3. Choosing Your Destiny: How to Design a Winning Innovation Strategy

One of the first rules of innovation is that you must clearly decide how your organization is going to play the innovation game. This is senior management’s responsibility; there is no menu of generic strategies from which to choose. Each company’s management team has to craft its own innovation strategy, adapt to changing conditions, and choose the right time to make key moves.

The innovation strategy must support the business strategy. The amount and type of innovation (radical, semiradical, and incremental) varies depending on the strategy and the competitive environment. As with anything important, timing is everything.

It is crucial that the people in the organization understand the innovation strategy. Without a clear game plan, and without alignment of the key players in the organization, you cannot succeed in innovation.

Play to Win and Play Not to Lose Strategies

A study that scrutinized why some firms innovate significantly more than others found that, in general, dominant firms are more aggressive innovators than nondominant firms.2 However, dominance is not a strategy—it is an outcome. You need to define more than dominance to have a viable innovation strategy.

Within the Innovation Matrix, an organization may choose to either devote most of its resources to a particular part of the matrix or spread them out, creating a diverse portfolio of innovation investments across the matrix. Depending on the center of gravity and diversity of the investment within the matrix, we can talk about two classes of innovation strategies: Play to Win (PTW) and Play Not to Lose (PNTL).

Play to Win Strategy

For an organization to launch a PTW strategy, there must be an emphatic “Yes” in response to the question “Is the innovation investment we are making expected to create one of the key sources of our competitive advantage?” The goal of a PTW approach investment is to produce significant competitive advantages that its competitors will not be able to easily or quickly match.

PTW is a market-leading strategy that relies heavily on semiradical innovation to drive transformation in the organization and create market-changing ideas and products. In the PTW innovation mode, a company invests in changes in technology and business models with the intent of outpacing its competitors through radical innovation or, alternately, by wearing them down with repeated, frequent salvos of different types of innovation—incremental, semiradical, and radical. Either way, investing in a PTW innovation strategy commits a company to a portfolio of investments that are fundamental for (although not the only element of) the organization’s ongoing competitive success.

A PTW strategy is typical of high-technology startups. These companies are highly focused on bringing one new technology or business model to market. Frankly, one new thing is almost all they have, and their future is almost entirely dependent on it. The failure rate for small companies following this strategy is large, reflecting the high risk involved with this strategy, whether it comes from the technology delivering the value promised, from the market developing fast enough to value the technology, or from the management executing on the strategy. The other key contributing factor in the failure rate of these high-tech startup companies is that they usually have only one or two innovation investments and do not have a strong investment portfolio. The lack of depth in their portfolios is what makes the PTW strategy extremely risky.

Because of their limited resources, these young companies must be very focused in the beginning. Ironically, once the startups are successful, they need to shift to a more diversified innovation portfolio that puts a premium on additional incremental innovation (for example, incremental changes to protect and capture maximum value from their initial radical or semiradical innovation). But this is not easy to do, and many companies have problems shifting from a strategy that emphasizes big radical innovation to a strategy that includes a combination of radical, semiradical, and incremental innovation investments (such as a diversified portfolio). Along with changing the investment portfolio and modifying the strategy and the processes, it is common to see significant turnover at the top of the organization, from entrepreneurs to seasoned managers.3 Selecting and executing the innovation portfolio is management’s responsibility. Failing to adequately change the strategy requires intervention of the board or the investors.

The early part of the dotcom phenomenon offers numerous examples of PTW strategies from startups, with both success and failures as outcomes. On the failure side, Webvan received more than $700 million in funding; however, the company burned out in less than four years while attempting to create a new business model based on a new technology. Webvan’s proposition was to use the web as the supermarket storefront for customers selecting products, as in a regular supermarket; the company then would use its fleet of trucks to deliver the order to their door. The technology was the web-based software, still in a state of flux at the time, but probably not at the extreme of the newness axis. The business model relied on a significant change in people’s shopping habits and the assumption that avoiding costly retail space and centralizing warehousing was cheaper. The risks were high, in that both technology and (mostly) the business model were new. However, the potential rewards were also significant, as reflected in Webvan’s market capitalization at its peak: $8.81 billion. Webvan energetically attacked the market with a clear PTW strategy. Webvan ended up closing its operation in July 2001.

In contrast, Amazon.com is a successful example of a PTW strategy. The risks were similar, in that Amazon also relied on an evolving software technology and a new business model that required both a significant change in the purchasing habits of book customers and a significant redesign and streamlining of the book supply chain. Amazon redefined a best practice by selling single books in an industry that, as late as the early 1990s, was accustomed to selling pallets of books (shipping a single one was considered impossible); this process innovation in order management continues to serve the company well today. Amazon also energetically attacked the market with a PTW strategy. However, the company was able to turn the sale of books and other products over the web into a successful business model via its PTW strategy.

Managers in larger, more established firms do not need to “bet the company,” as startups often do. Their broader, available resources allow them to cover a larger portfolio of investments in the Innovation Matrix, providing a hedging function and significantly lowering the risks. Many large firms (namely, GE, Apple, and Google) have a clear PTW bent to their strategy. These companies have committed to an investment portfolio that is designed to provide a formidable flow of innovations that will contribute to their dominance of their business sectors. Toyota’s development of lean manufacturing and the introduction of the Prius hybrid auto are examples of a PTW innovation strategy.

For many companies, at any given moment, it is not prudent to adopt a PTW strategy. The external or internal conditions may make such a strategy choice too risky. Sometimes it is advantageous to stay in the game, adopt a Play Not to Lose (PNTL) strategy, and ultimately win through the ability to outpace competitors in pushing an innovation strategy with a significant incremental component to it or at the right opportunity.

Play Not to Lose Strategy

Sometimes less than optimum external or internal conditions do not allow a company to adopt a PTW approach. For example, if the external competitive environment is extremely intense or uncertain (for example, there are too many strong competitors or regulatory roadblocks, or there is a high degree of uncertainty due to a shifting regulatory environment or uncertain economics), it is advisable to adopt a PNTL strategy. Likewise, if an organization has significant internal constraints (such as inadequate resources or a culture that is caught up in a noninnovative mentality), a PTW strategy may not be a viable option. The potential costs and risks of pursuing a PTW strategy under those circumstances are likely to outweigh the benefits.

PNTL is a strategy that typically includes more incremental innovation in the portfolio than a PTW strategy and aims to ensure that the company can stay in the game by moving quickly and taking calculated risks, sometimes moving first or else matching or surpassing any moves by competitors. Johnson & Johnson apparently opted for a PNTL strategy in many of its businesses, including reliance on line extensions, cost cutting, and acquisitions. With few promising drug deliveries in the near term, Johnson & Johnson adopted a more conservative strategy to hold off the competition until more promising opportunities present themselves.4 Hyundai’s early moves also reflected a PNTL strategy aimed at keeping the company in the game as the automotive giants slug it out.

Following a PNTL approach, the company watches for improvements in the external environment, makes improvements in its internal capabilities, attempts to wear down the competition, and looks for opportunities to shift to a PTW strategy at the appropriate time.

Sometimes a PNTL can lead a company to the forefront of an industry without shifting to a PTW strategy. Companies with PNTL strategies are often in fragmented industries where changes to technologies and business models occur relatively infrequently. In this environment, the winners are companies that consistently beat competitors in making incremental improvements to technologies and business models. These leaders make PNTL strategies the norm for the entire industry. Such markets are for marathon runners (with the winner emerging as the one most able to constantly deliver) rather than for sprinters. These companies may still choose to invest in the outer quadrants, discussed in Chapter 1, “Driving Success: How You Innovate Determines What You Innovate,” of the Innovation Matrix (semiradical or radical innovation). However, these investments are not intended support a company in becoming a PTW player; they are meant to keep the company connected to the activity in these quadrants and to be able to move quickly if a radical innovation happens to shake the market.

Still, we have seen that companies that follow this sort of PNTL model run another significant risk. This strategy is highly vulnerable to competitors that break from the pack and shift to a PTW strategy that increasingly relies on semiradical or radical innovations. When these shifts happen, PNTL companies can be left with insufficient capability to match semiradical and radical innovations and little ability to compete in this new environment. Being lulled into believing your PNTL strategy is working is also a danger. Mattel learned this lesson when a competing line of dolls introduced in 2001, called Bratz (produced by MGA Entertainment), significantly cut into Mattel’s Barbie sales.5

If you look around an industry at any given moment, you will find many companies that exhibit important aspects of the PNTL behavior, such as being risk averse and not wanting to attempt to first commercialize risky semiradical or radical innovations that appear to potentially yield significant competitive advantage. However, this PNTL behavior may not be the result of conscious management choices. Sometimes PNTL strategies exist because the management cannot commit to a clear PTW strategy. In that case, PNTL is a compromise among parts of the organization that do not have the same view of what should be done to succeed. That sort of compromise is a very dangerous strategic choice because it blunts the effectiveness of execution. People cannot execute at maximum efficiency, speed, or effectiveness if they are getting confused signals. It is management’s responsibility to clearly specify and communicate the innovation strategy throughout the company.

PNTL is sometimes mistakenly called the “fast-follower” strategy. This is the wrong mental model. A PNTL strategy is not limited to following another’s move. To be successful, PNTL requires a mix of preemptive and reactive moves, all aimed at not relinquishing advantage and, whenever possible, causing competitors to expend more than their fair share of resources in their actions. So playing not to lose is not the same as following. An organization focused on just following eventually becomes limited in its competitive mindset and innovation capability, unknowingly relinquishing innovation opportunities that do not fit into the concept of following. Having said this, skilled fast-followers are often more successful than the early innovators. These fast seconds follow a PNTL strategy but deploy the capabilities to quickly copy and improve successful PTW companies to become leaders.6 They are ready to quickly jump after a successful innovation and deploy their business processes’ strengths—such as marketing, distribution, product development, or process technology—to beat the original innovator.

The recent competitive and regulatory environment in the U.S. electric utility industry has favored adoption of PNTL innovation strategies. While many companies attempted to be innovative in the 1990s, the swiftly changing regulatory environment and the failure of many initiatives forced many major utilities into a PNTL strategy. For the past five or more years, the major industry players have all bunched up around variations of a PNTL strategy.

However, there seems to be a turning point in the utility industry, and some utilities appear to be considering that a switch to a PTW strategy is warranted. For example, early in 2004, John Wilder, former CFO at Entergy Corporation, became president and chief executive of TXU Corporation. In his remarks to investors, Wilder made it known that TXU’s back-to-basics and PNTL days were over, and that his intent was to strive for a position of industry leadership for TXU. CEOs of companies such as Constellation Energy Group, Dominion Resources, Sempra Energy, and Centrica have begun to set new business objectives and migrate to PTW strategies.

One of the major questions facing the other companies in the industry is how quickly they can shift strategies to a new PTW to address this shift by the other utilities. If those remaining companies are too slow in changing to a PNTL strategy or they lack the capabilities to shift without undue risk, they face the prospect of being trapped in a PNTL strategy at the wrong time. Choosing a PNTL innovation strategy can be a smart management decision. However, being forced into a PNTL strategy because a company is not prepared is poor management.

In another part of the energy sector, the leading oil companies decreased their investment in finding new oil in 2003 and 2004. Lee Raymond, former CEO of ExxonMobil, the world’s largest energy group, said he believed that most of the world’s largest oil fields had already been found and that the next opportunities would come when investment in countries such as Russia, Iraq, and Libya become politically possible. This harsh reality of diminished exploration sent shock waves through the leaders in the oil services industry, Halliburton and Schlumberger. They had to decide the right innovation strategy in the face of significant industry upheaval: Is it the right time to play to win?

While the two big players made decisions and second-guessed each other, the smaller players in the industry, such as Weatherford and BJ Services, had to make similar decisions: Is it the right time for the small players to play to win, and attempt to grow and take a leading position in the industry? These innovation strategy decisions made in 2005 will determine the shape of the oil services industry in the years ahead.

Utilities and oil service companies are not alone in this regard. Many other industries face similar challenges in deciding when to shift from PNTL strategies. For example, healthcare providers have been struggling for survival, and the entire industry has been locked in a PNTL innovation strategy. The major emphasis has been on cost reduction and incremental improvements to shore up revenues and profits. However, some players, such as Sutter Health, have shown significantly improved financial performance. With that change, some of the profitable companies may decide to shift to a PTW strategy because the timing looks good to create important competitive advantage. That shift to PTW by a few key players could change the competitive dynamics of the industry significantly.

A very interesting example of a company using a PNTL innovation strategy against a PTW strategy occurred in the so-called U.S. baby diaper wars of the 1980s and 1990s. Kimberly-Clark (KC), facing Procter & Gamble (P&G) and a host of smaller independent manufacturers, did not appear to have the positioning necessary to dominate the market, although it would have liked to. Darwin Smith, CEO of KC at that time, was an intense competitor who focused his company on creating value. However, P&G, one of the earliest participants into the diaper business arena, was fiercely defending its leading market share and profitability. P&G had dedicated significant resources and clearly signaled that it was not likely to be run out of the market. P&G was investing large amounts of resources on innovation.

Although it could not dominate the market with the resources at hand (it would have been very hard to outspend P&G), KC did not withdraw. KC challenged every one of P&G’s innovation moves. In addition, sometimes the company took the initiative and introduced customer-preferred product features (such as training pants) first. Other times, it quickly and effectively countered P&G’s innovations, responding with comparable or improved features and performance that mimicked the P&G innovation (such as boy and girl diapers). KC’s PNTL innovation strategy combined preemptive and reactive innovations that kept P&G off balance and unable to dominate the market. The diaper war intensity seems to have abated, but it has not disappeared. Both KC and P&G are still slugging it out.

It is often the case that the external and internal forces do not dictate that a company adopt a pure PTW or PNTL strategy. They point to something in between the two extremes.

Too Much of a Good Thing

Can you have too much innovation? We should not be misled by the frequently used expression “Innovate or die.” Those who espouse this slogan firmly believe that massive doses of radical innovation are required to survive. Is radical innovation truly necessary for survival for all organizations at all times?

A lack of innovation, especially radical innovation, can lead to failure. However, investing in radical innovation at the wrong time or in the wrong amounts can be just as fatal. In other words, it is possible to “innovate and die” by taking the wrong kinds of risk and by playing the wrong kind of strategy.

There is another risk with taking the expression “Innovate or die” too much to heart. Too many innovative ideas out there for companies to process clouds their judgment on which ideas are truly great.10 Clouded by the excess, the companies take on too much innovation and the wrong types of innovation, and waste their investments.

Clearly Defined Innovation Strategy Drives Change

The following case study of Procter & Gamble shows that success in innovation requires a clearly defined innovation strategy that matches the current realities in the company. P&G had great difficulty transforming from its conservative and cautious organization into one that could embrace more aggressive doses of innovation. It also learned that attempting to change everything at once is not a formula for success.

Do You Select an Innovation Strategy?

“Over time every business model and strategy goes stale in our fast-forward economy. Strategies reach their sell-by date faster than ever.”13

A company’s innovation strategy needs adjustment over time. A number of internal and external factors affect the selection of the best innovation strategy (see Figure 3.1). These affect the choice of innovation strategy and the shape of the portfolio: Play to Win or Play Not to Lose.

Figure 3.1. Factors to consider in choosing an innovation strategy

• Technical capabilities: The amount of technology innovation depends to a large extent upon the current capabilities that the company has internally or can access through its innovation network. A company that has traditionally competed on its marketing skills and incremental technology improvements will have a tough time suddenly including a semiradical technology dimension to its strategy.

• Organizational capabilities: The ability to nurture innovation also depends on whether the company has the organizational capabilities to do it. Shifting to a more radical innovation approach will not happen if the organizational and management capabilities are not present.14

• Success of the current business model: The difficulty that successful companies have in changing has been repeatedly documented. It has been described as core capabilities becoming core rigidities or the inability to grow internal ventures in successful companies. The greater the success, the greater the potential resistance to change.15

• Funding: Having the necessary economic resources is an obvious, albeit sometimes forgotten, requirement. However, too much funding may be as dangerous as too little. For example, the startups of the late 1990s and early 2000 were funded with a lot more money than they actually needed. The result was waste—a misallocation of resources chasing business models that were inadequately tested. A less generous funding environment forces innovation teams to carefully plan and test the assumptions of the model before scaling up.

• Top management vision: The last internal factor is top management’s vision. Management has a large set of options to position the company, and management talent has a very relevant role in selecting and evolving the company’s innovation strategy.

External Factors

Internal factors are not the only formative forces; external forces can also shape the innovation strategy:

• Capabilities in the external network: Accessing relevant capabilities is crucial. Development of new technologies or business models usually requires collaboration with other organizations that have complementary resources; for this, you need a network that reaches inside and outside your organization (Chapter 4 deals with the critical aspect of innovation networks in more detail). The ability to create sustainable alliances with these partners becomes important in deciding the innovation strategy going forward.

• Industry structure: The industry itself is a factor. A careful analysis of this structure points out where the main obstacles and opportunities for innovation reside. Understanding the dominant industry value chain, who dominates and why, and the structure of the barriers to entry are important inputs to the design of an innovation strategy.

• Competition: The quality and speed of innovation of your competitors as well as your innovations will determine the shape of the market in the years to come. While your organization may be well positioned in the current market, competitors could change or new competitors could enter, especially if the competitive dynamics change drastically.

Useful questions include these: Do strategies of your competitors open any doors for you to adopt a PTW approach? Do their actions force you to consider a PTW approach? Does their approach make a PNTL strategy relatively attractive? Without a clear innovation leader present in the arena, is an outsider likely to jump into the game and change the rules?

• Rate of technological change: As the world becomes more technologically advanced, the life of a product will become shorter. When new advances outdate your product, it is important to identify the change approaching before your product goes stale.16 For example, Panasonic realized that its traditional analog products were susceptible to replacement by a whole new class of digital technologies in which the company was not well versed. Panasonic set up an incubator in Silicon Valley in 2000 to quickly move up the learning curve and gain access to emerging digital technologies.

Successful long-term products can sometimes blind companies to new trends that their competitors will ultimately pick up—the competitor’s dilemma.

Updating and improving your company’s innovation strategy must address these elements. However, no formula will yield the best strategy; each company is unique even though they may all share the same competitive environment. What is considered a threatening situation for one company, resulting in a PNTL strategy, could be considered an opportunity for another.

Risk Management and Innovation Strategy

When deciding what innovation strategy to pursue, risk management comes quickly to mind. Assuming that no significant disruptions occur to the competitive arena, as we move up and right on the Innovation Matrix, the level of risk we take is higher. If a disruption has occurred, incremental activities that do not address the disruption could be the most risky path. However, assuming that a disruption has not occurred recently, adding a greater component of radical innovation increases the risk. Therefore, a Play to Win strategy is often riskier than a Play Not to Lose strategy because it relies on a larger component of semiradical and radical innovation.

For companies intent on leading and changing the industry, the center of gravity of investment will move more toward the semiradical and radical innovation quadrants. These companies rely on being first and creating value through larger leaps of technology or business model innovation. However, to keep from increasing their risk unnecessarily, these companies invest enough in incremental innovation to be fast-followers and quickly assimilate the little steps that their more conservative players take. Apple’s revolutionary combination of iPod and iTunes innovations was quickly followed by incremental improvements aimed at competitors’ responses to the introductions. Apple rapidly followed the iPod and iTunes by introducing the iPod mini and sharing the iPod technology with Hewlett-Packard, effectively blunting lower-end copycat versions of the iPod and online music offerings from Sony and Microsoft.

The center of gravity and the breadth of the innovation portfolio determine the level and type of risk that needs to be managed during execution. Risk-management processes, mostly portfolio design techniques, should minimize the risk exposure of a company (see Chapter 5, “Management Systems: Designing the Process of Innovation”).

Innovation Strategy: The Case of the Pharmaceutical Industry

It is useful to consider a leading industry segment and the innovation challenges it faces. Consider the pharmaceutical industry, a field with powerful, innovative players.

Every week, several articles appear describing the difficulty leading pharmaceutical companies have in maintaining their new product pipeline. Historically, the companies have successfully innovated to fuel their significant growth. For example, in 2002, some 44 million people around the world lowered their cholesterol by taking daily doses of Lipitor. In its six years on the market, Lipitor has become the largest-selling pharmaceutical in history. Within the next few years, it could very well become the world’s first drug to reap $10 billion a year.17

However, for many companies, it is getting harder to innovate successfully, and the flow of viable new products has been difficult to maintain. In the future, Pfizer will need a strong portfolio of novel drugs to produce double-digit growth on its mammoth revenue base. For that, the company is counting on a game plan that includes examining drug targets whose role in diseases is already well established and then choosing new targets that closely resemble these. The company is taking aim at a family of 21 enzymes that the company already understands well.18

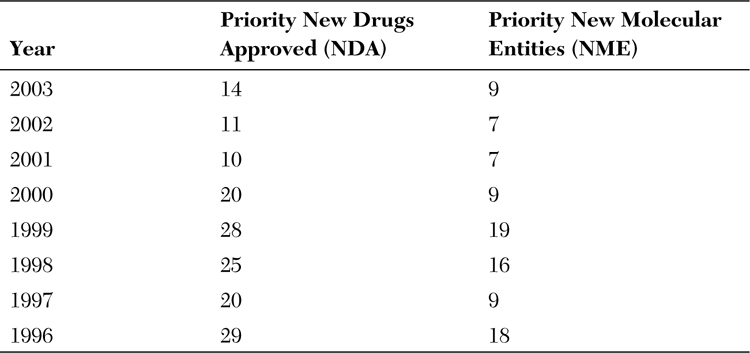

In 2002, the leading pharmaceutical companies spent approximately $35 billion on R&D.19 According to a study by Tufts University, it now costs $800 million to develop each new molecule, including the cost of capital. The pharmaceutical companies are spending huge amounts on R&D and new product commercialization. Despite the enormous investment, the results have been poor, as you can see from Table 3.1.

Table 3.1. Number of New Drugs Approved by the U.S. FDA20

The list of companies that have been delayed or outright rejected by the U.S. FDA includes most of the industry elite: Pfizer, Glaxo SmithKline, Merck, and AstraZeneca. The problem does not appear to be related to lack of effort in R&D or poor innovation processes. Pharmaceutical companies have developed fairly sophisticated R&D processes in response to the huge risks associated with new product development in the industry. Generally, the companies consider themselves leaders in both spending and the management processes related to innovation. The root cause of the problem appears to reside in the innovation strategy.

Attempts to Solve the Innovation Problem

Leading pharmaceutical companies have tried to remedy their lack of success in innovation by improving their R&D through two methods. The first method is the use of scale. Companies have acquired other companies, thereby combining their R&D pipelines to hopefully attain economies of scale. Combining pipelines is a short-term fix that yields a temporary improvement. However, it does not solve the cause of the problem, and very quickly the company finds itself facing the same issue it sought to remedy: how to keep the product-development pipeline full of winners. The hope is that economies of scale will solve that problem long term. While economies of scale have proven valuable in some areas, such as selected types of manufacturing, the jury is still out on whether that approach will solve the dry product pipeline phenomenon.

The second approach major pharmaceutical companies use to solve their problems has been to develop closer ties to biotech and genome organizations in order to get better information on new molecules with promise for use in new drugs. This approach was intended to provide greater probability of success in identifying new molecules prior to the ultra-expensive and lengthy clinical trials. The trials cost millions of dollars and can take three to seven years to complete. In addition to being a drain on money and time, the success rate of clinical trials is fairly low. All too often, a company finds that it has invested huge amounts of its innovation money, resources, and time only to find out that the drug cannot be commercialized due to problems in the clinical test phase. On average, only one in ten is approved.

Biotech appeared to offer a more analytical and insightful method to screen potential molecules before the clinical trials. However, there has not been universal success with this approach to date. It may be that the additional insights gained via genome and biotechnology research have actually decreased the probability of successfully developing a new drug. Previously, the researcher knew of significantly fewer options for molecular intervention. Biotechnical and genome work to date has improved the clarity surrounding molecular interactions, but it has also multiplied the number of options for developing new molecules. With time, we may overcome this and begin to capitalize on the full value of biotechnical and genome research and development. However, at the moment, the effect is to “increase costs and timelines, not reduce them,” according to David Beadle, analyst at UBS Warburg.21

Changing the Innovation Approach

From an outsider’s perspective, it appears that some of the pharmaceutical companies could benefit by changing their mental model of innovation and pursuing alternate innovation approaches. In short, they need to solve their innovation problem by being innovative, looking in areas that they have historically avoided.

Pharmaceutical companies usually invest in developing technologies that will produce major new blockbuster drugs (drugs with massive market potential). The risks of developing these new blockbusters are huge, as was described previously, and the costs and resource commitments are massive. However, the potential gains for a successful breakthrough can be tremendous—in the billions of dollars, or more, of new revenue while the patent protection is in effect. The lure of this huge payoff keeps the pharmaceutical companies investing using the same strategy. In the future, this approach may have diminishing returns or, worse, become a major liability. It looks like the pharmaceutical companies have an unbalanced innovation portfolio and are addicted to technology.

For example, generics have threatened GlaxoSmithKline’s biggest sellers, including the antidepressant Paxil. To deal with this, GSK has introduced several modified versions of older drugs, including Wellbutrin XL and Paxil CR for depression and Augmentin XR, an antibiotic. It appears that the company feels the success will lie in the potential big sellers it has ready for introduction in the next two years.22

It would be prudent for the pharmaceutical companies to consider shifting their strategy and some of their innovation efforts away from pursuing semiradical technology changes, to instead pursue breakthroughs in new business models. This would be the equivalent of becoming “the Southwest Airlines” or “the Dell” of the pharmaceutical industry and would mean creating a new business model to challenge the traditional players in ways they cannot easily counter. Imagine, for example, using an open source approach for drug development, similar to the growing, powerful trend in the software industry.

Consider what would happen if a major pharmaceutical company invested and operated in the second- or third-tier markets for selected types of pharmaceuticals. While considerably smaller than the blockbuster markets, these markets could be very profitable and attractive. Some companies have already successfully competed for smaller markets. For example, before Johnson & Johnson acquired ALZA in 2001, it created attractive profits in markets that had sales of $100 million per year or less. ALZA’s innovation process was able to effectively develop and commercialize a range of successful products in those markets. However, after the acquisition, ALZA’s business model changed. Since then, the company has pursued innovations in the blockbuster arena, avoiding the business model that led it to its historic success. Likewise, Genentech launched the first highly targeted therapy five years ago and is taking the concept to the next level by demonstrating that a big-league drug maker can achieve heady growth without a heavy focus on blockbusters.23

Alternatively, consider a pharmaceutical company that consciously creates a more balanced portfolio, including the development of new business models. The company would invest in changes to its business model to create competitive advantage to complement its technology investments. The business model innovations would allow it to serve markets better than its traditional competitors, who, bound by their historical business models, could not compete. The company would also maximize the return on its innovation investment.

Innovation options that could be considered include these:

• Increased levels of service

• Change in the supply chain or a similar operational breakthrough

• Closer, better connections to the payers

These are some of the ways that a company can explore alternate innovation approaches and refresh its strategy. Of course, there are others as well, including returning to the six key levers for innovation and assessing which of these could be best used to achieve powerful and properly tailored innovations.

Strategy and the Innovation Rules

Defining the innovation strategy and the resulting portfolio characteristics (Play to Win or Play Not to Lose and the associated mix of incremental, semiradical, and radical innovations) is the first major responsibility of a company’s leadership. Forming the strategy in the context of the Innovation Model and defining the balance of the portfolio is the responsibility of the leaders. It defines the direction and magnitude of the company’s innovation efforts, it sends clear signals to the company regarding the importance of innovation, and it facilitates execution.

Steve Jobs has been the leading force in defining Apple’s innovation strategy and innovation portfolio. He said, “The way we look at it is we don’t want to get into something unless we can invent or control a core technology. The core technology (of consumer devices) is going to be software. We’re pretty clever at hardware ... but the competitive barrier will be software. The more consumer products evolve, the more they will look like software in boxes.”24 You can argue with his logic or his conclusions regarding the competitive role of software in consumer goods, but his vision is clear and his message to his team at Apple is unambiguous: Fill the portfolio with defensible software innovations. Blend in other innovations, but put your focus on innovative software.

Jobs stepped up to the strategy and portfolio leadership requirements by answering three of the most important questions:

• How much innovation does my company need?

• In what areas should I focus the innovation?

• What portfolio of innovation types do I need? How much business model innovation? How much technology innovation? What mix of incremental, semiradical, and radical innovations?

Senior management needs to identify its core competencies and innovate around them. Apple, Wal-Mart, P&G, Dell, GE, and Toyota have all focused their innovation of business models and technology on their core competencies. Not all companies need large amounts of innovations, but they need them aligned with their competencies and strategy. Without a clearly defined and communicated innovation model and strategy and a clear characterization of the type of innovation portfolio required, employees cannot execute well.