CHAPTER 19

News

News is a particular kind of business. Subject to some textbook examples of information economics, newspapers at their best also enrich communities, sustain democracies by speaking truth to power, and occasionally build family dynasties. The migration from paper to the Internet has proven particularly challenging, with implications for all three of those defining characteristics.

Compared to old-school stockbrokers disintermediated by $10 trades or travel agents put out of business by online booking and electronic tickets, newspapers have been undone in other ways. The power of the traditional newspaper was its bundling, in economic terms, along two axes. First, subscriptions bundle content by time: Readers pay for daily delivery of papers whether they get read or not, for the sake of convenience. In addition, a daily paper contains bundled content that a given reader ignores: people of a certain age will remember how many hundreds of pages of a 1990s Sunday New York Times were thrown away untouched.

The sheer material wastefulness of the resource-intensive physical distribution model might have been an indicator that alternatives could flourish. Incumbents, not surprisingly, included smart, informed editors and publishers, many of whom were pillars of their communities. That such highly esteemed men and women could preside over a wholesale dismantling of a century-old model in a few short years provides one reason why the transition of news is such a compelling story.

Incumbent Formula Pre-2005

Daily newspaper readership had been dented badly before, by the widespread introduction of radio, then television. After the decline in the 1940s, however, demographics helped stabilize the situation: As table 19.1 shows, circulation kept rising, on the strength of population growth, even as a smaller and smaller percentage of the population bought newspapers.

TABLE 19.1 U.S. Newspaper Circulation versus Population, 1900–2010

Figure 19.1 graphs the data from Table 19.1. Note that the drop-off in readership rates is hidden under population-driven circulation growth for several decades. Newspapers were underrepresented in the population in the aftermath of television especially, but the essentials of the business model did not change markedly.

That model was a classic two-sided platform. (See Chapter 5.) Newspapers aggregated audiences with advertising and the things advertising could buy: foreign bureaus, improved color and layout, faster presses, and so on. Advertising-side revenue, particularly classifieds, subsidized the subscriptions (by roughly 4:1), giving readers an attractive value proposition in that they received a product that cost more to produce than what they paid.

Customer Value Proposition

Newspapers could hire reporters and editors, subscribe to wire services, and print and distribute newspapers. Barriers to entry were high, and even in multipaper towns, one paper generally took the morning while the weaker one handled the less attractive afternoon business.* Monopoly dynamics applied: For depth (baseball box scores or stock tables), radio or television couldn't compete, and newspapers were unchallenged in some categories of news. For local matters, such as zoning or school boards, television typically found the tedium of committee meetings and report filings ill-suited for their 20 minutes at 6:00 and 11:00 p.m. From an advertiser standpoint, the infinite capacity for classified ad inventory meant that used cars, apartment listings, or job postings were much better suited to print than electronic media. This is, of course, a classic network externality: Every additional help-wanted ad, or open house, makes the platform more valuable to both advertisers (which gain strength in numbers relative to other channels) and to customers, who become more likely to solve their search needs with one-stop shopping.

FIGURE 19.1 U.S. Newspaper Readership, 1900–2010

Profit Formula

Time-based bundling, better known as subscriptions, helped match production to demand and generated less waste compared to more volatile newsstand sales. In cases where subscriptions were paid ahead of delivery, newspaper companies enjoyed steady revenue flows and better working capital: Ink and newsprint and reporters' salary and benefits were to some degree paid for before they were consumed.

The bundling of material into sections meant that every newspaper enjoyed the luxury of subsidies: Classified ads cost essentially nothing to produce but brought in handsome revenues, as did grocery store ads. Advertising in turn subsidized other efforts, such as foreign news bureaus, which could not afford to pay their own freight. Bundling meant that no person typically read everything every day, but every reader could find something of interest. As long as ad revenues were sufficient to maintain the editorial side of the house, profits were solid or even attractive.

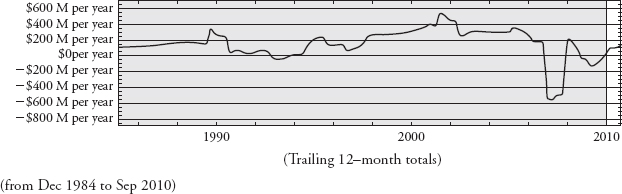

Note in Figure 19.2 that for the New York Times Company, profits were steady, with a dip during the early-1990s recession, from 1984 until 2006, during which year the company took an $814 million write-down related to its Boston Globe and Worcester Telegram properties.

Key Resources

Given a newspaper's status as a two-sided platform, running a newspaper required parallel sets of resources. In fact, an article of faith among practitioners was the integrity of the separation between editorial (reader-side customers) and advertising (commercial interests) functions. Ad sales, editorial-page positioning, and overall circulation numbers were required to keep advertisers happy; quality reporting, good pictures, the right mix of syndicated comics, and heavy ad inventory in key segments (such as apartment listings or job postings) attracted readers. The more readers, the more advertising revenue. The more advertising, the more reporters and columnists, the more color pages, and the more coverage: Ideally, these enhancements led to still more readership.

Thus, the required resources were extensive, which helped raise barriers to entry: reporters, editors, layout teams, pressmen, drivers, ad sales forces, human resource functionaries to deal with large staffs, and extensive billing and customer service operations. Capital investment in presses, syndication memberships, and delivery fleets (not to mention oil-related operating expenses for fuel and ink) made skilled financial management a requirement for long-term success.

FIGURE 19.2 New York Times Company Net Income, 1984–2010

Source: Wolfram Alpha LLC. 2011. input=” new york times company revenue” Wolfram | Alpha.

Key Processes

Not surprisingly, those key resources performed obvious functions: Reporters reported and wrote, editors edited, pressmen printed, drivers delivered, sales reps sold, accountants counted. Skillful and attuned editorial leadership could drive readership with good story selection, astute newswriting, and other effects of quality; the opposite could quickly alienate a paper from its community.

Business Model Disruption

If the music industry's problem was resisting the spread of free music via the Internet, the newspapers' problem was in part caused by giving too much value away for too long. In addition, the threats came from multiple directions, in such large numbers and in such diversity that a focused strategic response was essentially impossible: As early as 1998 one consultant aptly referred to the process as “termiting.” Surprisingly, a prominent newspaper industry report from 2009 preferred instead to blame a single villain.

Then the emergence of Google, an Internet search company that was launched without a business plan, soon blew up the content business into millions of “atomized” pieces, each piece disassociated at some level from its original context and creator. Like all the king's men, news enterprises were left to put the Humpty Dumpty of editorial and commercial content back together again, restore their original integrity, and finance the costly operation of being the trusted curator of news and transactions.1

This representation is somewhat disingenuous: “Financing the costly operations” of content creation and curation is still profitable. As the Princeton historian Paul Starr points out, the average newspaper operating margin in late 2008 was 11.5%.2 The problem, however, is that percentage represents roughly a 50% drop from only six years prior, and the decline appears to be deepening. Accordingly, investor confidence in the future of the business model is plummeting: Newspaper stocks have been battered through good times and bad since 2005 or so.

Long before Google News, however, many of the bundled facets of a newspaper were separated out by stand-alone Web businesses, each taking some segment of the readership and unbalancing the former cross-subsidies. Sports readers could go to the league sites (now with heavy video footage), television spinouts from Fox/ESPN/CNN+Sports Illustrated, fan-driven blogs and/or message board efforts, or any number of sites updating them on favorite cricket, soccer, or other international sports the metro dailies can barely cover, if at all. The local geographic monopoly was broken.

News is still primarily gathered by the usual suspects but commented on, linked to, and reaggregated by everyone from Google News, to bloggers, to ideology-driven destination sites. Daily A–Z stock charts aren't a particularly helpful way to watch the financial world, opening the door to broad distribution of previously professional-grade charting, archiving, and analytics; less professional message boards, blogs, and other mechanisms spread the wisdom (or lack thereof) of crowds.

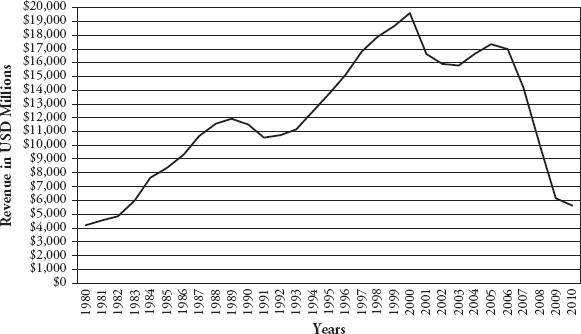

At the same time and in a similar manner, the papers' extremely profitable ads were hit hard by multiple competitors. (See Figure 19.3.) eBay then later Craigslist took over the realm of random objects, Monster and others (including the hiring firms directly) redefined the help-wanted field, and Edmunds and Cars.com along with eBay Motors improved on the car-buying experience by improving information availability and transparency. Match.com and eHarmony improved on the user experience and inventory levels of the personal ads, while real estate agents alone and in their trade association aggregated and augmented millions of property ads with photos, maps, and video walk-throughs. Online food-related sites proliferated, all better at providing meal solutions than the once-a-week recipe page that accompanied the newspaper grocery ads.

FIGURE 19.3 Classified Advertising Revenue, 1980–2010

Data Source: Business Analysis and Research, Newspaper Association of America, “Advertising Expenditures,” www.naa.org/Trends-and-Numbers/Advertising-Expenditures/Annual-All-Categories.aspx.

In the end, most any page of a 1990s-era newspaper was challenged by an online outlet. With the readership in decline, both ad and subscription revenue spiraled downward, and the splintered nature of the competition made coordinated response impossible. Newspapers are also hampered by their physical distribution model: News is old before readers even receive their papers, petroleum-intensive physical distribution is expensive, and from an ecological perspective, newsprint is anything but green. Indeed, U.S. newsprint consumption fell by 50% between 2001 and 2009.3 Because this figure is greater than the rate of subscriber loss, papers were getting smaller as well, indicating a steep decline in ad revenue.

In addition, the culture of “free” has affected news nearly as much as music, but far less so than books, for example. Some observers, including The Economist, have speculated that a Kindle or other reader might play a part in a revitalized news distribution business model. This makes sense: Books, newspapers, and magazines emerged as business opportunities following a technology disruption, so changing the technology implies change for both reading habits and business building.

Indeed, 2010 proved to be the year of the tablet following the rapid consumer adoption of the iPad. Large content companies such as Conde Nast, News Corporation, and Time Warner flocked to tablets, hoping to establish an early consumer pattern in which paying for news was a conditioned behavior. Before the device was released, industry insiders, hoping for such a state of affairs, called the iPad “the Jesus tablet.”4 Now that the category appears to be thriving, however, pricing, ergonomics, archives, the balance of still to video layouts, and many other aspects of the newspaper model remain works in progress, and no clear answer has yet emerged, profitable or not.

Looking Ahead

In parallel with the decline in newspaper readership, the advertising industry has been fundamentally challenged by targeted, interactive, and well-instrumented ads and all they imply. If tablets and other e-readers do reinvigorate the news business, this sector will need to move sure-footedly in parallel with the editorial business to regain much of the ground it has lost to Google in the past few years. In addition, while the movement away from traditional print models is highly visible, YouTube and the phenomenal rise of Internet video will also force a reshaping of television's economics. The ability of citizens armed with cameraphones to “report” on local events, as on CNN's iReports, further complicates the news business.

What If Digital News Is Inherently Unprofitable?

On the day that the Chicago Tribune broke the story of Illinois Governor Rod Blagojevich's arrest for allegedly peddling Barack Obama's Senate seat, the paper's parent company declared bankruptcy. The timing told a powerful story. In a time and in a world with so much up for grabs and such a pressing need for informed citizenries, the demise of the daily newsprint-driven business model raises critically important questions about accountability, about investment, and about the role of advertising.

Losing a newspaper is different from losing a travel agent or record store. Democracy is premised on public accountability, and a free, active press supports that objective, particularly through investigative journalism. A variety of efforts are under way to redefine newspaper reporting as a civic trust, potentially supported with foundation grants, National Public Radio-type donations, or a hybrid model. As Paul Starr put it,

If newspapers are no longer able to cross-subsidize public-service journalism and if the decentralized, non-market forms of collaboration [such as Wikipedia] cannot provide an adequate substitute, how is that work going to be paid for? The answer, insofar as there is one, is that we are going to need much more philanthropic support for journalism than we have ever had in the United States.5

Yale's David Swensen and Michael Schmidt made the same point in a New York Times editorial just weeks earlier:

[T]here is an option that might not only save newspapers but also make them stronger: Turn them into nonprofit, endowed institutions—like colleges and universities. Endowments would enhance newspapers' autonomy while shielding them from the economic forces that are now tearing them down.6

How big an endowment? A budget the size of the New York Times would cost $5 billion to endow. That's Warren Buffett/Bill Gates territory, unless Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg were to step up.

Notes

1. American Press Institute, Paid Content: Newspaper Economic Action Plan, May 2009, p. 7, www.niemanlab.org/pdfs/apireportmay09.pdf.

2. Paul Starr, “Goodbye to the Age of Newspapers (Hello to a New Era of Corruption),” New Republic, March 4, 2009, www.tnr.com/article/goodbye-the-age-newspapers-hello-new-era-corruption.

3. Michael Ducey, “Newsprint Demand, Production Continue Freefall,” March 29, 2010, www.newsandtech.com/news/article_cac1f0dc-3b57-11df-b071-001cc4c03286.html.

4. Kenneth Li and Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson, “Industry Awaiting ‘Jesus Tablet,’” FT, January 28, 2010, www.ft.com/cms/s/2/cd8e6ee6-0ba3-11df-9f03-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1gLKodEin.

5. Starr, “Goodbye to the Age of Newspapers.”

6. David Swensen and Michael Schmidt, “News You Can Endow,” New York Times, January 27, 2009, www.nytimes.com/2009/01/28/opinion/28swensen.html?pagewanted=all.

*As urban congestion worsened in the 1970s and after, getting the trucks full of papers to delivery points was much more difficult than the task of distributing newspapers at 5:00 A.M.