CHAPTER 14

Productivity

There are some structural issues with our economy, where a lot of businesses have learned to become much more efficient with a lot fewer workers. You see it when you go to a bank and you use an ATM; you don't go to a bank teller.

—President Barack Obama, June 14, 2011

Do computers and similar technologies make economies grow? Do these technologies displace workers? How might information and technology improve economic performance, whether at the firm, sector, or national level? Because previous technologies augmented physical power and mastery, they offer only limited insight into the impact of technologies that expand people's abilities to remember, to know, and to connect.

The debate over the relationship between automating technologies and unemployment is not new, as Adam Smith's famous example of pin making goes back to 1776 (see Chapter 8). Trying to understand services productivity is particularly messy: That automated teller machine does not merely replicate the pin factory or behave like industrial scenarios. Finally, trying to quantify the particular contribution of information technology (IT) to productivity, and thus to the current unemployment scenario, proves particularly difficult. Nevertheless, the question is worth considering closely insofar as multiple shifts are coinciding, making job seeking, managing, investing, and policy formulation difficult, at best, in these challenging times.

Classic Productivity Definitions

At the most basic level, a nation's economic output is divided by the number of workers or the number of hours worked. This model is obviously rough and has two major implications. First, investment (whether in better machinery or elsewhere) does not necessarily map to hours worked. Second, unemployment should drive this measure of productivity up, all other things being equal, merely as a matter of shrinking the denominator in the fraction: Fewer workers producing the same level of output are intuitively more productive. Unemployment, however, is not free.

A more sophisticated metric is called multifactor productivity, or MFP. This indicator attempts to track how efficiently both labor and capital are being utilized. It is calculated as a residual, by looking at hours worked (or some variant thereof) and capital stock (summarizing a nation's balance sheet, as it were, to tally up the things that can produce other things of value for sale). Any rise in economic output not captured in labor or capital will be counted as improved productivity. The problem here is that measuring productive capital at any level of scale is extremely difficult.1

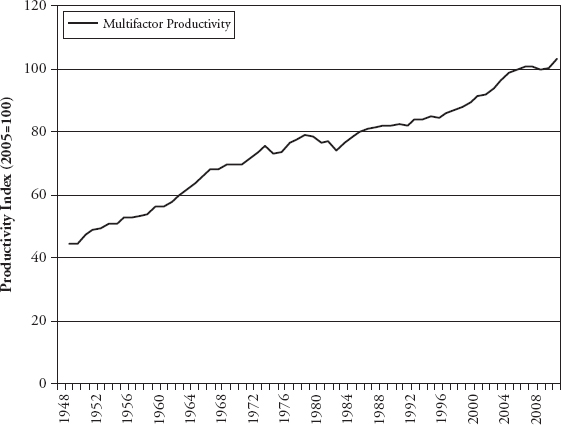

MFP, while hard to pin down, does have advantages. One strength is in its emphasis on innovation. In theory, if inventors and innovators are granted monopolies (through patents), their investment in new technologies can be recouped as competitors are prevented from copying the innovation.2 Skilled labor is an important ingredient in this process: Commercialization is much more difficult if the workforce cannot perform the necessary functions to bring new ideas and products to market. For one estimate of MFP for the United States, see Figure 14.1.

One relevant study took a deep dive into one manufacturing niche: valve assembly. The researchers found three mechanisms by which IT could influence productivity by changing business practices, not merely accelerating current-state activities:

We find that adoption of new IT-enhanced equipment (1) alters business strategies, moving valve manufacturers away from commodity production based on long production runs to customized production in smaller batches; (2) improves the efficiency of all stages of the production process with reductions in setup times supporting the change in business strategy; and (3) increases the skill requirements of workers while promoting the adoption of new human resource practices.3

FIGURE 14.1 Multifactor Productivity, 1948–2010

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Services Productivity

As The Economist points out, quoting Fast Company from 2004, ATMs did not displace bank tellers. Instead, the rise of self-service coincided with a broad expansion of bank functions and an aging (and growing) American population: Baby boomers started needing lots of car loans, and home mortgages, and tuition loans starting in about 1970, when the first boomers turned 25. People were required to deliver all those financial services:

1985: 60,000 ATMs; 485,000 bank tellers

2002: 352,000 ATMs; 527,000 bank tellers4

That a technology advance coincided with a shift in the banking market tells us little about productivity. Did ATMs, or word processors, or BlackBerries increase output per unit of input? Nobody knows: The output of a bank teller, or nurse, or college professor, is notoriously hard to measure. Even at the aggregate level, the measurement problem is significant. Is a bank's output merely the sum of its teller transactions? Maybe. Other economists argue that a bank should be measured by its balances of loans and deposits.5

A key concept in macroeconomics concerns intermediate goods: raw material purchases, work-in-process inventory, and the like. Very few services were included in these calculations, airplane tickets and telephone bills being exceptions. As of the early 1990s, for example, ad agencies and computer programming were not included.6 Thus, the problem is twofold: Services inputs to certain facets of the economy were not counted, and the output of systems integrators, such as Accenture or Tata Consulting Services, or advertising firms, such as Publicis or WPP, is intuitively very difficult to count in any consistent or meaningful manner.

Services Productivity and Information Technology

In the mid-1990s, a number of prominent economists pointed to roughly three decades of investment in computers along with the related software and services and asked for statistical evidence of IT's improvement of productivity, particularly in the period between 1974 and 1994, when overall productivity stagnated.

Those years coincided with the steep decline in manufacturing's contribution to the U.S. economy. Measuring the productivity of an individual office worker is difficult (as in a performance review), not to mention measuring the productivity of millions of such workers in the aggregate. Services are especially sensitive to labor inputs: Low student–faculty ratios are usually thought to represent quality teaching, not inefficiency. As the economist William Baumol noted, a string quintet still must be played by five musicians; there has been zero increase in productivity over the 300 years since the art form originated.7

The late 1990s were marked by the Internet stock market bubble, heavy investment by large firms in enterprise software packages, and business process “reengineering.” Alongside these developments, productivity spiked: Manufacturing sectors improved an average of 2.3% annually, but services did even better, at 2.6%. In hotels, however, the effect was less pronounced, possibly reflecting Baumol's “disease” in which high-quality service is associated with high labor content.8

Unfortunately, healthcare is another component in the services sector marked by low productivity growth and, until recently, relatively low innovation in the use of it. Measuring the productivity of such a vast, inefficiently organized, and intangibly measured sector is inherently difficult, so it will be hard to assess the impact of self-care, for example: People who research their back spasms on the Internet, try some exercises or heating pads, and avoid a trip to a physician. Such behavior should improve the productivity of the doctor's office, but only in theory can it be counted.

In a systematic review of the IT productivity paradox in the mid-1990s, economist Eric Brynjolfsson and his colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology investigated what they saw as four explanations for the apparent contradiction.9 Subsequent history suggests they are correct.

- Mismeasurement of outputs and inputs. Services industries (led by the financial sector) are among the heaviest users of IT, and services outputs are hard to measure. As we saw, productivity statistics in general are complex and not terribly robust.

- Lags due to learning and adjustment. This explanation has grown in influence in the past 15 years. To take one common example, the organizational adjustment to a $50 million to $100 million enterprise software deployment takes years, by which time many other factors will influence productivity: currency fluctuations, mergers or acquisitions, broad economic recessions, and so on.

- Redistribution and dissipation of profits. If a leading firm in a sector uses information effectively, it may steal market share from less effective competitors. The sector at large thus may not appear to gain in productivity. In addition, IT-maximizing firms might be using the technology investment for more effective forecasting, let's say, as opposed to using less labor in order fulfillment. The latter action would theoretically improve productivity. But if the wrong items were being produced relative to the market leader that more accurately sensed demand, profitability would improve at the leading firm even though productivity could go up at the laggard.

- Mismanagement of information and technology. In the early years of computing, paper processes were automated but the basic business design was left unchanged. In the 1990s, however, such companies as Wal-Mart, Dell, Amazon, and Google invented entirely new business processes and in some cases business models building on IT. The revenue per employee at Amazon ($960,000) or Google ($1.2 million) is far higher than at Harley-Davidson or Clorox (both are leanness leaders in their respective categories at about $650,000). “Mismanagement” sounds negative, but it is easy to see, as with every past technology shift, that managers take decades to internalize the capability of a new way of doing work before they can reinvent commerce to exploit the new tools.

Information Technology and Unemployment

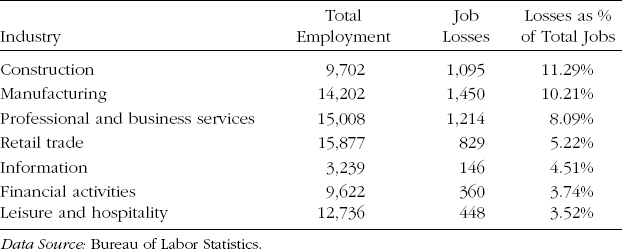

Are we in a situation that parallels farming, when tractors reduced the number of men and horses needed to work a given acreage? One way to look at the question involves job losses by industry. Using Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) numbers from 2009 (see Table 14.1), I compared the number of layoffs and business closings to the total employment in the sector.10 Not surprisingly, construction and manufacturing both lost in excess of 10% of total jobs. It's hard to point to IT as a prime factor in either case: The credit crisis and China, respectively, are much more likely explanations. Professional and business services, an extremely broad category, shrank by 8% in one year, which includes consultants among many other titles.

Another analysis can come from looking at jobs that never materialized. Using the BLS 10-year projections of job growth from 2000,11 the computer and information industry moved in a very different direction from what economists predicted. Applications programmers, for example, rather than being a growth category, actually grew only modestly. Desktop publishers shrank in numbers, possibly because of the rise of blogs and other Web- rather than paper-based formats. The population of customer service reps was projected to grow 32% in 10 years; the actual growth was about 10%, possibly reflecting a combination of offshoring and self-service, both phone and Web based. The need for retail salespeople was projected to grow by 12%, but the number stayed flat. Here is another example where IT, in the form of the Web and self-service, might play a role.

TABLE 14.1 2009 Layoffs and Business Closures as a Percentage of Total Sector Employment (All numbers in thousands)

Neither sales clerks nor customer service reps would constitute anything like a backbone of a vibrant middle class: Average annual wages for retail are about $25,000 while customer service reps do somewhat better, at nearly $33,000. The decline of middle-class jobs is a complex phenomenon: IT definitely automated away the payroll clerk, formerly a reliably middle-class position in many firms, to take one example. Auto industry union employment is shrinking, however, in large part because of foreign competition, not robotic armies displacing humans. That same competitive pressure has taken a toll on the thick management layer in Detroit as well, as the real estate market in the suburbs there can testify. Those brand managers were not made obsolete by computers.

Looking Ahead

President Obama gets the (almost) last word. In a town hall meeting in Illinois in mid-August 2011, he returned to the ATM theme:

One of the challenges in terms of rebuilding our economy is businesses have gotten so efficient that—when was the last time some-body went to a bank teller instead of using the ATM, or used a travel agent instead of just going online? A lot of jobs that used to be out there requiring people now have become automated.12

Have they really? The impact of IT and its concomitant automation on the unemployment rate is not at all clear. The effect is highly variable across different countries, for example. Looking domestically, travel agent was never a major job category: Even if such jobs were automated away as the number of agencies dropped by about two-thirds in the decade-plus after 1998,13 such numbers pale alongside construction, manufacturing, and, I would wager, computer programmers whose positions were offshored.

The unfortunate thing in the entire discussion, apart from people without jobs obviously, is the lack of political and popular understanding of both the sources of the unemployment and the necessary solutions. Merely saying “education” or “job retraining” defers rather than settles the debate about what is to be done in the face of the structural transformation we are living through. On that aspect, the president is assuredly correct: He has the terminology correct, but structural changes need to be addressed with fundamental rethinking of rules and behaviors rather than with sound bites and Band-Aids.

Notes

1. “Secret Sauce,” The Economist, November 12, 2009, www.economist.com/node/14844987.

2. Diego Comin, “Total Factor Productivity,” in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd ed., ed. Steven N. Durlauf and Lawrence E. Blume (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008). The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics Online, www.dictionaryofeconomics.com/article?id=pde2008_T000081.

3. Ann P. Bartel, Casey Ichniowski, and Kathryn Shaw, “How Does Information Technology Affect Productivity? Plant-Level Comparisons of Product Innovation, Process Improvement and Worker Skills,” Quarterly Journal of Economics (November 2007), www.nber.org/papers/w11773.

4. “Technology and Unemployment,” Economist.com blog post, June 15, 2011, www.economist.com/blogs/democracyinamerica/2011/06/technology-and-unemployment.

5. See Robert Inklaar and J. Christina Wang, “Real Output of Bank Services: What Counts Is What Banks Do, Not What They Own,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston working paper 11-1, February 2011, www.worldklems.net/conferences/worldklems2010_inklaar_wang.pdf.

6. Zvi Griliches, “Introduction to Griliches,” in Output Measurement in the Service Sectors (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992), p. 6.

7. David M. Herszenhorn, “For Ailing Health System a Diagnosis but no Cure,” New York Times, January 17, 2010, http://prescriptions.blogs.nytimes.com/2010/01/17/an-economist-who-sees-no-way-to-slow-rising-costs/.

8. Hal Varian, “Information Technology May Have Cured Low Service-Sector Productivity,” New York Times, February 12, 2004, http://people.ischool.berkeley.edu/~hal/people/hal/NYTimes/2004-02-12.html.

9. Erik Brynjolfsson, “The Productivity Paradox of Information Technology: Review and Assessment,” MIT Center for Coordination Science working paper, September 1992, http://ccs.mit.edu/papers/CCSWP130/ccswp130.html.

10. U.S. Census Bureau, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2011, tables 619 and 634, www.census.gov/compendia/statab/2011/2011edition.html.

11. “BLS Releases 2000–2010 Employment Projections,” press release, December 3, 2001, www.bls.gov/news.release/history/ecopro_12032001.txt.

12. “Obama and Travel Agents,” Economist.com blog post, August 21, 2011, www.economist.com/blogs/gulliver/2011/08/obama-and-travel-agents.

13. Ibid.