CHAPTER 7

![]()

Port

No wine in the world can produce such a combination of colour, aroma and tastes as a fine vintage port.

—Geoffrey Murat Tait, 1936:46

WINE ACCOUNTED FOR about half of all Portugal’s exports during the nineteenth century, with port assuming by far the greatest share. The best and most expensive was made by British merchants to meet consumer demand in their home market, where it enjoyed a privileged position for at least a century and a half after the signing of the Methuen Treaty in 1703. Port is a fortified wine, produced from grapes grown along the steep valley of the River Douro and blended and matured in the cellars (lodges) of the shippers in Vila Nova da Gaia, opposite Porto in northern Portugal. Increasing the alcoholic content of the wine to 17 or 18 percent makes it microbiologically stable, and brandy was traditionally added before shipping which considerably reduced the risks of damage caused by transportation or as a consequence of poor storage.1 By the mid-eighteenth century, brandy was also added to stop fermentation prematurely, thereby creating a naturally sweet wine. As fortified wines kept longer on opening, port and sherry decanters became a common feature on the sideboards of many middle- and upper-class households during the nineteenth century.

The addition of alcohol in the production of dessert wines influenced the nature of the commodity chain, as not only did it solve the problems associated with making wine in a hot climate, it also offered economies of scale in the preparation of wines for export and marketing.2 Fortified wines were relatively easy to blend to create large batches of house wines with similar characteristics from one year to the next, facilitating the creation of brands, and allowing British retailers to obtain repeat orders that they could then sell under their proprietary name, or communicate shifts in the nature of consumer demand. Shippers consolidated their positions by gaining greater control of the chain and its profits through product development in the form of vintage port, which was a highquality, expensive wine produced only after an exceptional harvest. These factors helped create entry barriers, as potential new competitors in Porto needed both access to large stocks of wine to meet retailers’ demands and their own distribution networks in the British market.

This chapter begins by looking at the development of port wine for the British market, and the geographical separation between grape production in the Douro valley and the maturing and exporting houses in Porto. This is followed by discussion of the development of different types of port wine and how the sector responded to the challenges of the second half of the nineteenth century, namely, the problems of maintaining supplies and product quality during the phylloxera epidemic, and the opportunities and difficulties faced by producers in creating a mass market for cheap ports. Finally, the chapter considers the conflicts between the British exporters and Portuguese growers over regulation and regional appellations from the eighteenth century. Winegrowers in the Douro valley, unlike those who produced sherry in Jerez, enjoyed government support for a regional appellation, while shippers were able to influence negotiations so that the new Anglo-Portuguese Commercial Treaty in 1916 recognized that port and madeira came only from Porto and Madeira.

PORT AND THE BRITISH MARKET

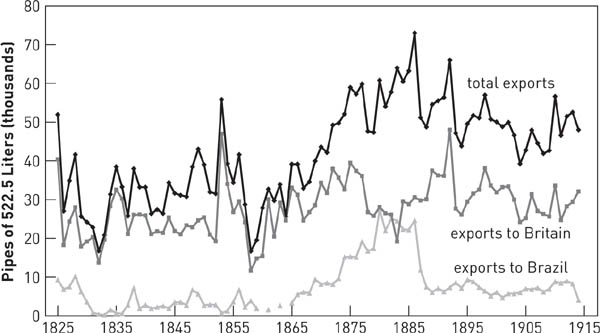

When war broke out with France in the 1690s, the British merchants looked to Portugal for wines, and this trade received a major boost with the Methuen Treaty of 1703. This left duties on Portuguese wines at a maximum of two-thirds of those paid on French wines, in exchange for removal of restrictions on the entry of certain types of woolen cloth. The British market remained by far the most important both in terms of volume and especially value, and port wine accounted for over a third of all Portugal’s exports as late as the 1870s, and still almost a fifth at the turn of the twentieth century (fig. 7.1, table 7.1).

The early exports came from Portugal’s coastal regions, but this wine proved to be too thin and astringent for the British market. By contrast, those from inland along the banks of the River Douro were dark red, the result of a fast and furious fermentation at high temperatures.3 The earliest reference to alcohol being added to port before shipping to avoid it deteriorating was 1678, but by the early 1700s it was also added during fermentation to change taste, and according to Sarah Bradford, the eighteenth century is the story of how the “despised red portugal” was developed into a wine “cherished and revered” by its British consumers.4 The degree of sweetness depends on the amount unfermented saccharine, which in turn is the result of the initial sugar content of the grapes and the moment when the brandy is added. Alcohol was added again to the wine before it was sent down river to mature in Porto, and again prior to export, and even in Britain itself. The amount of brandy varied significantly but increased over time as the nature of the wine changed. The Agricultura das Vinhas, a handbook on viticulture published in 1720, recommended that 13.5 liters of brandy be added to a pipe of about 525 liters to strengthen and improve the wine’s quality. This was insufficient to significantly change the wine’s flavor, and most growers appear to have continued to use less than 25 liters before 1820.5 In the late 1860s A. Girão noted that the better growers used 25–50 liters of brandy per pipe and another 50 to 76 liters after fermentation.6 The historian Norman Bennett writes that before 1914 the quantity of brandy ranged from as little as 5 percent to occasionally over 50 percent, depending on the nature of the original wine must, the price and availability of alcohol, and the type of port being produced.7 The general increase over time reflects the greater skills in wine making and changes in consumer taste. Geoffrey Tait, for example, argues that there was a switch in fashion around the mid-nineteenth century from making dry ports with a complete fermentation to making them stronger and sweeter by arresting fermentation with larger quantities of brandy.8

Figure 7.1. Portuguese exports of port wine. Source: Andrade Martins (1990: Quatro 66)

The addition of brandy allowed wines to last considerably longer without deterioration, but it made them hard and crude so that they had to be matured much longer before they could be drunk. The smaller quantities of alcohol added during most of the eighteenth century resulted in the wine being ready to drink within the year of making, but by the end of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries the average period for maturing port according to the historian A. D. Francis “was creeping up to three years and often more.”9 Certainly John Croft in the late 1780s was drinking wine that had been kept four years in the casks followed by a further two years in bottles, while Henderson in 1824 noted that wines were being kept ten or fifteen years.10

TABLE 7.1

Wine as a Share of Total Portuguese Exports, 1840s–1900s

Grape production and the manufacture of port wine were separated geographically as no other major wine region prior to the railways. The grapes were grown inland, some 100 kilometers up the Douro valley, and the wine was then shipped downriver to the wine lodges of the exportadores in Vila Nova, opposite Porto. The British consul described the wine region in 1884:

The district lies on either side of the River Douro, commences about 60 miles from its mouth at Oporto, and reaches with a varying breadth of from 3 to 15 miles, to the Spanish frontier; that is, for about 27 miles. The soil is a brown, slaty schist, the mountains are lofty and precipitous, and the land is ill-watered; most of the lateral valleys having no more possibility of irrigation than is afforded by a tiny brook, a torrent in winter, and in the height of summer a dry watercourse. Roads, in the true sense of the word, do not exist; and it would be safe to say that no equal portion of the earth’s surface, so rich is agricultural wealth, possesses means of communication so extraordinarily bad: chiefly because no plant but the vine would grow in places so rugged and so inaccessible.11

The steep valleys and the need for terracing made grape production labor intensive, while the vines produced low yields. At the outset of our period there existed a strict separation of functions between wine production, and the subsequent maturing, blending, and exporting of the wines in Porto. The shippers benefited from knowledge and connections in the British market, but they often lacked sufficient capital and local connections in Portugal and were inexperienced at appreciating the potential of young wines.12 In the mid-eighteenth century growers were independent and sold their grapes or wines to local comissários (brokers). Around 1800 these brokers acted for a single shipper and reported on the state of the vintage, prepared and monitored contracts with the growers, and arranged for the transfer of the wines downriver to Porto.13 In this way, exporters were able to overcome their lack of knowledge of viticulture “by exchanging patronage, power, and market access for the judgment and access to social networks possessed by their rural agents.”14 As the century advanced, Porto’s merchants were themselves leasing property and controlling their suppliers more closely in the vineyard and winery.15 Merchants established ties with a few trusted growers, who received loans and supplies of brandy and, in cooperation with the merchant’s representative, followed their advice in wine making.16 Forrester noted in 1852 that the merchants preferred to buy their grapes and make the wine themselves, while by the late nineteenth century some of the best estates, such as Quinta do Zimbro, Quinta da Boa Vista, and Quinta da Roeda, were owned by British merchants.17 Yet fine wine was only one segment of the trade. John Peter Gassiot, a partner of the export house Martinez, Gassiot & Co., noted in 1862 that by buying from these “Portuguese speculators,” “our operations are very simple, and we could carry on a large business with a comparatively moderate amount of capital, because the large trade in this country is not a trade in fine wine, but for good, useful, honest, sound wine—wine that will not turn out bad, but which has no pretensions to be called superlative wine.”18 The role of these houses, as with sherry in Jerez, was absorbed by the exporters over the century, as they integrated backward into wine making and maturing.

Port shippers initially often traded in a wide variety of goods, and between 1727 and 1810 they belonged to the Factory, an institution that acted to protect the collective interests of the British merchants in Portugal. The historian Paul Duguid has shown that the successful export houses in the nineteenth century, in contrast to the previous century, were those that specialized exclusively in port wine.19 Many of the export houses had partners in London, and these collected orders that were forwarded to Porto, thereby providing a supply of information on the shifts in demand for particular types of wine, and a major part of the long-term success of these companies can be explained by their control of the British market. Indeed, leading Porto houses such as Sandeman & Co. and Cockburn & Co. were set up by established wine firms in Britain.20 Without access to a network of retailers, exporters often found that the only outlets for their wines were auctions, where prices were often unpredictable.21

Unlike in Bordeaux, Jerez, or Reims, much of the foreign merchant community did not change their nationality, and intermarriage with the Portuguese was relatively rare. This makes David Ricardo’s choice of the trade in wool and wine between Portugal and England, which has since been repeated ad infinitum in students’ economic textbooks, a surprising example to use in his explanation of comparative advantage.22 First, England could hardly be regarded as a wine producer at this time. Second, writers such as David Hume believed that without the preferential duties, relatively little port would have been drunk in Britain, suggesting that the merchants competed on an unfair playing field.23 Finally, not only did British manufacturers produce the woolen goods to sell in Portugal, but a large number of them also matured the wine from Porto and shipped it to Britain. The gains from trade clearly benefited one side considerably more than the other.

This is certainly what the Portuguese government believed. While it was aware that the British merchants were necessary for exporting the wine (not to mention the political and military support that Britain provided for Portugal in its dealings with Spain and France), it provided a pretext for earlier government intervention in the wine market and to a much greater extent than in either France or Spain. In particular, it created the world’s first regional appellation that attempted to bypass British merchants by exporting wine directly to foreign markets.24

PRODUCT DEVELOPMENT AND THE DEMANDS OF A MASS MARKET

Wine making and blending were highly skilled tasks, and an expert taster allowed a firm to produce ordinary ports with the same characteristics indefinitely.25 Port wine falls into two main categories: wood ports, which are those matured in casks, and vintage ports, which are matured in bottles. Port matures better in bottles than in wood, as the wine’s aroma and color are not lost and a highly desirable crust is deposited. Maturing wines in wooden barrels also involves a financial loss because of evaporation and leakage. Vintage ports consist of a selection of wines from distinct vineyards vatted together after a particularly good year and then kept separate from other wines. Each individual shipper produces distinct wines, has its own opinion as to what constitutes quality, and decides whether to declare a harvest a “vintage,” which would affect the reputation of the house.

Port was traditionally sold under the retailer’s name, and it was the retailer’s reputation and skills that were rewarded with greater sales and profits. The creation of vintage port changed this as it allowed the shippers in Porto, rather than the retailer, to brand the wine. Prior to phylloxera the wine was kept for three years in wood before it was bottled, but it was not drunk for at least another three years, and often as much as fifteen or twenty years or more.26 Wines were shipped in casks to Britain to be bottled and then left in the retailer’s or the customer’s cellar—“well-to-do Farmers” purchased a pipe or two whenever there was a good vintage—thereby pushing the significant costs of storage and ageing “down the supply chain.”27 The local wine merchant was often expected to advance some credit for the purchase and take responsibility for bottling the wine in the consumer’s cellar. However, by the late nineteenth century a combination of agrarian recession and the lack of town cellars in the growing urban sector increased the demand for bottled vintage wines ready for immediate consumption, rather than wines to lay down for several decades.28 Berry Brothers in 1909, for example, advertised not only a number of old house wines, but bottled vintage ports under the shippers’ brands for 1881, 1884, 1887, 1890, 1896, and 1900. The most recent vintage wine that was available was that of 1904, having been bottled in 1906 and produced by five different Porto shippers (Croft, Taylor, Martinez, Warre, and Fonseca).29 Retail merchants required not only considerable capital when dealing with vintage ports, but also the necessary skill to bottle it, although a carefully selected bottled port reputably afforded “their holders far less anxiety as to their sale than do many other Wines which their cellars contain.”30 Few merchants had the capital to carry large stocks of bottled vintage port, and Ridley’s believed in 1894 that there were “no more” than eight Houses with more than “20,000 dozens.”31

The greatest volume of port in Britain, however, comprised wood ports, which arrived for immediate consumption, being sold straight from the barrel in public houses, or bottled. Tawny port differed from vintage port in that it was a blend of wines from a number of years and was matured in the wood for several years. Over time it lost some of its color, hence its name, and was bottled immediately prior to sale. Because of the time it took to make, tawny port was also expensive, but a cheaper version could be achieved by simply mixing red wines with a portion of white.32

Other types included crusted ports which, like vintage ones, were of a particular year but of an inferior quality, and ruby ports, a blended wine that was sold before it had matured into a tawny.33 Classification was complicated and changed over time, as noted by the English writer Henry Vizetelly when he visited Porto in about 1880:

One great disadvantage under which shippers of Port wine labour is the frequent change of fashion with regard to the style of wine demanded in England. So constant are the changes and so endless the varieties now-a-days that it has been said there are almost as many styles of Port wine as shades of ribbon in a haberdasher’s shop. At one time a deep-coloured, heavy wine will be in vogue; at another a wine paler in colour and lighter in body, but rich in favour. Sometimes dry wines are in request, and latterly the fashion has set in for thin wines of a light tawny tint, the result of their resting for many years in the wood—the kind of wines, in fact, which the Oporto shippers invariably drink themselves.34

As Ridley’s noted, “a Wine that takes twenty years in bottle before it is fit for consumption, is scarcely a commercial article,” and attempts were made to shorten the maturing process.35 Supply-side changes helped, as the postphylloxera wines matured quicker, with two instead of three years in the wood becoming the norm and the time required in the bottle shortening, with consequent savings for merchants. As a result, wines from the 1880s and 1890s were reported as to have “come to hand so rapidly” compared with those of the 1860s and 1870s, and “in many cases vintage Wines of the last fifteen years have been able to do duty for what previously required blending for early use.”36

The arrival of phylloxera created shortages of cheap wines in the Douro district, a problem solved in the short term by using those from the southern Portuguese provinces. These wines were traditionally used to make the brandy that was added to port, but they were now exported as port wine itself, which Ridley’s feared risked undermining consumer confidence for fine wines, such as happened with sherry in a classic “lemons” scenario.37

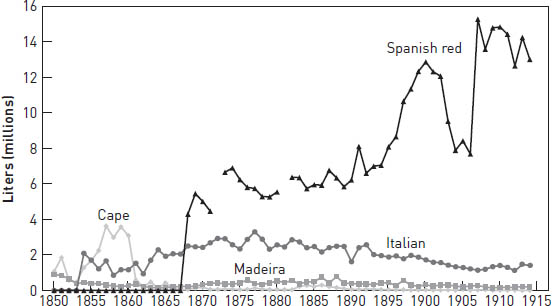

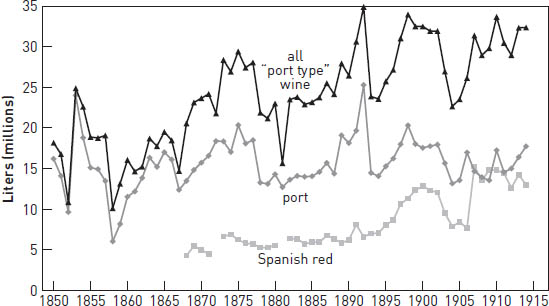

By creating a reputation for fine vintage wines, the leading port shippers were less willing to try to compete in the cheap section of the market where in any case they had no comparative advantage.38 Instead it was the British importers and retailers who looked elsewhere for cheap generic ports, such as Spanish red from Tarragona in southeastern Spain, that could be sold in London for about half the price of young ports of the Douro (figure 4.6). Growers and merchants in this coastal region of Catalonia had for centuries adapted their products to changing demand, whether distilling spirits for the Dutch market, fortified wines for export to the colonial market, or cheap wines for Barcelona.39 British demand, a cheap peseta, and the arrival of phylloxera in Portugal offered growers not only the possibility of exporting red wines to be blended with those from Porto, but also a market for “Tarragona Red,” sold in bottles that became popularly known as the “Big Bob Bottle” (figs. 7.2, 7.3). Prior to the mid-1880s, exports were minimal, but they then grew rapidly, so that in 1896 more Spanish red was imported into Britain than sherry and Spanish white.

The supply of cheap “port wines” from Tarragona could only be met after a number of technical problems in wine production were resolved. In particular, better fermentation methods were required to rid the wine of the earthy flavor and coarseness that so often characterized it.40 One local development was the artificial maturing of bottled wines, called insolation. This was a modification of Pasteur’s system, with direct sunlight being used rather than artificial heat, in a similar fashion to what had been used in Madeira a century earlier. Insolation not only helped prolong the life of the wine but also accelerated the ageing process cheaply. According to the type required, the wine was left in clear, white, glass bottles and exposed for between ten days and a month. The color changed from a “purple tinge” to pass “successively through every shade of ruby, from ruby to rancio, and from rancio to light tawny if left long enough.”41

Figure 7.2. UK imports of generic port wines. Source: Wilson (1940:362–63)

Yet the British demand for Tarragona wines was brief, as exporters failed to maintain the quality of their product in the face of rising prices caused by the devastation of local harvests by phylloxera and the rapid appreciation of the peseta after the conclusion of the Cuban war. Merchants in Tarragona looked for cheaper, and inevitably inferior, Spanish wines to remain competitive. The end result was not unexpected, as “when genuine Tarragona was offered to the Public, it was quick to appreciate it, and the consumption rapidly increased. But when flagons of rubbish, bearing the name Tarragona, were substituted, the discriminating reverted to some more trustworthy beverage.”42 Exports of Spanish red remained strong, especially in the years up to the First World War, but a significant proportion was described as “Basura de Batalla,” namely, rubbish wines produced in Valencia, Alicante, and La Mancha, rather than the “choicest products of the Priorato.”43

Figure 7.3. UK imports of port and Spanish red. Sources: Wilson (1940:362–63) and Ridley’s (various years). All “port type” wine includes port, Spanish red, cape, madeira, and Italian.

RENT SEEKING, FRAUD, AND REGIONAL APPELLATIONS

The creation of the Companhia Geral da Agricultura das Vinhas do Alto Douro in 1756 to control the port wine trade was just one of a number of wide-ranging initiatives by the future Marquês de Pombal to regulate the Portuguese economy. The background to the Companhia was a steep drop in exports and low prices that followed an exchange of correspondence between the British Factory in Porto and the Douro brokers, who mutually blamed each other for adulterating the wine and thereby causing a decline in its reputation.44 This crisis not only affected the Douro growers and the Porto merchant community but also led to a fall in tax revenue for the government and the worsening of the country’s balance of payments. The Companhia was given the power to regulate the production; sales, prices, transportation, storage, and exports of wines and brandy from the Douro region; the distilling and sale of brandy in northern Portugal; and a monopoly on selling wines in public houses in Porto and the surrounding districts, as well as the important export trade to Portugal’s Brazilian colony.45 The area that supplied grapes for port was strictly defined, and wine was divided into four categories: the legal wine, the only kind that could be officially exported to Britain; separado, which was set aside for export to the rest of Europe and Brazil; ramo, a wine that was reserved for local consumption; and refugado, which was used for distillation. According to its statutes, its objectives were “to uphold with the reputation of the wines the culture of the vineyards, and to foster at the same time the trade in the former, establishing a regular price for the advantage alike of those who produce and who trade in them, avoiding on the one hand those high prices which, rendering sales impossible, ruin the stocks, and on the other such low prices as prevent the growers from expending the necessary sum on the cultivation of their vineyards.”46 It was the Companhia tasters who determined what wine could be exported, and the British merchants claimed that the regulations increased costs but not the quality of the wine.

The Companhia was more than just an attempt by a mercantilist state to regulate the country’s leading economic sector, as it was also a joint-stock company whose merchants had important trading privileges associated with the buying and selling of wines in the Douro valley. As such, the original Companhia reflected the interest of a predatory state, as well as acting as a private rent-seeking monopoly and a regional appellation. The Companhia was heavily criticized from the first moment in the British press, which repeated the complaints of its merchants in arguing that it was an institution to create rents and enrich the Portuguese growers and local merchants at their expense.47 However, while the Companhia was not a disinterested regulator, the British merchant community, despite their considerable and consistent protests, perhaps did not suffer unduly.48 The Companhia controlled some of the worst abuses in wine production, and the period between 1781 and 1807 has been described as a “golden age” for port.49 The Companhia helped reinforce a market that was already segmented, so that by around 1840 British companies accounted for about two-thirds of exports to their own domestic market, but only one among the leading ten firms that traded with Brazil, and vineyard ownership by British firms was still negligible.50 The appearance of new exporting houses after the Napoleonic Wars (Sandeman, Martinez, Cockburn, and Grahams) might suggest a changing of the guard took place, as some old, established houses declined, but the port trade in general enjoyed relative stability.51 Likewise, it is probably more correct to see the Companhia not as an attempt by the Portuguese state to protect its citizens against the rapacity of foreign exporters, but rather as a monopoly created by a weak fiscal state that created sinecures for a small domestic elite in exchange for revenues, making it hated as much by other Portuguese citizens as it was by the British merchants.52 Finally, although more of the profits remained in Portuguese hands than would otherwise have been the case, abuses were limited by the fact that port wine was traded internationally and had to compete with other alcoholic beverages in the British market, and by the fact that the Portuguese government depended on the sector for foreign exchange and taxes.

The Companhia’s privileges were abolished in 1834 following the Liberal victory in the 1828–34 civil war but were reestablished once more with a new charter for twenty years in 1838. Its powers were now reduced and wine could be freely sold. Although the Companhia still determined what could be exported, it was also expected to promote wines from outside the region and provide credit to growers. The Companhia continued to act as a trading company after its other privileges were abolished. Between 1852 and 1865 the Comissão Reguladora da Agricultura e Comércio das Vinhas do Alto Douro was created, composed of elected members from the growers and Portuguese merchants. Its powers were limited and proved short-lived, but it represented more closely the interests of the sector, rather than just providing sinecures.53

A new regulatory institution was proposed in the late 1880s, the Real Companhia Vinícola do Norte de Portugal, which one critical trade journal described as being “a body of eight Portuguese gentlemen,” whose “interest in the Port Wine Trade is by no means extensive,” and the Portuguese government.54 The Companhia Vinícola was to receive an annual subsidy equivalent to £3,385 over five years and give a guaranteed 6 percent interest per annum for thirty years to the shareholders, who would provide capital of £450,000. The company was to sell its wines with a certificate of origin and promote them in foreign markets. Once again the British shippers in Porto felt threatened, claiming that as the new company had no stock of its own, it would sell poor-quality young wines under the “Government Arms” and generally discredit the trade. To widen their negotiating base, the British shippers collected the signatures of 2,500 Douro farmers and attracted the backing of the influential periodical O Commerico do Porto.55 Between January 21 and February 3, all but two of the wine lodges closed their doors in protest, and when the unemployed workers and military came into “collision,” as Ridley’s reported, the shippers wrote to the foreign secretary, Lord Salisbury, to demand protection. The Portuguese government for its part reportedly censured all telegraphs leaving Porto to stop news of the events from reaching British newspapers. All the lodges locked out their workers again for eight weeks in May and June with the exception of three, whose premises had to be protected by the municipal guard. The standoff ended only when the government guaranteed that the new company’s mark would carry no implication of origin or quality.56

TABLE 7.2

Demand and Supply for Douro Wine under “Free-Market” Conditions, 1865–1907

Sources of demand |

Sources of supply |

Export markets: Vintage port—United Kingdom Ordinary port and other wines United Kingdom Brazil France Local markets “Consumo” wine Brandy |

Douro valley: Demarcation Outside demarcation Other sources Central and southern Portugal Foreign imports of brandy and alcohol Industrial alcohol |

While Ridley’s accounts are clearly biased in favor of the British shippers and against this group of “eight Portuguese gentlemen,” the reality was that the divisions ran much deeper than simply Anglo-Portuguese rivalry, as the wine industry was suffering from major structural problems. The ending of domestic restrictions in 1865 created what was effectively a free market for wine and brandy in the Douro region, and at the same time Portugal’s new rail network linked the region to wine and brandy producers in other regions.57 Table 7.2 shows in a schematic form the supply and demand for wines under “free trade” conditions that were operating between 1865 and 1907. In addition to British demand for port wine, France and Brazil imported large quantities of poorer quality ones, and cheap wines (consumos) were drunk locally and others used for making brandy to fortify port. Figure 7.1 shows port exports increasing fourfold from the low point in the late 1850s to the mid-1880s. Not only did the local supply of wine in the Douro fail to keep up with this growth, but the destruction caused by phylloxera led to it falling by at least a third between the 1860s and mid-1880s.58

Phylloxera first appeared in 1867 in Sabrosa (Douro), and Sandeman’s agent noted in 1886 that “good genuine port” was very scarce as the greater part of the firm’s best Douro vineyards had been destroyed.59 The high price paid for ordinary wines for local consumption encouraged proprietors in southern Portugal, whose estates had been devastated earlier, to replant with American vines, which, “with a prolific soil and a ready market for the produce,” led to yields “being sensibly increased.” Industrial alcohol was used to fortify the cheaper wines.60 However, the supply of wine in the Upper Douro was also, “somewhat elastic,” as traditionally only a small area of the delimited district was planted with vines, and only a proportion of the wine—less than half—made into port, the rest being used for making brandy or for local consumption.61 High prices now led to these “other wines,” to be “brought into a state of perfection,” helping growers to make up the deficit.62 Fine wine remained in short supply, but as early as 1887 there was a recovery in production of the cheaper ones in the Upper Douro, and the following year the harvest was 25 percent greater.

It was against this background of better harvests that the growers in 1887 formed a new pressure group, the Liga dos lavredores do Douro, and lobbied their government to demand that the “Port” brand be limited exclusively to wines produced in the Douro, and exclude the use of outside wines to make port wine and the brandy used in their production. The shippers feared that their ability to export cheap wines that had been produced outside the Douro, which allowed them to sell competitively outside the British market, would now be ended. They argued that only they were responsible for quality, and that creating “artificial” boundaries to restrict supply would not only exclude them from using some fine wines from outside the delimited area, but encourage growers to plant high-yielding grapes on unsuitable land within it. In addition, they demanded inexpensive brandy to compete with cheap generic ports in the British market, which could not be obtained in the Douro itself.

On February 5, 1906, a committee appointed by the government, representing growers and shippers, met to consider the problem. A proposed new law created a new delimitation, but this increased the Douro district from 40,000 to 600,000 hectares. It was almost immediately reduced to about 200,000 hectares, “to something like that given by Baron Forrester’s Map.”63 To placate southern growers, brandy for fortifying wines could not be produced in the Douro district.64 Only wines from this Douro appellation could now be sold as port in Portugal, but this did not protect the collective brand in foreign markets. As one “experienced” shipper noted, if southern wines were not allowed to come north, they would be shipped directly from Lisbon, as they had been in the eighteenth century.65

The Anglo-Portuguese Commercial Treaty of 1914, which allowed Britain to trade on most-favored-nation terms in exchange for restricting the use of the names “port” and “madeira” to all Portuguese wines, threatened to open the floodgates of large quantities of Lisbon wines being exported as port. The Douro growers rose in rebellion and troops appeared on the streets once more, leaving fourteen laborers killed and another twenty injured in Lamego.66 When the treaty was finally signed in 1916, the controversial clause 6 was amended to make it illegal to sell in Britain any port or madeira that had not come from Portugal and Madeira respectively, and these wines had also to be accompanied by a certificate issued by the “Competent Portuguese Authorities.” Consequently only wine produced in the designated area of the Douro could use the name ‘port’ in both the Portuguese and British markets. This gave the Douro growers a greater measure of protection than was achieved in any wine-producing nation and led André Simon to claim that “this Anglo-Portuguese Treaty is quite as important, if not more, as the famous Methuen Treaty of 1703.”67

Both port and sherry were traditionally produced for the British market, and despite attempts at diversification, the demands of this market were the key to regional prosperity until late in the twentieth century. Fine wines were expensive to produce, and shippers naturally wanted to participate also in the growing British market for cheap wines after 1860. In theory the demand for cheap wines could be met domestically, with the wines exported by the traditional houses in Porto and Jerez, or they could be imported from other wine-growing regions by merchants based in Britain. The port shippers found it harder than those in Jerez to outsource cheap substitutes themselves, both because there were relatively few regions in Portugal that were able to provide a sufficient supply of wines at a price that might have been acceptable to the British consumer and because of local grower opposition. As a result, it was the British retailers who made “port” cheaper by blending it with generic wines from places such as Tarragona, while the sherry houses themselves competed strongly in the British market with cheap substitutes. Product innovation in Porto involved the creation of vintage port, which gave shippers a major incentive to invest in private brands. While Cockburn, Martinez, or Sandeman might not have been household names, they had a reputation as suppliers of fine vintage ports and consequently were much less interested in selling cheap wines that might damage their brand.

A major peculiarity of the port commodity chain was the nationality of the shippers, which gave the local growers greater influence over the industry than might otherwise have been expected. This resulted in a number of attempts to regulate trade by limiting the freedom of foreign shippers through intervention and regional appellations. Initially, this was simply the concession of a monopoly by the government to a small number of favored individuals in exchange for tax revenue. However, by the late nineteenth century regional appellations were seen as a means of creating a wider distribution of wealth and benefiting the numerous Portuguese growers. By contrast, the British shippers found it much easier to engage with their own government to obtain privileges under the guise of the Anglo-Portuguese alliance or turn to the Foreign Office for help in their relations with the Portuguese government, such as in 1889.

1 Amerine and Singleton (1977:150); Tait (1936:33–36). Wines could still spoil, and Tait noted that “it is necessary to emphasise the importance of keeping casks and vats quite full. This is too little understood in Great Britain, with the result that even if the wines do not actually ‘go wrong,’ they become ‘flat,’ woody, and out of condition.”

2 Economies of scale were also found in distilling to make the spirits and brandy required in the production and strengthening of wines.

3 Robinson (2006:540).

4 Tait (1936:33); Bradford (1969:43).

5 Martins Pereira and Almeida (1999:37), cited in Bennett (2005:40).

6 Bennett (2005:41).

7 Ibid., 27, 41. The availability and price of brandy was at times crucial, and on occasion the wine had to be fermented without any being added at all.

8 Tait (1936:81–82).

9 Francis (1972:260).

10 Bradford (1969:56).

11 United Kingdom Consular Reports (1884), no. 79, p. 112. Report by Consul Crawford.

12 Duguid (2005b:515). For sherry, see chapter 8.

13 Bennett (1990:226).

14 Duguid (2005a:463).

15 Vizetelly (1880); Duguid (2005b:525).

16 Bennett (1994:254).

17 United Kingdom. Parliamentary Papers (1852), Forrester, p. 25; The Times, October 4, 1899. Offley & Co. took a lease on the Quinta da Boa Vista as early as the 1830s and bought it in 1866 and the Cachucha Quinta in 1889. Croft bought the Quinta da Roeda in 1889. Bennett (1994); Duguid (2005b:525).

18 Shaw (1864:177).

19 Duguid (2005b:510–11). Warre & Co., for example, one of the leading eighteenth-century houses that traded in a variety of commodities, including wine, saw its annual exports fall from 2,423 pipes in 1792–1801 to 370 pipes in 1832–40.

20 Ibid., 517.

21 Ridley’s, although not an impartial observer, noted that “we have frequently alluded to what we consider the futility on the part of Portuguese Growers at attempting to create a Market for their Wines by consigning them to Public sale on this side.” It continued that “shippers knew the tastes of consumers, growers did not” (December 1909, p. 1066).

22 The theory of comparative advantage appears to have been first proposed by Robert Torres in 1815 (O’Brien 2004:210).

23 Hume (1752:88).

24 There were earlier ones in Tuscany in 1716 and Tokay in 1737, but these lacked the regulatory bodies that existed in the Douro (Moreira 1998:31).

25 Tait (1936:61–63). Tait argued that a “good taster can easily make a firm, just as a poor one can mar it.”

26 Ridley’s, September 1894, p. 530, suggested three years at least. The time depended on the quality of the vintage. Simon (1934b:87) noted, for example, that wines from 1896 were “now at the top of their form.”

27 Ridley’s, November 1905, p. 130. Duguid (2003:437). Exports to Britain in bottles were described as ‘infinitesimal.” United Kingdom Consular Reports (1893), no. 304, p. 7. An agreement by the Port Wine Shippers in 1907 required that all vintage port be shipped within seven years of the date of the quoted vintage (Ridley’s, February 1907, p.100).

28 Ibid., September 1904, p. 639.

29 See appendix 2.A.5.

30 Ridley’s, September 1894, p. 530.

31 Ibid. In total Ridleys suggest that there were “upwards of 750,000 dozens of Wine of this description in London alone,” but that the “industry is divided amongst a great many hands, most of whom, however, are what are known in the Trade as ‘old-fashioned’ Merchants.”

32 Simon (1934b:9–10); Ridley’s, September 1894, pp. 531–32; January 1900, p. 53.

33 Simon (1934b:10) writes that “Ruby Ports are to Tawny Ports what Crusted Ports are to Vintage Ports: first cousins, but not poor relations.”

34 Vizetelly (1880:145).

35 Ridley’s, September 12, 1894, p. 531. The report continues:

a Wine which, with three years or so in bottle, will show age and bottle character, and at the same time leave a profit if sold about the limit of 30s, is within the reach of all. During the last few years, many attempts have been made to displace bottled Wines with colour, by tawny Wines from the wood, many of which, with age have especial merit.

36 Ibid., 530. The report continues, noting that “without in any way decrying the value of old tawny Wines, we believe that their merit is for Lodge purposes, and not for direct consumption, and we should be sorry indeed to see the day when lightness took the place of colour in popular demand” (532).

37 However, although the leading shippers might be sans reproche,

once let the idea get abroad that the quality of Port Wine is going down, and past experience tells us what will be the result. Those whose vinous education is sufficient to give power of discrimination will of course not be effected—knowing that the Shipping Houses in whom they have been accustomed to trust may still be relied upon. But with that class of consumer who knows Port only as Port, and to whom such names as Sandeman, Martinez, Cockburn, Silva and the rest, convey no meaning, the result in the end is inevitable.

Ibid., March 12, 1888, pp. 133–34.

38 During the phylloxera epidemic, however, Ridley’s (January 1882, pp. 6–7) noted that “too much” cheap wine from southern Portugal was exported as port, and “one of the best known and oldest established firms at Oporto” sold “as a specimen of ‘Port Wine’ a lot that was described ‘as bad as anything ever so misdescribed.’ ”

39 Vilar (1962).

40 Ridley’s, January 1897, p. 9; Roos (1900:208–9).

41 Ridley’s, January 1900, pp. 114–15.

42 Ibid., August 1901, p. 556). Five years later Ridley’s noted that

the consumption of Tarragona Wine in the British markets have considerably declined since Importers decided to neglect the genuine product for a blend which was cheaper. Not only have the distribution of the “Big Bob Bottle” brought an honest Wine into disrepute and crippled a lucrative brand of their trade, but their example has engendered the production of a still baser type. The cheapeners filled their bottles with Wine which was certainly not legitimate Tarragona, and their pupils and followers are now selling a composition which is not even legitimate wine (November 1906, p. 928).

43 Ibid., June 1900, p. 395.

44 Tait (1936:74); Francis (1972:195, 202–5); and Shaw (1998:142–43).

45 Moreira (1998, chap. 2); Duguid and Lopes (2001:4); and Tait (1936:77).

46 Cited in Vizetelly (1880:105).

47 The protests by local tavern owners and growers excluded from the appellation were brutally suppressed in 1757 (Barros Cardoso 1996).

48 Duguid and Lopes (1999:88).

49 Croft (1788); Bennett (1990).

50 Duguid and Lopes (2001:14, 15, 19).

51 Duguid (2005b).

52 Bennett (2005:30–31).

53 This paragraph is based on Moreira (1998, chap. 2).

54 Ridley’s, February 1889, p. 91.

55 Ibid., March 1889, pp. 148–49. See Cockburn (1945:25).

56 Ridley’s, May 1889, pp. 255–56; June 1889, p. 309; July 1889, p. 352. The lodges of Martinez Gassiot and the two Sandeman firms remained open.

57 Bennett (2005:90).

58 Andrade Martins (1991:656).

59 Cited in Bennett (1994:273).

60 Ridley’s, December 1894, p. 698.

61 Tait (1936:16).

62 Ridley’s, March 1889, p. 149.

63 Ibid., January 1909, p. 17; Tait (1936:84–85).

64 Ibid., June 1907, p. 434.

65 Tait (1936:85).

66 Ridley’s, August 1915, p. 530.

67 Simon (1920:250).