CHAPTER 5

![]()

Bordeaux

The Gironde has been for a long time France’s leading wine département, less for the extension of its vineyards (around 150,000 hectares) than for the variety and care in their cultivation; for its wine-making skills, and the character and remarkable qualities of its products; for the low prices of the inferior ones and the astronomical price for the best; and finally for the vast size of the domestic and foreign wine trade.

—Jules Guyot, 1868, 1:429

THE ENGLISH OCCUPATION of Bordeaux between 1152 and 1453 led to a major growth in the wine trade, and imports peaked at 102,724 tons, or about 900,000 hectoliters, in 1308–9.1 Trade declined once more after the loss of the city and fluctuated over the centuries according to the political situation between the two countries. From the late seventeenth century, duties on French wines were set at higher levels than on those from Portugal and Spain and resulted in British consumers, in the words of David Hume in 1752, being obliged to “buy much worse liquor at a higher price.”2 Although French wines of all descriptions accounted for less than 10 percent of the British market as late as the 1850s, a relatively high proportion of Bordeaux’s best wines were exported to Britain, to be consumed by a very small group of wealthy consumers.

The long history of commercial relations between many British ports and Bordeaux, together with the Gironde department’s large and varied production of wines, made the region a potential source of fine and commodity wines after the reduction in duties in 1860. This chapter begins by examining the long-run changes in wine production and trade during the nineteenth century and the organization of wine production. After a period of prosperity that lasted from the mid-1850s to the early 1880s, there followed three decades of depression caused by the appearance of vine diseases, the decline in reputation of both fine and beverage wines, and overproduction in the French market. Fine wine production in the Gironde was concentrated in the region of the Médoc, and the production on the large châteaux contrasted with that of the thousands of small, family vineyards found in the region. Information problems for consumers of fine wines were reduced by the 1855 classification, but the growth in market power and economic independence of the leading estates was checked in the late nineteenth century, partly because of the expenses associated with vine diseases, and partly by the decline in wine quality and collapse in the reputation of their wines among consumers. Finally, small growers successfully used their political voice to achieve legislation to establish a regional appellation, which limited to wines of the Gironde the right to carry the Bordeaux brand.

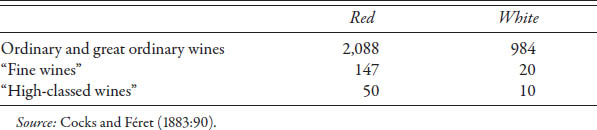

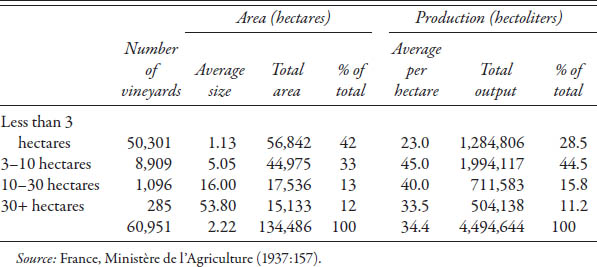

TABLE 5.1

Wine Production by Quality in Bordeaux, 1870s (thousands of hectoliters)

CLARET, TRADE, AND THE ORGANIZATION OF PRODUCTION

Bordeaux, unlike Jerez or Porto, was itself a major production center for both fine and commodity wines. Red wine represented almost 70 percent of the Gironde’s wine output in the early 1870s, and 86 percent of fine wines (table 5.1). Fine red Bordeaux wines were blended from a variety of grapes. According to one wine specialist, even today “this is only partly because Merlot and Cabernet are complementary, the flesh of the former filling in the frame of the latter. It is also an insurance policy on the part of growers in an unpredictable climate.”3 The exact proportions of cabernet sauvignon, cabernet franc, and merlot used varied according to the local terroir and the nature of the vintage. There were also longterm changes in the grape varieties used, especially among commodity producers, and the historian Philippe Roudié argues that the appearance of powdery mildew in the 1850s reinforced the differences between the grand crus and petits vins, as the growers in the less favorable areas for wine production uprooted the merlot and planted malbec (red), enrageat, and sémillon (white), all varieties that were more disease resistant and produced higher yields.4

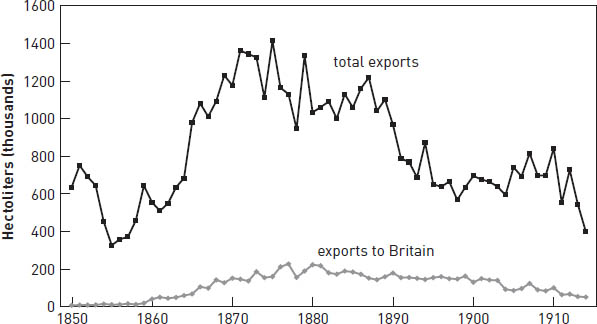

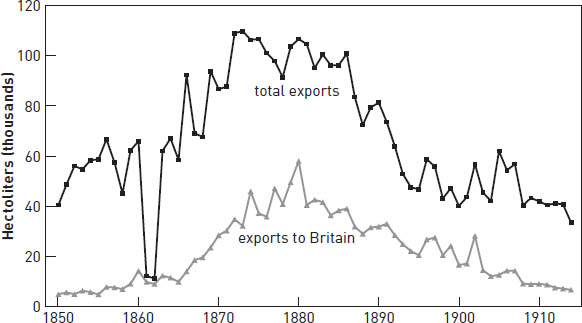

French trade statistics provide figures for wine exports from Bordeaux both in bottles and in barrels (the Bordeaux tun contains four hogsheads of 220–250 liters each). The export figures for bottles serve only as a very rough indicator for fine wines, as an unknown quantity of high-quality young wine was exported in casks to be matured and bottled at its destination. There could also be significant price variations between the different wines that were exported in bottles. While recognizing these limitations, figures 5.1 and 5.2 provide a reasonably accurate picture of the long-run changes in the exports of fine and ordinary table wines. In particular, figure 5.2 shows that Britain was the major market for fine wines in the second half of the nineteenth century. Even at the end of the period, when exports had declined significantly, Ridley’s believed that consumption of the “better class Wines” per capita was as great in England as it was in France.5 Exports of commodity wines in barrels to the United Kingdom increased from less than 20,000 hectoliters in the 1850s to ten times this quantity in the late 1870s. Exports of both categories to the Britain peaked in 1880 and then started to decline, the fall being much greater with bottled wines.

Figure 5.1. Bordeaux wine exports in barrels, 1850–1914. Source: France. Direction Générale des douanes (various years)

Figure 5.2. Bordeaux wine exports in bottles, 1850–1914. Source: France. Direction Générale des douanes (various years)

Wine exports to other markets peaked earlier, with those in barrels doing so in 1875, and those in bottles in 1866 and 1873. Wine shortages and higher prices in France encouraged the development of viticulture in some of Bordeaux’s traditional markets in the New World, and this continued when prices started falling in the 1890s, as foreign producers sought refuge behind protective tariffs.

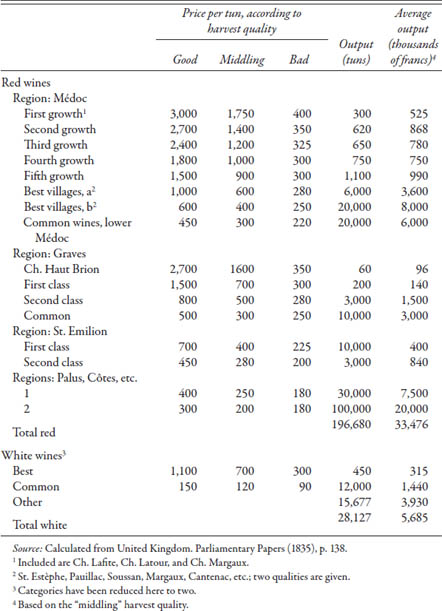

The growth in demand for wine in the mid-nineteenth century led to the area of vines in the Gironde increasing from 133,000 hectares in the early 1840s to 188,000 by the 1870s, when phylloxera and lower prices caused it to decline once more to 138,000 hectares by the early twentieth century.6 The basis of Bordeaux’s reputation rested on the production of fine wines from less than one hundred growers that represented only a small part of the Gironde’s total production. As late as 1924, the 285 growers with more than 30 hectares (some of which produced commodity wines) were responsible for only 11 percent of the region’s output (table 5.2). On the famous large estates, the vines were almost never leased and the owners managed directly the production of their own grapes. Suitable incentives were required for laborers to diligently carry out those tasks in the vineyard that might affect the future productive capacity of the vine or influence the characteristics of the harvest. The preferred contract used skilled workers (prix-faiteurs) who were responsible for all the operations on a fixed area of vines, which in the Médoc was usually slightly less than 3 hectares. The contract stipulated a variety of rewards, both formal and informal, to compensate workers, including accommodation, heating, cheap wine, a small garden, and a salary.7 In addition to secure employment, the prix-faiteurs organized the work themselves, and they were given enough free time to tend their own vines or earn extra wages by doing piecework. The mutual benefits of this type of contact can be seen in the long, continuous employment of workers, with many prix-faiteurs on Château Latour, for example, having worked there for decades, and with a son following his father by being employed as a vigneron.8 By contrast, the more physical and nonskilled tasks on the estates were paid by piecework, and laborers could earn relatively high wages. The need for piecework increased significantly in the second half of the nineteenth century on account of vine disease, and this provided much-needed employment for local growers who had insufficient vines to keep themselves fully occupied.

TABLE 5.2

Farm Structure and Output in the Gironde, 1924

Small producers of commodity wines faced different problems from those of the large estates, namely, the need to reduce their exposure to a poor harvest or low prices. One possibility in the less prestigious wine areas of the Gironde was intercropping (joalles). There were two main types, les grandes, with rows of vines planted every 6–12 meters and cereals grown in the space between, and les petites, with vines planted closer together, every 3–6 meters and with legumes and forage crops sown.9 By the late nineteenth century, with phylloxera and mildew devastating their vines, some growers also turned to fruit trees.10 Wine yields were higher than those of fine wines, as the vines were found on relatively fertile soils and intercropping required the use of fertilizers.

THE 1855 CLASSIFICATION AND THE BRANDING OF CLARET

The most important vineyards, such as Château Margaux and Château Lafite, were well-known among British consumers of fine wines in the eighteenth century and enjoyed a considerable premium over lesser wines. Growers hoped to sell their wines about six or eight months after the harvest to the négociants in the Chartrons area of Bordeaux, who then matured and exported them. Growers therefore saved themselves the cost of racking the wine from its lees and losses caused by evaporation. The fine wines shipped in the early nineteenth century were very different from those later in the century. The fact that the grapes were not removed from their stalks during fermentation made the wines very hard and full of tannin. To overcome this they were blended, as André Jullien noted in 1816: “The wines of the first growths of Bordeaux as drunk in France do not resemble those sent to London; the latter, in which is put a certain quantity of Spanish and French Midi wine, undergo some preparations which give them a taste and qualities, without which they would not be found good in England.”11

This same author noted elsewhere that

The English houses at Bordeaux, immediately after the vintage, purchase a large quantity of the wines of all the best vineyards, in order that they may undergo la travaille a l’Anglaise. This operation consists in putting into fermentation part of the wines during the following summer, by mixing in each barrel, from thirteen to eighteen pots of Alicant or Benicarlo, or the wines of the Hermitage, Cahors, Languedoc, and others; one pot of white wine, called Muet (wine whose fermentation has been stopped by the fumes of sulphur) and one bottle of spirits of wine. The wine is drawn off in December, and then laid up in the chais (cellars) for some years. By this operation the wines are rendered more spirituous and very strong, they acquire a good flavour, but are intoxicating. The price likewise is increased.12

When this custom ended is difficult to establish, as contemporaries often simply repeated in their accounts what earlier authors had written. Penning-Rowsell notes that the seventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica (1842) suggests it was still common, but it seems likely that tastes did alter around the mid- nineteenth century.

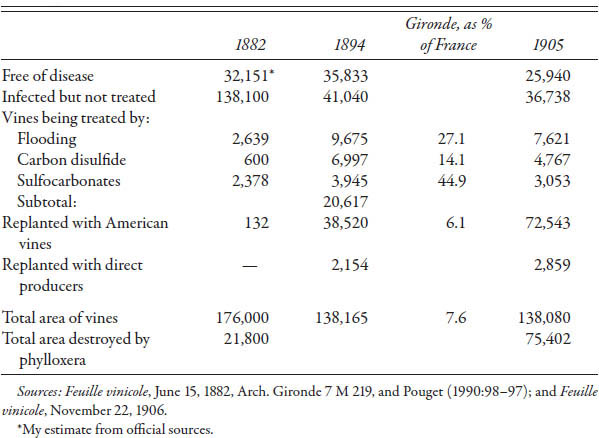

Producers and consumers were well aware of the importance of growth and vintage in determining the price of a wine. In the early 1830s a first growth—a wine from one of the region’s best vineyards—could fetch 3,000 francs per tun in a good year, fourteen times more than a Côtes or Palus wine did after a poor harvest (table 5.3). However, in the early 1830s many of the lesser growths after a good harvest actually sold for a higher price than wines from a top château after a poor one. Other French and foreign wines were also sold in Bordeaux, usually for blending purposes. This large range of wines made it crucial that they were adequately classified and that accurate information concerning their quality was provided to potential purchasers. By the late eighteenth century the use of both the grower’s and the shipper’s name (brand) was becoming frequent with fine clarets in the important British market, although the addition of the vintage was still rare.13

The many different wines produced and sold in the region led to the appearance of informal classifications for those involved in the trade from an early date. A hierarchy of regions, such as that shown in table 5.3, was the first step, which included both the quality of the vintage and the region of production (Médoc, Graves, Saucere). Subdivisions included the important wine-producing villages (St. Emilion, St. Julien). Finally, fine wines were identified by growths (first, second), and the best by their name (Château Haut-Brion).

TABLE 5.3

Prices and Output of Different Bordeaux Wines in the Early 1830s

In 1816 André Jullien published the first classification of Bordeaux’s leading vineyards in his Topographie de tous les vignobles connus, which listed five distinctive classes, although specific properties were found in only the first two.14 Other lists soon followed, published in both French and English.15 However, it was the Bordeaux classification of 1855, compiled by wine brokers (courtiers) for the Universal Exhibition of that year, that became and remains the reference for the wine trade and consumers alike.16 This listed fifty-seven red wine producers in five different growths and twenty-two white wine producers in a further three. All the red producers, with the exception of Château Haut-Brion (Graves), were found in the Médoc. The success over time of this classification was due to three factors. First, rather than a subjective study based on taste, it used prices that had been paid for different wines over many years. Second, it was compiled by the relatively impartial brokers, not the growers themselves. Finally, wine merchants considered it as only a rough guide and were quite willing to pay higher or lower prices when they thought a wine warranted it. This was important because the quality of a château’s wine varied not only according to vintage and growth, but also over time on account of changes in the level of investment and the quality of management.17 The 1855 classification became widely known in the second half of the nineteenth century, but consumers still often lacked good information on the quality of the different vintages, or how individual wines would develop over time.

The 1855 classification, however, ignored the great majority of vineyards in the region. As these included many good wines, the increasing popularity of claret encouraged growers to establish their own brands by adopting impressive names for their vineyards. The leading wine guide of the region, Charles Cocks and Édouard Féret’s Bordeaux et ses vins, listed 318 properties with the label “château” in its 1868 edition, but this increased to 800 in 1881, and 1,600 by 1900.18 Previously obscure vineyards, which may have produced excellent wines to sell under a shipper’s name, now gained a distinctive identity for themselves.

Having established a recognizable brand name, growers had to protect it. To avoid merchants mixing their wines with others, estate bottling was introduced, and with it the use of distinctive labels and branded corks. A leading shipper, Finke, noted for the 1868 vintage: “from several of our purchasers, namely Latour, Lafite and Larose, we obtained the right to keep and bottle the wines at their respective Châteaux, and it is our intention for the future to give as much extension as possible to this feature, as owing to the increased trade in Bordeaux wines, there is a greater demand for pure growths under their proper name, instead of, as formerly, for so-called 1st, 2nd, 3rd classes.”19

Only those wines considered of sufficient quality were bottled in this way. The high prices paid after a good vintage easily compensated for the lower prices received for poor ones, and, at least in theory, wines from poor vintages were sold as vin ordinaire rather than estate-bottled wines.20 The growing reputation of the leading châteaux also encouraged some of their owners to purchase other vineyards and to sell the poorer-quality wines using the estate’s brand name, but labeled as “second wine.” British wholesale merchants, however, criticized the trend of château bottling, claiming it was “a guarantee of origin, not of quality,”21 and feared that its widespread use would give producers considerably greater control of the market and a greater share of the profits, as was happening with champagne.

By contrast, for the cheaper Bordeaux wines, merchants were faced with having to purchase large quantities of very different wines from a considerable number of growers, and these required blending to achieve a product of consistent quality and stable price regardless of the nature of the local harvest. The Bordeaux wine trade would appear to have been in a position to establish and maintain the reputation of their wines better than most other regions. The 1855 classification of the leading growers provided a sufficiently accurate guide for fine wines, and by 1873 the well-established export houses were able to draw on the produce of a large and highly diverse wine district, reaching almost 200,000 hectares for cheap wines.22 However, exports for both fine and ordinary clarets peaked in the early 1880s, and producers faced serious economic problems by the turn of the century, although for very different reasons. Consequently we need to look at both segments of the market, starting with fine wines.

SUPPLY VOLATILITY, VINE DISEASE, AND THE DECLINE IN REPUTATION OF FINE CLARET

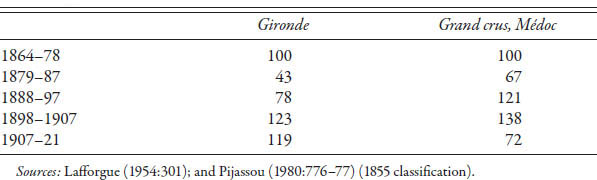

Phylloxera was officially noted in the Gironde in 1869, reaching the high-quality wine region of the Médoc in 1875. Its subsequent spread was much slower than in areas such as the Midi, as growers were worried that the new American vines would ruin wine quality and therefore spent heavily on chemicals to protect the traditional French stock. The négociants were just as skeptical of the new vines as the vineyard owners. One of the clauses of the 1906–10 abonnement (see below) that négociants agreed upon with Château Latour was that “the vineyard can in no way be increased during the period of the contract, and grafted American vines must be excluded, save those that are already there.”23

From 1879 a number of the smaller growers started injecting carbon disulfide around the vines. Growers with less than 5 hectares could request state aid at the rate of 25 francs a hectare, although this represented only about half the cost of chemicals required. By the mid-1880s there were eighty-eight local syndicates of growers established to protect vines in the Gironde, and they treated almost 3,838 hectares.24 Another strategy was the spraying of vines with sulfocarbonates, but because this required expensive pumping equipment, it was limited to the major growers, while other large producers installed pumps to flood their vineyards. The massive use of chemicals, the need for new equipment, and the heavy labor requirements made all these measures very expensive. As table 5.4 suggests, the high value of many of the Bordeaux vineyards led to a much higher percentage of the land being treated than elsewhere in France.25 The fight against phylloxera increased demand for labor, and this, together with the clearing of old vineyards and their replanting with the new American ones in areas of cheap wines, created much-needed employment for smaller growers whose own harvests were reduced by disease.

This heavy expenditure was successful in delaying phylloxera until growers and négociants were convinced that the new vines would not produce inferior wine. According to the historian René Pijassou, wine from the leading Médoc growers was still being produced from the old French vines until about 1900, and only after 1920 did it come predominantly from the new grafted ones.26 Therefore the large Bordeaux growers did not help small growers by experimenting with the new American vines to the same extent as large growers had done in the Midi or would do in Champagne. Pijassou has also argued that the string of poor harvests between 1882 and 1892, and the decline in popularity of fine clarets, cannot be attributed to phylloxera itself. Strictly speaking this was true, but the successful attempts to delay phylloxera by using chemicals resulted in an increase in the quantity of manure also being used. Traditionally vines had been manured once every twenty years in the Médoc, with Château Latour using 200–250 m3 each year before 1880. By 1884, after new antiphylloxera methods had been introduced, the quantities had multiplied five or six times because of the weakened vines,27 increasing yields on the leading Médoc estates and reducing the wine’s quality.

TABLE 5.4

The Response to Vine Disease in the Gironde, 1882, 1894, and 1905

Today scientific advances in vineyards and wineries have significantly reduced the number of poor vintages, and good-quality wine is produced in most years. In the nineteenth century quality was much more varied, and in the first two-thirds of the century, except for the years 1808–10 and 1835–39, there was at least one good harvest every three years, and each decade, with the exception of 1820s, enjoyed a minimum of four good harvests.28 The difference in the quality of the harvests was reflected in the price of the wine, with the price of Château Latour in the 1860s, for example, fluctuating from a minimum of 550 to a maximum of 6,250 francs a tun. For producers of fine wines, good years were those of high grape quality, and these were expected to be dispersed fairly equally over time. By contrast, the size of the harvest was much less important in determining revenue.

This pattern was interrupted by downy mildew, a disease that reduced the wine’s alcoholic strength and its keeping quality and devastated five consecutive harvests between 1882 and 1886. Between 1877 and 1893 no harvests were considered excellent, and six of the crops gathered between 1879 and 1886 were classified as poor, one as average, and just one as good.29 Even worse for the trade, the poor keeping quality of these wines was not at first appreciated, and wines believed to be good were bottled and sold by reputable merchants.30

The most famous case was that of Château Lafite, which after the harvest of 1884 sold its wine for £14 per hogshead, with “the right to bottle at the Château with the brand and label.”31 Several years later, when part of the consignment had been already sold by the shipper, it was discovered that the wine had turned bad. The legal dispute over who was responsible, together with the bad publicity that it generated, resulted in estate bottling losing its popularity among wine producers until the 1920s.32 The high prices paid for fine clarets depended on reputation, and Ridley’s noted a decade later that confidence had still not been restored:

In the ordinary course of event it might have been expected that the vintage of 1887 to 1893 would repair the damaged caused by those of 1882 to 1886, but this is evidently not the case, and Médoc Wines are still suffering from the discredit which the mildewed years brought them. As with Sherry, we here find how difficult it is to restore to popular favour an article upon which a stigma has once been placed.33

TABLE 5.5

Wine Output in the Médoc and the Gironde

The considerable drop in revenue caused by downy mildew occurred just as phylloxera was driving up costs, which encouraged growers to increase output, a trend that had already begun because of the heavy use of fertilizers. As table 5.5 shows, not only did the fine wine producers in the Médoc suffer less than other growers in the Gironde in the period 1879–87, but output in 1888–97 had more than recovered to the 1864–78 level. Château Latour, for example, increased output by 252 percent, but prices fell by 58 percent between 1879–87 and 1898–1907, while Château Margaux’s output increased from 450 hogsheads of supposedly “premier wine” to 1,200–1,400 hogsheads in 1903 of “indifferent” or “bad” wine.34 The leading négociants also suffered because although some had large stocks of vintage wines maturing in their cellars, most of their costs were fixed, and the decline in wine prices implied that their production costs rose from the equivalent of about 14 percent of the price of wine between 1875 and 1885 to 24 percent by 1905.35

The very success of names such as Château Lafite, Château Margaux, and others associated with the 1855 classification now contributed to this decline, as less reputable merchants in both Bordeaux and Britain exploited these brands by selling the large quantities of wines from the poor vintages that the desperate growers had in stock. Thus Ridley’s argued that

The Public, who unfortunately know more about Growths, than Vintages, receive Circulars offering Château this or Château that at apparently low rates, and on the strength of the name, purchase Wines which can but prove intensely disappointing. They then are apt to argue that, if Wines bearing the names of the best Estates of the Médoc be so inferior, those of lower grades must be bad indeed. Thus their faith in Claret, instead of in the Merchant who has sold it them, is shaken, and an inducement is at hand to try Wine from some other district.36

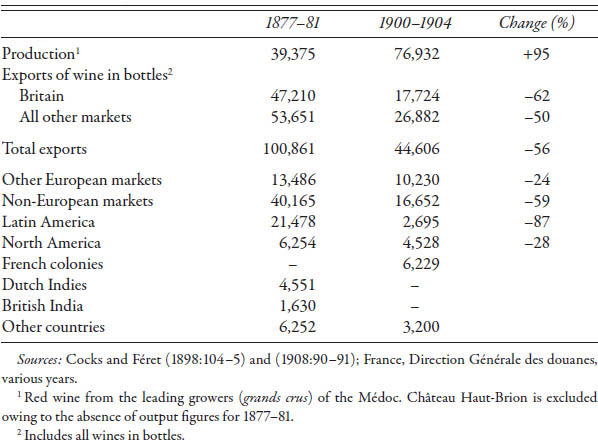

Exports of bottled claret to Britain, by far the leading market, slumped from 58,030 hectoliters in 1880 to 7,165 hectoliters in 1913. This was often explained by the growing popularity of smoking and drinking coffee instead of fine claret after dinner, the absence of good vintages from the early 1880s, and the decline in the reputation of the leading brands.37 In fact between 1899 and 1914 there were three excellent vintages, seven good ones, three average, and only three poor.38 Quality wines were being produced again, but the merchants had difficulties convincing skeptical consumers. The problems of declining reputation, together with rising tariffs, led to consumption slumping everywhere, with sales of bottled claret to Sweden falling by 86 percent, to Germany by 43 percent, to the Netherlands by 42 percent, and to North America by 26 percent, with only Belgium seeing an increase, by 38 percent.39 As a result, the British market for bottled claret in 1900–1904 was still larger than the rest of Europe and North America combined (table 5.6). The decline in sales to Latin America can be attributed to a combination of growing national production and rising tariffs.40 Tariffs were obviously not a factor in France’s colonial markets, and by 1900–1904 Senegal had established itself as the third largest market for bottled claret, after Britain and the United States.41

Table 5.6 shows that while the leading growers almost doubled output in the five-year period from immediately before the outbreak of downy mildew and to the turn of the twentieth century, exports of bottled wines more than halved. The economic depression for the leading Médoc growers was both long and deep. Many were forced to sell their properties, and land prices in the Médoc fell by up to 80 percent in the thirty or forty years prior to the First World War.42 Thus Château Malescot-Saint Exupéry (a third growth) was sold in April 1901 for 155,000 francs instead of the 1,076,000 francs it had reached in 1869, and Château Monrose (a second growth) was sold for 800,000 francs in 1896, down from 1.5 million francs in 1889.43 If the plight of Bordeaux’s leading growers in the early 1900s was as desperate as that in the Midi, the nature of the problem, and consequently its solution, was very different. In particular, the Midi’s growers and merchants competed on price and not quality, and the homogenous nature of their wines encouraged a group response. By contrast, the fine wine producers in Bordeaux needed to restore their own personal reputation for quality, and this could only be achieved if they limited output once more and invested heavily in their vineyards. Virtually all growers lacked both the capital and the means to improve their wines and change the negative perception of them in the market. The shift in market power to the producers during the quarter century or so following the 1855 classification and the introduction of estate bottling was now rapidly reversed, and the Bordeaux merchants once more dominated the commodity chain. In 1906 and 1907 a number of merchants entered into agreements (abonnements) with more than sixty growers, including half of the classed growths, to buy all their production at fixed prices over the following five or more harvests. Clauses were inserted in the contracts to limit output in an attempt to improve quality.44 Backward integration also took place, with a number of the leading properties being bought by merchants or their families.

TABLE 5.6

Production and Exports of Fine Bordeaux Wine (hectoliters)

However, the decline of claret sales required more than just uncoordinated, individual actions to improve wine quality. In 1909 a proposed “Trust” between growers and merchants to raise money to promote Bordeaux’s wines was debated but came to nothing, although the much more modest Fête des vendanges, which helped promote the Bordeaux “marquee,” was established.45 The British wine trade journal Ridley’s criticized the Bordeaux merchants’ marketing efforts:

The competition of Australian and Wines other than those of Bordeaux, and even more that of Whiskey, has undoubtedly diverted the public taste from Claret, but perhaps the most vital reason of all is a change in fashion. . . . It is, we believe, in a large measure because the Bordeaux trade do so little to attract the attention of the Public. . . . Think of the huge amount of money that has been spent on advertising Whisky, but no one would suggest that a similar amount should be spent on advertising Wine, the natural production of which is limited. Whisky did not appear to either the palates or inclinations of the Public at first, and it was nothing but the continual and also judicious advertising that has brought it into such World-wide repute. Similarly, on a smaller scale, with Australian Wines. Where would they be to-day, we would ask, had it not been for advertising? On the other hand, during the time those concerned in the sale of Whisky, Champagne and Australian Wines have been embarking on so vigorous a crusade of advertising, the Claret folk have done practically nothing, and unless they wake up and take steps by way of an outside appeal to the Public, they will incur the danger of getting still further behind. They have an object lesson before them in the case of Sherry, which from 1873 went continuously down, until the Jerez Shipping and their Agents woke up to the conclusion that something must be done, and this “something” was the formation of the Sherry Shippers Association, and the expenditure of a moderate amount of money on advertising. By this means they have not only stayed the decline, but turned the corner, and their Wines are slowly gaining in the estimation of the Public.46

RESPONSE TO OVERPRODUCTION: A REGIONAL APPELLATION

On the eve of phylloxera’s appearance, the port of Bordeaux was also France’s leading export center for cheap commodity wines, and a significant part of the growth in British imports came from here. Phylloxera caused a shortage of local wines, and French wine prices increased from twenty-five to forty francs per hectoliter between 1874–78 and 1880–84, despite imports increasing from the equivalent of less than 1 percent of production in the early 1870s to a third in the 1880s. In 1891 French wine production was 30 million hectoliters, imports 12 million, and exports just 2 million.47 By the mid-1880s Bordeaux was itself importing more wine that it was exporting, leading the British consul to note that “it is probable that about 50 per cent of all wines shipped from here last year to British ports in wood were ‘vins de cargaison,’ ” namely, local wines mixed with imported ones.48 The British press presented an even more dramatic story. Thus in the Telegraph we read: “An immense proportion of the wine sold in England as Claret has nothing to do with the banks of the Garonne, save that harsh heavy vintages have been brought from Spain and Italy, dried currants from Greece, there to be manipulated and re-shipped to England and the rest of the World as Lafite, Larose, St. Julien and St. Estephe.”49

Although it seems unlikely that wines of the 1855 classification actually suffered this fate, the frequent newspaper references to the supposed mixing with foreign wines and adulterations undermined claret’s reputation. Even after the French wine market switched from one of shortage to overproduction in the early twentieth century, British imports continued to fall, with competition now from the so-called basis wines, concoctions manufactured in Britain from imported grape juice and other substances and then mixed with French wines. According to Ridley’s, “people drink so called ‘Claret,’ composed of one-third of the genuine article and two-thirds of the British imposition, and condemn, not the latter, but Claret.”50

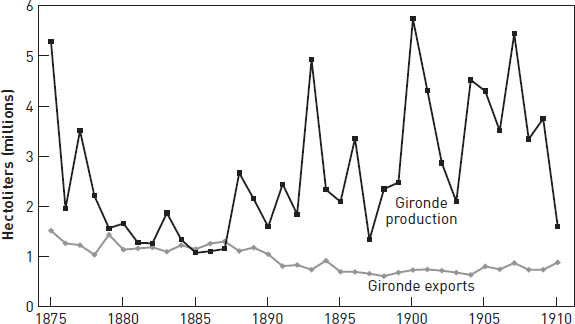

Bordeaux’s merchants argued that the high price and poor quality of local wines in the 1880s and 1890s required them to look elsewhere for supplies for blending. Nevertheless, this was not how local growers viewed the problem, especially as many were suffering from the heavy costs associated with replanting their vines after phylloxera and treating other vine diseases. As domestic harvests began to recover after phylloxera, pressure from the growers resulted in an increase in French import duties from two to seven francs per hectoliter in 1892. To protect the part of Bordeaux’s trade based on cheap vins de cargaison, merchants were allowed to import foreign wines duty free for the sole purpose of mixing with local ones for export.51 However, not only did Bordeaux’s export of these wines amount to little more than 200,000 hectoliters a year, but they were often sold in countries that were also major markets for fine wines, once more increasing the bad publicity.52 The free port was closed in 1899 and this, together with the growth of Cette as a distribution center for Midi and Algerian wines, and Hamburg’s highly competitive free port, contributed to Bordeaux’s decline as the international center for cheap commodity wines.53 As figure 5.3 suggests, exports drifted downward from the late 1880s, just when the Gironde’s wine production was recovering.

Figure 5.3. The Gironde’s wine production and exports, 1875–1910. Sources: Laf- forgue (1954:301) and Direction Générale des douanes. Tableau Général du Commerce de la France

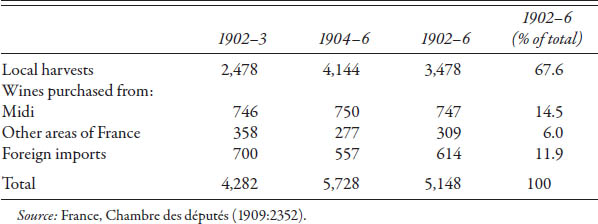

By the late nineteenth century Bordeaux’s growers (who numbered almost half as many as those in the Midi) were also losing their competitive edge in the domestic market for ordinary beverage wines, as lower rail freight rates made those from the Midi cheaper, not just in Paris, but also in Bordeaux itself. By the 1900s yields in the Midi exceeded those in the Gironde by more than 70 percent, and production costs were considerably lower. The 1907 parliamentary commission, which was chaired by Cazeaux-Cazalet, a deputy from the Gironde, noted that the wine crisis in the Gironde was caused by low-cost competitors (fraude par substitution) rather than overproduction (fraude par multiplication).54 The Midi sold in Bordeaux the equivalent of 28 and 32 percent of the Gironde’s harvest in 1902 and 1903, respectively, and wines from elsewhere accounted for a further 36 and 52 percent. However, when the average for the longer period between 1902 and 1906 is taken, the figures fall to 22 and 27 percent, respectively, implying that two-thirds of all the wines sold in the Gironde were still produced locally (table 5.7). Yet the Gironde’s growers were correct to identify the threat posed by the Midi. Local harvests in 1902 and 1903 were just 82 and 60 percent of the average between 1902 and 1906, while French wine prices were 5 and 47 percent higher. The Midi merchants sold less wine in the Gironde in 1904, 1905, and 1906 only because prices in those years were too low. Therefore, by the turn of the twentieth century competition from the Midi had effectively placed a price ceiling on Bordeaux’s vin ordinaire, and the region’s higher production costs made cultivation unprofitable in many years. Rather than exit the industry, the Gironde’s growers looked to regulate the market by restricting the use of the “Bordeaux” brand to their own wines and excluding all competitors, regardless of the quality of their wines.

TABLE 5.7

Wine Supplies in the Gironde, 1902–6 (thousands of hectoliters)

The 1905 law provided the legal framework to establish a regional appellation. Local growers argued that their wines were better than those from the Midi and elsewhere and pointed out that consumers required more information and a guarantee of quality if they were to pay higher prices. The most vocal opposition to the idea of an appellation came from the merchants within Bordeaux itself. They were opposed because they believed it would be harder to maintain stable prices and quality after a poor local harvest, as they could no longer use wines from other regions for blending and still sell them as “Bordeaux.” Indeed, they argued that if they were not able to mix local wines with those from elsewhere, they might not even buy from local growers after poor harvests.55 Many of the wines from Entre-Deux-Mers, Palus, and Réole, it was argued, required blending with the stronger Roussillon and Dordogne wines if they were to be transported.56 The merchants also claimed that a regional appellation guaranteed a wine’s origin but not its quality. Another complaint was that the new appellation would increase merchants’ operating costs precisely at a time of low prices. Merchants who brought wines from outside the Gironde were now obliged to keep two sets of books, and the government took the opportunity to levy new taxes on the required labels that showed the origin of the wine (five francs per hundred bottles). There were also concerns about implementation. To reduce fraud, the law of June 1907 required growers to sell no more wine than what they declared they had produced. But according to the Syndicat du commerce en gros des vins et spiriteux de la Gironde, growers ex-aggerated the size of their harvests in 1907 and 1908, presumably to enable them to buy cheap, non-Bordeaux wines to blend with their own.57 Another fear for the merchants was that if the regional appellation were successful in raising local wine prices, growers would respond by increasing output through planting on less suitable soils and using high-yielding vines. Finally, merchants believed that foreign governments might be tempted to impose higher duties on a supposed “luxury” wine, as many were already doing with champagne.58

Fine wine producers also considered a regional appellation largely irrelevant, as their consumers were supposed to be both rich and well informed. Nevertheless the leading growers and their merchants signed a joint agreement in July 1908 to find a solution to the sale of fraudulent wines. Although merchants questioned the need for outside controls of their stocks, they agreed to support the measures so long as they were not “inconvenienced,” and providing the measures were accompanied by a strict monitoring of growers’ harvests. The Ligue des Viticulteurs, which represented Bordeaux’s small growers, strongly criticized this joint agreement, claiming that the 1905 and 1907 legislation required merchants to control their stocks rather than apply voluntary controls.59 These producers viewed the influx of cheap wines brought by the merchants as the major cause of low prices.

Contemporaries interpreted the creation of a geographic appellation in two different ways: either as giving local growers the privilege of using the Bordeaux name regardless of the quality of their wine, or as an attempt to maintain quality by excluding inferior wines from outside the region. Opposition to the regional appellation was especially strong outside the Gironde itself, and growers and merchants claimed that it was an attempt to restrict competitive markets and represented a return to the privileges of the ancien régime. According to one writer, “with this system France will no longer be a country of free trade, such as was achieved with the Revolution, but a cluster of provincial monopolies protected by excise officers. We shall return slowly to the Middle Ages.”60

Historically a number of different wines had been transported down the Garonne and Dordogne rivers in the old administrative area of Guyenne and sold in Bordeaux. In particular, the producers from Marmande (Lot-et-Garonne) and Bergerac (Dordogne) argued that their wines were crucial for making up the wine deficit of the Gironde and contributed to the characteristic flavor of many of Bordeaux’s wines. The commission dismissed these arguments. In the first instance, the department’s archivist, Brutails, provided historical evidence that the time of year when wines from outside Bordeaux could be sold was strictly controlled prior to the French Revolution, and that they were required to be sold in different-sized casks from those of the Bordelais.61 This suggests that these wines had not been considered crucial for blending with those from Bordeaux for the export market. Furthermore, Brutails noted that numerous nineteenth century authors, including Édouard Féret, had clearly identified Bordeaux wines with the Gironde, rather than with these other regions of the old province of Guyenne.

Statistical evidence suggests that whatever the importance of these regions in the past in supplying Bordeaux with wines, it had declined significantly by the early twentieth century. The Gironde’s average harvest between 1902 and 1906 was 3.5 million hectoliters, and it exported and sold to other regions in France a total of 4.3 million. Of the balance, together with wine used for local consumption (1.7 million hectoliters), just 11 percent came from Lot-et-Garonne, Lot, and the Dordogne, compared with the 37 percent imported from other countries (including Algeria), and 45 percent from the Midi (table 5.7). The commission in charge of establishing the appellation concluded that the neighboring departments provided “relatively negligible” quantities of wine, and therefore they were unlikely to be important for blending with Bordeaux’s wines.62 Yet for many of Bordeaux’s growers of ordinary wines, the regional appellation was a cheap and easy way to restrict competition from growers in the Midi and elsewhere who enjoyed lower production and marketing costs. As a measure for guaranteeing quality, however, consumers would have to wait until after the Second World War, when the appellations contrôlées included restrictions on grape varieties and production methods that could be used.63

In retrospect, Gladstone’s attempt to allow British consumers to drink cheap claret was badly timed, as shortages in France soon drove up prices. In their attempt to sell large quantities of cheap commodity wines through the new commercial outlets in Britain after 1860, merchants found it difficult to maintain the reputation of claret because of the absence of an easily defined product, or the security that wines would not be adulterated after leaving their cellars. When these problems coincided with a shortage and high price of wines because of disease in the late nineteenth century, even the traditional marketing arrangements based on the individual reputation of Bordeaux’s négociants and the local retail wine merchant were threatened. Once reputation had been lost, growers and merchants found it very difficult to restore consumer confidence even when quality improved later. As Penning-Rowsell noted, the failure by the wine trade to recognize initially the quality of the 1906 vintage exemplifies the state of the market at this time, as it was later considered the best between 1900 and 1920.64

1 Trade was especially strong after the French recaptured La Rochelle in 1224 (Penning-Rowsell 1973:80–81).

2 Hume (1752:88).

3 Robinson (2006:90).

4 Roudié (1994:69–71).

5 Ridley’s, June 1907, p. 445.

6 Lafforgue (1954:293); Cocks and Féret (1908:6).

7 Féret (1874–89:461) gives a salary of 225 francs, while Bowring suggests 150 francs. The operations included pruning, collection of cuttings, putting down vine props and laths, fastening the vines, and twice drawing the cavaillons (United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers 1835:150).

8 Higounet (1993:101). By contrast, on the eve of the Second World War there were reports concerning the work quality of the prix-faiteurs (France, Ministère de l’Agriculture 1937:163).

9 Jouannet (1839:229–30) suggests that the joalles were found on the hills, but Cocks and Féret (1883:52) also give the Palus.

10 Revue Agricole, Viticole et Horticole Illustrée, May 15, 1906, pp. 154–55.

11 Jullien (1826), cited in Penning-Rowsell (1973:156). Henderson (1824:183) appears to cite earlier editions of Jullien. Cavoleau (1827:128) speaks of the premier crus of the Médoc being mixed in this form to produce an inferior article, but one that met consumer demand.

12 Jullien (1824:113).

13 In 1797 Christie’s sold “vintage” claret—six hogsheads of ‘first-growth claret’ from 1791 (Penning-Rowsell 1973:109).

14 Jullien (1816). Some of the courtiers had their own private lists in the eighteenth century. See Markham (1998) for a history of the classification of Bordeaux wines.

15 For example, in French, Franck, Traité sur les vins; Le guide (1825); Paguierre, Classification (1829); Cocks, Bordeaux (1850); and in English, Jullien, The Topography (1824); Henderson, History (1824); Paguierre, Classification (1828); Redding, History and Description (1833); and Cocks, Bordeaux (1846).

16 The 1855 classification was the response of the Bordeaux Commodities Market to a request from the local chamber of commerce. It took only two weeks to compile, although, as noted above, there was a tradition of classifying the estates. It was not supposed to be a definitive guide (and there would have been bitter fighting among interest groups if they thought this was going to be the case), but, with just two exceptions—in particular the promotion of Château Mouton-Rothschild to a first growth in 1973—the list has remained unaltered to this day. Brokers provided exporters with the knowledge of where suitable wines could be bought and their price.

17 Only Châteaux Mouton-Rothschild and Léoville-Barton have remained with the same family since 1855 (Robinson 2006:175).

18 See Roudié (1994:142).

19 Ridley’s, March 1869, p. 5.

20 “It is said that £37 has been offered for the Mouton Rothschild 1887, with the right to have it bottled at the Château; but the proprietor is reported to have refused to allow the bottling clause” (Ridley’s, April 1888, p. 164).

21 Army & Navy Co-operative Society, cited in Ridley’s, June 12, 1889, p. 298.

22 This was significantly more than it had been earlier in the century. Franck in 1824, for example, gives only 130,000 hectares. Traité sur les vins, cited in Roudié (1994:31).

23 Higounet (1993:276–77).

24 Government aid was 95,967 francs in total. The eighty-eight syndicats had 2,535 members with 5,652 hectares of vines in total. In Libourne there were forty-six syndicats, 1,565 members, and 3,830 hectares, compared with Lesparre (representing most of the Médoc), which had only thirty-nine members and 145 hectares (Feuille vinicole, September 15, 1887).

25 This was also true within the Gironde itself—for example, in 1898 the villages of Cussac, Cantenac, Margaux, St. Estèphe, and St. Julien, which accounted for 2.5 percent of the vines but 4 percent of the area flooded, 37 percent of the vines treated with sulfocarbonates, and 12 percent of those treated with carbon disulfide (Arch. Gironde 7 M 219).

26 Pijassou (1980:763).

27 Ibid., 779–80.

28 Petit-Lafitte (1868, table C). In 1820–29 there were only three good harvests. The 1811 vintage was considered exceptional.

29 Cocks (1969:137). The measure of wine quality is not an exact science, especially as an initial judgment of a wine’s quality can change by the time it is drunk. Lafforgue (1954:299) provides slightly different results.

30 In 1891 it was noted that the “instances in which Wines had gone wrong after being put into bottle were by no means few and far between, and the trouble caused both to shipper and importer became at one time a very serious matter. Of late, however, complaints have been far less frequent” (Ridley’s, January 1891, p. 5).

31 Ibid., January 1887, p. 35.

32 According to Nicholas Faith (1978:96), poor-quality wines, together with the increase in duty on bottled wine in Britain after 1888, “set back the cause of bottling near or at the grower’s for a generation.” See also Feuille vinicole, January 27, 1887.

33 Ridley’s, July 1894, p. 400.

34 Higounet (1993:297); Ridley’s, April 1903, p. 675.

35 Béchade (1910:102).

36 Ridley’s, September 1897, p. 576.

37 “English habits . . . have undergone a considerable change during the past 30 years, and the after-dinner half-hour is now monopolized by coffee and tobacco, while Britons have not yet accustomed themselves to serve fine claret or burgundy with roast meat or game” (letter by Gilbey to The Times, September 29, 1896).

38 Cocks (1969:137).

39 I include those years when no figures are given (Germany 1881; Canada 1880, 1901, 1902; Sweden 1904), even though some exports are probably included in “all other countries” for these years. By excluding these years, the decline in imports is in Germany –55 percent; in North America, –23 percent; and in Sweden, –82 percent.

40 Salavert (1912:187–88). For tariffs, Cocks and Féret (1908:1051–64).

41 Export to Senegal averaged 3.7 million hectoliters in 1900–1904, against 17.7 million to Britain and 4.1 million to the United States.

42 France, Ministère de l’Agriculture (1937:159).

43 Land prices fell in the thirty to forty years prior to 1914 by 80 percent (Pijassou 1980:815–16). Farm wages doubled in the Gironde between 1826 and 1870, but from this date until the First World War wages in the Médoc increased from 2.75 to 3 francs, considerably less than the national average (France, Ministère de l’Agriculture 1937:173, 459).

44 Cocks and Féret (1908:xvii–xxii); Higounet (1974:335). The négociants insisted for Château Latour that “the vineyard can in no way be increased during the period of the contract, and grafted American vines must be excluded, save those that are already there” (Higounet 1874:276–77).

45 Roudié (1994:227–29).

46 Ridley’s, January 8, 1914, p. 5.

47 Annuaire statistique (1938:63, 179–80).

48 British Parliamentary Papers, Consular Report, Bordeaux, 1889, no. 501, p. 9. For trade, see Roudié (1994:180).

49 Ridley’s, July 1887, p. 315.

50 Ibid., April 1906, p. 338.

51 Roudié (1994:212–13); Gallinato-Contino (2001:171–82).

52 Audebert (1916:15), in Arch. Gironde, 8 M 13.

53 Farou, La Crise Viticole et le Commerce d’Exportation (1909), in Arch. Gironde, 7 M 169, 7–12. Phylloxera in Catalonia and Navarra also created difficulties in obtaining wines from Spain. By contrast, Hamburg merchants bought wines from the cheapest producers, whether in Portugal, Greece, Turkey, or Hungary, were more efficient at creating wines, and even enjoyed lower freight rates to Buenos Aires than did Bordeaux.

54 Revue Agricole, Viticole et Horticole Illustrée, June 15, 1907, no. 183.

55 Feuille Vinicole, May 12, 1910.

56 Vitu (1912:70).

57 Arch. Gironde, 7 M 190.

58 Feuille Vinicole, May 12, 1910.

59 Arch. Gironde, 7 M 169.

60 Cited in Vitu (1912:55–56).

61 Brutails (1909), in Arch. Gironde 7 M 187.

62 Cazeux-Cazalet (1909:4–10), in Arch. Gironde 7 M 187.

63 Cooperative wineries in the region did not appear until the 1930s, in part because the growers cultivated a greater variety of grapes, which presented difficulties in measuring wine quality.

64 Cited in Higounet (1993:330).