CHAPTER 1

Prices, Discount Factors, and Arbitrage

This chapter begins by introducing the cash flows of fixed‐rate, government coupon bonds. It shows that prices of these bonds can be used to extract discount factors, which are the market prices of one unit of currency to be received on various dates in the future.

Relying on a principle known as the law of one price, discount factors extracted from a particular group of bonds can be used to price bonds that are not part of that original group. Furthermore, a particularly persuasive relative pricing methodology, known as arbitrage pricing, turns out to be mathematically identical to pricing with discount factors. Hence, discounting can rightly be used and regarded as shorthand for arbitrage pricing.

Market prices on a single, fixed date are used to illustrate that the law of one price and arbitrage pricing describe the US Treasury market relatively well, but not perfectly. Bonds are not commodities: their prices reflect supply and demand characteristics that are not fully captured by their scheduled cash flows. The US Treasury's Separate Trading of Registered Interest and Principal of Securities (STRIPS) are introduced next, both as a topic of independent interest and as an additional illustration of the complex realities of pricing in bond markets.

The chapter concludes with accrued interest and day‐count conventions, which are used throughout fixed income markets and throughout this book.

For clarity of exposition, prices and examples in this chapter are all as of the close of business on Friday, May 14, 2021. Also, because transactions in the US Treasury market typically settle “T+1,” that is, bonds and cash are exchanged one business day after the trade date, all trades in the examples settle on Monday, May 17, 2021.

1.1 GOVERNMENT COUPON BONDS

The cash flows from government coupon bonds are defined by coupon rate; maturity date; and, synonymously, face amount, principal amount, or par value. For example, in May 2014 the US Treasury sold a bond with a coupon rate of 2.5% and a maturity date of May 15, 2024. Purchasing $1 million face amount of these “2.5s of 05/15/2024” entitles the buyer, as of settlement in mid‐May 2021, to the schedule of payments depicted in Table 1.1. More specifically, the Treasury promises to make a coupon payment every six months equal to half the bond's annual coupon rate of 2.5% times the face amount, that is, ![]() . Finally, on the maturity date of May 15, 2024, in addition to the coupon payment on that date, the Treasury promises to pay the bond's face amount of $1,000,000.1

. Finally, on the maturity date of May 15, 2024, in addition to the coupon payment on that date, the Treasury promises to pay the bond's face amount of $1,000,000.1

This chapter restricts attention to US Treasury bonds, but the analytics presented here apply easily to bonds issued by other countries, because cash flows across sovereign bonds differ mostly with respect to the frequency of coupon payments. Government bonds in France and Germany, for example, make annual coupon payments, while those in Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom pay semiannually, as in the United States.

Returning to the US Treasury market, Table 1.2 reports the prices of selected US Treasury bonds as of May 14, 2021. Per market convention, bond prices are always quoted per 100 face amount. Also, each price in the table is a full or invoice ask price, that is, the total price at which traders stand ready to sell that particular bond. (The division of full price into a flat or quoted price and accrued interest will be explained later in the chapter.) From the third row of the table, then, for example, purchasing the 1.625s of 11/15/2022 costs 102.2862 per 100 face amount or $102,286,200 for $100,000,000 face amount.

TABLE 1.1 Cash Flows of $1 Million Face Amount of the 2.5s of 05/15/2024. Entries Are in Dollars.

| Date | Coupon Payment | Principal Payment |

|---|---|---|

| 11/15/2021 | 12,500 | |

| 05/15/2022 | 12,500 | |

| 11/15/2022 | 12,500 | |

| 05/15/2023 | 12,500 | |

| 11/15/2023 | 12,500 | |

| 05/15/2024 | 12,500 | 1,000,000 |

TABLE 1.2 Prices of Selected US Treasury Bonds Maturing on November 15 or May 15 of a Given Year, as of May 14, 2021. Coupons Are in Percent.

| Coupon | Maturity | Price |

|---|---|---|

| 2.875 | 11/15/2021 | 101.4297 |

| 2.125 | 05/15/2022 | 102.0662 |

| 1.625 | 11/15/2022 | 102.2862 |

| 0.125 | 05/15/2023 | 99.9538 |

| 0.250 | 11/15/2023 | 100.0795 |

| 0.250 | 05/15/2024 | 99.7670 |

| 2.250 | 11/15/2024 | 106.3091 |

The bonds in Table 1.2 are selected from the broader list of US Treasuries for two reasons. First, it is convenient for the computations in the next section that bonds mature in approximate six‐month intervals. Second, when two or more Treasury bonds mature on a given date, the most recently issued bond is chosen because it is likely to be more liquid and, consequently, its quoted price more reliable. For example, the 0.25s of 05/15/2024, which were issued in 2021, are chosen over the 2.5s of 05/15/2024, which were featured in Table 1.1 and issued in 2014.

1.2 DISCOUNT FACTORS

The discount factor for a particular term gives the value today, or the present value, of one unit of currency to be received at the end of that term. Denote the discount factor for ![]() years by

years by ![]() . Then, for example, if

. Then, for example, if ![]() , the present value of $1 to be received in three years is 99 cents.

, the present value of $1 to be received in three years is 99 cents.

Because Treasury bonds promise future cash flows, discount factors can be extracted from Treasury bond prices. In fact, the rows of Table 1.2 can be used to write equations that relate bond prices to discount factors. Starting with the first row of the table, that is, with the bond maturing in six months,

In words, the price of the 2.875s of 11/15/2021 equals the present value of its future cash flows, or, more precisely, the sum of its principal and coupon cash flows multiplied by the discount factor for funds to be received in six months. Solving, ![]() .2

.2

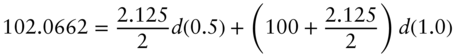

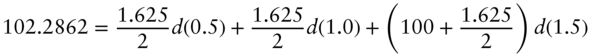

By the same reasoning, the equations relating prices to discount factors can be written for the other bonds in Table 1.2. For the next two bonds, which mature in one year and in 1.5 years, respectively,

Given the solution for ![]() , from Equation (1.1), Equation (1.2) can be solved for

, from Equation (1.1), Equation (1.2) can be solved for ![]() . Then, given the solutions for both

. Then, given the solutions for both ![]() and

and ![]() , Equation (1.3) can be solved for

, Equation (1.3) can be solved for ![]() . Continuing in this way through the rows of Table 1.2 solves for the discount factors, in six‐month intervals, out to three and one‐half years. Table 1.3 reports these results. That these discount factors fall as term increases reflects the time value of money: the longer a payment of $1 is delayed, the less it is worth today.3

. Continuing in this way through the rows of Table 1.2 solves for the discount factors, in six‐month intervals, out to three and one‐half years. Table 1.3 reports these results. That these discount factors fall as term increases reflects the time value of money: the longer a payment of $1 is delayed, the less it is worth today.3

Figure 1.1 shows discount factors, in six‐month intervals, from the bonds listed in Table 1.2 and other bonds, not shown here, which have maturity dates on November 15 and May 15 out to 10 years. Discount factors can again be seen to decrease with term, with the value of $1 to be received in 10 years worth less than 85 cents as of the pricing date.

TABLE 1.3 Discount Factors Derived from Bonds Listed in Table 1.2.

| Term | Discount Factor |

|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.999923 |

| 1.0 | 0.999419 |

| 1.5 | 0.998504 |

| 2.0 | 0.997041 |

| 2.5 | 0.994558 |

| 3.0 | 0.990195 |

| 3.5 | 0.984742 |

FIGURE 1.1 Discount Factors Derived from Selected US Treasury Bonds, as of May 14, 2021.

1.3 THE LAW OF ONE PRICE

The US Treasury 1.75s of 05/15/2022 mature in mid‐May, approximately one year from the settlement date of the examples of this chapter but are not included among the bonds in Table 1.2. How should the 1.75s of 05/15/2022 be priced? A natural answer is to apply the discount factors of Table 1.3 even though the 1.75s of 05/15/2022 are not used to construct those discount factors. After all, because all of these bonds are obligations of the US Treasury, it seems reasonable to assume as a first approximation that the present value of receiving $1 from the Treasury on some future date does not depend on which particular bond pays that $1. This reasoning is known as the law of one price: absent confounding factors (e.g., liquidity, financing, taxes, credit risk), identical cash flows should sell for the same price.

According to the law of one price, then, the price of the 1.75s of 05/15/2022 should be,

where the bond's present value is calculated as the sum of each cash flow multiplied by its corresponding discount factor from Table 1.3. As it turns out, the market price of this bond is 101.693, which is nearly equal to the prediction of the law of one price in Equation (1.4).

Table 1.4 compares market prices with present values for all US Treasury bonds that mature on November 15 or May 15 out to November 15, 2024. The “Present Value” column is computed along the lines of Equation (1.4), giving the prices of the bonds as predicted by the law of one price. The column “Rich (+) / Cheap (![]() )” is the difference between the market price and the present value. Bonds with prices greater than that predicted by a model, like the law of one price, are said to be trading rich, while bonds with prices less than predicted by the model are said to be trading cheap.

)” is the difference between the market price and the present value. Bonds with prices greater than that predicted by a model, like the law of one price, are said to be trading rich, while bonds with prices less than predicted by the model are said to be trading cheap.

TABLE 1.4 Treasury Bond Prices Versus Present Values Using the Discount Factors of Table 1.3. Bonds in Bold Are Used to Derive those Discount Factors. Coupons Are in Percent.

| Term | Coupon | Maturity | Market Price | Present Value | Rich(+)/Cheap( | Issue Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 2.875 | 11/15/2021 | 101.4297 | 101.4297 | 0.0000 | 11/15/2018 |

| 0.5 | 2.000 | 11/15/2021 | 100.9952 | 100.9922 | 0.0030 | 11/15/2011 |

| 0.5 | 8.000 | 11/15/2021 | 104.0904 | 103.9920 | 0.0984 | 11/15/1991 |

| 1.0 | 2.125 | 05/15/2022 | 102.0662 | 102.0662 | 0.0000 | 05/15/2019 |

| 1.0 | 1.750 | 05/15/2022 | 101.6931 | 101.6914 | 0.0017 | 05/15/2012 |

| 1.5 | 1.625 | 11/15/2022 | 102.2862 | 102.2862 | 0.0000 | 11/15/2012 |

| 1.5 | 7.625 | 11/15/2022 | 111.3969 | 111.2797 | 0.1172 | 11/16/1992 |

| 2.0 | 0.125 | 05/15/2023 | 99.9538 | 99.9538 | 0.0000 | 05/15/2020 |

| 2.0 | 1.750 | 5/15/2023 | 103.1970 | 103.1997 | 05/15/2013 | |

| 2.5 | 0.250 | 11/15/2023 | 100.0795 | 100.0795 | 0.0000 | 11/16/2020 |

| 2.5 | 2.750 | 11/15/2023 | 106.3040 | 106.3163 | 11/15/2013 | |

| 3.0 | 0.250 | 05/15/2024 | 99.7670 | 99.7670 | 0.0000 | 05/17/2021 |

| 3.0 | 2.500 | 05/15/2024 | 106.5448 | 106.4941 | 0.0508 | 05/15/2014 |

| 3.5 | 2.250 | 11/15/2024 | 106.3091 | 106.3091 | 0.0000 | 11/17/2014 |

| 3.5 | 7.500 | 11/15/2024 | 124.8220 | 124.5906 | 0.2314 | 08/15/1994 |

The bonds in bold in Table 1.4 are those listed in Table 1.2 and used to compute the discount factors in Table 1.3. Therefore, these bonds are fair, that is, neither rich nor cheap, relative to those discount factors. The prices of the other bonds in Table 1.4, however, can be either rich or cheap relative to those discount factors or, equivalently, relative to the prices of the bonds in bold.

The table, as a whole, more or less supports the law of one price. Most of the deviations of present values from market prices are very small, and even the largest deviation, the 23‐cent richness of the 7.5s of 11/15/2024, is less than 0.2% of the bond's market price.

Across the bonds in Table 1.4, those with the largest deviations are the older, high‐coupon bonds, for example, the 8s of 11/15/2021, issued in 1991; and the 7.625s of 11/15/2022, issued in 1992. Furthermore, these bonds all trade rich relative to the bonds in bold. This is somewhat surprising because, historically, older bonds, which tend to be relatively illiquid, have tended to trade cheap relative to other bonds. Perhaps in the current, low‐rate environment, some investors have a strong preference for income and are willing to pay more than fair value for bonds paying high coupons.

While the law of one price is generally supported by Table 1.4, it is natural to ask whether a trader or investor could profit by buying cheap bonds and simultaneously selling fairly priced bonds; by selling rich bonds and simultaneously buying fairly prices bonds; or – so as to profit on both sides of the trade – by buying cheap bonds and simultaneously selling rich bonds. The next section addresses this question.

1.4 ARBITRAGE AND THE LAW OF ONE PRICE

While the law of one price is intuitive, its real justification rests on a stronger foundation. It turns out that a deviation from the law of one price implies the existence of an arbitrage opportunity, that is, a trade that generates profit without any chance of losing money.4 But because arbitrageurs would flock toward any such trade, market prices can be expected to adjust quickly so as to rule out any significant deviations from the law of one price. Put another way, arbitrage activity can be expected to enforce the law of one price.

To make this argument more concrete, consider an arbitrage trade based on the richness of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022, as reported in Table 1.4. More specifically, sell or short5 the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 and simultaneously buy a portfolio of bonds, from among the bonds in bold in Table 1.4, which perfectly replicates the cash flows of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022. Because the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 are rich relative to the bonds in bold, selling the former and buying a portfolio of the latter, in a way that generates no future cash flows, should generate a riskless profit. Table 1.5 describes this replicating portfolio and this arbitrage trade in more detail.

Columns (2) through (4) of Table 1.5 correspond to the three bonds chosen from Table 1.2 to construct the replicating portfolio. Row (iii) gives the face amount of each bond in the replicating portfolio, that is, the portfolio is long about 2.90 face amount of the 2.875s of 11/15/2021; about 2.94 of the 2.125s of 05/15/2022; and about 102.98 of the 1.625s of 11/15/2022. Rows (iv) through (vi) show the cash flows from those face amounts of each bond. For example, 102.97582 face amount of the 1.625s of 11/15/2022 generates coupon payments of ![]() on November 15, 2021, and on May 15, 2022, and coupon plus principal payments of

on November 15, 2021, and on May 15, 2022, and coupon plus principal payments of ![]() on November 15, 2022. Row (vii) gives the price of each of the bonds, simply copied from Table 1.2, and row (viii) gives the cost of purchasing the face amount of each bond given in row (iii). As an example of the latter, the cost of purchasing 2.94454 face amount of the 2.125s of 05/15/2022 at a price of 102.0662 (per 100 face amount) is

on November 15, 2022. Row (vii) gives the price of each of the bonds, simply copied from Table 1.2, and row (viii) gives the cost of purchasing the face amount of each bond given in row (iii). As an example of the latter, the cost of purchasing 2.94454 face amount of the 2.125s of 05/15/2022 at a price of 102.0662 (per 100 face amount) is ![]() .

.

TABLE 1.5 An Arbitrage Trade: Selling the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 and Buying a Replicating Portfolio from Bonds in Table 1.2. Coupons Are in Percent.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replicating Portfolio | |||||

| (i) | Coupon | 2.875 | 2.125 | 1.625 | 7.625 |

| (ii) | Maturity | 11/15/2021 | 05/15/2022 | 11/15/2022 | 11/15/2022 |

| (iii) | Face | 2.90281 | 2.94454 | 102.97582 | 100 |

| Date | Cash Flows | ||||

| (iv) | 11/15/2021 | 2.94454 | 0.03129 | 0.83668 | 3.8125 |

| (v) | 05/15/2022 | 2.97583 | 0.83668 | 3.8125 | |

| (vi) | 11/15/2022 | 103.8125 | 103.8125 | ||

| (vii) | Price | 101.4297 | 102.0662 | 102.2862 | 111.3969 |

| (viii) | Cost | 2.94431 | 3.00538 | 105.33005 | 111.3969 |

| (ix) | Total Cost | 111.2797 | 111.3969 | ||

| (x) | Net Proceeds | ||||

Column (5) of Table 1.5 gives details of the rich bond to be sold, namely, the 7.625s of 11/15/2022. Its cash flows on the three payment dates are given in rows (iv) through (vi). And, most importantly, note that the sums of the cash flows of the three replicating bonds for each date equal the cash flows of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022. More specifically, ![]() ;

; ![]() ; and trivially,

; and trivially, ![]() . Hence, the replicating portfolio, as defined by the three bonds and their respective face amounts in row (iii), do indeed replicate the cash flows of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022. Section A1.1 in the appendix to this chapter shows how to derive the face amounts of the bonds in this or any such replicating portfolio.

. Hence, the replicating portfolio, as defined by the three bonds and their respective face amounts in row (iii), do indeed replicate the cash flows of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022. Section A1.1 in the appendix to this chapter shows how to derive the face amounts of the bonds in this or any such replicating portfolio.

The discussion now returns to the arbitrage trade. According to row (ix) of Table 1.5, an arbitrageur can sell 100 face amount of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 for 111.3969 and buy the replicating portfolio for 111.2797, which is just the sum of the costs of the three bond positions given in row (viii). The net proceeds of this trade, given in row (x), is 0.1172, or about 12 cents. But, by definition of the replicating portfolio, this trade will neither generate nor require cash on any of the three future payment dates. Hence, through this trade, the arbitrageur receives 12 cents today without incurring any future obligations. While these proceeds may seem small, the trade described in Table 1.5 can, at least in theory, be scaled up dramatically. For example, selling $500 million of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 and buying the appropriately sized replicating portfolio would generate a riskless profit of ![]() .

.

As discussed at the start of this section, if a riskless and profitable trade like the one just described were readily available, arbitrageurs would collectively rush to do the trade and, in so doing, force prices to relative levels that admit no further arbitrage opportunities. In the present example, arbitrageurs would drive the price of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 lower and the price of the replicating portfolio higher until the two were equal.

The crucial link between arbitrage and the law of one price can now be explained. The total cost of the replicating portfolio, 111.2797, given in row (ix) of Table 1.5, exactly equals the present value of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 as reported in Table 1.4. In other words, exactly the same value for the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 is computed through the law of one price (i.e., applying discount factors derived from the prices of bonds in the replicating portfolio) and through arbitrage pricing (i.e., finding the price of the replicating portfolio). This is not a coincidence. Section A1.2 in the appendix proves that these two pricing methodologies are mathematically identical. Hence, applying the law of one price, that is, pricing with discount factors, is identical to relying on the activity of arbitrageurs to eliminate relative mispricings. Put another way, discounting cash flows can be justifiably regarded as shorthand for the more complex and persuasive arbitrage pricing methodology.

Despite the theory, of course, as of mid‐May 2021, the market price of the 7.625s of 11/15/2022 is quoted at about 12 cents more than the value of the replicating portfolio. This can be attributed to one or a combination of factors. First, there are transaction costs in doing arbitrage trades that could significantly lower or even wipe out any arbitrage profit. In particular, all of the prices in this chapter are ask prices, whereas, in reality, an arbitrageur might have to buy bonds at ask prices but sell other bonds at lower bid prices. Second, transaction costs in the financing markets (see Chapter 10), which are incurred when borrowing money to buy bonds and when borrowing bonds to short them, might similarly overwhelm any arbitrage profit. Third, it is only in theory that US Treasury bonds are commodities, that is, fungible collections of cash flows. In reality, bonds have idiosyncratic characteristics that manifest themselves in prices. The discussion of Table 1.4 mentions the richness of older, high‐coupon bonds, and the next section will show idiosyncratic differences in the pricing of Treasury STRIPS.

1.5 APPLICATION: IDIOSYNCRATIC PRICING OF TREASURY STRIPS

In contrast to coupon bonds that make payments every six months, zero coupon bonds make no payments until maturity. Zero coupon bonds issued by the US Treasury are called STRIPS. For example, $1,000,000 face amount of STRIPS maturing on May 15, 2030, promises only one payment: $1,000,000 on that date. STRIPS are created when a particular coupon bond is delivered to the Treasury in exchange for claims on its future coupon and principal components. Table 1.6 illustrates the stripping of $1,000,000 face amount of the 0.625s of 05/15/2030. As of mid‐May 2021, the bond has nine years remaining to maturity, which means it will make 18 coupon payments, from November 15, 2021, to May 15, 2030, and one principal payment, on May 15, 2030. STRIPS received in exchange for coupon (interest) payments are called TINTs, INTs, or C‐STRIPS, while STRIPS received in exchange for principal payments are called TPs, Ps, or P‐STRIPS. Table 1.6 shows that stripping $1,000,000 face amount of the 0.625s of 05/15/2030 generates ![]() face amount of C‐STRIPS maturing on each coupon payment date and $1,000,000 face amount of P‐STRIPS maturing on the bond's maturity date.

face amount of C‐STRIPS maturing on each coupon payment date and $1,000,000 face amount of P‐STRIPS maturing on the bond's maturity date.

The Treasury not only creates STRIPS but retires them as well. For example, upon delivery of all of the STRIPS in Table 1.6, the Treasury would reconstitute the $1,000,000 face amount of the 0.625s of 05/15/2030. It is critical to note, however, that C‐STRIPS are fungible while P‐STRIPS are not. When reconstituting a bond, any C‐STRIPS maturing on a particular date may be applied toward the coupon payment of that bond on that date. By contrast, only P‐STRIPS that were stripped from a particular bond may be used to reconstitute the principal payment of that bond.6 This feature of the STRIPS program implies that P‐STRIPS, and not C‐STRIPS, are likely to inherit the cheapness or richness of the bonds from which they are stripped.

TABLE 1.6 STRIPS Created from $1 Million Face Amount of the 0.625s of 05/15/2030, as of Mid‐May 2021. Entries Are in Dollars.

| Date | C‐STRIP Face Amount | P‐STRIP Face Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 11/15/2021 | 3,125 | |

| 05/15/2022 | 3,125 | |

| 11/15/2022 | 3,125 | |

| … | … | |

| 05/15/2029 | 3,125 | |

| 11/15/2029 | 3,125 | |

| 05/15/2030 | 3,125 | 1,000,000 |

STRIPS prices are essentially discount factors. If the price of C‐STRIPS maturing on May 15, 2030, is 85.9453 per 100 face amount, then the implied discount factor to that date is 0.859453.

As of mid‐May 2021, the STRIPS market provides another illustration of the idiosyncratic pricing of US Treasury bonds, that is, of the occasional failures of the law of one price to describe prices accurately. Table 1.7 isolates one such case by reporting the prices of three STRIPS that all mature on May 15, 2030. In theory, because each of these zero coupon bonds pay $1 on May 15, 2030, they should all sell for the same price. But they don't. The C‐STRIPS maturing on that date are priced at 85.95, while two P‐STRIPS, one from stripping the 0.625s of 05/15/2030 and the other from stripping the 6.25s of 05/15/2030, are priced at 86.85 and 87.04, respectively. Reiterating the discussion earlier, these price discrepancies do not necessarily imply an arbitrage opportunity of buying the C‐STRIPS and shorting one of the P‐STRIPS because of likely significant market frictions. An investor planning to buy and hold one of these zero coupon bonds to maturity, however, would certainly be most attracted to the C‐STRIPS.

Figure 1.2 shows a broader pattern of the idiosyncratic pricing of STRIPS. The thick, round data points are C‐STRIPS prices, and the plus signs are P‐STRIPS prices, where prices are on the left axis. As an aside, because STRIPS prices are discount factors times 100, the C‐STRIPS data points depict a collection of discount factors out to 30 years, down to a value of 48.60 at 30 years. But returning to the main point, many P‐STRIPS prices are clearly not identical to C‐STRIPS prices of identical maturity. To highlight this point, the difference between P‐STRIPS and C‐STRIPS prices of the same maturity are graphed as short dashes against the right axis. A few of the differences are negative, but most are positive, and some significantly so, reaching a peak of 1.91 per 100 face amount at a term of 18.5 years.

TABLE 1.7 Prices of STRIPS Maturing on May 15, 2030, as of May 14, 2021.

| STRIPS | Price |

|---|---|

| C‐STRIPS | 85.9453 |

| P‐STRIPS of 0.625s of 5/15/2030 | 86.8549 |

| P‐STRIPS of 6.25s of 5/15/2030 | 87.0412 |

FIGURE 1.2 Prices of US Treasury C‐STRIPS and P‐STRIPS, as of May 14, 2021.

1.6 ACCRUED INTEREST

This section describes the market practice of separating the full or invoice price of a bond, which is the price paid by a buyer to the seller, into two parts: a flat or quoted price, which appears on trading screens and is used when negotiating transactions; and accrued interest. Full and flat prices are also known as dirty and clean prices, respectively.

For concreteness, consider an investor who purchases $10,000 face amount of the US Treasury 0.625s of 08/15/2030, for settlement on May 17, 2021. The bond last made a coupon payment of ![]() on February 15, 2021, and makes its next coupon payment of $31.25 on August 15, 2021. See the timeline in Figure 1.3.

on February 15, 2021, and makes its next coupon payment of $31.25 on August 15, 2021. See the timeline in Figure 1.3.

Assuming that the buyer holds the bond through August 15, 2021, the buyer collects the semiannual coupon on that date. But it can be argued that the buyer is not really entitled to the whole coupon because the buyer will have held the bond for only three months, that is, from May 17, 2021, to August 15, 2021. More precisely, using what is known as the actual/actual day‐count convention, and referring again to Figure 1.3, the buyer should receive only 90 of the 181 days of the coupon payment, that is, ![]() . The seller, on the other hand, who presumably held the bond from the previous coupon date to the settlement date, should collect the rest of the coupon, namely, the accrued interest from February 15, 2021, to May 17, 2021, which is

. The seller, on the other hand, who presumably held the bond from the previous coupon date to the settlement date, should collect the rest of the coupon, namely, the accrued interest from February 15, 2021, to May 17, 2021, which is ![]() .

.

FIGURE 1.3 Timeline for Computing the Accrued Interest on the 0.625s of 08/15/2030 for Settlement on May 17, 2021.

A conceivable institutional arrangement would be for the seller and the buyer to divide the coupon payment on the next payment date, but this would undesirably require additional arrangements to ensure compliance. Instead, market convention dictates that the buyer pay the seller the $15.711 of accrued interest on the settlement date, and that the buyer keep the entire coupon of $31.25 on the coupon payment date.

The flat or quoted price of the 0.625s of 08/15/2030 on May 14, 2021, for settlement on May 17, is 91.78125. The full or invoice price, which is defined as the flat or quoted price plus accrued interest, is ![]() . For the particular trade just described, of $10,000 face amount, the invoice amount is

. For the particular trade just described, of $10,000 face amount, the invoice amount is ![]() , or, equivalently,

, or, equivalently, ![]()

![]() .

.

At this point, it becomes clear why earlier in the chapter it is noted that prices are full prices. With bonds paying coupons on May 15 and November 15, and with trades settling on Monday, May 17, 2021, buyers have to pay sellers two days of accrued interest.

The full price of a bond, the amount a buyer actually pays to purchase a bond, should equal the present value of a bond's cash flows. Mathematically, denote the flat price of the bond by ![]() , accrued interest by

, accrued interest by ![]() , the present value of the cash flows by

, the present value of the cash flows by ![]() , and the full price by

, and the full price by ![]() . Then,

. Then,

Equation (1.5) reveals that the particular market convention used to calculate accrued interest does not really matter. For example, the accrued interest convention just described is conceptually too generous to the seller because, instead of being made to wait until the next coupon date, the seller receives a share of the coupon at settlement. But the accrued interest convention changes neither the present value of all cash flows, ![]() , in Equation (1.5), nor the full price,

, in Equation (1.5), nor the full price, ![]() , which is the amount actually exchanged at settlement. The convention only changes the quoted market price,

, which is the amount actually exchanged at settlement. The convention only changes the quoted market price, ![]() , relative to the calculated amount of accrued interest. If accrued interest is in any sense too high, the market reduces

, relative to the calculated amount of accrued interest. If accrued interest is in any sense too high, the market reduces ![]() accordingly.

accordingly.

Having made this argument, why bother with the accrued interest convention in the first place; that is, why not just quote bonds using the full price? The answer is told in Figure 1.4, which draws the full and flat prices of the 0.625s of 08/15/2030 from February 15, 2021, to September 15, 2021, under the simplifying assumption that interest rates are constant at the approximate market rate of 1.60% over the entire period.7

Figure 1.4 shows that the full price changes dramatically over time – including a sudden drop on August 15, 2021 – even though the market, in terms of interest rates, is unchanged. The flat price, by contrast, changes only gradually over time. Therefore, when trading bonds day to day, it is more intuitive to follow flat prices and negotiate transactions in those terms.

The behavior of the prices in Figure 1.4 can be understood readily. First, as of February 2021, the price of the bond is below 100, because its coupon rate is below the market rate for its maturity. But as the bond matures, its flat price approaches 100. (The dynamics of prices at below and above market rates are discussed further in Chapter 3.) Second, within a coupon period, the full price of a bond increases over time as its cash flows get closer to being paid, that is, as their present values increase. But from just before the coupon payment date to just after, the full price falls by the coupon payment: the coupon is included in the present value just before the payment, but not included just after. The flat price, by contrast, which equals the full price minus accrued interest, rises more gradually than the full price and does not fall precipitously just after the coupon payment. Because accrued interest just before the coupon payment nearly equals that coupon payment, subtracting accrued interest from the full price leaves the flat price essentially without that coupon – both just before and just after its payment date.

FIGURE 1.4 Full and Flat Prices for the 0.625s of 08/15/2030, Assuming Constant Interest Rates.

1.7 DAY‐COUNT CONVENTIONS

As mentioned in the previous section, accrued interest is calculated using the actual/actual convention, that is, by dividing the actual number of days from the last coupon payment by the actual number of days between coupon payments. Hence the term “actual/actual” for this day‐count convention.

The actual/actual convention is commonly used in government bond markets, but, in other markets, different conventions are used. Two of the most common are actual/360 and 30/360. The actual/360 convention divides the actual number of days between two dates by 360. The 30/360 convention calculates the difference between two dates under the assumption that there are 30 days in each month, and then divides that difference by 360. To illustrate, there are 75 actual days between June 1 and August 15: there are 29 days from June 1 to the end of June; 31 days in July; and 15 days to August 15. The 30/360 convention, however, assumes that there are 30 days in every month, including July, giving a total of ![]() or 74 days. Money markets typically use the actual/360 convention; swap markets use either actual/360 or 30/360; and corporate bond markets typically use the 30/360 convention.

or 74 days. Money markets typically use the actual/360 convention; swap markets use either actual/360 or 30/360; and corporate bond markets typically use the 30/360 convention.

NOTES

- 1 Scheduled bond payments that do not fall on a business day are made the following business day. For example, because May 15, 2022, is a Sunday, the coupon payment due that day would actually be paid on Monday, May 16, 2022.

- 2 For ease of exposition, this section assumes that the coupon and maturity dates of the bonds listed in Table 1.2 are exactly 0.5 years apart. A more precise construction of discount factors would use the exact number of days between cash flow dates.

- 3 Discount factors will not necessarily fall with term if interest rates are negative.

- 4 Market participants often use the term arbitrage more broadly to encompass trades that could conceivably lose money but promise large profits relative to risks.

- 5 Shorting a bond means selling a bond one does not own. The mechanics of short selling bonds is discussed in Chapter 10. For now, assume that a trader shorting a bond receives the price of the bond at the time of sale and is obliged to pay all of its coupons and its principal amount on their respective due dates.

- 6 Making P‐STRIPS fungible with C‐STRIPS would not affect either the total or the timing of cash payments by the Treasury but could change the amount outstanding of particular bonds.

- 7 More specifically, it is assumed that the continuously compounded interest rate for all terms is constant at 1.60%.