Anyone can edit Wikipedia. Most of the time that’s a good thing—millions of people have made positive contributions to the largest group-writing effort in human history. Then there are the problem children: those who can’t resist the urge to deface an article, or delete all its content (a practice known as blanking a page), and those who add incorrect information, deliberately or by mistake. Fortunately, Wikipedia has robust change-tracking built into it: Whatever one editor does, another can reverse, returning an article to precisely what it was before.

Apart from vandalism, as an editor you’re likely to want to see what other editors do to articles you’ve edited, whether they’re on your watchlist (Wikipedia’s Standard Watchlist) or not. While Wikipedia’s change-tracking system isn’t hard to understand, you’ll probably find it isn’t totally intuitive. In this chapter you’ll learn how to quickly read through even a convoluted page history, how to see what’s happened since you last edited an article, how to restore an earlier version of an article with just a few clicks, and how to deal with a problem edit followed by other edits you don’t want to delete.

When you’re working on, say, an Excel spreadsheet, you can’t turn back time and look at what the document was like last Tuesday at 10:05 a.m. Wikipedia is different—its database has a copy of every version of every page ever created or edited. If you click on a page history tab, you can see the text on that page at whatever date and time you pick. The page history also shows you every single edit since then (or before then, for that matter).

Keeping a copy of every revision of every page means storing a lot of data. But it’s integral to Wikipedia’s success. Here are the main benefits to having a record of everything:

Responsibility. Page histories show who did what to a page, when, and often even why. Thousands of Wikipedia editors are warned, every day, for inappropriate editing. Hundreds of user accounts are blocked every day for vandalism, disruptive editing, spamming, and so on. Page histories help identify problematic edits and problem editors.

Reverting. You can use page histories to easily revert (that is, reverse) another editor’s inappropriate edit—or even your own edit, if you’ve made a mistake. (More on reverting on Reverting Edits.)

Reputation. Because your edits will be visible to everyone, forever, you own them forever. Hopefully, you’ll think twice before damaging the good work of others. That’s how most editors behave, at least.

Liability. The Wikimedia Foundation claims it isn’t legally liable for any deliberately false information that an editor adds to an article, and legal cases to date have supported that position. Instead, it’s the editor who’s liable (though none have ended up in court yet). A page history, by establishing exactly who changed the article, what she changed, and when, makes it clear that the Foundation didn’t create or edit a page—individual editors did.

Tip

If you inadvertently add something to a page that you later decide shouldn’t be there—a home address, a complaint about your employer, or other private information—you need to do more than just edit the page again and delete that information. Anyone visiting Wikipedia can read the previous version of that page, where that information still exists, simply by going to the page history and opening a prior version of the page. To make something completely inaccessible to other editors and readers, you have to ask an administrator to help. (See Wikipedia:Selective deletion, shortcut WP:SELDEL, for details.) Even then, the problematic version of the page is still in the database, but only administrators can read it.

If you want to look at individual edits to and prior versions of a page, near the top of the window, just click the “history” tab. The list that appears shows the most recent edits/versions—up to 50, if the page has been edited that many times. The list’s top row is the most recent version of the article; the bottom row is the oldest, as you see if you look at the dates and times.

You can use a page history in one of three ways:

You can simply read it to get a general sense of who did what and when.

You can get a sense of how the text has changed by looking at individual edits, or a group of consecutive edits.

You can click the date and time listed for a prior version of the page to read that particular version.

This section shows you how to read and interpret a page history in detail.

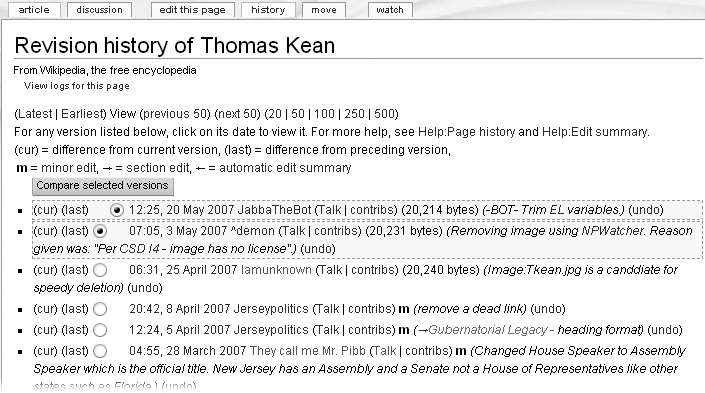

You can learn a lot by simply reading a page history. Figure 5-1 is a snapshot of the history page for the Wikipedia article on Thomas Kean. If you’ve never seen a history page before, it probably looks confusing. But each of its many elements has a simple purpose.

Figure 5-1. Here’s a typical page history. Only six versions (edits) are shown, but a history page normally lists the first 50. Edits older than the most recent 50 are listed onto separate pages. You can specify the number of edits listed on the first page—and any subsequent pages you look at, with older edits, by clicking the 20,50, 100, 250, or 500 links near the top.

Here’s a grand tour of the page history for the Thomas Kean article in Figure 5-1:

On the left, the first few columns—(curr), (last), and the radio button—let you tell Wikipedia which versions of the article you want to compare, which you’ll learn exactly how to do on Seeing What Changed. If you’re not comparing versions, you can ignore these columns—they’re always the same.

Next comes the time and date a version was created (or, in other words, the time and date an edit was saved). The time shown is Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), formerly known as Greenwich mean time. UTC is 5 hours ahead of Eastern Standard Time in the U.S., and uses a 24-hour system of notation rather than a.m. and p.m. So, for example, 19:05 UTC is 14:05 EST, which is 2:05 p.m. EST.

Note

You can change the times displayed in history pages, if you want, to your local time rather than UTC. For details, see Date and Time.

Notice that the six versions span almost 2 months. From that you can infer that the article’s subject isn’t very controversial; the article doesn’t get a lot of readers (because if it did, a few of them would probably edit it a bit); and there hasn’t been much in the news about this person during the 2-month period of these six edits.

Note

The Wikipedia site gets such an incredible number of page views that the edit counters built into the software (which display the number of times a page has been viewed) have been turned off, since they were slowing down the servers. So you can’t know for sure if this article was viewed a lot or only a little in the 2 months examined here—you can only speculate.

To the right of the date is the name of the editor, with links to the editor’s user page (click the name), the editor’s user talk page, and to the “contribs” page that lists that editor’s edits (called contributions). Sometimes when evaluating an edit, you want to see what else the editor has done. If so, you can follow the link to the user talk page (to look for warnings posted by other editors) or the link to the user contributions page (to look at the number of edits, what articles were edited, and even—via a link on that page—whether the editor has been blocked by an administrator to prevent further problems).

The upper three rows (versions) in Figure 5-1 list the count of bytes (a byte is roughly one character) in those versions. Byte counts can tell you if much has changed. In this case, not much—the most recent and second-most-recent edits removed a net 17 and 9 bytes of information, respectively.

Note

If you’re wondering why the other three rows don’t list byte information, it’s because the change in software that added the byte count happened in mid April 2007.

The lower (older) three listed versions have a bold “m” after the editor information, indicating a minor edit. Generally, minor edits aren’t controversial or problematical. However, since editors—not the software—decide whether an edit is marked as minor, an “m” isn’t 100 percent guaranteed to be true.

Towards the far right of each row is the edit summary. As discussed on Previewing, this text is how the editor describes that edit. Several things are worth noting:

In the oldest edit in Figure 5-1, the editor went to some length (175 characters, to be exact) to explain the edit. The editor was probably concerned that other editors might think the edit was a mistake, and was trying to lessen the probability that the edit would be reverted (Reverting Edits).

Two of the edit summaries include wikilinks (in blue) within the edit summaries. Wikilinks in edit summaries work the same way as wikilinks in articles, and you create them the same way (with paired square brackets around the page name). The same goes for piped links (How to Create Internal Links).

In one edit summary, the words “Gubernatorial Legacy” are gray rather than black, with a right-pointing arrow in front of the text. As discussed on Editing Article Sections, if an editor selects only one section to edit, rather than the whole article, then the software inserts the name of that section into the edit summary’s beginning.

Tip

That right-pointing arrow in front of the section name is actually a link. If you click it, then you go directly to that section in the current version of the article in reading mode. Or, to be more precise, you go to that section as long as no editor has subsequently changed the section’s name. (If the section name has changed, you’ll go to the top of the article.)

Finally, each row ends with an “undo” link. This link lets you revert the edit listed in that row. You’ll learn how to use it later in this chapter (Option 1: Undo).

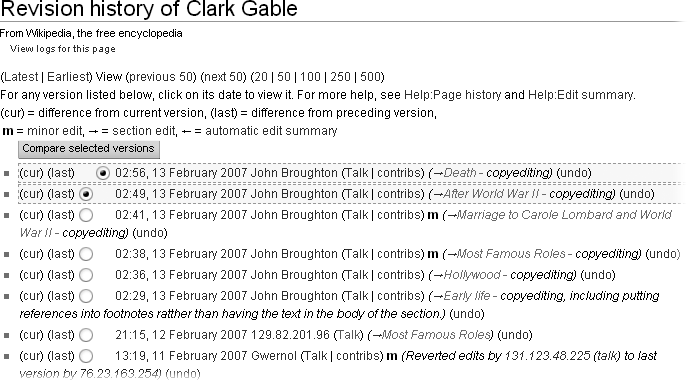

Moving from politics to movies, consider Figure 5-2, another screenshot of a page history, this time for the article on Clark Gable. Now that you know what all these little words and links represent, you can use them to get a sense of how the page has evolved over time. The page history gives you facts. You have to figure out what it all means.

Figure 5-2. This page history excerpt shows only eight versions. Right away, you can see that one editor has been busily working away.

Reading the page history for the Clark Gable article, you’ll notice the following facts and make some related inferences:

The top six edits were done by the same editor. Sometimes that indicates inexperience: Wikipedia veterans often do some editing of a page, click the Preview button to see the change, do more editing, preview again, and so on, before actually saving the changes to create a new version.

Or perhaps the editor was saving changes in small increments to avoid edit conflicts (see Dealing with an Edit Conflict). Working in small, incremental edits is a good idea when lots of edits are happening, on popular pages and page about current events. In Figure 5-2, the information in parentheses (the edit summary) shows the editor worked on six separate sections, perhaps to make it easier for others to see what he was doing to a long-established article.

For five of those six edits, the editor didn’t offer much explanation in the edit summary (all he wrote was “copyediting”). Presumably, he thought that other editors wouldn’t find the edits controversial, so there wasn’t any need for lengthy explanations.

The seventh edit was by an anonymous editor, not a registered user. For this edit, the “talk” link is red, indicating that this editor’s user talk page doesn’t exist yet. (If it did, the link would be blue, like the others.) User talk pages are one place where editors communicate with each other (User Talk Page Postings); only in very rare circumstances do established editors lack a user talk page. A red link is a red flag. It means this editor probably has very few edits, which greatly increases the likelihood that this edit is not constructive.

The anonymous editor didn’t explain what her edit was about. The edit summary has only the section name (“Most Famous Roles”). That’s another indication that this person probably hasn’t done much Wikipedia editing.

You can see that the most recent editor (who did the top six edits) didn’t alter the edit made by the anonymous editor, because none of that editors’ six edits were to the “Most Famous Roles” section. Did that editor look at the anonymous edit and decide it wasn’t vandalism, spam, or the removal of good information, and so he didn’t revert it? There’s no way to know for sure. In the next section, you’ll look at what actually changed with this mysterious edit. If you care enough about an article to take a look at its history, you probably want to take a peek at any such potentially questionable edits you come across.

Once you’ve got an overview of a page history, you can stop right there, or take it a step further—look at actual edits to see who changed what. If a glance through the page history doesn’t make you suspect vandalism (for example, vandalism is unlikely if the last edit was more than a week ago, and by a registered editor with a user page and a user talk page), you can go ahead and edit the article without probing more deeply. But most of the time you’re going to be curious about one or more specific (usually recent) edits, for one reason or another. In addition, when you’re starting out, looking at others’ edits is a good way to learn about how to edit Wikipedia.

Fortunately, you could pretty quickly go ahead and look. When you want to see what one or more editors have changed in an article, you ask the software to compare one version of the page against another version. The resulting output, the difference between versions, is the actual edit.

Note

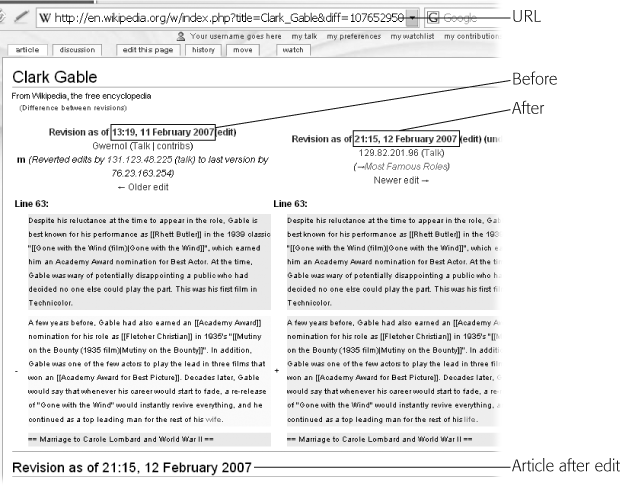

The technical term for the difference between any two versions is a diff. You may run across it, for example, when you want to report a problem editor and page instructions, or an administrator, ask you to “provide diffs” that demonstrate the problem. One way for you to remember what this term means is that the URL of the output includes “diff=”, as shown at the top of Figure 5-3.

Any single edit of a page is the difference between one version of a page (one row in the page history) and the version immediately before it (the row below it). You have two ways to get a diff for a single edit. The slow way is to use the two columns of radio buttons, and then click “Compare selected versions” (or press Enter). The fast way is to click the “last” link, on the left side of the version you’re interested in.

Time to take a closer look at that anonymous edit in Figure 5-2 to see whether it was vandalism. When you click “last” on the row for the edit of 21:15, 12 February, you get something that looks like Figure 5-3.

Figure 5-3. When the Wikipedia software compares two versions of a page (that is, the effects of one or more consecutive edits), you see a page like this one. Not all of this “diff” is shown—it actually includes the full version of the page after the edit listed in the right column at the top. You can turn that off— just see the top side-by-side comparison —if you want, by checking “Don’t show page content below diffs” in the “Misc” tab of your My Preferences page, but most editors don’t—it doesn’t really save much time for the diff page to load, and sometimes having full context is helpful.

Here’s how to read the various elements on a diff page:

Your browser’s address bar gives the output page’s URL. When instructions on an administrative page say, “provide diffs,” they’re asking for URLs like this.

Near the top of the output page is information about the two versions of the Wikipedia page being compared: the version just before the edit, and the version that resulted from the edit.

The heart of the output page is the before-and-after comparison showing what text was added (nothing, in Figure 5-3), deleted (nothing), and what was changed (just one word). This side-by-side comparison is the actual edit.

For context, the side-by-side comparison shows a paragraph or section heading immediately above the paragraph where the change was made, then the paragraph with the change, and finally the next paragraph or the heading of section below the change.

When a word has changed, the software shows that word in bolded red for emphasis: in this case, “wife” (before) and “life” (after). So it turns out that the edit was constructive—it fixed an incorrect word that was a typo, Freudian slip, or somewhat subtle vandalism.

At the bottom of the diff page is the article as it appeared at 21:15, 12 February (only part is shown in Figure 5-3, to save space). You may not even need to even look at this article snapshot, but it can be helpful for figuring out things like exactly where an edit occurred within a long article.

Note

If you’re looking in a page history for an edit made by a particular user, and don’t see the editor’s name in the first fifty edits, your instinct might be to click “next 50”. Try clicking “500” instead. That displays the most recent 500 edits (not the next 500, but rather the most recent 500 edits). The extra time for Wikipedia’s server to find and display 500 edits rather than 50 is minimal—perhaps a second or two. But calling up 500 edits can save you a lot of time if the edit you’re looking for is 150 or 200 versions deep, which can happen with a very busy page.

You now know how to see what changed in a single edit. But often you’ll want to see what changed in a group of consecutive edits. For example, suppose you edited an article 2 days ago and want to see everything that’s changed. If there were 10 edits since then, you would want to see, in one place, everything that’s changed; you don’t want to have to do 10 different diffs. Or suppose several different anonymous editors have edited an article recently. By looking only at the net affect of all the recent edits, you don’t have to bother dealing with vandalism by one editor, if another editor has already fixed it.

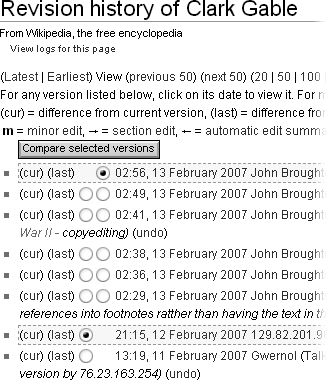

To take Figure 5-2 as an example, suppose you want to see in a single place what editor John Broughton did in his six edits. You can view multiple edits simultaneously in one of two different ways: a quick way that works only in limited circumstances, and a slower way that works anytime. Figure 5-4 shows the tools for both options.

Figure 5-4. To see what editor John Broughton actually changed in his six edits, you can use the two rows of radio buttons to select a set of consecutive edits, as shown here. It’s the slower way to view multiple edits, but you can use it anytime. If the edits you want to view happen to include the most recent version, a single click on the “cur” link next to the earliest edit you wanted to include would do the trick instead. Since you often focus on the most recent edits, that shortcut can be useful.

If the 02:56, 13 February 2007 edit was the most recent, you can quickly see what changed in the six edits of interest in Figure 5-4 when you go to the row for the 21:15, 12 February version (the one just before the edits of interest), and click “cur”. That click tells the software to compare that version to the current version; the difference between the two versions, of course, is the six edits.

The quick way’s limitation, of course, is you can only use it when you’re comparing the current version to a prior version—that is, you’re looking at a consecutive group of edits up to and including the most recent. The quick approach doesn’t work if you want to compare one old version to another old version of the article, to see what changed between them; for example, if an edit (according to its edit summary) fixed vandalism, but you suspect it didn’t completely correct the vandalism of the immediately proceeding edit. If you can’t use the quick way, the slower (but universal) way to see what happened in a group of consecutive edits is to use the two columns of radio buttons. In the first column, select the “before” version; in the second column, select the “after” version (Figure 5-4). Then press Enter or click “Compare selected versions”.

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, you can use a page history in three ways: Read it to get an overview, view and compare edits, or get to any prior version of the page. That third option is the least useful, since you can better figure out what’s change on a page by looking at the actual edits, but you can see what an article used to say at an earlier point in time if you really want to.

To see what text in any specific prior version of a page, on the history page, simply click its time and date. Bear in mind that Wikipedia stores the text of a page version in its database, but doesn’t keep a record of any images or templates that were on the page at that time. Instead, the software recreates a prior version of a page inserting the current image and templates into it.

In other words, you’re not looking at the equivalent of a snapshot of an older version of a page. But that usually doesn’t matter, since it’s almost always the text you’re concerned about, rather than images or templates. (If you want to see what the image looked like at the time, click the image, which takes you to the history page for that image. Similarly, if you’re concerned with the template, click it to go to history page of the template to see what, if anything, changed before the current version.)