Chapter 7. Conclusion: Toward a New Model for Innovation

"Innovate or die."

—Various

In the wake of the technology boom and bust, the "anything goes" approach to innovation quickly became a tired fad. Successive waves of previously celebrated and much-emulated innovators, both big and small, had stumbled or even failed. Innovation buzzwords formerly spoken with rapt enthusiasm became the subject of deprecating sarcasm. Vague novelty now was severely discounted, not generously rewarded. The deflation of each successive innovation fad and fashion brought disappointment and disillusionment.

Many companies decided to literally cut their losses by shuttering their corporate ventures and VC funds, writing (and shutting) down their acquisitions, ending their alliances, and unwinding their spinouts. They retreated inward, defensively retrenching and refocusing. Much of this introspection was a necessary respite, of course; it gave them a chance to try to regroup and recover from the binge. The overly urgent innovation call-to-arms had quieted, making way for more sober reflection and reconsideration. What, if anything, did we learn?

Despite the myriad missteps and malfunctions, no one seriously doubted that innovation would continue to be a more important and pressing challenge than ever. The New Economy pressures that had driven so many companies to experiment so eagerly had not suddenly disappeared. Although none of the newfangled approaches toward innovation appeared to have worked consistently well in practice, the vast majority of executives and entrepreneurs alike also sensed that a return to the old ways was not a promising, workable answer.

The traditional model for innovation truly was passé. Times had changed. The purveyors of the various "innovation in innovations" were mostly correct in this regard: The old model of innovation no longer worked. In terms of both content (generating new ideas, technologies, and businesses) and structure (the organization necessary to successfully execute these ideas), it fell short. No longer could companies depend entirely on their own "nose-to-the-grindstone" R&D labs and their established internal organizational structures and processes. They no longer were doing the job. An alternative still was sorely needed. This, after all, was precisely why companies big and small had so enthusiastically chased after each successive innovation fad and fashion as it had emerged. The question was: Where do we go from here?

Amidst all the wreckage and reassessment, a new model for profitable and sustainable innovation began to more clearly emerge. By grappling with their own particular post-bubble challenges, many companies began the process of discovering and implementing, shaping and refining, this new approach. Few explicitly articulated the new design, however. This is one of our key objectives in concluding our broad-ranging discussion of various innovations in innovation.

Core Complexity

The emerging model for innovation is both simpler at its core, and yet overall considerably more complex than any of its predecessors. First, the new paradigm is simpler because of its renewed emphasis on the central, foundational importance of core innovation. There was a sense among many, if not agreement among all, that organizations should no longer bet their future on juggling dozens of diverse, peripheral, and experimental ventures in the hope that somehow, somewhere, one of these marginal "real options" would strike "in the money" big time. Instead, committed and integrated innovation with focus and fit is the real challenge, and the real source of rich rewards.

Overall, however, the emerging innovation paradigm is much more complex than the old traditional, inward-focused, internal R&D approach. It's also more complex than any single one of the largely transactional remedies promised by each of the individual innovation fads and fashions. In sum, the new model is more complex because it increasingly requires organizations to focus on generating and nourishing core innovation, even while simultaneously maintaining a more active balance of innovation sourcing and peripheral experimentation from both inside and outside. It therefore requires deft mastery of more numerous and varied sets of tools. These tools include, in their proper place and perspective, not just one, but all the innovation tactics we have discussed: venturing, licensing, alliances, acquisitions, and spinouts. The new model therefore is not a simple quick fix. Instead, it's a more complicated and dynamic mix. But it's a mix that also is more rational, effective, and sustainable.

Many of the old innovation skills and goals remain essential. Without a strong internal R&D culture and without home-grown innovation, for example, there is little grounding and coherent direction for a firm's overall innovation strategy. An innovation strategy with a strong internal core is the best source of a sustainable competitive advantage. Just as important, it's the base and leverage with which to effectively and profitably exploit even outsourced innovations in a superior fashion.

The new model for innovation requires more than a flourishing organic innovation culture, however. It also requires the complementary addition of more open elements of culture, new sets of skills, and different types of objectives. It requires a strategy and organization that can foster the power and pride of "Invented Here," even as it can rapidly identify and effectively assimilate Not Invented Here (NIH). This is a very different and challenging sort of balance, but it's far from an impossible task. This is, in fact, the new essence and the principal goal of the emerging model of innovation.

Lessons Learned: Rediscovering the Core

One key lesson learned from the aftermath of all the innovation fads and fashions was that core innovation must be the primary investment. What all the innovation fads and fashions had in common was that, in both presentation and execution, they tended to ignore, neglect, or distract (and therefore ultimately detract) from core innovation. They ventured further and further from the real strategies and real businesses that begged for innovation the most, the massive and looming problems and challenges that really needed novel ideas, new technologies, and fresh approaches. Disconnected from their companies' cores, little guide or grounding existed for these innovation experiments. There were few strategies, mostly just tactics; it was novelty for novelty's sake. As a result, many of these adventures were set up to fail from the beginning, not given a head-start boost as promised.

In contrast, at the center of the new model for innovation is a renewed appreciation for, and focus on, core innovation. Profitable and sustainable innovation is not about wanton novelty at the periphery. It's not about abandoning a firm's core R&D, organization, channels, and customers because they're just too "old" and "tired." In extreme but extraordinarily rare cases (such as the rapid, impending decline or destruction of an entire technology, company, or industry), abruptly abandoning the old might make sense. But this is extraordinarily uncommon, and even in these cases, it's rarely a completely sudden event with no opportunity to adjust. A firm's innovation core is still most often the guiding force by which to plan and execute such a transformation. Even with the need for radical change, transforming the old core—not completely abandoning it—usually is a superior value-creating bet, one with much better odds.

The CEO of bakery-café casual chain Au Bon Pain managed to pull off such a rare transformation when he jettisoned the flagging core brand, refocused on a newer and more upscale concept, and rebirthed the entire company as Panera Bread. Au Bon Pain had acquired the Panera Bread concept with its purchase of the small St. Louis Bread Co. chain. By 1999, Panera had grown to almost 200 stores. With slowing sales and operational difficulties at the core Au Bon Pain franchise, going forward, the new concept looked to be the more attractive option. The Au Bon Pain name and chain were sold off and Panera Bread was born.

Even in this very uncommon and relatively radical case, the successful innovation transformation was not a wholesale leap from the essence of the original business. The focus was still casual dining, centered around bread, baked goods, sandwiches, and coffee. Au Bon Pain initially used an acquisition to infuse new concepts to the chain. It developed and incubated them further internally over a period of five years. Only then did it use the entire initiative as a launch pad to vault to a new (although still closely related) innovation core. This transformation also was made much more plausible by the fact that it was a relatively small and simple company.

A related lesson from the innovation boom and bust is that the dire, urgent warnings about the need for rapid and radical innovation at all costs most often proved unwarranted. Despite all the breathless excitement about the need to innovate or die, the fact remains that most established businesses were not displaced and replaced by agile and tech-savvy upstarts. Established retailers and manufacturers, from financial service companies to health-care providers, were not upended and overtaken by technology. More often than not, in fact, the established leaders became the survivors or "thrivors." The success of innovative thrivors Dell, Wal-Mart, and Southwest Airlines long predated the technology bubble, for example, yet each company used the power of the Internet to leverage their core marketing and operational capabilities toward even greater industry domination. They used their existing core innovation as a base and as leverage with which to more quickly and fully exploit the potential of the Internet in order to enhance their already formidable advantages.

These are three of the most successful cases, but they're not entirely exceptional by any means. The fact remains that most successful, established companies proceeded to adopt and adapt major innovations, whether through organic development or external acquisition, throughout the technology ferment. It was never a completely smooth process, but neither was it an impossible struggle, contrary to much of the advice and many of the prescriptions at the time. Those established firms that failed or lagged tended to be slow casualties of longer-term trends, especially internal dysfunctions such as deteriorating core innovation. They rarely were blindsided victims of some sudden technological revolution.

The implication of these dynamics is that, for the vast majority of contexts and decisions, core innovation is what powers companies forward and, consequently, what must be their continued emphasis, even as the latest and greatest new ideas and technologies take flight. An established company cannot ignore its legacy and hope for innovation salvation from some wild and far-flung venturing experiment, an expensive hot bet on an early stage, R&D-driven, long-shot acquisition, or a clever but convoluted new-tech spinout. Even when such ventures are successful in their own right, decay at the core might continue or even accelerate. Even successful off-line experiments rarely are sufficient to offset the loss of the chance for renewal in a firm's core, and the consequent likely destruction of enormous amounts of value.

Using New Tools to Power the Core

To power the core, all the new approaches to innovation we have explored in the previous chapters are increasingly critical for innovation success. They work best to infuse, not replace, the core. To this end, what has powerfully propelled most of the successful innovators forward through the innovation boom and bust and beyond has not been a return to their old ways. They have not retrenched to a single-minded focus on internal R&D and "sticking to their knitting." Nor have these companies jettisoned their core to aimlessly chase after some even more newfangled innovation experiment. In fact, in each case, refocusing on their cores has served as the fundamental guide and indispensable anchor for their renewed innovation strategies. With such strong grounding, they've then been able to successfully experiment—both inside and outside their organizations—to create, capture, and exploit the innovation they need, from whatever the source.

The examples range from formerly tarnished names such as McDonald's and Procter & Gamble, companies that stumbled but managed to regain much of their former glow, to younger brand-name exemplars such as Starbucks, companies that grew restless during innovation mania but that regained their focus. The examples also include entrepreneurial firms that are dominant in their own market space, firms like Replacements Limited and its transformation to Replacements.com.

In each of the earlier chapters, we dedicate considerable discussion to the innovation challenges of myriad cutting-edge, high-tech companies. The following examples take the cutting-edge technology down a level. However, the lessons about the importance of core innovation are just as applicable to hi-tech and low-tech companies alike.

Leveraging the Core: Little Things Mean a Lot

The simple and familiar example of McDonald's shows the profound importance, and the power and leverage, of core innovation. By 2002, McDonald's corporate venturing with its diverse Chipotle, Donatos, and Boston Market chains had contributed relatively little to its revenues and profits—in fact, mostly big losses—during the previous few years. Fast-food price wars involving the core McDonald's franchise also had taken their toll. Cheaper burgers were only fattening more and more waistlines, not the company's bottom line.

In December 2002, in the wake of several disappointing quarters, McDonald's CEO stepped down. A Wall Street Journal story summed up the stark situation that any new management team would confront: "McDonald's Corp. gave investors more heartburn, warning that the company expects to report its first quarterly loss since going public 37 years ago." McDonald's stock slid to a new multiyear low, slashing billions from its market capitalization. Retired former international chief Jim Cantalupo returned to McDonald's as the new CEO to tackle what undoubtedly would be a long and tough job ahead.

Only a year later, however, the headlines were far different and McDonald's stock surged. It posted record cash flow for 2003 and a big year-end boost in sales and profits. What radical shift helped produce such phenomenal results? A key part of the quick turnaround was simply the introduction of new core product offerings. Some products were more "radically" innovative than others, but together they all helped tip the company's momentum in the right direction. McGriddles, for example, upgraded and updated the venerable Egg McMuffin in a unique, convenient, and satisfying (if not all that healthy) sweet pancake-sandwiched breakfast meal. At the same time, the chain's healthier-option premium meal salads appealed to a different crowd, yet without the stigma of its earlier infamous offerings like the much maligned "seaweed" burger, the McLean Deluxe.

McDonald's new management team emphasized that igniting a turnaround involved more than McGriddles and salads. But both were critically symbolic of a larger refocusing on core innovation in McDonald's main lines of business. Both offerings promised fast, consistent, and satisfying food. They offered taste, convenience, and value. People who hadn't visited McDonald's in a while started to come back and visit more often.

Kids of all ages could indulge in new tastes like McGriddles, even while leaner white-meat McNuggets and healthier Happy Meals also appeared on the menu. Perhaps more importantly, customers who had abandoned McDonald's convenience and consistency in pursuit of lighter tastes now could grab a quick, quality meal salad. The healthier, updated salad offerings were a big hit among athletes at the Summer 2004 Athens Olympics, for example, a key part of McDonald's ongoing global marketing and sponsorship efforts. Consistent with these efforts, the company nixed its Super Size menu option as a matter of policy in mid 2004, just prior to the wide release of the obesity shock-umentary Super Size Me. With fortuitous timing, this stream of seemingly small but collectively significant shifts helped blunt an imminent tobacco-style attack on fast food that was clearly targeted at McDonald's.

Even so, McDonald's did not abandon its classic burgers and fries by any means. Instead, it revamped and renewed its core mix of offerings to powerful effect. The average salad-buyer meal tab, for example, totaled nearly double that of the more typical burgers-and-fries crowd.

Protracted fast-food price wars were out; core innovation was back in. With more than 30,000 outlets worldwide and greater than $40 billion in annual system-wide revenues, McDonald's 10 percent year-over-year boost in fourth-quarter 2003 sales was not an insignificant event. Given the enormous leverage of McDonald's core business, little things clearly mean a lot.

At the same time, McDonald's announced the sale or closing of many of the experimental, non-core brands and joint ventures, including Donatos Pizza and Fazoli's. Just a couple years earlier, much of McDonald's hopes centered on the promise of new growth with these supposedly more updated and upscale concept ventures. In contrast to these drawn-out, cash-draining experiments, however, the sudden revival of McDonald's core business created enormous value in a relative flash. The stock more than doubled from its low.

Under the umbrella of McDonald's Ventures, however, the company did retain the Chipotle Mexican Grill chain and the U.S. Boston Market franchise. Few questioned the company's retaining these ventures, at least experimentally. Henceforth, they would be developed and funded largely of their own accord. With a new strategy, McDonald's put corporate venturing more in its proper place and perspective: as an experiment and as a learning tool, and possibly as a longer-term bet, but not to the neglect of core innovation. The company renewed its focus and righted the balance between core innovation and venturing.

Unfortunately, tragic events struck McDonald's in 2004. Yet even these terrible events helped further illustrate the durable and profitable power of core innovation. With his fresh new strategy still very much a work in progress, Jim Cantalupo suddenly died of a heart attack in April. Then, just two weeks later, Cantalupo's relatively youthful 43-year old successor, Charlie Bell, received grim news. Bell told the board and the world that he would be fighting a serious battle with cancer. In another short couple of weeks, Bell had surgery and began a rigorous round of chemotherapy.

Despite the tremendous challenges that these events presented in rapid-fire succession—the sort of turmoil that could easily send a company reeling—under Bell's leadership, McDonald's continued to power forward with its renewal. Second-quarter 2004 sales increased 10 percent, and profits leapt 25 percent. Margins grew to nearly 20 percent, the highest in a decade. Overall, for the first six months of 2004, net income was up 33 percent compared to the same year-earlier period.

McDonald's clearly still faced serious challenges, both in terms of continuing to refine and execute its new strategy and in terms of ongoing uncertainty about its leadership. With little doubt, however, these early results provided a substantial down payment on its renewed investments in core innovation—a performance all the more remarkable in the face of such sudden adversity and uncertainty.

Fueling the Core: Innovating Beyond the Obvious

Core innovation often goes far beyond tweaking existing products or even reinvigorating entire product categories. Sometimes, it doesn't involve the core product directly much at all. Nonetheless, the leveraged power of core innovation can take even relatively minor new ideas and technologies and turn them into substantial gains; little things mean a lot. This dynamic can be seen in a technology-related example from Starbucks that has little to do with coffee directly, but much to do with enhancing the delivery of "the coffee experience."

Starbucks was one of the more fantastic innovation success stories of the 1990s. Even as per-capita coffee consumption plummeted by 50 percent during the previous three decades, Starbucks launched and thrived. It offered the relatively unique experience of made-to-order, ready-to-drink, barista-manned espresso coffee outlets that were oddly positioned somewhere between a McDonald's and an authentic European café. It let customers buy into the espresso experience. It let them feel special to splurge on an affordable luxury and get their caffeine and sugar fixes at the same time. Having a slightly addictive product didn't hurt either.

Even Starbucks got distracted and caught up in Internet fever, however. During the height of froth over the web, company founder Howard Schultz uttered his instantly infamous line that Starbucks would henceforth be an Internet company. More than a few people were scratching their heads trying to figure out what that meant. In 1999, Schultz explained his goal of setting up a separate Internet venture division to push the Starbucks brand and experience into e-tailing and other forms of online communing and commerce. Most observers thought it was fortuitous that Starbucks never got very far with the idea before the bottom fell out of the dot-com craze. Starbucks quietly shelved the idea and refocused on delivering the coffee experience.

Starbucks did have a future in e-commerce, only of a different sort. In late 2001, the chain introduced the Starbucks Card, a stored-value payment card. What do coffee and stored-value cards have in common? On the surface, not much. But the cards made it easier, faster, and cheaper to get one's urgent caffeine fix at the corner Starbucks café. Customers could buy stored-value Starbucks Cards and then pay for their usual cup with a simple swipe. No fumbling for change, and the cards could easily be refreshed online at Starbucks's web site. Later, Starbucks co-branded credit cards were introduced, with rapidly earned rewards in the form of espressos and lattés.

Starbucks was a habit. The cards made the habit even more convenient to indulge. Same-store sales perked up significantly. Now Chairman Howard Schultz and CEO Orin Smith both noted that the Starbucks Cards were one of the most significant and successful Starbucks innovations since the Frappuccino was introduced with great success in the mid 1990s. Another core innovation, the Frappuccino initially garnered little enthusiasm among Starbucks leadership, but within a few years, it became a billion-dollar business in its own right.

A co-developed, stored-value payment card as a core innovation for a coffee chain? It's a gimmick that would not have worked nearly as well for most types of retailers or food-service establishments.

Few chains have so many locations and with such a loyal base of customers visiting so regularly and frequently. The cards made loyalists visit and buy all the more. It was a perfect fit for Starbucks that honed their focus on delivering "the coffee experience." Although Starbucks Cards were a seemingly tangential innovation to the company's main product and service offerings, they nonetheless significantly bolstered Starbucks's coffee business. They fueled the core.

Transforming the Core: Internalizing Radical Innovation

At very rare but critical times, the challenges of innovation justify (or even require) a more radical and transformative approach. The aforementioned case of Panera Bread is one such example. The rapid evolution of Replacements Limited to Replacements.com provides another good illustration of a radical core transformation, and of how it can strongly invigorate an already powerful business model.

Replacements Limited had been in business for 15 years before e-commerce really emerged as a channel. The company already had built a lucrative $50 million-plus annual business by making itself the leading, go-to source for replacement china, crystal, silverware, and similar housewares. Originally, it seemed a bit of a quirky business idea; that the concept raised some eyebrows when founder and CEO Bob Page first floated it. The idea was an outgrowth of his flea-market hobby, after all: collecting china and crystal, collectibles, and the like. Page was denied small-business loans by state officials who told him the strange concept "would never work."

Quirky or not, more than a few people were willing to pay for the value Replacements Limited provided. Customers could easily and quickly replace a lost or broken item in their heirloom or wedding set of china or crystal, for example, rather than having to buy a whole new set for thousands more. Relieved and gratified patrons were willing to pay good margins for such service and product. It was a fantastic win-win value proposition for both customers and Replacements Limited. Replacements so thoroughly dominated its market by the late 1990s that the next largest competitor was only about 1 percent its size. Replacements Limited had built a nationwide network of suppliers and had amassed an unrivaled inventory of millions of patterns and items.

With the advent of the Internet, however, e-commerce offered a host of challenges. The web directly presented technology and channel challenges for a firm that had been doing business primarily by phone and mail, with just one retail outlet for more than 15 years. The web also presented some unprecedented competition, especially one called eBay. Although it was not a direct competitor, eBay was probably the biggest threat that Replacements Limited had ever faced. Customers might simply tap into eBay's limitless virtual inventory of virtually everything and anything to try to find and acquire replacement items, and therefore bypass Replacements Limited altogether. By 1998, Replacements Limited had to decide whether to jump on board the dot-com bandwagon: Should it create a new Internet venture division, or should it form a new dot-com spinout as so many other companies were doing?

Replacements chose neither path. Instead, CEO Bob Page decided to transform the entire core of the enterprise. Replacements Limited began a methodical but rapid transition to become Replacements.com. They eschewed high-priced IT consultants who were hawking their latest-and-greatest, bells-and-whistles web technology. Instead, for a fraction of the price, Replacements developed and implemented its far-reaching adaptation to e-commerce primarily with its own in-house expertise, supplemented from outside as necessary. Its developers focused on quickly creating basic Internet functionality, including fast-to-load and easy-to-use web pages. The completed system gave customers access not only to full pricing and product information, but also offered transparent real-time access to Replacements's own inventory databases.

The process had its challenges. By committing wholesale to the initiative, however, Replacements's essential transformation was achieved in less than a year and for less than $1 million. Replacements Limited quickly and effectively transformed into Replacements.com, doing the majority of its business on the web. Within a few years, sales increased nearly 50 percent, even as its Internet adaptations significantly lowered both operating and marketing costs. Privately held Replacements.com not only survived the dot-com downturn, but positively thrived throughout the turmoil.

By 2002, Internet Retailer named Replacements.com a leader in e-commerce, along with other much larger colleagues, such as Amazon.com and eBay. For Replacements Limited, taking its old-fashioned business model and venturing online was not a peripheral experiment. Instead, Replacements Limited successfully identified and tackled the challenge as one requiring the methodical yet rapid transformation of the entire firm.

Core Innovation ≠ Internal R&D

It's critically important to note that, in emphasizing the centrality of core innovation as a fundamental guiding principle, we emphatically are not endorsing a nostalgic return to the old internal R&D myopia or a simple, inward-focused "stick to the knitting" approach. Internal R&D and new business development are vital, foundational ingredients in the innovation mix. However, core innovation can come from anywhere, from either inside or outside the organization. Keeping it all inside, organic R&D alone is not the answer, and it is certainly not our recommendation. The cases we discuss in each chapter illustrate this well:

-

RF Micro Devices (see Chapter 3) could not have long existed, much less flourished, without first striking a manufacturing alliance with, and then later in-licensing key technology from, TRW. Despite years of effort and development of their own technology and patent portfolio, RF Micro Devices's internal R&D was simply not sufficient to bring their innovation to fruition. TRW's gallium arsenide semiconductor technology was a critically necessary key to unlock RF Micro Devices's latent value, making the license worth even the rich price of one-third of the company. Later, as the wireless semiconductor industry continued to evolve, RF Micro Devices began to ink both R&D M&A deals and new R&D and manufacturing alliances to try to gain expertise and capabilities in silicon chips and chipsets, areas quite a bit beyond their core competencies in gallium arsenide, even as the company continued to invest more in its own internal R&D efforts. Almost from RF Micro Devices's inception, core innovation never implied simply toiling away at its own narrowly focused internal R&D.

-

Biopharmaceutical startup Trimeris (see Chapter 4) needed more than just the cash and marketing resources that a licensing deal with a Big Pharma partner might provide. It also just as critically needed a partner to help it work out the complicated and expensive manufacturing and delivery processes for its novel compounds to treat drug-resistant HIV. In turn, Roche's alliance with Trimeris helped it more fully fill out its own portfolio of AIDS drugs, including its own internally developed compounds. In this case, internal research, development, and commercialization was not the solution for either company; a focused and tightly managed innovation partnership was. Their integral strategic alliance further powered core innovation for both firms.

-

Cisco Systems (see Chapter 5) never could have been built into such a dominating force in its core networking business solely on the merits of its own internal R&D. Exploratory alliances often paved the way for the company's subsequent stream of innovation by acquisition. It's certainly true that some of the acquisitions were overpriced and underperformed (especially the later ones), and some even outright failed. And it's also true that, in the wake of the technology bust, Cisco abruptly halted its M&A strategy and decided to refocus more on internal R&D. Nonetheless, a good portion of Cisco's earlier M&A approach was appropriate and effective given the technology and industry dynamics that prevailed throughout much of the 1990s. Aggressive innovation by acquisition worked well in the early and mid-1990s, even if it was less successful during the peak of the M&A binge that followed. As circumstances changed, Cisco rebalanced its portfolio of innovation sourcing and modes; it reconsidered and de-emphasized R&D by M&A, even as it nonetheless maintained acquisition as a very real option in its overall arsenal. When the smoke of the technology bust cleared, Cisco rekindled its R&D by M&A strategy, but with fewer pricey deals and many more bargains in the mix.

-

A need to focus on creating value through core innovation sometimes also suggests the need to spin out non-core innovation, regardless of (or perhaps precisely because of) how great its potential value might be. Microsoft and R.J. Reynolds (see Chapter 6) couldn't internally develop Expedia and Targacept, respectively, if they wanted to let these innovations fully bloom. Both sought to focus more on their own core businesses. Consequently, online travel leader Expedia.com and biopharmaceutical startup Targacept probably never would have had the chance to flourish as they did unless and until they were spun out and set loose from their corporate parents. In the process of divestiture, what were peripheral innovations for Microsoft and R.J. Reynolds became compelling core innovations for the newly freed and focused spinouts themselves.

In each of these cases, the emphasis is on core innovation, but the mechanisms for achieving the ends are complex and eclectic. A nostalgic return to internal R&D, therefore, is clearly not the answer and is certainly not our suggestion.

Instead, what we're recommending is a more open-minded but well-grounded approach to innovation: considering and using all the external, transactional options that are available as necessary and appropriate, yet with a strong internal R&D and new business development foundation. That is, companies need to develop the knowledge and skills to quickly identify and effectively implement opportunities for venturing, licensing, alliances, acquisitions, and spinouts. At the center of it all, however, they must build and nourish the core resources and capabilities that provide both strategic direction and competitive advantage for the entire constellation of innovation sources and modes they bring together. Core innovation, from whatever the source, must have focus and fit. It needs to be central and integrated, not peripheral and off-line. The core is the nexus that guides and enhances value creation and value capture for what otherwise would be an overly complex yet increasingly hollow holding company or venture capital fund.

The New Model ≠ Open Market Innovation

It's also important to emphasize that, in advocating proactive consideration and incorporation of external sources of innovation, neither are we advising undue reliance or too-narrow focus on Not Invented Here (NIH). Just as it's not all about internal R&D, nor does the emerging model revolve around loose concepts such as open-market innovation (i.e., better and faster R&D deal making). It's not centered around freeform and opportunistic external sourcing of innovation. As we discussed earlier in regard to licensing and acquisition, for example, there's no such thing as a free lunch. You tend to get what you pay for or, in many cases, you simply tend to pay too much.

Open-market innovation comes with its own price and risks. If you want ready-to-go innovation, you'd better have a thick checkbook. After you finish paying the purchase price, there might be little chance left of ever earning a decent return on your substantial up-front investment. If you're willing to take on a bit more of the risk of buying early stage innovation in exchange for a lower price, you'd better be prepared for unexpected setbacks and potentially heavy further development costs. The bottom line is that the only way to consistently earn superior profits from externally sourced innovations is to have some idiosyncratic advantage, especially a strong position in your own distinctive innovation core, that enables you to recognize, internalize, and commercialize these external ideas, technologies, and products in a way that no one else in the market could do nearly as well. That's how consistent, superior profitability is created and sustained.

Fueling Core Innovation from Inside and Outside

The recent experience of Procter & Gamble provides a clear example of the trend toward a more complex, but simultaneously more focused and better grounded, new model for innovation. By the late 1990s, Procter & Gamble hungered for growth and renewal. Judgments from inside and outside the company agreed that something needed to be done. Sales stalled. New product introductions were sparse and slow.

Procter & Gamble had fallen victim to what had been for decades a strong and effective internal R&D culture that had simply gone stale over time. It now was perceived as a slothful, conservative, over-engineering, and inward-focused organization. It had become a dated exemplar of the formerly well-honed, but now sputtering, model of internal R&D and organic new business development. A new management team under the leadership of CEO Durk Jager began implementing a broad-ranging global restructuring designed to power more innovation to market faster and more broadly. Simultaneously, like so many of its blue-chip colleagues, Procter & Gamble embarked on numerous experiments in corporate venturing: skunkworks, venture capital, Internet incubators, and more.

Unfortunately, all this radical action did not alleviate concerns about Procter & Gamble from either inside or outside the organization. Indeed, many soon worried that the proposed cure might be worse than the disease. The wrenching restructuring caused considerable disruption and discord within Procter & Gamble's vital country and brand units, which had long featured some of the best consumer goods expertise in the world. Much of Procter & Gamble's talent departed. Meanwhile, after only a couple years in progress, it seemed clear that Procter & Gamble's many novel corporate venturing initiatives were doing relatively little to revive Procter & Gamble's larger global prospects.

Jager announced disappointing results in early March 2000. The resulting massive drop in Procter & Gamble's decidedly blue-chip stock gave a preview of the imminent technology-led market crash yet to come. Procter & Gamble's shares fell by almost one-third in one day. Such a plunge would have been big news even for a speculative technology stock. The one-day drop was especially shocking for a supposedly stable and established company like Procter & Gamble.

In mid 2000, Procter & Gamble veteran A.G. Lafley took over as the new CEO and immediately set out to stabilize a restive organization. He did not abandon all of Jager's initiatives and ideas, but rather sought to better balance and clarify Procter & Gamble's innovation strategy. It was henceforth to be a strategy clearly centered on core innovation. But it was far from a nostalgic return to Procter & Gamble's old days and old ways. In fact, Lafley demanded that Procter & Gamble's innovators more aggressively seek core innovation wherever they could find it, both inside and outside:

The key element of P&Gs growth strategy can most simply be described as growth from the core. We are building on P&G's core foundation of categories and brands, customers and countries, capabilities and competencies to deliver long-term, sustainable growth. . . .

We're multiplying this capability by collaborating more extensively with external innovation partners. The vision is that 50 percent of all P&G discovery and invention will come from outside the Company.

The experience of Procter & Gamble's Crest brand shows how the new model came together in practice. The Crest Whitestrips tooth-whitening product had been developed internally and was introduced in late 2000. Also in 2000, the Crest Spinbrush line of low-cost battery-powered toothbrushes was acquired from Dr. John's Spinbrush, the fast-growing category pioneer and leader. Crest Whitestrips quickly grew to more than $300 million in sales in a strong new subcategory with even greater future expansion and extension potential. Meanwhile, the Crest Spinbrush line closely followed, soon doubling its post-acquisition sales to more than $200 million, also in a new subcategory with solid further potential for development.

Both innovations helped rejuvenate a seriously flagging core Procter & Gamble brand and category. Colgate, with a powerful core innovation of its own in the antibacterial Total line of toothpastes, had in the previous few years seized the lead from Crest and left it listless and wanting. Crest Whitestrips and Crest Spinbrush—one born and developed inside the company and one bought and integrated from the outside—both helped boost Procter & Gamble's core innovation in oral care and its core Crest brand. These successes were followed by other related innovations that boosted the entire brand and overall category.

As Procter & Gamble posted such solid gains, the company regained much of its luster. Its recovery was powered by innovations far beyond oral care—from Olay Daily Facials to Febreze fabric refreshener to Mr. Clean Magic Eraser and the Swiffer line of cleaning products. These other new additions also came from both inside and outside. Procter & Gamble's Prilosec OTC antacid product was the result of an alliance and licensing deal with European-based pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, for example. The venture tapped into Procter & Gamble's considerable consumer packaged goods resources and capabilities to take the former leading prescription anti-acid drug to a much broader, non-prescription customer base. Prilosec OTC's introduction in late 2003 was a notable success, reinforcing Procter & Gamble's reputation as the preferred partner for taking former prescription-only drugs to the larger over-the-counter (OTC) mass market.

With a series of solid base hits, Procter & Gamble shares soon nearly doubled from their 2000 lows. It was fitting that, in the wake of the technology and market bust, venerable old Procter & Gamble would chart a new path and begin to try to better outline and implement its own version of the emerging new model for innovation. Procter & Gamble chose to expand its portfolio of innovation sources and modes, even as it renewed the purpose and refocused the direction of its core innovation strategy.

Importance of Portfolio and Process

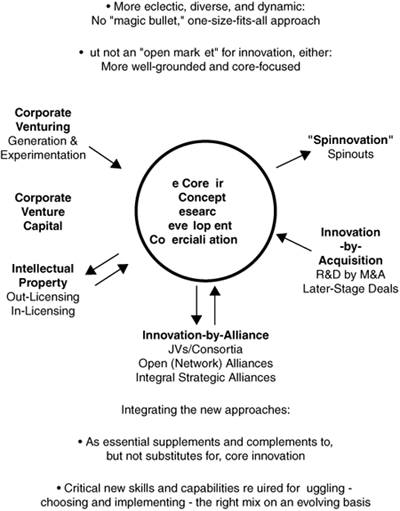

The emerging new model for innovation increasingly is about building and balancing a dynamic portfolio of innovation options—venturing, licensing, alliances, acquisitions, and spinouts—but all nourishing and continually renewing a vibrant core base. Organizations must look "outside" and be able to recognize and embrace Not Invented Here (NIH) when necessary. They need to get more comfortable and facile with externally focused, transactional approaches to R&D. At the same time, it's not all about ungrounded, deal-driven open-market innovation. The panoply of choices needs to be guided by core strategic concerns of focus and fit, and integrated with and leveraged by the firm's own solid innovation foundation. At the nexus of the entire dynamic portfolio is a thriving, bustling innovation core (see Figure 7-1).

Figure 7-1. Emerging new model for innovation.

Choosing and using each of the individual innovation options, as well as building and balancing the entire portfolio, is part of an ongoing process. Each individual option, as well as the entire portfolio, cannot be effectively pursued as static, one-time, adhoc investments. In a now common sort of progression, for example, investment in a startup might, in the future, transform into an alliance or in-licensing deal, possibly later become an acquisition, then perhaps be followed by out-licensing or spinout of excess, non-core innovation that's been acquired. Evaluating and implementing each approach therefore demands ongoing consideration of the specific objectives, resources, and context. Companies must consider and plan for the evolution of different choices, and of the entire portfolio. They must be prepared to change their tactics and strategies as circumstances dictate. Managing this complexity and dynamism is undeniably challenging, but this juggling act is key to surviving and thriving. It's how even established firms can keep up with—or, better yet, even stay ahead of—the innovation curve.

Innovation Redeemed and Revitalized

So, where does this journey through the ups and downs of various innovation fads and fashions finally leave us? Clearly, there is no simple, quick, and universal solution to fuel innovation all the way from conception to commercialization, especially not for all organizations in all situations. In this sense, all the innovation fads and fashions overpromised and underdelivered. Often, they were recommended and applied at the wrong time, or for the wrong reasons, organizations, or situations. They were promoted and adopted with little attention or concern for the critical nuances of their implementation and evolution.

In contrast, we offer no pretense that this is a "recipe" book. Innovation cannot be reduced to simple templates or standard prescriptions. We do, however, believe that all the approaches to innovation present inherent tensions and conflicts, problems and pitfalls, caveats and conditions that beg to be heeded. As we have explored throughout this book, the "how" of innovation matters as much as the "what" in determining innovation success and failure. Innovation initiatives need to be designed up front to have the best chances of success, not set up to fail.

In each chapter, therefore, we provide an overview and summary of key lessons learned in regard to each particular innovation tool or tactic: When is this or that approach a good bet or a worse bet? What are the pitfalls to watch out for and avoid? What are the key details to consider and plan for, thinking ahead? What are the better and worse approaches toward maneuvering and managing the critical details of implementation? In addition to these specific issues, there also are a few more general conclusions that can be drawn from our larger exploration of the innovation landscape.

Certainly, the experiences of the past few years leave one a bit more skeptical, but perhaps also more hopeful. The hope flows from at least two sources. First, these experiments and experiences ultimately have led to a renewed and more coherent focus on core value creation. Second, each of the innovation fads and fashions, in their own way, had much to offer as part of building a more diverse and dynamic portfolio of innovation options and choices. Each idea brought essential new value, a vitally useful new tool and tactic, to the innovation workshop, even if many kinks had to be worked out in practice.

Building from a solid foundation of core innovation, in fact, all these tools and tactics offer more realistic and effective solutions to the most critical innovation challenges of companies big and small alike. They offer real hope to large and established organizations seeking new ways to create and capture value without abandoning their own unique strengths and legacies. They likewise offer new approaches by which young, entrepreneurial startups can minimize their weaknesses and leverage their own novel resources and capabilities in order to grow and prosper.

In an increasingly complicated, fast-moving, and technology-driven global economy, deft mastery of these varied approaches will only grow more important. This means being able to craft and balance more complex portfolios, and manage evolving processes, in which any or all of these innovation tools and tactics might play important roles. The task is made even more complex by the fact that innovation increasingly crosses borders of all kinds, taking on new international dimensions and involving, what is for many organizations, still relatively unfamiliar global territory. Ideas and talent are everywhere. This fact will drive everything from increased cross-border in-licensing and out-licensing, to increased corporate venture capital investments in (and from) places like China and India, to more international alliances and acquisitions. It's a brave new world of more diverse and dynamic innovation taking shape.

The emerging new model we've described is not a simple panacea. Nor is it some fantastically novel, supposedly breakthrough scheme (read: fad or fashion). But it is a more realistic, effective, and sustainable approach. And it is surely the future of innovation.