because they

embody a strong brand well or

capture the moment in terms

of their visual style. Typefaces

for important publications or

services are typical of the fi rst

kind (think Cheltenham [] for

the New York Times headlines, for

example) and Excoff on’s Mistral

of the second. Other typefaces

may become successful through

their wide use, even as designers

complain about their ubiquity.

(Times [] is a great example. It

has become, arguably, a meta-

typeface, existing in countless

versions and adaptations, but

its typographic feel is instantly

recognizable worldwide.) But

a capacity for discovery and

invention characterize the fi eld of

typeface design.

TYPE DESIGN AND DEVELOPMENT

Familiar Shapes,

New Interpretations

A typeface is a product of the applied arts: It embodies functionality and usability and has intrinsic

value through its utilization. On the most basic level, it allows encoding of textual meaning, but on

a higher level it allows expression of values such as association, style, identity, diff erentiation, and

beauty. This is the least tangible aspect of a typeface, but the one that most motivates designers.

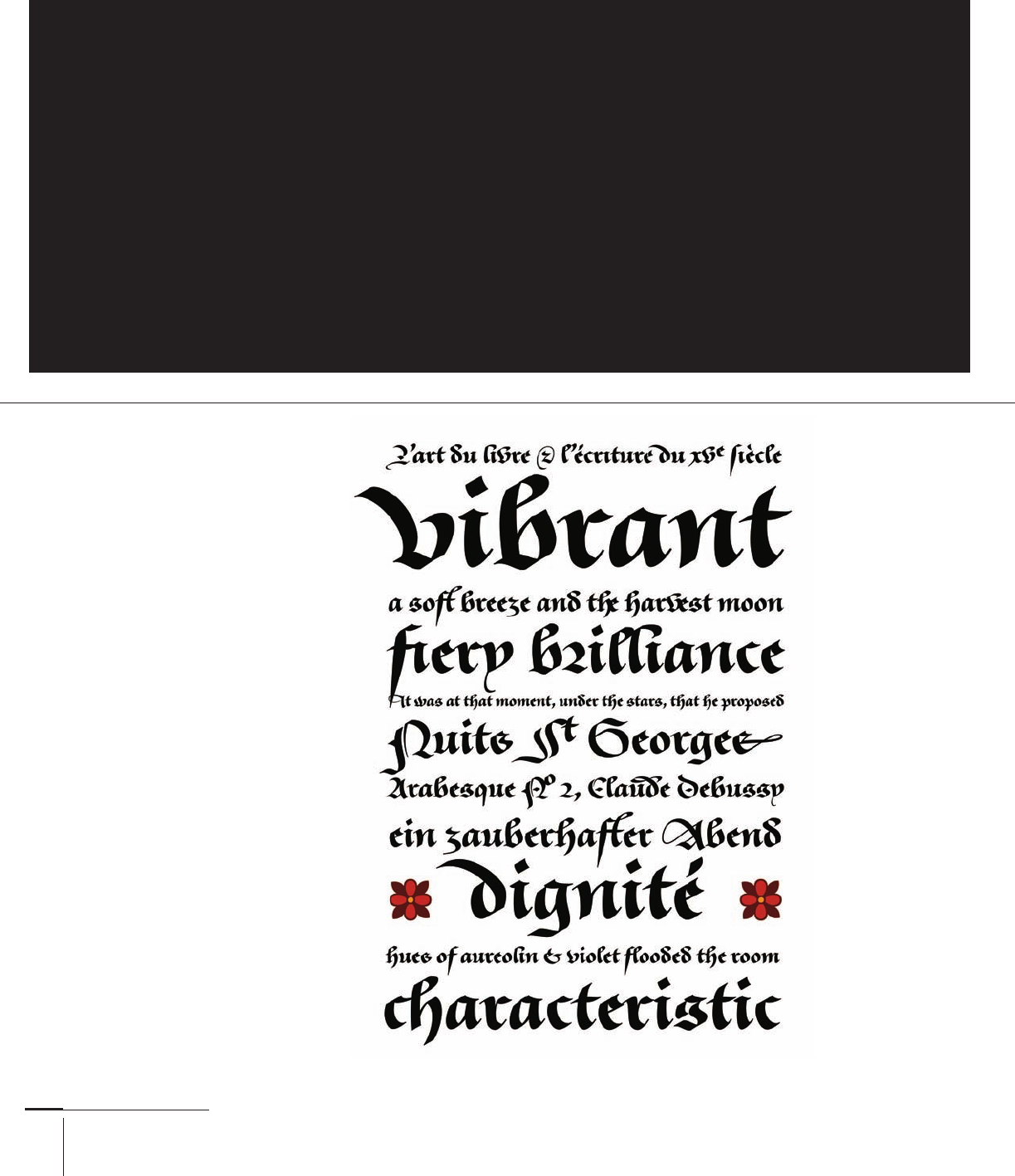

Tom Grace’s Givry is a

fresh take on the bâtarde

fl amande from the fi fteenth

century. This black-

letter is lesser known than

other heavy, pen-written

styles of the period but is

typographically more inter-

esting for the potential

of its fl owing strokes.

030-051 03171.indd 50 9/22/11 11:53 AM

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.