CHAPTER 6

![]()

Champagne

In the eyes of the ordinary consumers, Champagne, if dear, has at least the merit of being what it is represented to be, which is more than can always be said of other wines figuring on retailers’ lists, and the public, as a body, prefer certainty, with high charges, to uncertainty, even when baited with low prices.

—Ridley’s, January 1883:3

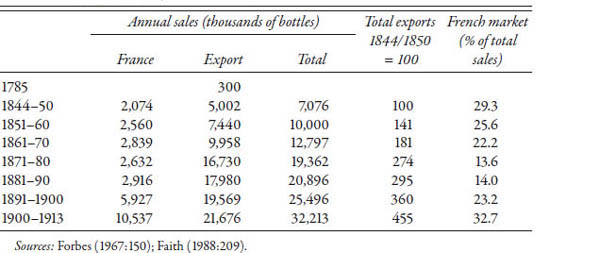

CHAMPAGNE PRODUCERS were the most successful of all producers in establishing brand names, informing consumers of wine quality, and associating the drink with the needs of the rapidly changing lifestyles of the middle and upper classes in rich urban societies during the nineteenth century. Output increased from just 300,000 bottles, equivalent to the production of about 150 hectares of vines on the eve of the French Revolution,1 to almost 40 million bottles by 1910. The major champagne maisons, or houses, successfully exploited three interconnected features to achieve this growth. First, they developed new wine-producing methods that allowed quality champagne to be produced with the desired level of pressure and benefited from the high degree of specialization in production.2 Second, the prosperity of the champagne industry was closely linked to the growth of the global economy, with exports accounting for over 85 percent of all sales in the 1870s and 1880s and two-thirds in the 1900s. Finally, the industry was a pioneer in modern marketing methods, which allowed the maisons to exploit major economies of scale in marketing.

The production of sparkling wine is not unique to the Champagne region. In France the sparkling wines from Gaillac (southwestern France) and Limoux (Languedoc) date from the Middle Ages, while those from Saumur (Loire valley) competed with champagne in both the domestic and international markets in the nineteenth century. Italian spumante and Spanish cava also enjoyed local popularity before 1914.3 Yet none of these wines came anywhere near to providing serious competition with those produced in Reims and Épernay. The grape growers and champagne houses inevitably claimed that a major part of their success was the terroir, which precluded the possibility of imitating the drink elsewhere. Yet the comparative strength of the champagne houses lay, and continues to do so, in their ability to blend a wide variety of grapes and wines to obtain the required characteristics of the final product. The region was relatively close to many of Europe’s leading courts, which in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were the markets for the small quantities of champagne consumed, suggesting that the association of champagne with luxury was not just a clever marketing invention of the nineteenth century. As with port, sherry, and claret, trade was concentrated in the hands of a small number of houses, and André Simon, writing in 1934, noted that “there are barely a score of Champagne shippers of world-wide repute, and of these a dozen at the most could be described as being in a large way of business, but not less than seven of them date back to the eighteenth century, and all the others are over or else nearly a hundred years old.”4

Most of the large champagne houses purchased the greater part of their grapes from the thousands of small growers and were successful because they enjoyed the economic resources and technical skills to organize the highly specialized tasks involved in the conversion of grapes into vintage champagne. The fact that fine champagne was made from the limited supply of quality grapes, and that grape and wine production were highly specialized, labor-intensive activities, led to production costs being significantly greater than in most other regions. However, by marketing the drink as a luxury, and by successfully defending their reputation for quality, shippers were able to charge high prices and enjoy good profits. The 1880s and 1890s were golden years for both growers and producers. The growers’ prosperity was ended by the appearance of phylloxera and subsequent decline in local harvests, so that the rapidly developing demand for cheap champagne from the 1890s in the domestic French market encouraged the houses to look elsewhere for their grapes. The disastrous harvests in the Marne between 1907 and 1911, which were only a third the size of those in the prephylloxera years of 1892 to 1896, led to thousands of local growers demanding the creation of a regional appellation and an end to the use of outside wines being used to make “champagne.” Protest were bitter because disputes occurred over where the borders of the appellation should be drawn.

This chapter looks briefly at the early history of champagne and the dramatic increase in production in the late nineteenth century, the organization of the commodity chain favoring the champagne houses over British retailers, the response of the champagne houses and small growers to the phylloxera crisis, and the collapse of local production and importation of large quantities of outside wines after 1906. In the end, despite the crisis, the champagne producers were more successful than those in other wine regions in controlling the quality of their product.

THE MYTH OF DOM PÉRIGNON AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHAMPAGNE

The Champagne region was famous for its table wines long before the production of sparkling wines.5 Situated on the crossing of important trade routes, the medieval trade fairs of Champagne (including Provins and Troyes) were among Europe’s most famous in the Middle Ages. Reims was the principal gateway for the export of wines from Champagne and Burgundy from at least the fourteenth century, while cheaper beverage wines were transported from Épernay along the Marne and Seine rivers to Paris.6 In the second half of the seventeenth century, the region’s most famous wine was Sillery, which, according to Nicholas Faith, “was a brand name for a blend of wines, only part of which came from the village of the same name.”7 About the same time the Marquis de Sillery, the exiled Marquis de St-Évremond sold a sparkling wine in England that soon became fashionable in the court of Charles II.8

Champagne is a blended wine produced on the very edge of Europe’s northern limits of wine production. The major grape varieties used are the pinot noir, followed at some distance by the pinot meunier and the chardonnay. Grapes are grown in three major regions of the Marne department: the Mountains de Reims, the Marne valley, and the Côte d’Avize (Côte des blancs). Sparkling wines develop naturally when the cold winter weather halts fermentation prematurely, allowing the remaining sugar to begin a secondary fermentation when the temperature warms once more in the spring; if the wine has already been bottled, it retains the carbon dioxide and allows the bottle to “pop” when it is opened, with copious amounts of bubbles produced when the wine is poured. It seems likely that the first sparkling wines (vins mousseux) were produced by accident and considered undesirable, not just because there was little demand for this type of wine, but because large numbers of bottles were broken and the wine lost, as producers had little idea of how to control the process.

Although historians have dismissed the popular myth that attributes the discovery of champagne to Dom Pérignon, a blind monk who was cellarer at the Abbey of Hautvillers in Épernay between 1668 and 1715, they continue to give him a key role in its early development. In Harry W. Paul’s historical study of the science of wines, Dom Pérignon is a “revolutionary oenologist . . . worthy of joining that happy band enjoying mythical status such as Pasteur, Ribéreau-Gayon, and Peynaud, because of his ruthless emphasis on quality both in vines planted and those kept in production and on the importance of the quality and maturity of the grapes pressed.”9 Rather than an inventor as such, he was a keen observer and experimenter, whose contemporary fame rested on the fact that he consistently produced excellent wines in a region where this was notoriously difficult. Pérignon used black grapes, especially the pinot noir, for white wine production (blanc de noirs). White wines produced from white grapes quickly turned yellow and lost their delicacy after a year, but those produced using the pinot noir stayed white and maintained their quality for three or four years. As Paul notes, nature therefore “compensated for the crudity of the technology of vinification, which were then incapable of preventing the oxidation of the wine.”10 Special care had to be taken, however, so the skins did not color the wine, and yields from the pinot noir were significantly smaller than those of white varieties.

Dom Pérignon was also extremely successful at blending the grapes that were received as tithes or produced on the abbey’s estate. Blending was essential, as the quality and characteristics of the grapes produced on each plot varied significantly, as well as from one harvest to the next. Another consideration was the need to add the correct amount of sugar: sufficient to produce the secondary fermentation and create the sparkle, but not too much, which would lead to excessive numbers of broken bottles.11 Finally, it appears that Pérignon took advantage of the improved bottle-making techniques that were being introduced in England during the 1660s. Stronger glass bottles, hermetically sealed by using corks, allowed more of the carbonic acid gas to be retained without breaking the bottles. According to the writer Michel Dovaz, champagne production can be divided into a “before” and “after” Pérignon: “B.P.: few bottles, no or hardly any bubbles, no corks, none of the excellent blanc de noirs, no wine that kept, etc. A.P.: thanks to him and also to others, especially brother Oudart, the sparkling wine of the Champagne came into existence, sold well and dear, and was put on the road to a real commercial career.”12

This early momentum associated with Dom Pérignon was not maintained. The high production and transportation costs and the fickle nature of demand made most growers and négociants reluctant to switch from producing red table wines to sparkling ones. Yet by the end of the eighteenth century this was beginning to change. The historian Thomas Brennan has argued that Labrousse’s thesis on the flourishing state of French viticulture before the 1770s does not hold for the Champagne region, and the decline in trade between Épernay and Paris forced growers to develop new products and markets and thereby challenge the brokers who dominated the old trade.13 As a result, exports grew from about 300,000 bottles in 1785 to five million by the 1840s. Yet as late as 1832 the Marne produced only 50,000 hectoliters of sparkling wines, compared with 310,000 hectoliters of ordinary red wine for local use, and 120,000 hectoliters of quality red for export.14 On the eve of the First World War this had changed, and champagne sales were over 32 million bottles, or roughly 240,000 hectoliters (table 6.1), while the market for table wines had almost disappeared in the face of competition from the Midi.15

TABLE 6.1

Sales of Champagne, 1850–59 to 1900–1909

Behind this growth in champagne sales there were significant changes in the methods of wine making and the nature of the wine itself. One major advantage was the introduction of disgorging to remove the sediment and create a clean, transparent wine. The secondary fermentation produces sediment composed of a variety of substances, including dead yeasts, gum arabic, tartrate, calcium, and bicarbonate of potassium, which had to be removed with the minimum amount of loss of pressure inside the bottle.16 Traditionally the wines were decanted and rebottled, but this process was beginning to change in the mid-1810s, as John MacCulloch noted:

To remove this [sediment] and to render the wines marketable, those of the best quality are decanted clear into fresh bottles in about fifteen or eighteen months, when the wine is perfected. A certain loss, amounting to one or two bottles in a dozen, is sustained by their explosion previous to this last stage. Another process is sometimes adopted for getting rid of the sediment without the trouble of decanting in this mode; the bottles are reserved in a proper frame for the purpose during a certain number of days so as to permit the foulness to fall into the neck; while in this position the cork is dexterously withdrawn and that portion of the wine which is foul, allowed to escape, after which the bottle is filled with clear wine, permanently corked and secured with wire and wax.17

The new system was a two-stage process, known as remuage and dégorgement. The bottles were first placed in the riddling frame, which comprised two planks of wood placed in position on the floor in the form of an inverted V. Each plank was pieced, and up to sixty bottles of champagne were placed neck-down into the slots. Skilled workers rotated, oscillated, and tilted the bottles slightly each day for several weeks until the sediment was all concentrated in the bottle’s neck next to the cork. The temporary cork was then carefully removed from the bottles to allow the carbonic acid gas to escape and with it the sediment. The quick movements of skilled workers resulted in little wine being lost. In 1889 an easier method was developed, the dégorgement à la glace, which involved freezing the head of the bottle in calcium chloride and allowing the sediment to be expelled as an ice pellet. With both methods, a small amount of wine and sugar was then added to create the desired type of champagne (brut, sec, doux, etc.).18

Wine quality was also improved when André François showed in 1837 how to determine the exact amount of sugar needed to obtain a satisfactory secondary fermentation. According to André Jullien in his treatise of 1816, bottle losses varied between 15 and 20 percent, and sometimes even 30 or 40 percent; in 1833 Moët & Chandon lost 35 percent and in 1834, 25 percent.19 The greater control of the secondary fermentation, together with the continuing advances in bottle-making techniques, reduced the losses from breakage from about 25 percent in the late 1850s to 10 percent by the 1870s.20

ECONOMIES OF SCALE, BRANDS, AND MARKETING

Property was highly fragmented in the Marne, with 14,430 growers each owning less than a hectare of vines, 3,202 having between 1 and 5 hectares, 89 between 5 and 10, and only 18 with more than 20 hectares.21 The vast majority of the growers sold their grapes to a very small number of firms that possessed the necessary capital and skills to produce and market champagne. In the 1880s 83.4 percent of production was exported, and the figure for the best champagnes was probably even higher. The Syndicat du commerce des vins de Champagne, established in 1882 by the largest houses to promote their interests, never had more than a hundred members, and it was reported in 1908 that nine-tenths of the exports of fine champagne were sold by just thirty-four houses.22 The growing market power of these houses, especially concerning the setting of grape prices, worried growers even before the appearance of phylloxera.23

One of the reasons why champagne was more expensive than other wines was that it required greater labor inputs. The topsoil was shallow, and every four years or so a mixture of sand, clay and the cendres noires (a form of impure lignite, containing iron, sulfur, and oligo-elements) was quarried and spread on the vines. The result was that the thickness of the topsoil was maintained over the centuries and has become “an artificial creation, a creation . . . of such complexity that it is never likely to be successfully reproduced or imitated elsewhere.”24 On the prephylloxera vineyards, up to fifty thousand wooden stakes were driven into the ground each spring to support the grapes and removed after the harvest to avoid them rotting in the ground. Pruning restricted the yield of the vine and ensured that the grapes were grown close to the ground, allowing them to capture more of the heat, but obliging the harvesters to bend double to collect them. Grape growing in Champagne was also especially risky, with grapes in danger of damage from late spring frosts or summer hail, as well as downy mildew and pourriture grise produced by excessive summer moisture. Most growers reduced their exposure by working the vines only part-time. Finally, and unlike other French wine-producing regions, only a limited number of growers pressed their own grapes.25 The champagne houses selected their grapes from a wide variety of vineyards to obtain grapes with different characteristics. According to one contemporary:

The aim is to combine and develop the special qualities of the respective crûs, body and vinosity being secured by the red vintages of Bouzy and Verzenay, softness and roundness by those of Ay and Dizy, and lightness, delicacy, and effervescence by the white growths of Avize and Cramant. The proportions are never absolute, but vary according to the manufacturer’s style of wine and the taste of the countries which form his principal markets.26

To achieve this, the leading firms established crushing and pressing facilities in the main villages. Moët & Chandon, which was unusual in that it owned 365 hectares of vines itself, had facilities in seventeen different villages. These vines produced the equivalent of about 1.3 million bottles, but because this was “utterly inadequate” to cover the firm’s demand, large quantities of grapes were also bought from local growers. As the wine was stored in bottles rather than casks, the champagne cellars also had to be considerably larger than those found elsewhere, and the need to control carefully the temperature of the wines during the secondary fermentation required the cellars to be much deeper. The chalk soils of the region were simple and inexpensive to dig out, but sufficiently strong for a cellar. Moët & Chandon’s cellar in Épernay had an aggregate length of over 10 kilometers and stored between eleven and twelve million bottles and 25,000 casks of wine, with the firm employing 20 clerks and 350 cellarmen, although the total payroll came to 1,500.27

The champagne houses, just like those in Porto and Jerez, blended wines to meet the different demands of the consumer. However, unlike port and sherry, champagne had to be bottled before being shipped, and this allowed the maisons to control the wine from production to consumption and their brands were considered an important guarantee of purity. The champagne houses developed their house wine by careful blending and kept extensive stocks in order to supply wines of a “similar type and of uniform quality, year after year, irrespective of the vagaries of the weather.”28 Labels and branded corks informed the consumer that they were drinking not just champagne, but Bollinger or Roederer. Selling champagne was therefore relatively easy for retailers. The successful branding of champagne by the leading houses led to an increase, not a reduction, in prices for consumers, and even Britain’s giant retailer Gilbeys started selling producer-branded champagnes rather than its own from 1882.29

Product development was another major area of success. Champagne was originally sweetened significantly, in order to hide “the sharpness of youth which time alone could have toned down.”30 British retail merchants made a number of attempts to sell dry champagne in the mid-nineteenth century, but it only became important in the late 1860s, and it was not until the 1874 vintage that brut champagne was generally available and sold by most of the leading houses.31 According to André Simon, the introduction of dry champagnes made it fashionable in some circles to drink it at dinner and helped to increase consumption in England from three million to over nine million bottles between 1861 and 1890. Sweet dessert champagnes remained the rule throughout France, together with some export markets, such as Russia.32

A taste for dry champagnes allowed the creation of “vintage” champagne, which consisted of a select blend of wines produced in a specific year that was noted for its excellence and could be marketed at considerably higher prices than the ordinary house wines. Vintage champagnes became fashionable and prices rapidly increased, greatly outstripping the costs of storing the wines. Thus the Clicquot 1884 vintage sold for 94 shillings a dozen when it was released on the market in 1891 but reached 165 shillings by 1898; Moët & Chandon’s vintage of the same year increased from 88 to 260 shillings between the same dates.33 The shippers allocated wines to retailers before they were actually released, and these often changed hands several times before the wine was delivered. Wine merchants encouraged consumers to purchase vintage wines, and inevitably some shippers were tempted to increase the supply, eventually leading to a decline in their novelty.34 André Simon, writing in 1905, noted that “the 1889 and 1892 vintages being excellent wines, and sold on the market at a highly favourable time, mark the apogee of the vintage Champagne boom from the point of view of the public.”35 Consumption in Britain reportedly then declined in the “clubs and the less fashionable Hotels and Restaurants” and was also negatively influenced by the growth in entertaining in restaurants rather than private houses.36 Once more an increasingly critical press argued that poor-quality grapes were being used in champagne production, which affected demand, especially for the cheaper wines.37

Although exports to the major Britain market started falling in the late nineteenth century (fig. 4.4), total sales of champagne continued growing until the First World War, driven by the growth in French demand (table 6.1) and heavy advertising. Mericer, an important producer of cheap wines, received considerable publicity when it constructed the largest barrel in the world, containing the equivalent of 200,000 bottles, for the 1889 Universal Exhibition and had it towed to Paris by twenty-four white oxen in a journey that took three weeks. The same house commissioned one of the first advertising films for the 1900 Exhibition and received widespread publicity when a giant balloon broke loose and transported nine unsuspecting drinkers and their waiter from Paris and deposited them unhurt sixteen hours later in the Austrian Tyrol, where the company was fined twenty crowns for importing illegally six bottles of champagne.38 Other marketing strategies were less dramatic. As large quantities of champagne were drunk in hotels and restaurants, some shippers paid corkage fees to waiters, amounting to a fee for every bottle of their wine that was sold.39 Hoteliers, however, learned that the system could also work to their advantage, and a certain Messrs. Gordon demanded a payment of £500 to stock a particular brand of champagne in their five hotels.40 Brands became everything, and one writer noted in 1890 that “within ten years we will no longer recognise the name of champagne, but only those of Roederer, Planckaert, Bollinger, without any idea what the wines will be made out of.”41

Champagne sales increased almost five times from the late 1840s to the 1900s, partly as a result of an increase in the area of vines and better wine-making skills, but also because of the use of outside wines, leading to a decline in quality.42 Kolleen Guy notes that fraud changed from “a peripheral concern in the 1890s” to “the central issue for producers of both ordinary and fine wines at the turn of the century.”43 The best champagnes continued to be sold under the manufacturer’s brand name and vintage and were not adulterated, but the reputation of other houses was questioned. The situation was made considerably worse between 1908 and 1910 when the local grape harvests failed, encouraging the widespread use of cheap white wines from other regions. The irony was not lost on local growers that some houses, which had gone to court to protect the “Champagne” name, were now themselves using outside wines. Unlike Bordeaux, the debate on establishing a regional appellation took place against the background of the destruction caused by phylloxera, and not overproduction.

THE RESPONSE TO PHYLLOXERA

Phylloxera was first discovered in the Champagne region in 1890, making it the last major wine-producing area in France to be infected. Despite this delay, the question of how to respond to the disease created fierce conflicts in the local community. Like the leading growers in Bordeaux, the big champagne houses were concerned about the quality of wine produced from the new grafted vines and therefore wanted to do all that was possible to preserve the traditional French rootstock. Unlike the Bordeaux growers, however, most champagne houses were not major producers of quality grapes themselves but depended on hundreds of small growers. How the small winegrowers responded to phylloxera would have major implications for the big champagne houses.

A comité d’étude et de vigilance contre le phylloxera was created in 1879 to develop a plan of action, consisting mostly of “agricultural professors, large landowners, and négociants.” Several visits were organized to the Midi, and this led some to argue that the spread of phylloxera was caused by poor cultivation, and therefore it would never be a threat to the growers of quality grapes for champagne.44 The appearance of diseased vines on the edge of the Marne in July 1889 challenged this particular belief, and Gaston Chandon of Moët & Chandon purchased and destroyed the infected vineyard, while the Syndicat du commerce proceeded to do the same when a further 2 hectares of diseased vines subsequently appeared.45

Even if immunity to phylloxera was now recognized as impossible, the experience of fine wine producers in Bordeaux suggested that the destruction could be delayed, perhaps indefinitely, by the use of chemicals. In Bordeaux the large growers had used their own resources to protect their own vines and were relatively indifferent to the plight of small growers, whose wine they did not buy. The dependence of the large champagne houses on the thousands of small growers required them to keep the whole region disease free for as long as possible. This in turn required a collective response, as all diseased vines had to be uprooted and destroyed, and the land treated with chemicals to be sure that no aphids remained. To be successful, all growers had to participate, as phylloxera would become quickly established if some remained outside the syndicate. The institutional arrangement to oblige all growers to participate, and thereby remove the potential problem of free-riders, was the law of December 1888. This allowed a départemental syndicate to be created if two-thirds of growers possessing three-fourths of all vines, or three-fourths of all growers with two-thirds of all vines, supported the project. In June 1891 it was claimed that 17,370 growers (67.5 percent of the total) and 9,772 hectares of vines (76.2 percent) had agreed, and a local Association syndicale autorisée por la défense des vignes contre le phylloxera was authorized the following month. All growers in the Marne were obliged to pay dues, and the syndicate’s officials had the legal right to enter any property and uproot and destroy any diseased vines. Growers were to be compensated.

Disputes began immediately. A number of growers claimed they had shown interest only in the possibility of establishing a syndicate, rather than supporting a specific project.46 Others claimed that some of the signatures were not those of vine growers, or that they belonged to deceased growers. Conflicts also arose over the annual fee, with smaller growers demanding that the better, and hence more valuable, vineyards should pay more than the less valuable ones. However, the major area of dissent was over the methods used to tackle phylloxera. The small growers wanted to encourage the use of experiments with new American vines so that they could replant as quickly as possible, while the large champagne houses wished to keep American vines (and hence possible infection) away from the Marne for as long as possible. This difference in strategy quickly became apparent, and the list of candidates presented by the large landowners (and champagne firms) for the steering committee was challenged successfully by René Lamarre, whose own list predominantly comprised small growers.47 Yet success for the growers was short-lived: when the committee met in May 1892, the original twenty-five members found that their numbers had grown to eighty-three. Additional financial contributions had been obtained from the Reims Chamber of Commerce, the Syndicat du commerce, and other institutions, and this legally allowed them to official representation, thereby snatching control away once more from the small growers.48 Officials were assaulted when they tried to remove diseased vines, and the police estimated that in 1894 nearly 75 percent of vignerons were actively opposed to the association.49 Small growers now drew up a new petition calling for its dissolution.

Why did the association fail? Lucien Lheureux, a writer generally favorable to the négociants’ position, noted in 1905 that if the syndicate had operated as planned, it might have delayed the spread of phylloxera by a decade or so.50 In fact, although phylloxera had been found on the edge of the Marne in 1889, only 659 hectares were infected, or 4 percent of the total area, as late as 1900. Yet growers had several worries concerning the Association syndicale. First, the big champagne houses were relatively immune to phylloxera. If their own vines, or those of growers from whom they habitually bought, were destroyed, they could look elsewhere for their grapes. More important, they also carried large stocks of wines in their cellars, and they continued to do business successfully during the worst of the epidemic. By contrast, those small growers whose vines were destroyed immediately lost their livelihood. However, these fears clearly belonged to the future, as the area infected in the whole of the Marne was still minimal when the Association syndicale disappeared in 1895. A more immediate preoccupation was the high profile of the Syndicat du commerce within the Association syndicale, which created considerable unease among many growers. Many believed that the Syndicat du commerce had displaced the market by acting as a monopoly and unilaterally establishing grape prices and controlling sales. The difficulties faced by the villagers of Damery in establishing a producers’ cooperative at this time, for example, were attributed to the supposed boycott of its wine by the champagne houses.51

Finally, by the 1890s American vines were being successfully planted in large areas of France. Nationally the area replanted jumped from 75,000 hectares in 1885 to 436,000 in 1890, and by this date the area of replanted American vines outnumber by more than four to one the total area that was being treated chemically or flooded (table 2.3). Small growers in the Champagne region demanded public institutions to experiment and find which vines were most suitable to the chalk soils of the Marne, and to determine which French scions produced the best wines. A policy limited to just the elimination of vines was unpopular with small growers because, and as one petition to the mayor of Épernay put it, “Phylloxera is at our doors and a large part of the vines are anaemic and sterile. We need to regenerate our vines . . . and to profit from the experience of others before we lose everything.”52 In the face of widespread opposition, the Association syndicale was quietly disbanded in 1895.

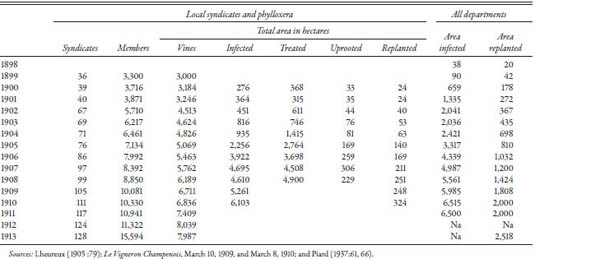

The disappearance of the association did not imply the end of collective action against phylloxera. It was quite the opposite. As in Bordeaux, small growers formed local village syndicates to help fight the disease. In Bouzy in 1900, for example, growers who owned 186 of the village’s 215 hectares of vines belonged to the local syndicate. A further 14 hectares belonged to Chandon, who not only treated these vines privately but contributed 800 francs to the local syndicate.53 In March 1898 the Association viticole champenoise (AVC) was established as an umbrella organization on the initiative of twenty-four of the leading champagne houses to provide funds and practical help to individual local syndicates. As article 3 of its statutes noted, the AVC was established not only to fight phylloxera and other vine diseases, but also to help replant diseased vines.54 A research station was established in the village of Ay, and the AVC, together with Moët & Chandon, was at the forefront in providing workers with the skills to grow the new vines.55 For example, in 1902 seven syndicates participated in a competition for grafting new vines organized by the AVC, a figure that doubled the following year and included 112 participants. Prizes were awarded according to the quality of work, rather than the speed.56 By 1900 almost four thousand growers grouped together in 39 syndicates were receiving help from the AVC, and they were treating chemically about a tenth of their vines. These figures increased to almost 11,000 members and 117 syndicates in 1911 (table 6.2).

Small growers were happy to accept help from the AVC because, unlike with the Association syndicale, they retained full control over local decision making, and from an early date the AVC helped with replanting rather than just destroying diseased vines. It remained active until 1938. The area of vines in the Marne drifted lower, from 15,640 hectares in 1898 to 13,870 in 1908, before falling to 12,790 hectares in 1913. The shortage of chemicals and the disruptions caused by the First World War finally allowed phylloxera to spread rapidly, and the area slumped to 6,900 hectares in 1919.57 The Syndicat du commerce initially played no role in the AVC, although it contributed 400,000 francs in 1908 to help growers whose harvest had been devastated by mildew, and who lacked funds to purchase the necessary chemicals.58

Yet if the local syndicates and the AVC helped absorb the shocks caused by phylloxera, growers soon faced another, even greater problem. While growers’ production costs were increasing because of the need to purchase chemicals to fight disease, their incomes declined steeply as a result of a combination of low grape prices and poor harvests. The continual growth in champagne sales was met by outside wines being sold as champagne, and local growers turned to the 1905 legislation on adulteration and pure food to recapture some of their lost market power.

ORGANIZATION OF A REGIONAL APPELLATION

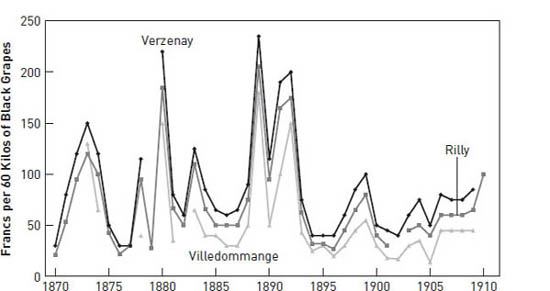

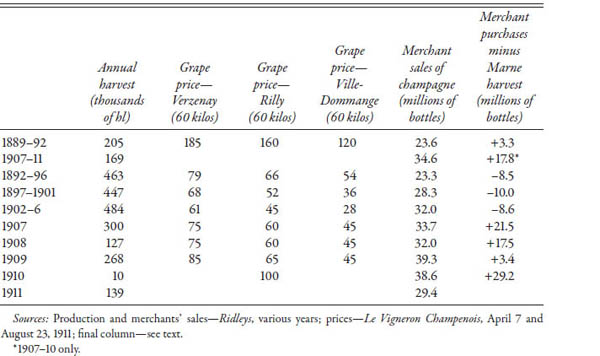

The wine crisis in the Marne was brought about by the destruction of local harvests. Augé-Laribé estimated 350,000– 400,000 hectoliters as a “normal harvest,” a figure that was reached seven times during the decade 1897–1906 but not once over the next five years (table 6.3).59 It is true that during the five years between 1888 and 1892 harvests fluctuated between only 127,000 and 278,000 hectoliters, but the grapes in these years were of a high quality, and growers were compensated by prices two or three times higher than normal years (fig. 6.1 and table 6.3). By contrast, late rains rotted part of the 1907 harvest, and that of 1908 was devastated by mildew. The 1909 harvest was small but of good quality, but the 1910 harvest was almost totally lost because of mildew and cochylis. Finally, drought caused the 1911 harvest to be very small, although of excellent quality.60

TABLE 6.2

Phylloxera and Local Syndicates Receiving Help from the AVC in the Marne

TABLE 6.3

Production, Prices, and Wine Sales in the Marne, 1889–1911

As table 6.3 suggests, the low prices and small harvests were only part of the story. Merchants were actually selling more wine, even though the harvests for the five years between 1907 and 1911 were only a third of those between 1902 and 1906. This was achieved in part by the champagne houses drawing on the stocks of fine wines that they had in their cellars. Gilbey, for example, was often at pains to argue in the British press that neither phylloxera nor mildew threatened the supply of fine champagnes for consumers. In 1904 it was noted that the Marne produced 348,000 hectoliters of wine, equivalent to 84,260,000 bottles. Even if this figure is reduced to 60 million because of production losses, it still dwarfs the sales of 25 million bottles that year. Some therefore argued that there was no need to worry about phylloxera.61 Yet this assumption was mistaken. In the first instance, figures for the total harvest, or merchants’ sales, provide little information concerning quality (and hence prices). Henri Sempé, for example, notes that only half the 1897 harvest could be classified as vins supérieurs, which sold for 125 francs per hectoliter, while vins ordinaires sold at about a third this figure.62 André Simon, writing in 1905, noted that the production on average of grands crus was 9 million bottles (produced on 3,100 hectares), while that of premier crus was 11.5 million (3,867 hectares), giving a total of just over 20 million bottles.63 Finally, there was about 8,000 hectares more “which yield too rough a wine to be used for sparkling champagne; much of this wine is, and the whole of it should be, drunk on the spot as a vin ordinaire.”64 When the quality of the local harvest was poor or insufficient, the temptation for producers of cheap champagne to seek alternative supplies from outside the region was strong. Indeed, as in Bordeaux, merchants argued that without the flexibility to choose the most suitable grapes regardless of their origin, neither they nor the local growers would be able to sell their wines in bad years.65

Figure 6.1. Grape prices in the Champagne region. Source: Le Vigneron Champenois, April 7 and August 23, 1911

The increased demand for champagne also hid an important change in the market because, if total sales increased by 51 percent between 1889–90 and 1907–11, exports grew by a relatively modest 18 percent. By contrast, consumption in the French domestic market tripled, from 4.4 to 13.2 million bottles. French consumers preferred the cheaper vins de deuxièm choix, and smaller firms, catering to this market, became increasingly important.66 Between 1905 and 1909, 48 percent of the sales in Épernay (6.9 million bottles) and 23 percent (4.3 million) from Reims were sold in France.67

The worsening economic situation of many growers became apparent after 1907. An estimate of “outside wines” bought by merchants is shown in the last column of table 6.3. The annual wine production in the Marne has been converted into an equivalent to that used by merchants, by using the same coefficients as given in Le Vigneron Champenois.68 This can be considered as the potential annual supply of local wine for merchants. Actual purchases by merchants have been calculated by adding to domestic and foreign sales the changes in annual stock levels (the year runs from April to March). The figures for the potential supply have been subtracted from the actual purchases, with a positive figure in the table implying that merchants were buying from outside the Marne, and a negative figure meaning that some local wines were being left unsold. This estimate is not without its problems, not least because many local wines were not used for champagne, as André Simon noted, and the fact that the agricultural year was different from the commercial one being used. However, table 6.3 suggests that massive purchases were made by merchants from outside the region after 1907, and that this was a relatively new situation, both with respect to years of relatively abundant local harvests (1892–1906) and to previous years of local harvest shortages (1889–1892).

The prosperity of the industry encouraged the champagne houses to be energetic in protecting both their private brands and the general reputation of champagne. The Syndicat du commerce was established in 1882 precisely to help monitor the industry, and the champagne houses prosecuted individuals who infringed their own brands under the 1824 law. Another area of concern was to convince the courts that the word “champagne” was not a generic name for any sparkling wine. The decision in 1889 by the Cour de Cassation, France’s highest tribunal, made it illegal for producers from outside the region to use the words “champagne” or “vins de champagne” to describe their wines, but the maisons were still legally allowed to buy wine from outside the region for bottling at Reims or Épernay, to be sold as champagne. Another activity that remained uncontrolled was the purchase of must in the Marne for manufacture in Germany, where import duties on grape juice were lower than on champagne.

The Syndicat du commerce noted in 1904 that its statutes required that all wines using the name champagne be produced from grapes grown and fermented in the region.69 Yet growers argued that the use of outside wines was common, and that the statutes of the Syndicat du commerce provided only a voluntary code of conduct. Therefore, while the firm Mercier was expelled from the Syndicat du commerce when it refused to stop sales of wines to Germany and Luxembourg where they underwent their second fermentation, this decision was not made public.70 Another problem was that if the Syndicat du commerce represented the large houses, there were a significant number of smaller ones supplying the growing market for cheap champagnes who were not members, precisely because this was not in their interests. The rapidly growing French market for cheap champagne also attracted the attention of some of the leading houses, although they took care not to sell cheap wines under their own brand. The persistence of poor harvests between 1907 and 1911 forced many houses, including those of the Syndicat du commerce, to look elsewhere for supplies for this new market.

The growers’ response to phylloxera, namely, the creation of local syndicates and the AVC, provided a useful rehearsal to confront the new situation of persistent low prices, devastated harvests, and wine purchases by champagne houses from outside the Marne. In August 1904 a new growers’ organization was established, the Fédération des syndicats viticoles de la Champagne, with the specific aim of controlling fraud. Its first leader was the moderate Edmond Bin, and perhaps in normal circumstances a compromise over wine purchases would have been reached with the merchants. The Syndicat du commerce was worried itself about the declining reputation of the name “champagne” and agreed with the Fédération that the boundaries of the “true” Champagne were the three arrondissements of Épernay, Reims, and Châlons-sur-Marne. Representatives of the Marne were instrumental in attaching an amendment to the 1905 legislation on consumer protection a clause which included reference to establishing regional appellations.71 Despite this agreement between the two major organizations, the following years saw bitter conflicts, exploding in violence in 1911. This was caused by two very different factors. First, the machinery for establishing the boundaries of the appellation was left to the Ministry of Agriculture, and political opposition was immediate from those growers excluded and the merchants who stood to lose from its creation. Second, the economic conditions in the Marne and the Aube made growers desperate, especially after the poor harvest of 1908 and the nonexistent one of 1910.

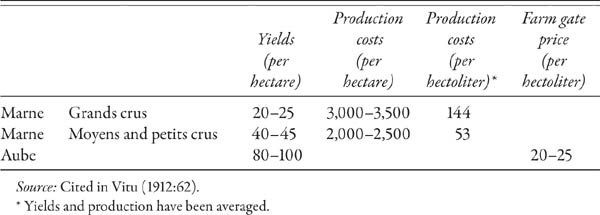

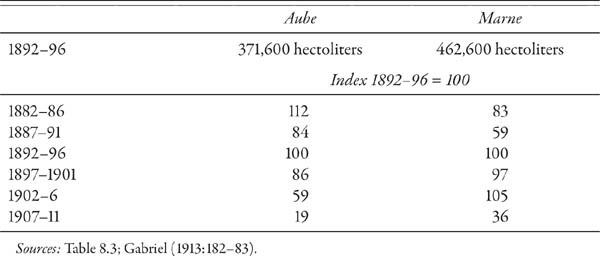

Unlike Bordeaux, there were major disputes over what constituted the natural region of Champagne. The modern department of the Marne contains Épernay and Reims, the two major centers of production, but the old province of Champagne was much more extensive and included almost exactly the present-day departments of Aube, Haut-Marne, and Ardennes. Growers in the Aube were particularly incensed at being excluded from the first boundary proposal, as they claimed they had replanted low-yielding varieties (half pineau and half gamay) after phylloxera to guarantee grape quality to make champagne, and as a result they believed they would be uncompetitive against the high-yielding producers of sparkling white wines in the Loire and elsewhere.72 The Fédération replied that the Aube growers were themselves low-cost producers of inferior wines, as production costs were much higher in the Marne because the greater density of the vines made the use of plows impossible (table 6.4). Given the wide range of wines produced in most French departments it was easy to cite unrepresentative cases, and this seems to have been the case with the Fédération, as average yields in the Marne increased from 24 hectoliters per hectare in the 1890s to 30 hectoliters in the 1900s, while those in the Aube increased from 16 to only 24 hectoliters.73 The real threat from the Aube perhaps lay more in the future, as phylloxera had advanced faster there than in the Marne, so there was the possibility of significantly higher yields after replanting. Yet table 6.5 suggests that only very little wine could have entered the Marne from Aube between 1907 and 1911 because the collapse in its harvest was even greater than in the Marne, leaving growers who had invested heavily in replanting as desperate as their neighbors. The harvest in the Aube in 1910 was just 0.8 percent of what it had been in 1892–96, so it was little wonder that many champagne houses were able to deny that they were buying supplies there. The presence of large number of growers in both departments encouraged a political compromise, and the final decree of June 1911 created two zones, the Marne and L’Aisne, areas which had been initially included in the 1908 proposal, and another including Aube, Haut-Marne, and Seine-et-Marne, whose growers could still sell their grapes to the champagne houses, although this information had to be shown on the bottle.74

TABLE 6.4

Production Costs of Grapes in the Marne and Aube

Although the new regional appellation shifted some power back to the growers, it was less significant than in the Midi or Bordeaux. Producers of quality grapes were always going to find a market because the leading champagne houses needed to create an exclusive product, although many of these took the opportunity provided by phylloxera to integrate backward by buying diseased vineyards cheaply. The voluntary regulations followed by the Syndicat du commerce before 1911 were now extended to all producers, including those selling cheap champagne in the domestic French market. The widespread economic difficulties of growers and the legislation of 1905 provided a political opportunity to restrict the market power of those houses specializing in cheap champagne, but only the creation of cooperatives would allow them to establish some independence from the major, independent champagne houses.

TABLE 6.5

Harvest Size in the Aube and Marne, 1889–1911

Today’s major champagne houses were already established by 1840, and their early success was closely linked to marketing. As first movers, they were able to consolidate their success by product development in the form of “vintage” champagne, and by the second half of the nineteenth century the well-known brands commanded a significant premium. They were more successful than producers in Bordeaux, Jerez, and Porto in controlling the quality of their product. Champagne had to be bottled at source, and, although fraud was a major concern in the late nineteenth century, significant advances had been made by individual firms and the leading champagne producers’ pressure group, the Syndicat du commerce des vins de Champagne, in controlling the illegal use of brand names and the appropriation of the word “champagne” for other sparkling wines in France. The 1889 High Court decision declared that only wines made in the small geographical area of the Marne could be described as champagne, thereby banning the use of champagne as a generic term for sparkling wines in the French market. Legislation also protected the champagne houses from the appropriation of their brands by others. Secure in the knowledge that the legal system would protect their brand, firms such as Moët & Chandon and Perrier-Jouët invested heavily in the making and advertising of their fine wines and developed a sufficient reputation to allow them to sell at higher prices than their competitors did. The wine shortages caused by phylloxera and other diseases after 1900 did not seriously threaten this market. The leading firms not only enjoyed extensive stocks of old wines and could afford not to buy in poor years, but they could charge consumers higher prices due to the scarcity of quality champagne.

A major new market developed among the emerging middle classes, leading to a 50 percent increase in world sales during the 1888s and 1890s, which encouraged new entrants into the industry to supply cheap champagnes.75 With the collapse of local grape production, they were forced to look outside the traditional area of supply, and the bitterness of the events of 1911 can be explained by the desperation of growers in the Marne and the Aube as they faced both disastrous harvests and low prices, at a time when sales were booming.

1 René Crozet (1933), cited in Forbes (1967:150). My calculation—assuming a yield of 20 hectoliters per hectare with no wastage.

2 Paul (1996:198).

3 Loubère (1978); Pan-Montojo (1994).

4 Simon (1934a:116–17).

5 The old, prerevolutionary province of Champagne was split into five departments: Aisne, Aube, Haute-Marne, Marne, and Seine-et-Marne. The major champagne towns are Reims and Épernay.

6 Brennan (1997:44, 53).

7 Faith (1988:25).

8 Simon (1934a:21–22).

9 Paul (1996:204–5).

10 Ibid., 201.

11 By contrast the blending of wines with different qualities to produce a standardized product was regarded as fraud in the eighteenth century. Ibid., 205.

12 Dovaz (1983:18), cited and translated in Paul (1996:206).

13 Brennan (1997:240–46).

14 Loubère (1978:109, 281).

15 Maizière predicted this massive growth in trade in 1846: “sparkling wines have made fortunes for twenty merchants, ensures an honest living for a hundred more, and provide a prompt and profitable outlet for the product of every class of grower; yet the present state of the trade, already ten times as lucrative as the old, is only in its infancy and can multiply tenfold within a few generations.” Maizière (1848), cited in Faith (1988:55).

16 Forbes (1967:322–23).

17 MacCulloch (1816:117), quoted in Simon (1934a:40–41).

18 Forbes (1967, chap. 28) gives a good description of the various processes, on which this is based. Producers also learned to exploit more skilfully the differences in temperature found in their cellars: the warmer areas were used to start the secondary fermentation in the spring, and the cooler parts to slow it down if the bottles started breaking. By the late nineteenth century selected yeasts and sugar were added to help the secondary fermentation.

19 Jullien (1824:18); Moreau-Bérillon (1922:123).

20 Guy (1996:18). Vizetelly (1879:54), reported in the late 1870s that while some houses lost 7 or 8 percent, the figure for some others was less than 3 percent.

21 Le Vigneron Champenois, March 29, 1911.

22 Ibid., July 5, 1908.

23 Opposition centered on René Lamarre, the author of the pamphlet La Révolution champenoise, published in 1890.

24 Forbes (1967:24–25).

25 Vizetelly (1879:25).

26 Ibid., 50.

27 Ibid., 109, 113. The 900 acres (about 550 hectares) of vines provided employment for 800 laborers and vinedressers, a doctor and chemist, which were provided free of charge by the firm, and sick pay and retirement pensions for workers.

28 Simon (1934a:66).

29 Faith (1988:73).

30 Simon (1934a:45).

31 Simon (1905:99, 137). Simon notes that the taste for sweet champagne lasted longer outside London. For example, the shipper George Goulet exported sweet champagne with 16 percent liquor to a merchant in Birmingham, but with only 2 percent to London.

32 Simon (1934a:43, 50).

33 Ibid., 74.

34 Simon (1905:147).

35 Ibid., 146.

36 Ridley’s, June 1909, p. 558.

37 Simpson (2004:99).

38 Faith (1988:68).

39 Ridley’s, August 1893, p. 436. In this case the payment was 4d. a cork. Simon (1934:112–13) argues that four major houses refused to participate in this type of scheme.

40 Ridley’s, December 1890, p. 655.

41 Lamarre, cited in Faith (1988:78).

42 The decline in red wine production released some land, while better control of the secondary fermentation limited wastage.

43 Guy (1996:211). However, Tovey noted in 1870 that “even at Epernay and other places in Champagne it is well known that there are houses which use but little of the wine of the district in the manufacture of their wines” (19).

44 Guy (2003:92).

45 Lheureux (1905:47).

46 Guy (2003:100–101).

47 Rather than unite growers, therefore, the Association syndicale divided them. Lamarre attacked its work from his newspaper, the Révolution Champenoise.

48 Lheureux (1905:55–56); Piard (1937:57).

49 Cited in Guy (2003:110–11).

50 Lheureux (1905:67).

51 Guy (2003:108).

52 Letter of 1903 from growers to the mayor of Épernay, cited in ibid., 110.

53 Le Vigneron Champenois, January 31, 1900.

54 Lheureux (1905:75); Piard (1937:59).

55 Lheureux (1905:92).

56 Le Vigneron Champenois, February 10, 1904. Moët & Chandon had also established its own workshop for grafting. Ibid., July 10, 1904.

57 Piard (1937:66).

58 Le Vigneron Champenois, March 10, 1909.

59 Augé-Laribé, in ibid., March 29, 1911.

60 Bara (1998:172–73).

61 Le Vigneron Champenois, August 13, 1904.

62 Sempé (1898:44).

63 Quoted in Faith (1988:64).

64 Simon (1905:119).

65 Vitu (1912:64).

66 Guy (2003:79).

67 Calculated from Le Vigneron Champenois, June 1, 1910.

68 Allowing for losses in production, this implies sales of 87 bottles per 100 liters of grape juice produced.

69 Guy (2003:122).

70 Ibid.,79. There was logic in Mercier’s action, as the increased import duties on champagne made it uncompetitive in Germany.

71 Ibid., 135, 140.

72 Vitu (1912:58). Pineau is a synonym for the pinot family of grape varieties and better-quality wines, while the gamay is a high-yielding variety.

73 Calculated from Lachiver (1988:598–99, 608–9).

74 Vitu, Délimitations régionales, 36. For the conflicts, see especially Bonal (1994); Faith (1988); Forbes (1967); and Guy (2003).

75 As Henry Vizetelly noted (1879:61): “now-a-days the exhilarating wine graces not merely princely but middle-class dinner-tables, and is the needful adjunct at every petit souper in all the gayer capitals of the world.”