CHAPTER 21

The Importance of Frameworks, Policies, Procedures, and Controls

In this chapter you will learn:

• Common information security management frameworks

• Common policies and procedures

• Considerations in choosing controls

• How to verify and validate compliance

Innovation and best practices can be sown throughout an organization—but only when they fall on fertile ground.

—Marcus Buckingham

It is never a good idea to reinvent the wheel. It wastes time and you could end up with a worse wheel. This is particularly true in cybersecurity, where many great minds have spent years curating best practices and organizing them in useful ways. One of the byproducts of their efforts is the development of frameworks that provide structure to collections of these best practices. In this chapter, we’ll introduce some cybersecurity frameworks with which you should be familiar, and then we’ll delve into the policies, procedures, and controls that bring those frameworks to life in your organization. We close this last chapter with a brief discussion of the means by which you can verify that all this work is actually protecting your organization.

Security Frameworks

As you probably well know, security is not a one-size-fits-all proposition. Though there are certainly best practices, how we implement them ultimately depends on a variety of factors in our environments. Still, we need to have a way to conceptually frame the various issues we must consider as we protect our information systems. This is where security frameworks come in. The Oxford English Dictionary defines framework as a basic structure underlying a system, concept, or text. By extension, a cybersecurity framework can be defined as a structure on which we build cybersecurity systems. There is no shortage of them in cybersecurity, but, fortunately, you don’t have to remember them all.

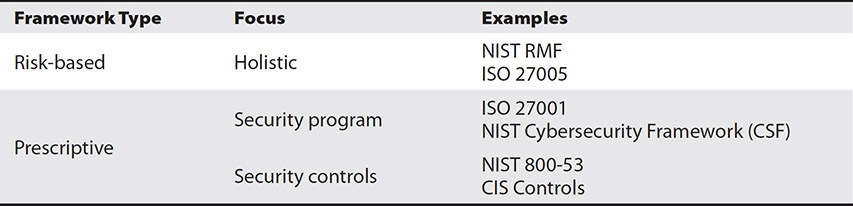

Generally speaking, there are two types of cybersecurity frameworks: those that are risk-based and those that aren’t. This second category is sometimes referred to as prescriptive security frameworks, because they consist of sets of requirements that must be implemented without an explicit relationship to risk management. Prescriptive frameworks, in turn, can be divided into those that are focused on overarching security programs and those that are focused on specific controls. Table 21-1 captures these distinctions and highlights some of the frameworks with which you should be familiar, not only for the CySA+ exam but in your daily job. We delve into these in the sections that follow.

Table 21-1 Types of Cybersecurity Frameworks

NIST

One of the most influential organizations in terms of cybersecurity standards and frameworks is the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST). It is the part of the US Department of Commerce, which is charged with promoting innovation and industrial competitiveness. As part of this mission, NIST develops and publishes standards and guidelines aimed at improving practices, including cybersecurity across a variety of sectors. Though it is certainly worth your time to familiarize yourself with the many NIST publications, you should be aware of three in particular as a CySA+ candidate: the Risk Management Framework (RMF) described in NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-37, “Risk Management Framework for Information Systems and Organizations: A System Life Cycle Approach for Security and Privacy”; the whitepaper “Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity” (the Cybersecurity Framework, or CSF); and NIST SP 800-53, “Recommended Security Controls for Federal Information Systems.”

Risk Management Framework

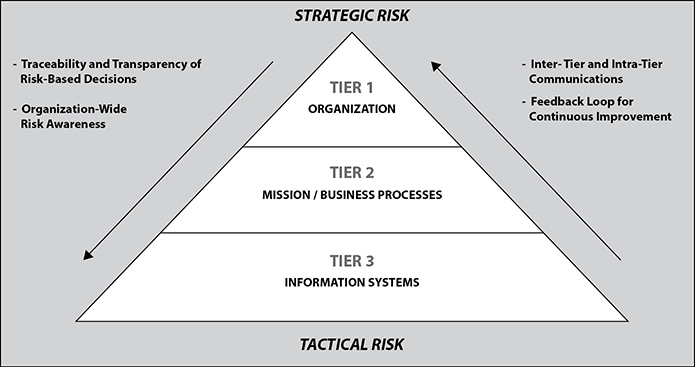

The NST RMF is defined in multiple publications. However, the foundational document for understanding the RMF is SP 800-39, “Managing Information Security Risk.” This publication defines three tiers to risk management, which are depicted in Figure 21-1:

Figure 21-1 Tiers of the organization-wide Risk Management Framework

• Organization tier This tier is concerned with risk to the business as a whole, which means it frames the rest of the conversation and sets important parameters such as the risk tolerance level. It focuses primarily on governance and program-related risk management.

• Mission/Business Processes tier This tier deals with the risk to the major functions of the organization, such as defining the criticality of the information flows between the organization and its partners or customers. It focuses more on cross-organizational process risk common to multiple business units.

• Information Systems tier This tier addresses risk from an information systems perspective. This is where you will likely spend most of your time, though you need to be aware of the higher two tiers.

The tiers described should highlight the first advantage of using a security framework: it enables you to use multiple layers of abstraction to describe issues at different levels. The lowest tier is the tactical world in which cybersecurity analysts spend most of their time. Those working in this tier provide information to the business tier that, in turn, provides inputs to the more strategic organization tier. Directives and constraints flow down, taking into account the inputs that went up the hierarchy.

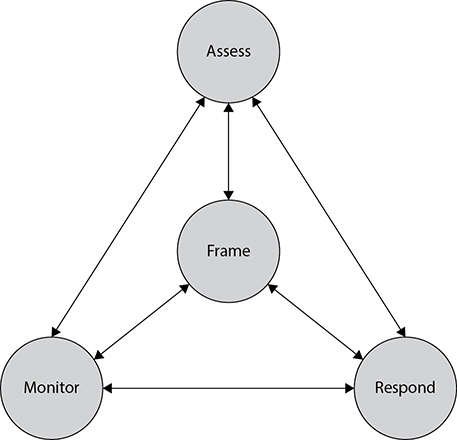

Another advantage of using a security framework is that it enables you to organize activities into related groupings. As shown in Figure 21-2, the RMF has four components that fully describe it at any one (or all) of the tiers described. The arrows denote communication flows between the functional groups, which are described here:

Figure 21-2 Components of the RMF

• Frame risk Risk framing defines the context within which all other risk activities take place. What are our assumptions and constraints? What are the organizational priorities? What is the risk tolerance of senior management?

• Assess risk Before we can take any action to mitigate risk, we have to assess it. This is perhaps the most critical aspect of the process, and one that we will discuss at length. If your risk assessment is spot-on, then the rest of the process becomes pretty straightforward.

• Respond to risk By now, we’ve done our homework. We know what we should, must, and cannot do (from the framing component), and we know what we’re up against in terms of threats, vulnerabilities, and attacks (from the assess component). Responding to the risk becomes a matter of matching our limited resources with our prioritized set of controls. Not only are we mitigating significant risk, but, more importantly, we can tell our bosses what risk we can’t do anything about because we’re out of resources.

• Monitor risk No matter how diligent we’ve been so far, we probably missed something. But even if we didn’t miss anything, the environment will likely change (perhaps a new threat source emerged or a new system brought new vulnerabilities). To stay one step ahead of the bad guys, we need to monitor the effectiveness of our controls continuously against the risks for which we designed them.

So what can you do with this? For starters, you can line up tasks with the appropriate framework components. For example, assessing risk at each of the tiers will be different. At the tactical level, you may consider technical vulnerabilities in your platforms. Assessing business-level risk, on the other hand, may involve dealing with threats that could prevent online orders from being processed. Finally, at the organizational level, the risks may be to brand image. The framework, then, gives you a way to look holistically at all the issues from the multiple different perspectives and in a structured way.

As we mentioned earlier, not every framework is explicitly concerned with risks. Let us now turn our attention to one of the most popular, prescriptive security program frameworks, which was also developed by the NIST.

Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity

On February 12, 2013, US President Barack Obama signed Executive Order 13636, calling for the development of a voluntary cybersecurity framework for organizations that are part of the critical infrastructure. The goal of this construct was for it to be flexible, repeatable, and cost-effective so that it could be prioritized for better alignment with business processes and goals. A year to the day later, NIST published the “Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity,” which was the result of a collaborative process with members of the government, industry, and academia. As of this writing, it is estimated that at least 52 percent of worldwide organizations have adopted some portion of or all of the framework. The framework is divided into three main components:

• Framework Core Consists of the various activities, outcomes, and references common to all organizations. These are broken down into five functions, 22 categories, and 98 subcategories.

• Implementation Tiers Categorize the degree of rigor and sophistication of cybersecurity practices, which can be Partial (tier 1), Risk Informed (tier 2), Repeatable (tier 3), or Adaptive (tier 4). The goal is not to force an organization to move to a higher tier, but rather to inform its decisions so that it can do so if it makes business sense.

• Framework Profile Describes the state of an organization with regard to the CSF categories and subcategories. It enables decision-makers to compare the “as-is” situation to one or more “to-be” possibilities, so that they can align cybersecurity and business priorities and processes in ways that make sense to that particular organization. An organization’s profile is tailorable based on the requirements of the industry segment within which it operates and the organization’s needs.

The core practices organize cybersecurity activities into five higher level functions with which you should be familiar. Everything we do can be aligned with one of these:

• Identify Understand your organization’s business context, resources, and risks.

• Protect Develop appropriate controls to mitigate risk in ways that make sense.

• Detect Discover in a timely manner anything that threatens your security.

• Respond Quickly contain the effects of anything that threatens your security.

• Recover Return to a secure state that enables business activities after an incident.

SP 800-53

One of the standards that NIST has been responsible for developing is SP 800-53, “Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations,” currently in its fourth revision. It outlines controls that agencies need to put into place to be compliant with the Federal Information Processing Standards (FIPS). It is worth noting that, although this publication is aimed at federal government organizations, many others have voluntarily adopted it to help them better secure their systems.

Basically, SP 800-53 provides specific guidance on how to select security controls. It prescribes a four-step process for applying controls:

1. Select the appropriate security control baselines.

2. Tailor the baselines.

3. Document the security control selection process.

4. Apply the controls.

The first step starts off with categorizing your information systems based on criticality and sensitivity of the information to be processed, stored, or transmitted by those systems. If this sounds familiar, that’s because we discussed these concepts in Chapter 19 when we covered data classification. SP 800-53 applies sensitivity and criticality to each security objective (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) to determine a system’s criticality. For example, suppose you have a customer relationship management (CRM) system. If its confidentiality were to be compromised, this would cause significant harm to your company, particularly if the information fell into the hands of your competitors. The system’s integrity and availability, on the other hand, would probably not be as critical to your business, so they would be classified as relatively low. The format for describing the security category (SC) of this CRM would be as follows:

SCCRM = {(confidentiality, high),(integrity, low),(availability, low)}

SP 800-53 uses three SCs: low, moderate, and high impact. A low-impact system is defined as an information system in which all three of the security objectives are low. A moderate-impact system is one in which at least one of the security objectives is moderate and no security objective is greater than moderate. Finally, a high-impact system is an information system in which at least one security objective is high. In our example, the SC of the CRM system would be high, because at least one objective (confidentiality) is rated high.

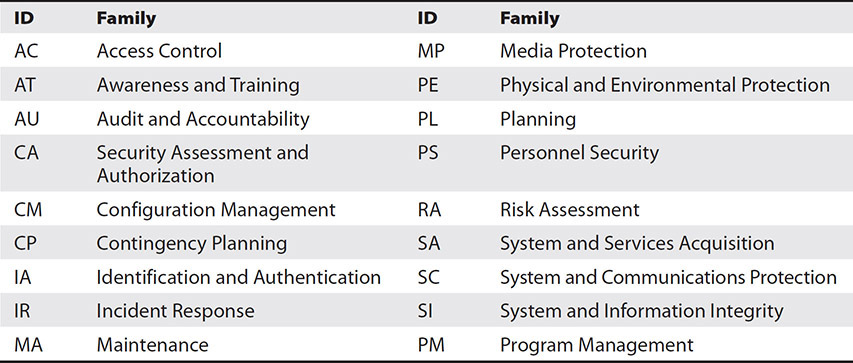

This exercise in categorizing your information systems is important because it enables you to prioritize your work. It also determines which of the 965 controls listed in SP 800-53 you need to apply to it. These controls are broken down into 18 families, as shown on Table 21-2.

Table 21-2 Security Control Identifiers and Family Names

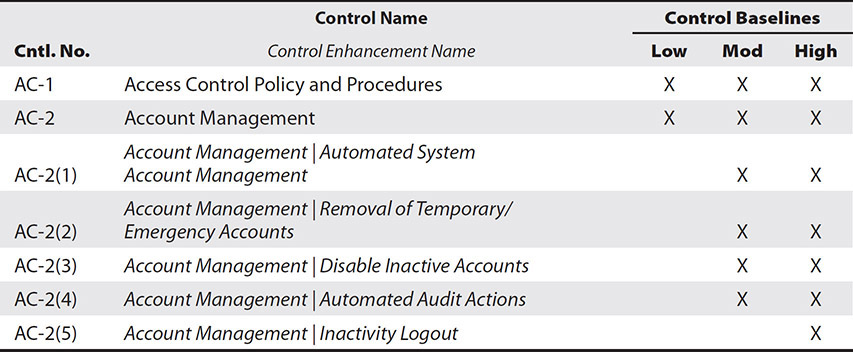

We can go through the entire catalog of controls and see which of them apply to our hypothetical CRM. In the interest of brevity, we will only look at the first two controls (AC-1 and AC-2) in the first family (Access Control, or AC). You can see in Table 21-3 how these controls apply to the different SCs. Since the CRM is SC high, both controls are required for it. You can also see that AC-2 has five control enhancements listed. (There are actually more, but we’re trying to keep this brief.)

Table 21-3 Sample Mapping of Security Controls to the Three Security Categories in SP 800-53

Let’s dive into the first control and see how we would use it. Appendix F of SP 800-53 is the “Security Control Catalog” that describes in detail what each control is. If we go to the description of the baseline AC-1 (Access Control Policy and Procedures) control, we’ll see that it requires that the organization do the following:

a. Develops, documents, and disseminates to [Assignment: organization-defined personnel or roles]:

1. An access control policy that addresses purpose, scope, roles, responsibilities, management commitment, coordination among organizational entities, and compliance; and

2. Procedures to facilitate the implementation of the access control policy and associated access controls; and

b. Reviews and updates the current:

1. Access control policy [Assignment: organization-defined frequency]; and

2. Access control procedures [Assignment: organization-defined frequency].

You noticed that there are assignments in square brackets in three of these requirements. These are parameters that enable an organization to tailor the baseline controls to its own unique conditions and needs. In this case, we get to specify who receives the policies and procedures pertaining to access control and how frequently these are reviewed.

The decisions we make in tailoring the controls must have sound rationales and should not be taken lightly. In the case of AC-1, how did we arrive at the list of staff/roles who would receive the policy, and on what factors did we base our decision to review the policy and procedures at a particular frequency? Sometimes, why we make decisions is almost as important as what decisions are made. Documenting the control selection process is important to support our assessment of the controls’ effectiveness, as well as for auditing purposes.

ISO/IEC 27000 Series

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) 27000 series serves as industry best practices for the management of security controls in a holistic manner within organizations around the world. The list of standards that makes up this series grows each year. Each standard has a specific focus (such as metrics, governance, auditing, and so on). The currently published standards (with more than a few omitted) include the following:

• ISO/IEC 27000 Overview and vocabulary

• ISO/IEC 27001 ISMS requirements

• ISO/IEC 27002 Code of practice for information security controls

• ISO/IEC 27003 ISMS implementation

• ISO/IEC 27004 ISMS measurement

• ISO/IEC 27005 Risk management

• ISO/IEC 27006 Certification body requirements

• ISO/IEC 27007 ISMS auditing

• ISO/IEC 27008 Guidance for auditors

• ISO/IEC 27011 Telecommunications organizations

• ISO/IEC 27014 Information security governance

• ISO/IEC 27015 Financial sector

• ISO/IEC 27031 Business continuity

• ISO/IEC 27032 Cybersecurity

• ISO/IEC 27033 Network security

• ISO/IEC 27034 Application security

• ISO/IEC 27035 Incident management

• ISO/IEC 27037 Digital evidence collection and preservation

• ISO/IEC 27799 Health organizations

ISO 27001

One of these ISO/IEC standards that is particularly relevant to our discussion is 27001. ISO/IEC 27001 applies to any organization, regardless of size, that wants to formalize its security activities through the creation of an information security management system (ISMS). This system documents the following, at a minimum:

• Who the stakeholders are and what are their expectations?

• What are the information security objectives?

• What are the risks to information systems?

• Which controls will be used to handle those risks?

• How are these controls to be implemented?

• How will the controls’ effectiveness be continuously monitored?

• What is the process to continuously improve the ISMS?

Similarly to how NIST SP 800-53 has 965 controls organized into 18 families, ISO/IEC 27001 has 114 controls organized into 14 domains. While the two standards are compatible with each other (SP 800-53 even has an appendix that maps its controls to these 14 domains), the NIST standard is focused on controls, and the ISO/IEC standard deals with the overarching program as well. The 14 domains in ISO/IEC 27001 are listed here:

• Information security policies

• Organization of information security

• Human resource security

• Asset management

• Access control

• Cryptography

• Physical and environmental security

• Operations security

• Communications security

• System acquisition, development, and maintenance

• Supplier relationships

• Information security incident management

• Information security aspects of business continuity management

• Compliance

Compare this to the families of controls shown in Table 21-2, and you should be able to see that ISO/IEC 27001 is concerned with much more than just the security controls. That is why, although it includes risk considerations as well as security controls, this framework is considered a prescriptive program–level framework.

ISO 27005

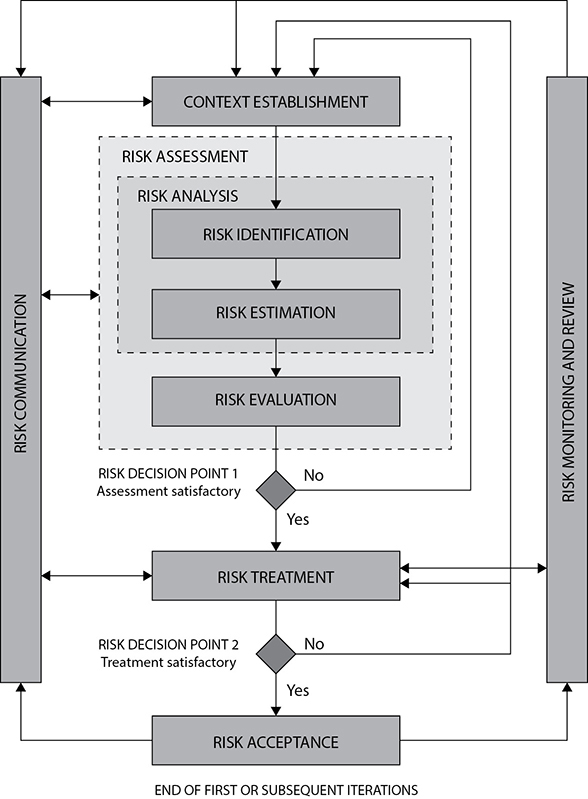

ISO/IEC 27005 is a risk-based framework, akin to the NIST RMF we discussed already. It provides guidelines for information security risk management in an organization but does not provide any specific method for information security risk management. In that regard, it is best used in conjunction with ISO/IEC 27001.

The risk management process defined by this standard is illustrated in Figure 21-3. It all hinges on establishing the context in which the risk exists. This is similar to the business impact analysis (BIA) we discussed in Chapter 20, but it adds new elements, such as evaluation criteria for risks as well as the organizational risk appetite. The risk assessment box in the middle of the figure should look familiar, since we also discussed this process (albeit with slightly different terms) in the last chapter. The risk treatment and risk acceptance steps are very similar to the “Respond to risk” functional grouping in the RMF, and the risk monitoring and review step is equivalent to the RMF’s “Monitor risk” group. Finally, risk communication is an essential component of any risk management methodology, since we cannot enlist the help of senior executives, partners, or other stakeholders if we cannot effectively convey our message to a variety of audiences.

Figure 21-3 The ISO/IEC 27005 Risk Management Process

As you can see, this framework doesn’t really introduce anything new to the risk conversation we’ve been having over the last two chapters; it just rearranges things a bit. Of course, despite these high-level similarities, the two risk-based frameworks we’ve discussed differ in a lot of the details. If you ever need to support your organization’s efforts to implement either of these, you probably want to get into these details.

Center for Internet Security Controls

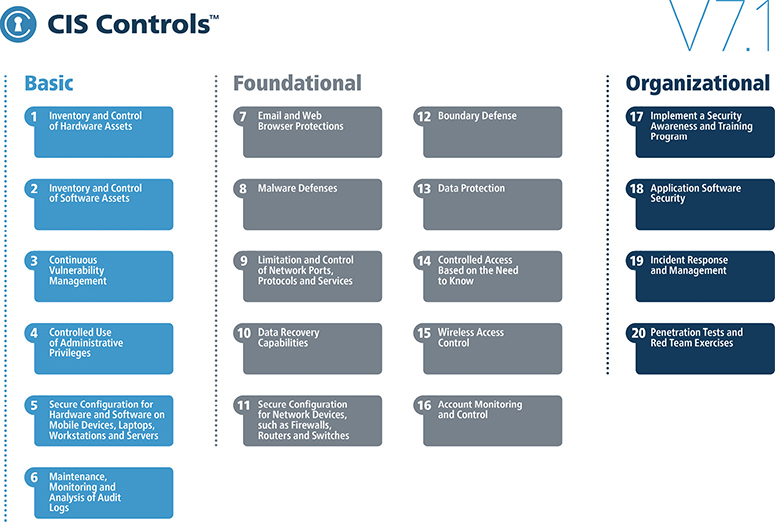

The Center for Internet Security (CIS) is a nonprofit organization that, among other things, maintains a list of 20 critical security controls designed to mitigate the threat of the majority of common cyber attacks. It is another example (together with NIST SP 800-53) of a prescriptive controls framework. The CIS controls, currently in version 7.1, are shown in Figure 21-4.

Figure 21-4 The CIS controls

Despite their use of the word “controls,” you should really think of these like the 18 families of controls in SP 800-53: as groupings. Under these 20, there are a total of 171 subcontrols that have similar granularity as those established by the NIST. For example, if we look into control 3 (Continuous Vulnerability Management), we can see the following seven subcontrols:

• 3.1 Utilize an up-to-date Security Content Automation Protocol (SCAP) compliant vulnerability scanning tool to automatically scan all systems on the network on a weekly or more frequent basis to identify all potential vulnerabilities on the organization’s systems.

• 3.2 Perform authenticated vulnerability scanning with agents running locally on each system or with remote scanners that are configured with elevated rights on the system being tested.

• 3.3 Use a dedicated account for authenticated vulnerability scans, which should not be used for any other administrative activities and should be tied to specific machines at specific IP addresses.

• 3.4 Deploy automated software update tools in order to ensure that the operating systems are running the most recent security updates provided by the software vendor.

• 3.5 Deploy automated software update tools in order to ensure that third-party software on all systems is running the most recent security updates provided by the software vendor.

• 3.6 Regularly compare the results from consecutive vulnerability scans to verify that vulnerabilities have been remediated in a timely manner.

• 3.7 Utilize a risk-rating process to prioritize the remediation of discovered vulnerabilities.

The CIS recognizes that not every organization will have the resources (or face the risks) necessary to implement all controls. For this reason, they are grouped into three categories, listed next. While every organization should strive for full implementation, this approach provides a way to address the most urgent requirements first and then grow over time.

• Basic These key controls should be implemented by every organization to achieve minimum essential security.

• Foundational These embody technical best practices to improve an organization’s security.

• Organizational These controls focus on people and processes to maintain and improve cybersecurity.

Policies and Procedures

The implementation of a security framework in an organization usually starts with a set of policies and procedures. For this effort to be successful, it must start at the top level and be useful and functional at every single level within the organization. Senior management needs to define the scope of security and identify and decide what must be protected and to what extent. Management must understand the regulations, laws, and liability issues it is responsible for complying with regarding security and ensure that the company as a whole fulfills its obligations. Senior management also must determine what is expected from employees and what the consequences of noncompliance will be. These decisions should be made by the individuals who will be held ultimately responsible if something goes wrong. But it is a common practice to bring in the expertise of the security officers to collaborate in ensuring that sufficient policies and controls are being implemented to achieve the goals being set and determined by senior management.

A security program contains all the pieces necessary to provide overall protection to an organization and lays out a long-term security strategy. A security program’s documentation should include security policies and procedures. The more detailed the rules are, the easier it is to know when one has been violated. However, overly detailed documentation and rules can prove to be more burdensome than helpful. The business type, its culture, and its goals must be evaluated to make sure the proper language is used when writing security documentation.

In the following sections, we discuss some of the foundational policies and procedures that any organization should have. The list is not all-inclusive, however, and simply mirrors the ones with which you must be familiar for the CySA+ exam.

Ethics and Codes of Conduct

Ethics are the moral principles that define what is right and wrong for a particular group of people, such as a corporation. Corporate ethics establish the “tone at the top,” which means that the executives need to ensure not only that their employees are acting ethically, but also that they themselves are following their own rules. The main goal is to ensure that the motto “Succeed by any means necessary” is not the spoken or unspoken culture of a work environment. Certain structures can be put in place to create a breeding ground for unethical behavior. If the CEO’s salary increases are based on stock prices, for example, then she may find ways to inflate stock prices artificially, which can directly hurt the investors and shareholders of the company. If managers can be promoted only based on the amount of sales they bring in, these numbers may be fudged and may not represent reality. If an employee can get a bonus only if a low budget is maintained, he might be willing to take shortcuts that could hurt company customer service or product development. Although ethics seem like things that float around in the ether and make us feel good when we talk about them, they have to be actually implemented in the real corporate world through proper business processes and management styles.

A code of conduct defines how a company’s employees should act on a day-to-day basis in accordance with their organization’s ethics. Most organizations have mission and vision statements; the code of conduct describes the manner in which employees are to conduct themselves in pursuit of the goals outlined in those statements. The code enables people to make the right decision when faced with an ethical dilemma. It also communicates to the outside world what the organization is all about. In some cases, legislation and other regulations actually require that organizations have codes of conduct formally published, in part because it is recognized that this reduces the risk of misbehaviors.

Acceptable Use Policy

The acceptable use policy (AUP) specifies what the organization considers an acceptable use of the information systems that are made available to the employees. Using a workplace computer to view pornography, send hate e-mail, and hack other computers, for example are almost always forbidden. On the other hand, many organizations allow their employees limited personal use of their networks, such as checking personal e-mail and surfing the Web during breaks. The AUP is a useful first line of defense, because it documents when each user was made aware of what is and is not acceptable use of computers (and other resources) at work. This makes it more difficult for a user to claim ignorance if he or she subsequently violates the AUP.

Password Policy

The password policy is perhaps the most visible of security policies, because every user will have to deal with its effects on a daily basis. A good password policy should motivate users to manage their passwords securely, describe to them how this should be accomplished, and prescribe the consequences of failing to comply. The three main elements in most password policies relate to generation, duration, and use.

When creating passwords, users should be informed of the requirements of an acceptable one. Commonly, these standards include some or all of the following:

• Minimum length (for example, eight characters or greater)

• Requirement for specific types of characters (such as uppercase, lowercase, numbers, and special characters)

• Prohibition against reuse (for example, cannot be any of the last four passwords)

• Minimum age (to prevent flipping in order to reuse an old password)

• Maximum age (for example, 90 days)

• Prohibition against certain words (such as user’s name or company name)

The policy should also cover the use of different passwords. For example, users should not use the same password for multiple systems, so that a compromise of one does not automatically lead to the compromise of all user accounts. Admittedly, this is a difficult provision to enforce, particularly when it comes to the reuse of passwords for personal and organizational use. Still, it may be worth including for educational purposes as well as to potentially mitigate some liability for the organization.

Data Ownership

Data ownership policies are typically combined with data classification policies because it is difficult to separate the two issues. The main reason is that the data is classified by the person who “owns” it. Data ownership policies establish the roles and responsibilities of data owners within the organization. The data owner (information owner) is usually a member of management who is in charge of a specific business unit and who is ultimately responsible for the protection and use of a specific subset of information. The data owner has due care responsibilities and thus will be held responsible for any negligent act that results in the corruption or disclosure of the data. Data owners decide the classification of the data for which they are responsible and alter classifications if business needs arise. These individuals are also responsible for ensuring that the necessary security controls are in place, defining security requirements per classification and backup requirements, approving any disclosure activities, ensuring that proper access rights are being used, and defining user-access criteria. The data owners approve access requests or may choose to delegate this function to business unit managers. Also, data owners will deal with security violations pertaining to the data they are responsible for protecting.

A key issue to address in a data ownership policy is who owns the personal data that an employee brings into an organizational information system. For example, if employees are allowed to check e-mail or social media sites from work, their personal data will traverse and be stored, albeit temporarily, on corporate information systems. Does it now belong to the company? Are there expectations of privacy? What about personal e-mail received by employees at their work accounts? These issues should be formally addressed in a data ownership policy.

Data Retention

No universal agreement states how long you should retain data that you own. Legal and regulatory requirements (where they exist) vary among countries and sectors. What is universal is the need to ensure that your organization has and follows a documented data retention policy. Doing otherwise is flirting with disaster, particularly when dealing with pending or ongoing litigation. It is not enough, of course, simply to have a policy; you must ensure that it is being followed and you must document this through regular audits.

A very straightforward and perhaps tempting approach would be to look at the lengthiest legal or regulatory retention requirement that affects your organization and then apply that timeframe to all your data retention. The problem with this, however, is that it will probably make your retained data set orders of magnitude larger than it needs to be. Not only does this impose additional storage costs, but it also makes it more difficult to comply with electronic discovery (e-discovery) orders. When you receive an e-discovery order from a court, you are typically required to produce a specific amount of data (usually pretty large) within a given timeframe (usually very short). Obviously, the more data you retain, the more difficult and expensive this process will be.

A better approach is to find the specific data sets that have mandated retention requirements and handle those accordingly. Everything else has a retention period that minimally satisfies the business requirements. You will find that different business units within medium and large organizations will probably have different retention requirements. For instance, you may want to keep data from your research and development (R&D) division for a much longer period than you keep data from the customer service division. R&D projects that are not particularly helpful today may be so at a later date, but audio recordings of customer service calls probably don’t have to hang around for a few years.

Work Product Retention

Work products are materials collected or prepared by an organization in anticipation of litigation. Just like conversations with legal counsel are protected under attorney–client privilege, work products enjoy a similar (but lesser) form of protection from discovery by the other party in the United States. For example, suppose your organization suffers a breach that likely exposes it to a lawsuit and you, as a cybersecurity analyst, are directed by your boss (ostensibly under some advice from legal counsel) to collect log files that could be used to defend the company in court. A plaintiff would not be entitled to those work products even though you were the one putting them together and you are not an attorney, nor did you directly communicate with one.

The issue becomes, how long can and should you retain those work products? You may (and should) have a data retention policy, but work products should be treated differently. There is no single best answer. The best thing to do is to consult with your legal counsel and establish what the right work product retention policy should be.

Account Management

A preferred technique of attackers is to become “normal” privileged users of the systems they’re compromising as soon as possible. They can accomplish this in at least three ways: compromise an existing privileged account, create a new privileged account, and elevate the privileges of a regular user account. The first approach can be mitigated through the use of strong authentication (for example, strong passwords and two-factor authentication) and by having administrators use privileged accounts only for specific tasks and only from jump boxes. The second and third approaches can be mitigated by paying close attention to the creation, modification, or misuse of user accounts. These controls all fall within the scope of an account management policy.

When new employees arrive, they should follow a well-defined process that is aimed at ensuring not only that they understand their duties and responsibilities, but also that they are assigned the required company assets and that these are properly configured, protected, and accounted for. Among these assets is a user account that grants them access to the information systems and authorization to create, read, modify, execute, or delete resources (for example, files) within it. The policy should dictate the default expiration date of accounts, the password policy (unless it is a separate document), and the information to which a user should have access. This last part becomes difficult, because the information needs of the users will typically vary over time.

Adding, removing, or modifying user permissions should be a carefully controlled and documented process. When is the new permission effective? Why is it needed? Who authorized it? Organizations that are mature in their security processes will have a change-control process in place to address user privileges. While many auditors will focus on who has administrative privileges in the organization, there are many custom sets of permissions that approach the level of an admin account. It is important, then, to have and test the processes by which elevated privileges are issued.

Another important practice in account management is the suspension of accounts that are no longer needed. Every large organization eventually stumbles across one or more accounts that belong to users who are no longer part of the organization. In some extreme cases, these users left the organization several months ago and had privileged accounts. The unfettered presence of these accounts on a network gives adversaries a powerful means to become a seemingly legitimate user, which makes our job of detecting and repulsing them that much more difficult.

Continuous Monitoring

In SP 800-137, NIST defines information security continuous monitoring as “maintaining ongoing awareness of information security, vulnerabilities, and threats to support organizational risk management decisions.” A continuous-monitoring procedure, therefore, would describe the process by which an organization collects and analyzes information in order to maintain awareness of threats, vulnerabilities, compliance, and the effectiveness of security controls. Obviously, this is a complex and very broadly scoped effort that requires coordination across multiple business units and tight coupling with the organization’s risk management processes.

When continuous monitoring reveals actionable intelligence (for example, a new threat or vulnerability), an established process should be in place to deal with this situation. The remediation plan describes the steps that an organization takes whenever its security posture worsens. This plan will likely have references to multiple procedures, some of which we discuss in this chapter. For example, if the issue is a newly discovered vulnerability in an application, the remediation plan would point the security team to the patching procedure. If, on the other hand, the change is due to an awareness that a security control is not as effective as it was thought to have been, the team would have to consider whether the control-testing procedure was effective or should be updated.

Control Types

Controls are put into place to reduce the organization’s risk, and they come in three main classes: managerial, technical (or logical), and operational (or administrative). Managerial controls are those that enable the overarching administration of the security of an organization. Examples of managerial controls are planning, risk assessment, security assessments, and systems acquisition processes. Technical controls are software or hardware components, as in firewalls, IDSs, encryption processes, and identification and authentication mechanisms. Finally, operational controls are those that are implemented by people (rather than by systems, as are technical controls). Examples of operational controls are incident response, personnel security, and security awareness.

These three control classes are used in NIST documents, but there is another class of control that we already discussed in Chapter 20. Physical security controls are tangible means of protecting facilities, devices, or people. They may not directly secure the data on a disk but they keep the disk from falling into the wrong hands. Examples of physical controls are fences, locks, cameras, and security guards.

Controls need to be put into place to provide defense-in-depth, which is the coordinated use of multiple security controls in a layered approach. A multilayered defense system minimizes the probability of successful penetration and compromise because an attacker would have to get through several different types of protection mechanisms before she gained access to the critical assets.

Technical controls that are commonly used to provide this type of layered approach include the following:

• Firewalls

• Intrusion detection systems

• Intrusion prevention systems

• Antimalware

• Access control

• Encryption

The types of controls that are actually implemented must map to the threats the company faces, and the number of layers that are included must map to the sensitivity of the asset. The rule of thumb is the more sensitive the asset, the more layers of protection must be in place.

So, the different classes of controls that can be used are managerial, technical, operational, and physical. But what functions do these controls actually perform? We need to understand the different functionality that each control type can provide us in our quest to secure our environments. By having a better understanding of the different control functions, you will be able to make more informed decisions about what controls will be best used in specific situations. The five different control functions are as follows:

• Preventative controls Intended to avoid an incident from occurring

• Detective controls Help identify an incident’s activities and potentially an intruder

• Corrective controls Repair or restore components or systems after an incident has occurred

• Deterrent controls Intended to discourage a potential attacker

• Compensating controls Controls that provide an alternative measure of control

When you’re implementing security for an environment, it is most productive to use a preventive model and then use detective and corrective mechanisms to help support this model. Basically, you want to stop any trouble before it starts, but you must be able to react quickly and combat trouble if it does find you. It is not feasible to prevent everything; therefore, what you cannot prevent, you should be able to detect quickly. That’s why preventive and detective controls should always be implemented together and should complement each other. To take this concept further, remember this: what you can’t prevent, you should be able to detect, and if you detect something, it means you weren’t able to prevent it, so therefore you should take corrective action to make sure it is indeed prevented the next time around.

One control functionality that some people struggle with is a compensating control, which we introduced in Chapter 20. Let’s look at some examples of compensating controls to best explain their function. If your company needed to implement strong physical security, you might suggest to management that they employ security guards. But after calculating all the costs of security guards, your company might decide to use a compensating (alternative) control that provides similar protection but is more affordable—as in a fence. In another example, let’s say you are a security administrator and you are in charge of maintaining the company’s firewalls. Management tells you that a certain protocol that you know is vulnerable to exploitation has to be allowed through the firewall for business reasons. The network needs to be protected by a compensating (alternative) control pertaining to this protocol, such as setting up a proxy server for that specific traffic type to ensure that it is properly inspected and controlled. So a compensating control is just an alternative control that provides similar protection as the original control but has to be used because it is more affordable or allows specifically required business functionality.

Audits and Assessments

Frameworks, policies, procedures, and controls are only useful if they are properly implemented. Otherwise, they can lead to a false sense of security, which can do more harm than good. How do we ensure they are properly implemented? We already discussed assessments in Chapter 20 in the context of risk management. Recall that an assessment is simply a process that gathers information and makes determinations based on it. We could, for example, conduct an assessment of our cybersecurity program to see if the controls we’ve implemented satisfy the requirements of SP 800-53. We could also hire a third party to do it, presumably in a more objective manner. Generally speaking, a cybersecurity assessment is any voluntary process that examines our programs (or a portion thereof) and determines whether we are meeting some sort of standard. In certain cases, however, this is not a voluntary decision.

An audit is a systematic inspection by an independent third party to determine whether the organization is in compliance with some set of external requirements. Think of it as a formal and rigorous assessment performed by an auditing firm that typically costs a bunch of money. Companies pay that money because either they want their stakeholders to know they are in compliance with some standard (e.g., “We are ISO 27001 certified”) or they are forced to do so by an industry or government regulation. Let’s explore each case in a bit more detail.

Standards Compliance

There are lots of reasons why companies would voluntarily put forth the effort to comply with external standards even if they are not required to do so. For starters, it can significantly reduce their risk and help establish due diligence. It may also be a precondition for sales to certain customers. For example, if you are a cloud service provider and want to sell your services to the US federal government, you must demonstrate that you are in compliance with the Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program (FedRAMP). Another reason is simply to differentiate yourself in a crowded market and show your potential customers that you care about protecting their information.

The most common standards compliance certifications, at least in the United States, are the ISO 27000 family (especially 27001) and FedRAMP. Both require significant investment both in preparing for an audit, and in supporting the auditors. For this reason, most organizations hire a third party to conduct one or more assessments before the auditors are brought in. This approach usually provides the best chance of getting successfully certified on the first audit.

Regulatory Compliance

Some organizations are subject to governmental statutes and regulations that may impose threshold requirements on securing information systems. Typically, being noncompliant with applicable regulations can lead to fines, penalties, and even criminal charges. While describing all aspects of regulatory compliance is beyond the scope of this book (and the CySA+ exam), you should be familiar with the more common laws and regulations, highlighted here:

• Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOX) This law, enacted in 2002 after the Enron and WorldCom financial crises, is intended to protect investors and the public against fraudulent and misleading activities by publicly traded companies. Its effect on information security controls is mostly in the area of integrity protections. SOX-regulated organizations have a higher bar set when it comes to ensuring that digital records are not improperly altered.

• Payment Card Industry Data Security Standard (PCI DSS) This industry standard applies to any organization that handles credit or debit card data. We already discussed it in Chapter 5, but it bears repeating that its main impact on security controls is focused on vulnerability scanning.

• The Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) This 1999 law applies to financial institutions and is intended to protect consumers’ personal financial information. Notably, it includes what is known as the Safeguards Rule, which requires financial institutions to maintain safeguards to protect the confidentiality and integrity of personal consumer information.

• Federal Information Security Management Act (FISMA) Enacted in 2002, FISMA applies to information systems belonging or operated by federal agencies or contractors working on their behalf. Among its key provisions are requirements on the minimum frequency of risk assessments, security awareness training, incident response, and continuity of operations.

• Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) This law mostly deals with improving privacy in the healthcare system, but it has important elements that impact information security policies and procedures. Significantly, it includes the Security and Privacy Rules, which place specific requirements on protecting the confidentiality, integrity, availability, and privacy of patient data.

Chapter Review

This chapter is packed with important information that will enable you to understand security frameworks, policies, procedures, and controls. Although you will probably see a handful of specific questions on these topics in the CySA+ exam, you will definitely see their influence not only on most exam questions, but in your work in a real-world organization. Though many of us prefer to spend our time fighting our cyber foes or improving our technical defenses, it is just as important to develop the formal documents that will ensure that the entire organization is pulling in the right direction. Without the appropriate policies and procedures in place, our efforts at securing our systems may very well ultimately be doomed to fail.

Questions

1. Which of the following is not a category for access controls and their implementation?

A. Managerial

B. Operational

C. Virtual

D. Logical

2. Which publication outlines various security controls for government agencies and information systems?

A. NIST SP 800-53

B. NIST SP 800-37

C. ISO/IEC 27001

D. ISO/IEC 27005

3. Which of the following publications describes a voluntary cybersecurity structure for organizations that are part of the critical infrastructure?

A. “Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity”

B. ISO/IEC 27005

C. ISO/IEC 27023

D. NIST SP 800-37

4. ISO/IEC 27001 describes which of the following?

A. The Risk Management Framework (RMF)

B. Information security management system (ISMS)

C. Work product retention (WPR) standards

D. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) standards

5. Which component of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework describes the degree of sophistication of cybersecurity practices?

A. Framework Core

B. Implementation Tiers

C. NIST SP 800-53 control categories

D. ISO/IEC 27001

6. Which are the key functions of the Framework Core of the NIST Cybersecurity Framework?

A. Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover

B. Identify, Process, Detect, Respond, Recover

C. Identify, Process, Detect, Relay, Recover

D. Identify, Protect, Detect, Relay, Recover

7. Which of the following would be least influential in developing a data retention policy?

A. Legal and regulatory requirements

B. Acceptable use

C. Business needs

D. E-discovery

8. Which of the following is not a good example of a preventative control?

A. Guard dogs

B. Policies and procedures

C. Audit logs

D. Biometrics

Answers

1. C. Virtual controls are not one of the categories of access controls, which are the mechanisms put in place to protect the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of systems. Access controls are categorized as managerial, operational, and technical (aka logical).

2. A. NIST SP 800-53, “Security and Privacy Controls for Federal Information Systems and Organizations,” aims to establish a unified information security framework for the federal government and related organizations.

3. A. The NIST “Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity” focuses on aligning cybersecurity activities with business processes and including cybersecurity risks as part of the organization’s risk management processes. The Cybersecurity Framework (CSF) consists of three parts: the Framework Core, the Framework Profile, and the Framework Implementation Tiers.

4. B. ISO/IEC 27001 provides best practice recommendations on information security management systems (ISMS).

5. B. CSF Implementation Tiers categorize the degree of rigor and sophistication of cybersecurity practices, which can be Partial (tier 1), Risk Informed (tier 2), Repeatable (tier 3), or Adaptive (tier 4).

6. A. The Framework Core consists of five functions that can provide a high-level view of an organization’s management of cybersecurity risk: Identify, Protect, Detect, Respond, Recover.

7. B. Although acceptable use violations may influence a data retention policy to some extent, the other three options must be considered when developing it.

8. C. Audit logs are a good example of a detective control, in that they help us detect when a security incident has occurred. However, unless a threat actor is somehow aware of and discouraged by our logging policy, it is extremely unlikely that this would be a good preventive control.