The processes described in this section may seem like bureaucracy run amok, but in fact they’re an efficient, logical way to escalate a matter until it’s solved, whether that’s because an editor changes his ways, quits Wikipedia, or gets blocked.

If you’re the subject of a personal attack or significant incivility, both you and the other editor determine what will succeed in stopping recurrences of the problems. If you fan the flames by attacking back, that’s a violation of rules in its own right, and will probably get you your own warnings. In that case, the matter may not get resolved until it goes to the highest level of community decision-making in English Wikipedia—the Arbitration Committee (The Arbitration Committee). If both you and the other editor are reasonable people (and you’ll certainly encounter editors who aren’t), you may be able to solve the problem by simply talking it out on user talk pages.

What happens after your first response depends on what kind of person you’re dealing with. So circumstances decide which of the following measures to choose. You’re certainly not required to use them all.

Personal attacks almost always occur on your own user talk page or on an article talk page. There may be some obvious lead-in (you and another editor have reverted each other’s edits in a content dispute, for example) or the attack may come out the blue (from someone whose edit you’ve reverted as part of vandal-fighting, for example). Regardless, there it is, staring you in the face. It may be a graphic insult, or a passive-aggressive jab. The first thing you should do is nothing. That’s right. Don’t respond at all until your emotional reaction has passed. Then you can consider your options.

The standard human response to an attack is hardwired into your brain—fight or flight. When you’re in danger, your emotions tell you to act immediately. Your emotional system is much faster than your logical system. Quick decisions are emotionally driven, not the product of rational thinking. So before your typing fingers fly into action, say to yourself: Those are just words on a computer screen. I don’t have to do anything right now. I have all the time I need, to think this through and do the right thing. I don’t need to do the first thing that comes to mind.

Wikipedia doesn’t operate at real-world speeds. Take a break, come back in an hour or a day, work on something else, breathe deeply, have a nice cup of tea—there isn’t any rush.

In the real world, responding to an attack is considered standing up for yourself. In Wikipedia, editors who attack back are considered part of the problem. Attacking an editor whom you think attacked you turns Wikipedia into a personal battleground, which is against policy. As WP:NOT puts it: “If a user acts uncivilly, uncalmly, uncooperatively, insultingly, harassingly, or intimidatingly toward you, this does not give you an excuse to do the same in retaliation.”

Your goal in dealing with this type of problem is to get the other editor to change her behavior, and if she doesn’t, have her removed from Wikipedia. If you succeed in the first, or are efficient in doing the second, that’s what standing up for yourself in Wikipedia is all about.

An editor who resorts to uncivil comments and personal attacks loses credibility at Wikipedia. If the editor’s arguments were sound and logical, why would he need to get personal and emotional? You can gain credibility, assuming that what occurred wasn’t a clear and convincing personal attack, if you simply ignore it. An editor may just be having a bad day. Don’t reinforce snarky behavior by responding to it.

How you ignore incivility depends on where it occurs. If it’s a posting on your user talk page, you can delete it or archive it (see Editing or Deleting Existing Comments). If it’s a posting on an article talk page, you can see whether someone else responds to it (with a comment or a warning), or if another editor ignores it and discusses the non-personal aspects of the posting.

If you’re not sure whether or not to respond, wait a full day or so, and see whether anything else happens.

As discussed in Chapter 8 (???), article talk pages are for discussing articles, not editors or their behavior. That said, if you’ve decided to post a warning or request that the editor be blocked (see Actions by the community), it’s helpful to leave a response to that effect on an article talk page. That way, other editors know the problematical posting is being dealt with. A comment like this is appropriate:

This violates [[WP:NPA]]; I’ve posted a warning at [[User talk:Name of problem editor]]. ~~~~

Or this:

I’ve reported this violation of [[WP:NPA]] at [[WP:AN/I]]; repeat problem. ~~~~

If you respond at all, stick to the facts. If particular wording wasn’t in accordance with a Wikipedia policy, that’s a fact. If you speculate on the editor’s motives for writing something, that’s your opinion. The guideline Wikipedia:Etiquette (shortcut: WP:EQ) stresses that text on a screen may comes across as rude, when you can’t hear the voice or see the facial expressions of a person sitting in front of you. An ironic joke may come across as a full-on insult. Again, assume good faith. Don’t assume someone’s out to get you. Similarly, be sure your own writing is brief, clear, and to the point. Avoid saying things that someone could take the wrong way.

Your goal isn’t to hammer the other editor into submission (which rarely works, anyway), it’s to get her to realize that her actions have consequences. If the other editor has improved articles and shown reason in other edits, that’s all the more reason to assume good faith. You’re not helping Wikipedia by making things unnecessarily unpleasant and driving her away.

The correct approach to warning an editor about behavioral violations is somewhat similar to warnings about vandalism, as discussed on Choosing the Warning and Warning Level. Start by looking at the warnings that others have posted on the user talk page, if any. Then take a look at the user talk page’s history—the user may have deleted warnings. Next, take a look at the User contributions page: Is this a regular contributor or someone with very few edits? (It’s harder to tell with anonymous IP accounts; just look at the last week or two of postings.)

Here are some types of editors you might encounter, and the appropriate responses:

An anonymous IP editor with no other postings. If you get a single drive-by attack, it’s best to just drop the matter. Your warning probably isn’t going to do any good. If the posting is part of an ongoing series, post something at Wikipedia:Administrators’ noticeboard/Incidents (shortcut: WP:AN/I).

Relatively new editor, lots of warnings. Post a standard warning template from the WP:WARN page, following the procedure laid out in Chapter 7 (Posting the Warning). If the editor has already hit level 4, and then attacked you, take the matter to WP:AN/I rather than posting a warning.

Regular editor, lots of contributions, very few problems. Depending on how egregious the attacking post was, tailor your posting from nothing at all to a measured response. Reasonable wording is, “Maybe I’m misunderstanding your post, but it seemed to me that saying I need to repeat the third grade crossed the boundary of [[WP:CIVIL]].”

Tip

Before you post any kind of response, double-check to make sure you’re posting to the correct user page. Don’t use a template on an editor who has been a regular contributor for a long time.

If you post a warning and the other editor comments that it’s not justified, don’t argue. If what the other editor says seems to have merit, it’s fine to reconsider your warning (and, if you change your mind, do a strike-through, as described on ???). If the other editor says your warning is uncivil, or amounts to a personal attack, or violates AGF, ignore it. Those allegations are considered wikilawyering, and it doesn’t impress administrators. Ultimately, the matter comes down to the future behavior of the other editor, future warnings he gets, and what administrators decide when they read the edits that caused the warnings. You’ve made your contribution to reducing future problems by posting a warning, and that’s what counts.

If you’re still struggling with some of the underlying concepts of the advice above, reading a couple of these essays may help:

Wikipedia:Avoid personal remarks (shortcut: WP:APR)

Wikipedia:No angry mastodons (shortcut: WP:NAM)

Wikipedia:Staying cool when the editing gets hot (shortcut: WP:COOL)

Most of the time, incivility or a personal attack is a one-time occurrence. But if it’s repeated, and you think you need help dealing with it, you have a number of informal options. Use one or more of these options before turning to the formal process for dealing with problem editors.

You’ll find instructions at the top of the main page of each option listed in this section. Read them. Other editors appreciate it when you read and follow instructions for asking for help.

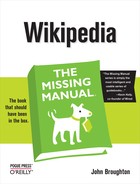

Wikipedia:Editor assistance (shortcut: WP:EA) is an informal way of getting one-to-one advice, feedback, and counseling from another, more experienced, editor. You can actually get advice in two ways: Post something on the Requests page, or contact one of the listed editors on the primary page (Figure 11-4).

Figure 11-4. At the Editor assistance page, you can post an open request for any editor who wants to assist you, or you can pick an editor from a list (lower down on the page than shown here). In either case, you can get a personal consultation about any editing situation.

You may think that asking another editor for assistance is an intrusion on her time. It is, in some sense, but for many editors, offering advice to a sane, reasonable person can be a welcome change of pace from what they normally do, particularly if they’re administrators.

Note

If you decide to go the route of asking an editor directly for advice, be sure to check his User Contributions page. You want to pick someone who has edited in the last day or so, not someone who has largely stopped editing but has forgotten to remove his name from the list.

Wikipedia:Wikiquette alerts (shortcut: WP:WQA) is “where users can report impolite, uncivil or other difficult communications with editors, to seek perspective, advice, informal mediation, or a referral to a more appropriate forum.” If you post here, you may get advice from just one editor, or from several.

You can certainly try “Editor assistance” first, then “Wikiquette alerts,” though the two actually overlap. Just don’t post in both places simultaneously. That’s forum shopping, and most editors consider it bad form. If you’re debating which to choose, know that EA is faster, but WQA has more activist editors who do things like post warnings themselves.

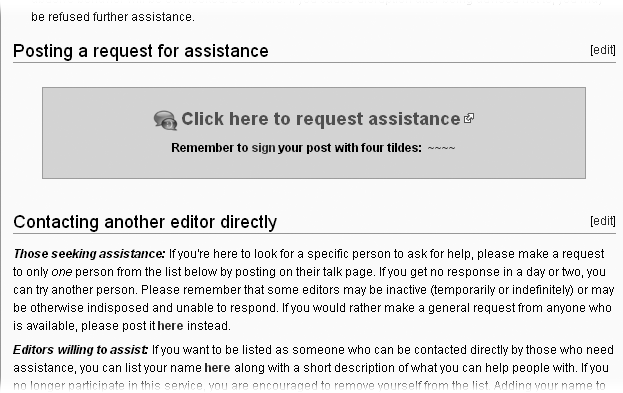

The Wikipedia:Mediation Cabal (shortcut: WP:MEDCAB) provides informal mediation for disputes on Wikipedia. (See Figure 11-5.) Their page states, “You must already be having a discussion. We cannot start a discussion for you.” In other words, both you and the other editor must be willing to participate in such informal mediation. It never hurts for you to offer the other editor this option. It’s a demonstration that you’re trying to assume good faith; just don’t expect instant agreement. (The catch-22 here is that if you and the other editor are both willing to go into mediation, most of the time you’d be able to work out a reasonable solution without needing mediation. )

Figure 11-5. The Mediation Cabal is an unofficial group of editors who offer informal mediation. The “cabal” aims to help with disputes in a way that minimizes administrative procedures. If you ask for help, you get help, but all the editors involved in a dispute must agree to participate.

People use this type of informal mediation more frequently for content disputes, as discussed in Chapter 10 (Chapter 10). If a mediator suggests that both you and the other editor agree to do (or not to do) certain things in the future, don’t protest that the other editor is at fault, not you. If what the mediator proposed isn’t onerous, and getting the other editor to agree hinges on whether you agree, then agree. You won’t help yourself by arguing. Your goal is to get the other editor to change her ways, not to have a mediator declare who’s at fault.

Wikipedia:Community enforceable mediation (shortcut: WP:CEM) was an experimental alternative where editors could resolve disputes by negotiating and agreeing to binding agreements that mimicked arbitration remedies. Like informal (Cabal) mediation, above, it required all parties to agree to participate in mediation. Unlike less formal mediation, however, if agreement is reached, administrators would enforce it.

The process was opened for cases in March 2007 and shut down (marked as inactive/historical) in December 2007. Five cases were submitted; none resulted in enforceable agreements.

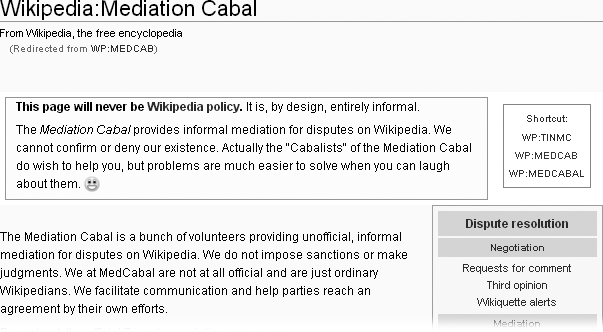

Wikipedia:Administrators’ noticeboard/Incidents (shortcut: WP:AN/I) is for only serious, repeat attacks where the editor has received clear warnings and is ignoring them (Figure 11-6). You go here if an editor has engaged in a personal attack after receiving a level 4 warning, or if you’ve posted a warning and then a higher level of warning, and the editor persists in violating the NPA policy. (You could, in theory, continue to escalate your warnings, but two is enough.)

Figure 11-6. The page Wikipedia:Administrators’ noticeboard/Incidents is for reporting and discussing incidents on the English Wikipedia that require administrators’ intervention. But if you think there is a more specialized noticeboard for reporting the incident, or it is a type of abuse for which there is a specific page, or you need a type of assistance for which there is a specialized page, then you should go there rather than post at WP:AN/I.

If you’re unsure that the problem is serious enough for AN/I, don’t go there—the page gets enough traffic as is. If you do post to the noticeboard, be sure to include a succinct description of the problem, together with roughly a half-dozen diffs (Seeing What Changed) showing problem edits.

Note

Report any cases of aggressive harassment (see WP:HAR) or attack pages (WP:ATP) to this noticeboard without waiting to see if warnings are useful. If behavior is egregious, deal with it promptly.

If the problem continues, and you’ve exhausted your informal options, Wikipedia has two formal processes for dealing with problem editors: a Request for Comments regarding user conduct; and binding decisions by the Arbitration Committee, the highest level of community decision-making within the English Wikipedia.

Both of these processes are time-consuming: Each can take several months to play out, and the evidence presented and arguments made can be voluminous. Fortunately, only a small percentage of disputes are so entangled that they go to arbitration; RfCs are much more common.

Note

Chapter 10 (Formal Mediation) described a third formal process, action by the Mediation Committee. Requests for mediation (shortcut: WP:RFM) are limited to content disputes, so they’re not included in this discussion of personal attacks and incivility.

The cases opened at Requests for comments – User conduct (shortcut: WP:RFCC) require that at least two editors have contacted the editor whose conduct is being questioned, on that editor’s user talk page or the talk pages involved in the dispute, and tried but failed to resolve the problem. The two (or more) editors certifying the dispute must be among those who attempted to resolve the matter. Filing an RfC is not a step to be taken lightly or in haste. Informal ways of resolving disputes (like talking it out) are preferable, but if they don’t work, then an RfC provides the last chance for an editor to come to his senses.

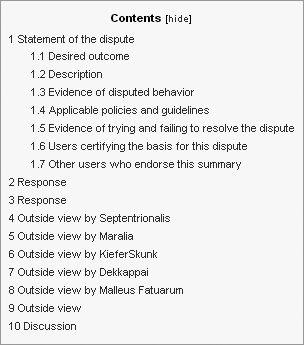

There are aspects of a court case to an RfC, although it’s by no means a legal matter. Editors present evidence (diffs), make statements, and endorse viewpoints. If you’re doing a user conduct RfC against another editor, be clear and succinct, and present compelling details about who said what, when, and where. Figure 11-7 shows a table of contents for a typical RfC user conduct case.

Figure 11-7. A Request for Comment on user conduct is a cross between a legal case and a public hearing, with evidence, responses, and statements of view from uninvolved editors. Here’s the table of contents of an RfC that’s been open for about 6 weeks.

Editors named in an RfC are expected to respond to it. If the matter goes to the Arbitration Committee (see The Arbitration Committee), failure to respond is a factor that arbitrators take into consideration. Within an RfC case, though, there’s no way to compel an editor to comment, and no penalty for failing to do so. But as in real life, failure to respond tends to be seen as an admission that the editor has no good explanation or defense for her actions.

An RfC will not result in any enforcement action by administrators. The ideal outcome is that the involved editors, in view of comments by others that are posted in the RfC, find a way to agree to what they will and won’t do in the future. An RfC may even result in apologies offered for past behavior. So even if an RfC shows an overwhelming consensus of opinion by uninvolved editors who comment in the RfC, resolution depends on the problem editors accepting that such a consensus is valid, and that they need to change. If an RfC doesn’t result in voluntary changes, the final step (if the problem continues) is the Arbitration Committee.

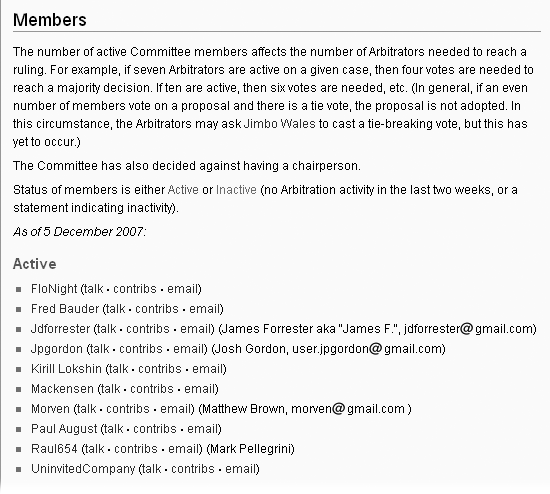

A Request for Arbitration (shortcut: WP:AFAR) is the last step of dispute resolution on Wikipedia. The Arbitration Committee (see Figure 11-8) makes binding decisions. In most ArbCom cases, at least one editor gets banned from editing Wikipedia for at least a year, and rulings against multiple editors are common.

Figure 11-8. The Arbitration Committee consists of volunteer editors; the English Wikipedia is essentially a self-governing community. Committee members are appointed by Jimmy Wales, based on the results of annual elections. The fifth annual elections were held in December 2007; roughly a third of the Committee is elected each year, for 3-year terms.

The Arbitration Committee consists of volunteer editors. Committee members are appointed by Jimmy Wales, who owned Wikipedia before giving it to the Wikimedia Foundation, which he created. The appointments are based on the results of advisory elections held annually, where registered editors at Wikipedia express support and opposition to the candidates. Wales does not consider himself bound by the results of the elections, but he’s generally appointed arbitrators from among the candidates with the highest percentage of positive votes.

Except for a few cases involving serious problem actions by one or more administrators, the Arbitration Committee requires that cases must first have gone through the RfC process. The Request for Arbitration policy states that “The Committee considers community input from the RFC process both in determining whether to accept a case and also in formulating its decisions.”

The likelihood that you’ll ever be involved in a case before the Arbitration Committee is small, unless you’re an active editor of articles whose basic subjects are controversial. In 2006 the committee handled 116 cases. This book doesn’t cover the intricate details of filing and arguing a case. For now, know that this final resort is there for extreme cases. If editors don’t voluntarily agree to behave properly, and if their behavior is not so egregious that an administrator blocks them, then the Arbitration Committee process is the final step that the Wikipedia community can take to prevent an editor from disrupting Wikipedia.