NON-TRUST STRUCTURES

‘Each generation has a duty to commit to a contract between the past, the present and the future.’

Sir James Goldsmith, financier

There is a range of non-trust structures that might be used either in addition to or instead of a trust to hold and control wealth. In this chapter I explain the main non-trust structures,

Family investment companies

We looked at the use of a family investment company in Chapter 16 as a means of holding investments for the wider family and to obtain administration, cost and taxation benefits. However, an FIC also offers significant wealth succession and inheritance tax planning opportunities.

Capital structure

There is total flexibility in how the FIC can be structured in terms of the split of equity and loan capital. For example, you could subscribe a nominal £100 equity for 100 shares and have the main capital as an on-demand loan. If any of the FIC shares are to be gifted or not held jointly by a married couple, it will be necessary for you to receive a commercial rate of interest to avoid IHT issues.

As the shares would, in this scenario, be worth only £100 on day one, some or all of these can be gifted outright to other family members and/or transferred into a discretionary trust (or a number of discretionary trusts). This would enable the growth in the value of the shares to be captured by the other family members and/or the family trust(s) and therefore be outside your estate for IHT purposes. You could defer the decision on gifting any of the shares to a later date, but the longer you leave it, the more valuable the shares may become as the investment portfolio increases in value and any loan is repaid.

The benefit of funding the company with a significant loan is that you can receive loan repayments as you need them, without incurring tax that would otherwise arise on the payment of dividends or the disposal of shares to other shareholders or at wind-up of the company. It makes sense, therefore, to fund the company with a loan to the extent required by your likely lifestyle needs. Lifetime cashflow forecasting software, using reasonable planning assumptions, can be helpful in this regard.

Share structure

An FIC can have several classes of share, with different rights, which provides a number of interesting planning opportunities. For example, there could be A, B, C and D shares. While all shares would rank equally for the same treatment (pari passu) on the winding up of the company, only the A shares would have voting rights on all matters. In addition, the A shareholders would usually be directors of the company and so be able to control the investment and dividend-distribution strategy.

If all the voting shares are owned by the same person (for these purposes a married couple or civil partnership are considered one person), then for tax purposes their value is aggregated because the owner controls the voting rights. If, however, any of the non-voting rights were gifted to another family member and/or a trust, the A shares would be treated as being worth a premium to their actual cash value and the value of the gifted shares would be valued at less than their cash value due to the lack of voting rights. If, at a later date, the owners of the B, C or D shares received the A shares, perhaps via the A shareholder’s will after their death, the B, C and D shareholders’ shares would be subject to an immediate uplift in value due to acquiring the voting rights attaching to them.

Share valuation is a specialist area, but where the capital structure is relatively simple, the underlying asset of the company is a quoted, liquid investment portfolio and voting rights are concentrated in one class of shares owned by one shareholder, ascertaining a value should be less problematic. If some of the non-voting shares are gifted to a discretionary trust, this will trigger a chargeable lifetime transfer which means that HMRC would have to consider the values of all the share classes for inheritance tax. It would not have to do this if the gifts were made only to individuals and were potentially exempt transfers.

The FIC in action

It is perhaps easier to understand the key benefits of an FIC by looking at an example. What follows is just one example of how an FIC could be structured; there are numerous permutations possible.

Mike and Jackie are in their late 50s and they have £4 million of cash arising from the sale of a property, which they wish to invest in a diversified investment portfolio for the benefit of themselves and their wider family. Mike and Jackie both receive pension, rental and savings income, which utilises their personal allowances and basic-rate income tax bands. They have two children, Ben aged 32 and Matilda aged 29, who are both married with children, but they might have more in the future.

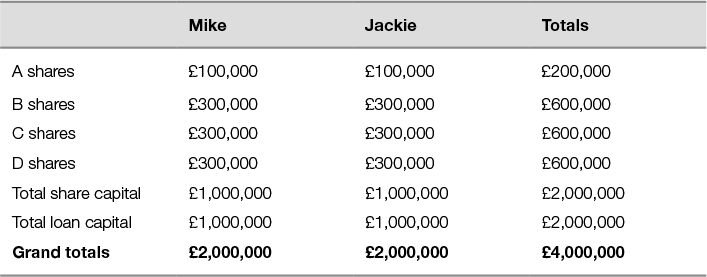

Mike and Jackie decide to create an FIC by subscribing £2 million of cash into four classes of share – A, B, C and D – of which only the A shares have voting rights, and appoint themselves as controlling directors. Mike and Jackie also make an on-demand loan to the FIC of £2 million and charge 4% p.a. interest (this being current market average for a mortgage). The exact allocation of capital is shown in Table 22.1.

Table 22.1 Capital structure of FIC

The FIC therefore holds £4 million of cash, which Mike and Jackie decide, as the controlling directors and sole shareholders, to invest in a diversified and fully liquid investment portfolio, of which 70% is allocated to equities and 30% to bonds via investment funds.

Mike and Jackie decide to retain the A shares but to gift the B shares to Ben, the C shares to Matilda and the D shares to a discretionary trust that includes Ben, Matilda and their current (and any future) grandchildren as potential beneficiaries. Mike and Jackie are also trustees of the trust.

The gifts of shares to Ben and Matilda will be treated as potentially exempt transfers and the gift to the discretionary trust treated as a chargeable lifetime transfer. On a practical note, the gift to the trust is made a day before the other gifts as this will minimise any inheritance tax that might become due if Mike and Jackie die before seven years have elapsed.

Value of gifts

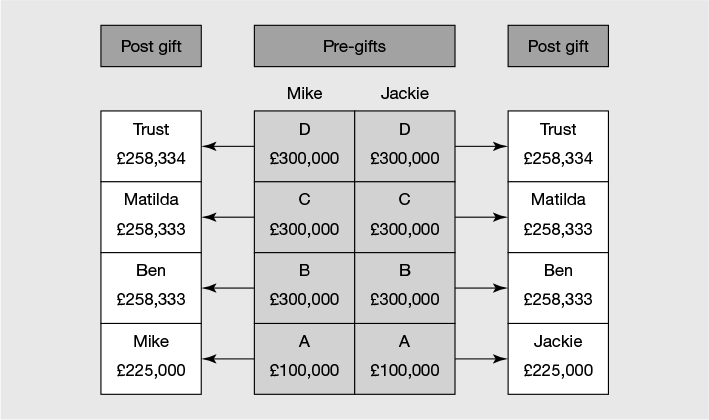

Because the retention of the A shares means that Mike and Jackie can control the company, and therefore the value attributed to the other shares, the A shares will be deemed to have a value for IHT purposes that is more than the appropriate percentage of the company’s net assets, i.e. the underlying portfolio. On the assumption (purely for illustrative purposes) that each of Mike’s and Jackie’s retained A shares would be worth, say, £225,000 rather than their respective £100,000 basic value, the total value of the other shares gifted for inheritance tax purposes would be £775,000, rather than their nominal value of £900,000 as set out in Figure 22.1.

Figure 22.1 FIC shares – inheritence tax values

Extracting value

Mike and Jackie don’t need to access their loan immediately, but the intention is to take ad hoc repayments to help meet their living costs in a few years’ time when they stop their part-time consultancy business. In the meantime, Mike and Jackie receive annual interest on the loan of 4% (£40,000 p.a. each) on the basis that it is fully secured against the company’s assets and repayable on demand. It would take 20 years for the loan to be repaid if repayments were taken at the rate of £100,000 per annum. As the loan reduces, so will the taxable interest that Mike and Jackie receive each year.

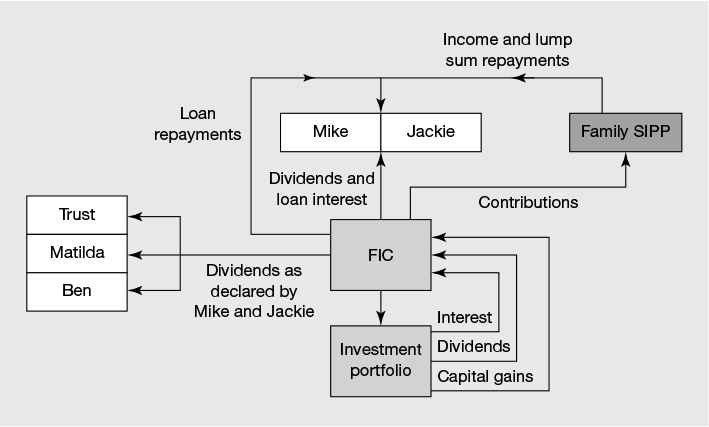

As controlling directors Mike and Jackie oversee the management of the company, including the investment strategy, in return for an annual pension contribution to their family self-invested pension (see Chapter 17 on family SIPP or SSAS) of £25,000. This avoids income tax and National Insurance and some or all of the contribution may be deductible for corporation tax purposes, while also avoiding IHT rules relating to reservation of benefit on gifts. Investment governance work, including the creation and updating of a formal investment policy statement (IPS) and the establishment and management of the investment portfolio, can be delegated to a wealth management firm. Figure 22.2 illustrates how Mike and Jackie and their family can take benefits from the FIC structure.

Figure 22.2 Extracting value from the FIC

The end result

By holding their investment portfolio via the FIC, Mike and Jackie have achieved the following estate planning outcomes:

- They retain access to the £2 million of capital loaned to the company and may take repayments as they need and investment conditions allow, without incurring personal taxation.

- They will receive reasonable taxable interest on the outstanding loan balance each year.

- They retain total control over the company, including the payment of any dividends.

- They could receive tax-free payments into their family SIPP.

- They have started the clock ticking on gifts worth circa £1.5 million and as long as they survive for seven years, these will fall out of account for IHT purposes.

- The value held by the discretionary trust and any future growth is sheltered from ‘hostile creditors’ and available for any of the wider family, including by granting loans.

- Although the value of the shares gifted to Ben and Matilda is lower than the face value, these would increase if Ben and Matilda received their parents’ A shares upon Mike and Jackie’s eventual demise. Although capital gains tax will be higher as a result, inheritance tax (which is charged at a higher rate than capital gains) should be lower as a result.

- They retain flexibility to invest in other asset classes in the future.

The use of FICs is a complex area and most suited to large-value estates that have already made maximum use of discretionary trusts. Expert advice should be sought from a legal and tax adviser who is familiar with this area.

Family limited partnerships

Family limited partnerships (FLPs) have been around in various forms for many years but have become more popular since the changes to trust rules in 2006. FLPs offer a structure that enables a family to bring together assets under common management, oversight and control of, say, the parents, but to obtain IHT and other benefits. An FLP is owned by its members, with designated members responsible for the governance and compliance matters. Usually the designated or controlling member will be either a general partner or a limited company.

Operation of the FLP is governed by the FLP agreement, which states how revenue profits/losses and capital gains/losses are to be treated. Because an FLP is transparent for tax purposes, income profits/losses and capital gains/losses arising each trading period will be taxed on each individual member, in proportion to their share as agreed in the FLP agreement. It is possible to vary how they will be allocated to different members from year to year. Capital contributions and capital profits can be the same as or different from each member’s income profits.

An FLP can be useful where there are assets, such as property, that have unrealised capital gains and are to be introduced as a member’s capital contribution, where profits need to be attributed differently to each member from year to year. In this respect an FLP is potentially more flexible than an FIC. However, if the FLP is a UK-constituted entity that establishes an investment portfolio, it will potentially be classed as an unregulated collective investment scheme and as such the FLP would need to be authorised and regulated by the UK Financial Conduct Authority. There are two ways to avoid the regulatory burden and expense associated with this obligation. First, the FLP could be established outside the UK, e.g. Jersey, or, second, the management of the investment portfolio could be delegated to a suitably authorised and regulated investment manager.

The use of FLPs is a complex area and most suited to large-value estates that have already made maximum use of discretionary trusts. Expert advice should be sought from a legal and tax adviser who is familiar with this area.

Inheritance tax portfolio services

Business property relief is a tax relief provided by the UK government as an incentive for investing in specific types of trading companies. It was introduced by the government in 1976 and has since been extended to investments in certain types of unquoted companies to encourage investment into this area.

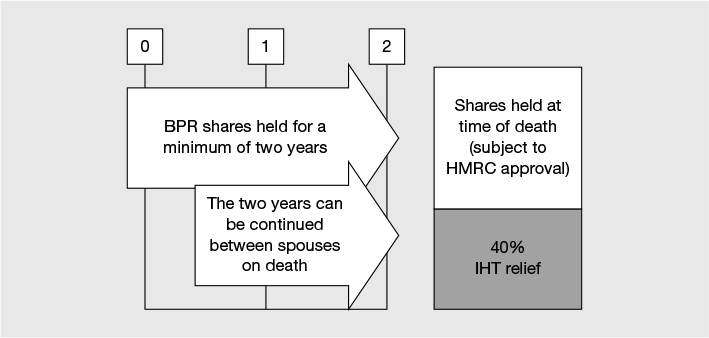

Once assets qualifying for BPR (this also applies to the assets that qualify for agricultural property relief) have been held for two years, they are exempt from IHT (provided that they are still held at the time of death). In the event of your death within two years, BPR assets would be subject to IHT.

However, if the asset is transferred to your spouse or civil partner upon death, it would be treated as if they had held it from outset and they would need to survive for only the remainder of that two-year period for it to be exempt from IHT (i.e. the first death does not restart the two-year clock – see Figure 22.3). In this situation your spouse or civil partner would still retain full control and access to the capital.

It is possible to obtain immediate IHT exemption from investment into a BPR-qualifying asset if the amount invested is equal to, or less than, the proceeds of an asset (possibly a family business) that previously qualified for BPR and that was disposed of within the past three years.

Figure 22.3 Inheritance tax relief in two years

Source: Bloomsbury Wealth Management.

A key benefit of holding an asset that qualifies for BPR is that it allows you to retain control of and access to it, meaning that you have flexibility should your circumstances change. The challenge is finding a BPR-qualifying asset that provides sufficient liquidity, capital security and investment return to make it attractive. There is clearly no benefit in saving 40% IHT if you’ve lost 50% of the value of your investment.

If you are at the stage in your life where investing into a new business is not appealing or you have neither the time nor the inclination to find a suitable BPR-qualifying business investment, there are well-tested solutions that can offer the benefits of BPR, while limiting the possible downsides.

The new breed of BPR investment

Over the past decade a number of investment solutions have been developed that give access to unquoted companies that qualify for BPR but that address the downsides of illiquidity and potential loss of capital usually associated with such investments. What follows is a description of how a typical (market-leading) BPR investment solution works.

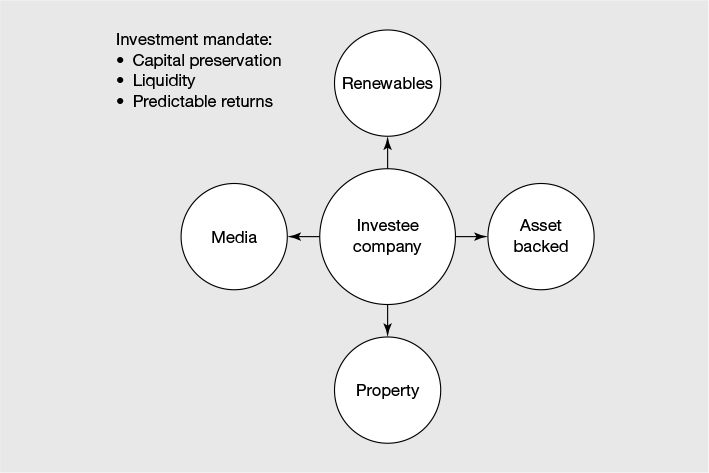

You invest your money into an unquoted company, which deploys its money into a number of BPR-qualifying trades, which are managed and controlled by the BPR scheme provider’s staff on behalf of you and the other investors. The only shareholders in these companies are the BPR scheme investors and their shareholdings are the only source of capital. The BPR scheme provider is, therefore, able to run these companies in a way that is best aligned with the interests of its investors. In particular, it can ensure that the companies only enter into transactions where it is able to mitigate the risks and maintain BPR treatment.

The types of trades in which the underlying companies engage are very carefully selected on the basis that they:

- are highly cash-generative and capital invested is continually returned to the wholly owned trading companies

- have minimum risk of capital loss due to trading activity and risk mitigation undertaken

- meet the qualifying criteria for BPR treatment

- can be closely monitored by the BPR provider.

See Figure 22.4.

Figure 22.4 Business property relief qualifying investments

Source: Octopus Investments.

Underlying investments

Examples of typical investee companies’ trades are as follows.

Property developer bridging finance

Typically, a developer needs to raise a loan against one property to enable them to fund development activity on another property. Traditional banks have become reluctant to lend, so this presents an opportunity for the BPR business to provide bridging finance, at a very good margin, secured by a first charge on the property. Usually the borrower will refinance the loan after 6–9 months, thus ensuring that the company is continually turning over cash. If the borrower does not repay the loan at the agreed time, the lender can sell the property. Since loans are usually less than 60% of the property value, anything short of a large fall in value or depressed sale value will not impede the ability to be repaid. The borrower will not want to lose their equity, so they are heavily incentivised to avoid foreclosure.

New car financing

Typically, finance of a new car is based on 100% of the purchase price, less a small deposit. However, a much lower-risk way of providing vehicles funding is to finance only the trade-in value of a new car, together with extremely strict underwriting of borrowers. This means that, in the event of default by the borrower, the car can be repossessed and sold at auction to recover the outstanding amount. With a low default rate and high asset cover on each loan, this is a very profitable business, which has been through three recessions and three stock market crashes.

Media

Providing financing of film and television production can be low risk when it is secured against pre-sold exploitation rights and/or government-backed tax credits, on a project-by-project basis. The typical media financing transaction lasts for between 6 and 18 months, although sometimes it can be longer, and this helps to maintain liquidity within the trading portfolio.

Solar energy

Financing commercial solar energy installations, which are underpinned by long-term government subsidies, provides strong cashflow at quite low risk, with the equipment protected against damage through insurance. Sometimes additional security is taken by way of a legal charge against the land or property on which the solar equipment is installed.

Expected return

Each of the underlying trades is highly profitable and generates continual cashflow. The BPR investment provider manages the trades and cashflow with the aim of preserving the value of investors’ capital (in nominal terms) and providing a return of 3% per annum compound (equivalent to 5% per annum for a 40% rate taxpayer) on the amount invested (after deducting initial and ongoing charges).

Although the underlying trades generate significantly more return than 3% p.a. compound, your return is unlikely to exceed 3% p.a. as the excess represents the BPR investment provider’s margin (after costs borne in running the underlying company’s business and paying corporation tax). Not benefiting from this excess return is the price that investors have to pay for the BPR provider’s oversight, minimising of downside loss and obtaining BPR treatment on the holding.

Some of the BPR investment providers are so confident that they can preserve investors’ capital and achieve, say, 3% annual growth that they choose to defer the payment of their annual management charges and will take them only at the time investors exit the BPR investment (or transfer the holding to a trust) and then only if the targeted annual return has been achieved after the deduction of the management fee. The company valuation is determined by reference to the principal amount invested plus whatever the target return is (typically 3% p.a.) compound, with ongoing oversight and advice from a major accountancy firm.

Access and liquidity

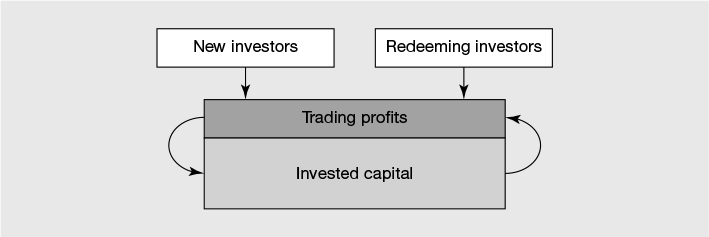

Although the BPR investment should not be operated like a bank account, investors can access their investment at any time. The minimum amount for a capital withdrawal is £1,000 and in the normal course of events withdrawals will be paid within a week or so, although under certain circumstances withdrawals may take up to 12 weeks. Because the leading BPR investment providers take in more cash from new investors than they pay out to exiting investors, withdrawals are facilitated by the provider transferring redeeming investors’ shares to new investors (see Figure 22.5).

If there were more sellers than buyers (which has not happened to date with the largest providers), the BPR company would buy back shares using retained cash. In the event of major legislative changes, such as the removal of BPR by the government and where liquidity within the company is insufficient to facilitate a share buyback, the process could take much longer. For example, if every investor wanted their money back at once, most BPR investment providers estimate that about 50% could be provided within 6–12 months and the balance within 24 months.

Figure 22.5 Managing liquidity

Source: Bloomsbury Wealth Management.

Taxation

Growth on the investment would be taxed only when investors withdraw money from the scheme. The investment return will normally be taxed as a capital gain when the redemption is a sale of shares to other investors (handled by the BPR company), but it will be subject to income tax (like a dividend) if, in order to achieve that withdrawal, the BPR company itself has to purchase the outgoing investor’s shares. It is only the growth that is taxed in either circumstance, not the amount withdrawn.

Individuals are entitled to an annual CGT exemption limit (£11,000 for the 2014/15 tax year). If they are not utilising their annual CGT exemption and the ‘gain’ on any withdrawal falls within this limit, there is no requirement to declare this or complete a tax return. If the amount of the ‘gain’ is greater than this annual exemption, CGT is payable on the excess at up to 28%. In the event of the investor’s death, there should be no liability to CGT on their investment.

A BPR investment solution is not a panacea and is unlikely to suit all individuals. However, if IHT is a concern (you have more years behind you than in front of you), you want to avoid the expense and complications of trusts and retaining control and access is important, it can be a useful planning tool as part of your overall wealth plan.

However, there are circumstances where it is not possible to obtain BPR. This might be because either you don’t have BPR-qualifying assets or don’t want to invest in the available BPR-qualifying investment arrangements. It may be the case that, whether or not you are prepared to invest in a BPR-qualifying investment, you might not be confident that you will survive the necessary two years for it to be exempt from IHT. This is where the next solution might be useful.

The discounted value arrangement

Until a few years ago there were a number of so-called ‘death bed’ planning arrangements which used a specially modified excluded property trust to remove value from an individual’s estate immediately. Such planning was popular with people who were in very poor health and who wanted to avoid 40% of their estate disappearing in IHT upon their eventual demise.

Immediate IHT reduction

Help is at hand, however, for those with a short life expectancy but who want to secure an immediate and sizeable reduction in their IHT exposure while also retaining some access to their capital. A discounted value arrangement (DVA) is an offshore investment bond which has special policy conditions that have the effect of immediately reducing its value for IHT purposes. No trusts or other complicated legal structures are involved and the investor does not need medical assessment.

An individual invests cash into a special offshore bond, of which they are deemed to be the legal owner. As well as the investor being the life assured, they appoint several other younger individuals from their family (although it could be anyone) as lives assured. The younger these people are, the better the planning (more of which later).

The policy conditions are such that the bond has no surrender value during the original policyholder’s lifetime, but they retain the right to take an annual withdrawal of up to 10% of the original investment, with any unused withdrawals being available to carry forward to future years. On the death of the original policyholder, the policy does not at this stage come to an end due to the existence of the other lives assured. However, the annual withdrawal right reduces to either 1%, 2% or 3% per annum and the surrender value remains suppressed.

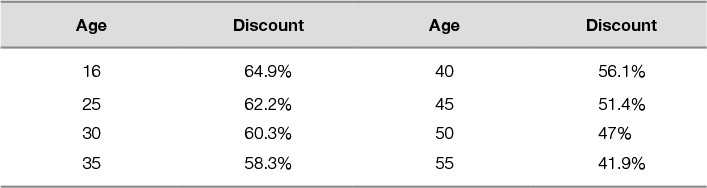

The ownership of the bond passes according to the terms of the deceased owner’s will or codicil. For probate and IHT purposes the value of the policy, which will depend on the underlying investment, is subject to a substantial discount to reflect the fact that the only benefit is the limited annual withdrawal facility that the bond provides as a right until the death of the youngest life assured. The amount of discount applied to the policy upon the death of the original owner depends on the age of the youngest life assured and typically varies between 40% and 65%, as set out in Table 22.2.

Encashing the policy

Although the policy terms would not provide a surrender value to the subsequent new owners of the bond, there is nothing to stop them approaching the insurance company at some stage in the future, possibly a few years after the death of the original owner, and requesting a non-contractual encashment of the policy. While each case will be assessed on its own merits, the standard operating position of the insurance company is to consider requests to surrender on a case-by-case basis where the contract does not include a surrender option.

This type of policy has been around for several years and all policies that have been subject to probate have successfully obtained the types of discounts suggested earlier. An additional benefit is that the disclosure of tax avoidance schemes (DoTAS) rules that have recently been extended to IHT planning arrangements do not extend to this policy because it was available prior to the introduction of the DoTAS IHT rules.

There are a few important points about this planning that need to be considered:

- The investor must not alter their will to make specific mention of the DVA at the time at which they invest.

- The insurance company is under no obligation to offer an early surrender value after the original owner’s death.

- This type of planning should be considered only once all other conventional planning has been considered.

Example

Take the example of Glenda, who is 85, in declining health but still mentally capable. As well as her house worth £650,000 she has about £1 million of capital in savings accounts, ISAs and funds (with minimal capital gains). Glenda wants to stay in her home but needs to fund care fees, living costs and property upkeep. In addition to her annual pension income of £30,000, she therefore needs at least £30,000 per annum from her capital. Glenda wants to hold all her capital on deposit and is not keen on investing in ‘business schemes’ or complicated trusts, but she is keen to minimise IHT on her eventual death.

Glenda decides, with the help of her daughter, Carrie (55), and son, Michael (52), to invest all her available liquid capital in a discounted value arrangement. As well as herself, Carrie and Michael, she includes her grandchildren, Luke (24), Maddy (21) and Ben (16), as lives assured on the policy. She invests the bond into a range of cash deposits that yields about 2% gross and no income tax is due on this interest as it rolls up tax-deferred within the bond. Glenda has an immediate option to withdraw up to £100,000 per annum from the bond, of which £50,000 will be tax-deferred. She decides to take just £30,000 per annum in arrears, which means that each year she can carry forward £70,000 to withdraw in a future year, of which £20,000 will be tax-deferred.

Glenda’s death about a year later occurs before she has taken her first annual withdrawal. At this stage the bond is worth £1 million after accounting for gross interest earned and policy charges. The bond, however, is valued for probate purposes at £350,200 due to the application of a 64.8% reduction factor based on the fact that the youngest life assured is Ben, who is 17 by then. Glenda’s executors claim a carry forward of her deceased husband’s nil-rate band and when aggregated with her own NRB the only taxable value left in her estate is the discounted bond value of £350,200. The IHT payable is therefore £140,080 rather than the £400,000 that would have applied had she done nothing – a saving of £260,000.

This type of policy is useful where BPR assets are not desired or not appropriate, or there is some doubt that the investor would survive the necessary two years for the BPR IHT exemption to apply. It does, however, need to be carefully considered in the light of the individual’s and their wider family’s views, needs and circumstances. In this regard the help and assistance of a caring, diligent and knowledgeable wealth planner familiar with such structures is essential.

The A&M plan

Up to the 2006 Budget, accumulation and maintenance (A&M) trusts offered a very effective way of giving capital to younger generations of the family, without either the underlying beneficiaries having an automatic right to the capital at age 18 or the capital in the trust forming part of their estates for inheritance tax purposes.

Typically, income and capital would be advanced to fund school fees and help with other expenses, such as gap-year trips. While the income and gains arising on the A&M trust were subject to 40% income and capital gains tax, if income were distributed to a beneficiary paying no or basic-rate tax, the beneficiary could reclaim all or some of the tax paid by the trustees. At least one beneficiary needed to have a right to trust income by the time they were 25.

Another useful feature was that the gift to an A&M trust was treated as a potentially exempt transfer for inheritance tax purposes. As such, there was no immediate charge to inheritance tax at the time the gift was made and after seven years the gift was outside of the donor’s estate. In the meantime, growth arising on the trust assets arose outside the donor’s estate.

Since 2006 new gifts to A&M settlements have been treated in the same way as those to discretionary trusts and are subject to an immediate charge of 20% if the gift, including gifts made to discretionary trusts within the previous seven years, exceeds the NRB (currently £325,000).

As we saw in Chapter 21, individuals who wish to gift assets to minor children now have the choice of gifting to a bare trust or to a discretionary trust. While for many these trusts will be perfectly acceptable, for some people they will not, for a variety of reasons including not wanting the beneficiary to have outright access to the capital at 18 or because they have already made the maximum gift into a discretionary trust within the last seven years.

An alternative approach

However, there is a way of making a gift to minor or adult children which:

- is treated as a potentially exempt transfer and thus avoids an immediate tax charge

- avoids the £100 income tax rule on parents who gift capital to their children via a bare trust

- provides virtually tax-free roll-up of income and gains

- provides access to some of the gift to fund education and other maintenance costs as required

- does not allow the child access to the capital automatically at age 18 but instead at a later age specified by the person making the gift.

Enter the accumulation and maintenance plan (see Figure 22.6). The basic concept is that the person making the gift invests in an offshore investment bond with multiple lives assured, ideally including the young person for whom the capital is intended. This should avoid the bond becoming subject to tax on the gain on the death of the person making the gift. The bond is then assigned to one or more people (this could include the person making the gift), who own the bond as bare trustee/s for the minor child. This is treated as a potentially exempt transfer and leaves the NRB untouched in lifetime. As long as the donor survives for at least seven years, the gift will fall out of their estate.

The child will become absolutely entitled to the policy at age 18, as is the case with any gift to a bare trust. However, the bond has special policy provisions that are specified at outset and have the effect of suppressing the surrender value of the bond until a certain date of the donor’s choosing. This could be when the recipient is, say, 25, or any other age the person gifting the money deems appropriate.

All income and gains arising in the bond roll-up are virtually tax-free (depending on the assets held) until ‘chargeable event’ occurs (see Chapter 15 – single-premium bonds). Such an event arises when the bond is totally encashed, a withdrawal is made of more than 5% per annum (cumulative) of the original capital, the death of all the lives assured on the bond or assignment of the bond for money’s worth. Currently, gains are taxed at the owner’s highest marginal rate, i.e. up to 45%, with no allowance for non-reclaimable withholding taxes. In certain cases it might be possible to time the chargeable event to arise when the beneficiary is either UK non-resident or pays only basic-rate income tax.

As the bond technically comprises lots of smaller segments, it is possible to time encashments over a number of years to minimise or defer tax. This type of arrangement works best for higher-rate taxpaying parents who wish to make substantial gifts to minor children who have a fair chance of becoming UK non-resident or basic-rate taxpayers when the relevant policy acquires an encashment value (top slicing relief may prove useful too, as may time apportionment relief for any periods of ownership while UK non-resident).

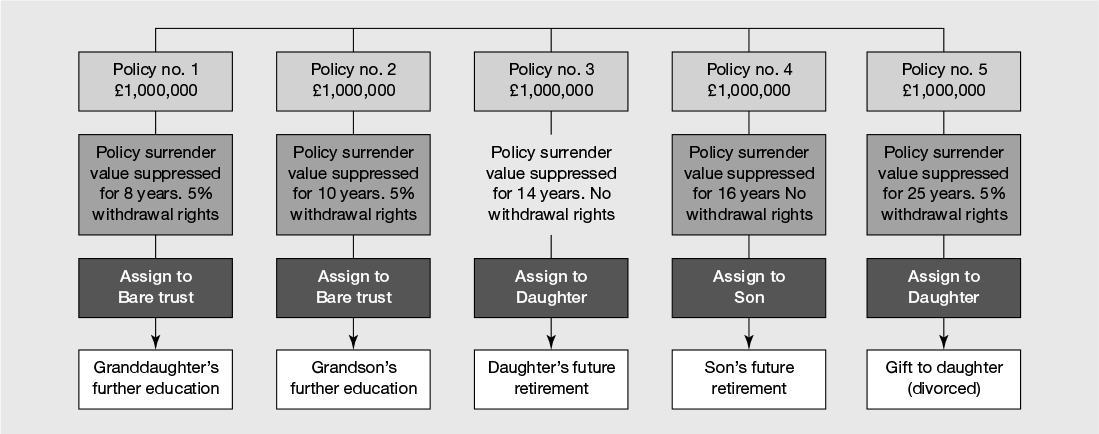

Figure 22.6 A&M plan

Source: Lombard International.

In the intervening period between the date the policy is gifted and the date that the full value of the bond becomes available, it is possible to specify that the policy can provide regular withdrawals to meet expenses such as education and other maintenance payments. As long as these are within the 5% annual allowance (with unused amounts from one year able to be carried forward to use in future years), no immediate tax charge will arise.

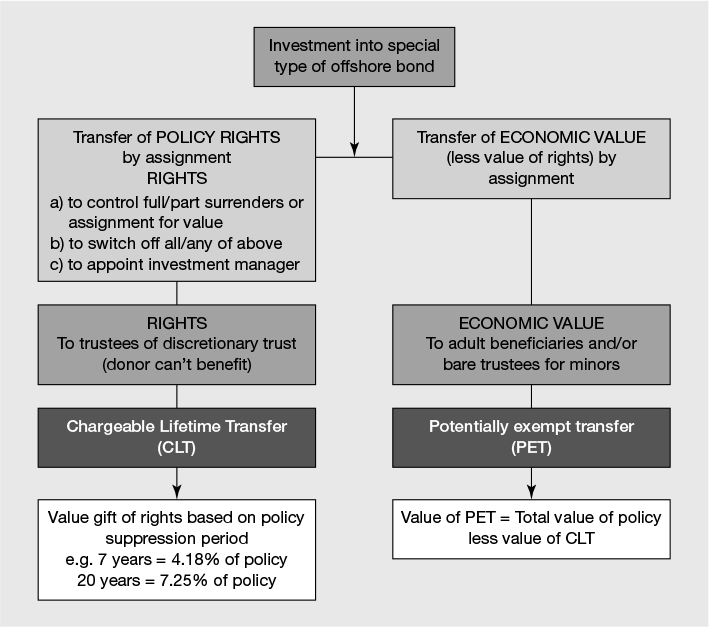

The flexible legacy plan

The A&M plan is taken a step further with the incorporation of additional policy features that make it even more flexible and potentially more tax-effective. These features include:

- the right to create an entitlement to part or total surrenders and to switch off or amend the entitlement after its creation

- a similar provision in respect of assignment of some or all of the policy for value.

These policy features are then assigned by the investor to the trustees of a discretionary trust, together with the right to appoint a discretionary investment manager. The investor who creates this trust is precluded from future benefit.

Figure 22.7 Flexible legacy plan

Source: Bloomsbury Wealth Management.

Once these policy features/rights have been assigned to the trust, the policy itself (including full economic value) can then be assigned directly to adult beneficiaries or to bare trustees to hold on behalf of a minor. Because the policy rights that have been assigned to the discretionary trust have a value, they serve to reduce the value of the potentially exempt transfer arising from the gifted policy. The exact value of the rights transferred to the trust will depend on the period for which surrender rights on the policy are suppressed, with longer periods giving rise to higher values. See Figure 22.7 above.

Example

The flexible legacy plan in action

Max and Cindy, who have not made any previous gifts, wish to make gifts of £1 million from each of them (i.e. £2 million between them) to each of their children, Mandy (23), Sam (20) and Josh (18). They each invest £1 million into three investment bonds, which are subject to the following terms:

- Each child can have full access to the capital in their policy at age 35.

- Each child is to be paid £20,000 p.a. from their policy in the interim.

- Consideration should be given to future requests for an advance of some or all of each child’s policy proceeds before their 35th birthday, to cater for changing circumstances.

Of the total gifts of £3 million from each parent, £180,000 will be treated as a chargeable lifetime transfer from each of them, representing the value of the additional policy features gifted to each trust based on the time period between now and when Mandy, Sam and Josh each reach age 35. The economic value of each policy, after deducting the value of the rights transferred to the trust, will be treated as a potentially exempt transfer to the adult children of £2,820,000 from both Max and Cindy, i.e. £5,640,000 in total.

No inheritance tax is due at outset and all future growth will arise outside Max’s and Cindy’s estates. If they survive the gift by seven years, the CLT and the PET gifts will fall out of their respective estates completely. Otherwise the gift of policy rights to the trust and part of the policy values gifted to the children will be deducted from Max’s and/or Cindy’s nil-rate band at the time of their death. An excess gift over the NRB will be subject to IHT at 40% on subsequent death unless death occurs between three and seven years, when it will benefit from a sliding-scale reduction in tax from 80% to 20% of the full amount due.

The A&M plan or flexible legacy plan will be suitable for those who want to make significant gifts and who:

- want to avoid the capital passing to the child automatically at age 18, but instead at an older age

- wish to make more substantial gifts

- want the bulk of the gift to be a potentially exempt transfer to avoid the 20% lifetime charge applicable to discretionary trusts

- have already made gifts made to discretionary trusts in the last seven years which have utilised the current £325,000 nil-rate band

- wish to pursue an investment strategy that balances capital growth and income with virtually no tax on an arising basis

- as parents, want to avoid the £100 income limit applicable to a bare trust or the additional tax that applies to dividends distributed under a discretionary trust

- think that there is a good possibility that the recipient child will be either a non/basic-rate taxpayer or a non-UK resident on encashment.

Foundations

A foundation is a legal entity that combines the features of a trust and a company. It is similar to a company, in that it is a distinct corporate legal entity managed by a board of directors in accordance with its charter and regulations, but it has no shareholders. It is similar to a trust in that it has one or more objects that may be a purpose (charitable or non-charitable) and/or be for the benefit of one or more beneficiaries.

The primary use of a foundation is for private wealth management, including:

- as an alternative to a traditional trust where international families are not familiar with the concept of a trust or find them complicated to understand

- a more acceptable vehicle than a trust in certain jurisdictions that require a higher degree of transparency for wealth-holding structures

- to control global charitable assets and giving

- as a means of holding ‘orphaned’ special purpose vehicles

- to carry out general commercial transactions.

Foundations are therefore a truly international legal structure that can be used to create sophisticated inter-generational and charitable planning and are usually based in places such as Jersey, Latin America, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg and Malta.

Foundations are unlikely to be suitable for most families, unless the wealth is substantial (in the tens of millions of pounds’ worth of assets) or where a sophisticated tax structure is in place, such as an international purchased life annuity.