5. Management Systems: Designing the Process of Innovation

Systems and Processes Make Things Happen

Having examined strategy in innovation and the various options for structuring your organization to best enable innovation to thrive, we next consider systems.1 The decisions you make regarding strategy guide where you focus your innovation efforts. The structure you put into place acts as the foundation for the innovation process. However, even with the proper strategy and structure in place, innovation could fail if your systems are inadequate. The management systems are the mechanisms that, to a great extent, make innovation happen.2

In small organizations, innovation usually happens as a natural occurrence through the insight, talent, and interaction of a small group of people. For example, a single inventor or a group of collaborators may launch a company with one robust idea. But as organizations expand, innovation does not happen anymore as a natural occurrence—the right people may not interact, the information may not flow to the right places, and the motivation to take risks may diminish. Organizations as large as General Electric or Procter & Gamble may develop silos—compartmentalized departments that barely communicate with each other, much less strive to innovate. This is why larger organizations need systems to manage innovation. Ignoring this and staying anchored in the idea that innovation naturally occurs leads to frustration and failure. The argument that large companies are not able to innovate may reflect the lack of acceptance of this basic idea: Innovation has to be managed; it does not just “happen.” IBM’s former CEO Sam Palmisano recognized this need for systemic management when he said that you have to create the right environment in the company for innovation to flourish.3

Innovation systems are established policies, procedures, and information mechanisms that facilitate the innovation process within and across organizations. They are the mechanisms by which innovation (and the other tasks of organizations) gets done.4 They determine the shape of daily interactions and decisions of staff: the order in which work happens, how it is prioritized and evaluated on the daily level, and how different parts of the organization use the organizational structure to communicate. Making decisions on a product enhancement requires communication between many parts of the organization, including R&D, manufacturing, marketing and sales, and finance, as well as processes and criteria for making the decisions. Two organizations with the same structure will get very different innovation results, based in part on the systems they have in place and the consistency with which they are followed.5 For innovation to happen successfully, an explicit process must be in place to manage all the steps of innovation, from design, to measurement, to reward.6

The Objectives of Well-Designed Innovation Systems

Many managers wrongly assume that structure and process are the natural foes of creativity. They feel that imposing any structure on creative people will have a detrimental effect on the results. What they don’t realize is that structure can enhance creativity if you build it and use it the right way.7

Innovation systems fulfill five important roles, as shown in Figure 5.1.8

Figure 5.1. The five roles of an innovation system

The first role of an innovation system is to increase the efficiency of the innovation process. The system needs to move great ideas from concept to commercialization with speed and minimum use of resources.

This role is especially relevant for incremental innovation, when following a defined set of stages and decision points accelerates time-to-market and increases the return on resources invested. For example, Tetra Pak uses the product stage gate management process to speed effective commercialization of product improvements by moving the innovation speedily through the steps of conceptualization, initial design, prototype design, and commercialization rollout. This function is comparable to that of systems in manufacturing that codify the stages of the process (according to cost, speed, or quality) to increase efficiency. However, innovation systems are not as detailed and structured as in the systems in an assembly line, where standard operating procedures dictate the actions of each person. Innovation systems—even those where efficiency is paramount—define relatively broad stages, leaving room for the team to maneuver.

The second role of innovation systems is to create the appropriate lines of communication within the company and with outside constituencies. As the innovation team demands specialized knowledge from other parts of the organization, systems facilitate timely access to it.9 The technology development team working on a new product needs to know what the customers want and the required product features. This directs and guides their efforts. The manufacturing team needs to inform the technology development team what is practical and cost effective as far as manufacturing for the new product. In addition, the manufacturing team needs to know what parts of the system to change. Throughout the internal organization and with external partners involved with the innovation, information regarding the development of the innovation and its consequences needs to flow and be used.

Cross-functional teams (widely used in product development) comprised of members with different functional expertise, such as R&D, manufacturing, sales, distribution, finance, and management, enable communication through the different knowledge bases of team members, or through a plan that describes when certain functions will join the team. Formalized systems also facilitate communication with internal and external partners through periodic planning and review meetings and explicit milestones. Microsoft and Compaq used these systems during software and hardware product development.

The third role of innovation systems is coordination between projects and team with minimum effort. An example of a coordination system is a plan to allow parallel work on projects with minimal communication. For instance, offices in California, London, and India that all use the same shared tracking system but at different hours can achieve three times the work in a day as other companies. Projects that run around the clock in different parts of the world are possible because of communication technology and the discipline that systems impose. Ensuring that resources are available on time is another coordination issue that systems facilitate. Tetra Pak was able to lower product development times by 40% by increasing the efficiency of its management systems, increasing the level of collaboration, and involving the right people at the right time.10

The fourth role is learning. We dedicate an entire chapter (Chapter 8, “Learning Innovation: How Do Organizations Become Better at Innovating?”) to the issue of learning because of its importance in innovation. Systems establish a discipline to manage the knowledge that is constantly created in innovation. Systems can capture the information on the innovation performance throughout the life of the initiative (idea through commercialization) and make it available to the innovation team and management. The information can be used to identify problems and potential improvements. More importantly, learning increases the understanding of the innovation process itself. Every time an innovation project is executed, something is learned about how to improve it, especially for incremental projects in which similar efforts are undertaken repeatedly. Innovation systems are like software; new versions are periodically released to improve on previous versions. A system for capturing and coding learning enables that to happen. Knowledge is also generated about the business model, the technology, and opportunities that are identified but cannot be pursued within the framework of the current project. Knowledge may be relevant not only to the current project, but also to future projects. In the case of DaimlerChrysler (now Chrysler Group LLC, part of Fiat S.p.A.), the company’s experience with electronic collaboration systems with its headset supplier provided important learning that it can apply to future projects regarding managing innovation within tight time constraints and working with partners spread across the globe.11 Similarly, Audi’s product development team learned that bringing the subsystem suppliers to the early stages of innovation planning was very valuable. After Continental Tire showed that it could create a smart tire capable of delivering breaking performance far ahead of what the industry had been able to do so far, Audi and other car manufacturers paid attention and built innovation systems that included the tire manufacturers.

Knowledge needs to be retained to benefit the organization and enhance competitive advantage. It is often said, “If our company only knew what our company knows, many problems would not exist.” Knowledge-management systems facilitate remembering or knowing what you know.

The fifth role of innovation systems is to align the objectives of the various constituencies. People throughout an organization need to understand the company strategy and its implications for operations. As a company grows larger, senior management cannot rely on informal, social interactions as the vehicle to achieve this alignment of understanding and behavior. A system is needed to ensure consistency of message and inclusiveness. Innovation systems also align organizational objectives with personal objectives. The information regarding the innovation performance needs to be communicated and compared to the innovation objectives. This allows people in the organization to assess how their actions fit the organization’s innovation objectives. If the performance does not match the objectives, time is spent analyzing the systemic cause of the discrepancy. This provides people a better understanding of the linkages between the innovation strategy and its operational context. Systems also reinforce optimal individual and group behavior to foster optimum innovation performance through well-designed incentive and reward systems.

Properly designed systems can help bring together the right people and the right knowledge to create the activities required to make innovation happen.

Choosing and Designing Innovation Systems

Innovation can be envisioned as a flow that starts with many and ends up with a few—a multitude of great ideas are created and winnowed, selected, and refined until only the few best are brought forward to commercialization. Systems manage the flow from the many ideas to the few that reach commercialization. This process is often envisioned as a funnel: broad at the opening, to accommodate the many ideas, and tapering to a small diameter, to allow the few to exit to commercialization. Figure 5.2 illustrates a typical funnel framework for innovation. In this depiction, innovation starts at the broad left side.

Figure 5.2. The innovation process

At the beginning of the process, a lot of ideas float around. This is the creative phase, and more ideas are developed than can or should be used. As ideas progress through the funnel, the process rejects some ideas (they leave the funnel) and continues to evaluate others (they move forward). Ideas move through the selection process until those that are selected receive a major resource commitment and move to the execution stage.12 Those ideas that become intellectual property move to the value creation stage.13 At the far end, the funnel grows larger again, reflecting that value creation should be maximized for the intellectual capital that has been developed (in other words, via application to more than one product or cross-licensing).14 Consider for a moment how many ideas must have been flowing into one end of the funnel at IBM, which obtained 3,288 patents in 2001—almost twice as many as the next nearest corporation to receive patents in that year.15

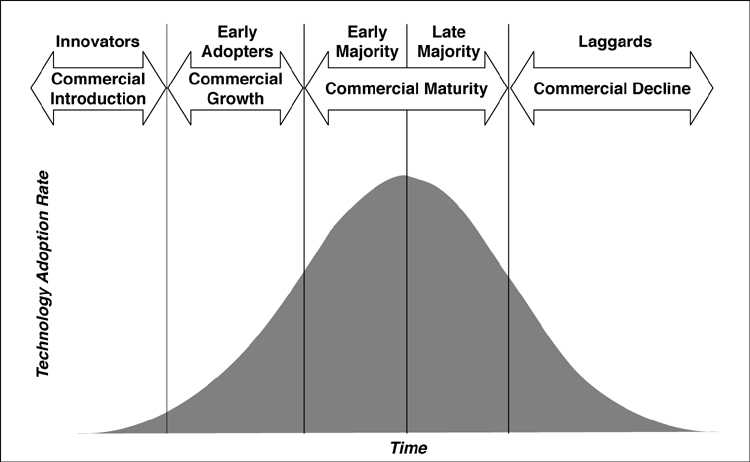

The first stage where management systems play a role is in ideation: generating ideas and moving them across the organization to where funding decisions are made. The second stage is the funding decisions themselves; selected innovations receive initial funding to move ahead or are discarded. The last stage is the execution of the innovation project (commercialization). The creation of value and commercialization of innovations follows a general path from early adoption to maturity (see Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Innovation commercialization process16

Whichever innovation systems you choose for your organization, they must be effective in moving through all three stages, from ideation, to selection, to execution, and then on to commercialization.17 Also, although it may appear that the stages progress in a linear fashion, they do not. Most often, the stages overlap and go through several iterations. It is important to note that creativity does not stop at the ideation stage, but permeates the whole process. For instance, a product improvement may be further enhanced or new innovations added to the product at any point in the innovation process, right up to and including the commercialization step.

Systems for Ideation: Seeing the Gaps

The engine of innovation is ideas. Ideas begin with the recognition and understanding that somewhere a gap exists. That gap may be large or small—a new product feature, a new business model element, an improved process technology, or an entirely new business model. Apple saw gaps in the way people acquired and used music, and created the iPod and iTunes. Gillette saw gaps in shaving products and created the new MACH3 razors and blades. Southwest Airlines saw gaps in the price of service for airline travel and designed an approach that delivered no-frills service at a significantly reduced fare. Whatever the size and type of gap, innovation depends on the realization that something is missing somewhere in the network that produces value for customers.

Because all ideas start with recognition of gaps, all processes for identifying great ideas are aimed at creating perspectives that make the gaps and holes visible. Sometimes top management sees the gap. Alternatively, a person in the ranks of a team may identify the gap. Whatever the source, these are autonomous ideas born from ingenuity or a “fortunate accident.”18, 19, 20, 21

The management challenge is to create an environment to nurture the generation of large quantities of great ideas about gaps (without getting in the way of day-to-day business) and to move the ideas to the next stages in the innovation process. When we talk about ideas, we specifically mean ideas that address a gap and have the potential to generate economic value. By the way, experience demonstrates that it is easy to generate a lot of ideas—just reward people on the number of ideas they submit, and the suggestion box will overflow. The challenge is to nurture the generation of economically viable ideas and to move a manageable number of ideas through the innovation process.

Structured Idea Management

Structured Idea Management (SIM) is a general ideation process that many companies and industries have successfully used for more than 20 years. For example, in the early 1980s, Canon used SIM to develop the concepts for new consumer cameras for the 1990–2000 timeframe. IDEO (a product design firm) uses this approach by mixing designers, social scientists, and others with valuable perspectives in a room where they intensely scrutinize a given problem and identify and explore possible solutions. It has been called managed chaos: a dozen or so very smart people examining data, throwing out ideas, and writing potential solutions on big Post-its that are ripped off and stuck to a wall.22 However, despite the appearance of chaos, at its core it is a highly structured process.

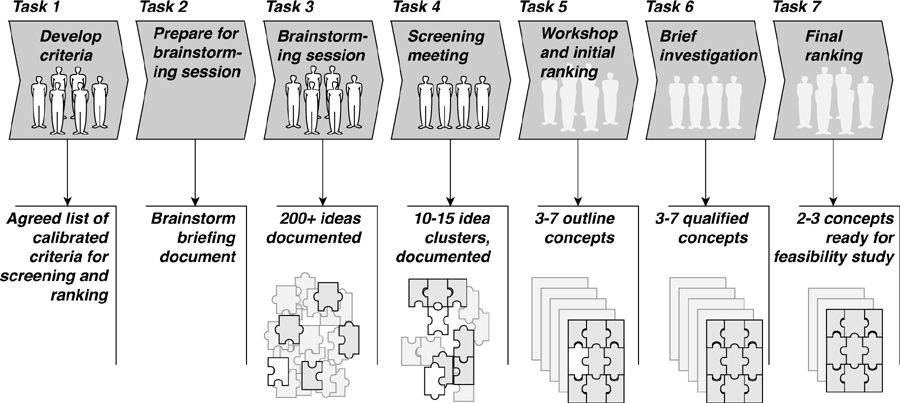

SIM is prototypical for many idea-management processes. Its individual steps (illustrated in Figure 5.4) are specifically designed to maximize the achievement of three desirable end goals:

1. Control of the working context/environment to ensure the maximum possible creativity

2. Use of the best and most rigorous screening mechanisms to ensure the highest-quality output

3. Explicit recognition and protocols for the creative “bundling” or “clustering” of “idea fragments” to create truly breakthrough concepts

Figure 5.4. The Structured Idea Management process23

SIM is designed to prevent the two most common mistakes companies make when undertaking the innovation process:

• Understanding the difference between assessing incremental versus radical ideas: Decisions about incremental and radical ideas tend to be made in the same forum, using the same criteria, although the two types of ideas need quite different approaches to development and selection. At such meetings, ideas that involve the greatest number of unanswered questions (which tend to be breakthrough ideas) are usually dropped first, leaving only the lowest-quality ideas.

• Recognizing the value of idea fragments: One of the most common mistakes that companies make is to use “brainstorming” meetings to generate finished concepts rather than thinking about fragments of ideas that, if put together, could yield a major breakthrough. They lose the best “fragments,” and the end results are again evolutionary developments from what has gone before.

Experimentation

To a larger extent, radical innovation relies on ongoing experiments that test, refute, modify, and validate potential radical breakthrough concepts. The participants in the X PRIZE contest used numerous experiments to test and refine the design of their space transportation technologies for commercial space flight. Scaled Composites has had to continually test, validate, refute, and refine the design and materials of construction of its innovative craft, Space-ShipOne. Every day has included experimentation to determine whether a better, faster, or cheaper way exists to hit the performance objectives—different materials, alternate fabrication techniques, or new controls technologies. Likewise, experiments with business models are a key activity for innovative initiatives. One of GE CEO Jack Welch’s recognized strengths was that he was always experimenting and looking for the opportunity to innovate. According to those close to him, he was always asking, “What is the business model? How can we change it to make it better?”24

Experiments provide a probing dynamic into new technical, business, and market spaces. Well-designed experiments provide insight and uncover hidden value. They provide learning that guides the radical innovation process by defining the right questions and suggesting the best answers.

One major study of players in the computer industry found that “using an experiential strategy of multiple design iterations, extensive testing, frequent project milestones, a powerful leader, and a multifunctional team accelerates product development.”25 A constant to remember throughout experimentation is the necessity to learn to expect the unexpected. 3M’s Scotchgard was a serendipitous discovery that was the result of a trivial accident. When trying to develop a rubbery material to resist deterioration from aircraft fuels in 1953, a few drops fell on a researcher’s new tennis shoe. Nothing could wipe off the substance, and the researchers had the presence of mind to realize that they had discovered something that repelled both water and oil. “The prepared mind notices when something doesn’t go as expected, and curiosity is piqued by observation,” says Patsy Sherman, the discoverer and developer of Scotchgard.26

Prototyping

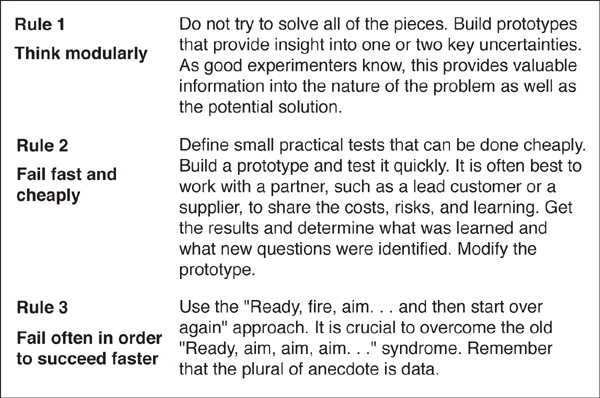

In their simplest forms, prototypes are spreadsheets, process maps, or simulations—anything simple that enables you to visualize and understand better where your ignorance exists. The innovation team must be able to play with, change, and develop the prototype to reap valuable insight from it. Successful prototyping requires attention to three rules, described in Figure 5.5.

Figure 5.5. The three rules of prototyping27

Several companies have successfully used prototypes and the “probe-and-learn” approach to commercialize radical innovations. For example, using prototypes IBM developed silicon germanium devices, and Schwab created electronic trading. Howard Rosen, former president of ALZA Corp., says that undertaking anything innovative, especially in the pharmaceutical industry, requires that you fail a lot. What you want to do is fail fast and cheaply.28 This is the role of prototypes.

Look closely at successful radical innovation, and you will find many prototype precursors. The best prototypes are those that customers and suppliers can play with so that you reduce your ignorance of what they see in the proposed concept. Early prototypes should focus on extreme simplicity and learning the basics. Later, at the second and subsequent levels of prototyping, you can move to more robust, less modular representations of the innovation. More advanced prototypes should focus on the essence of the design. The best prototypes are the ones that provide designers, customers, and suppliers with the opportunity to make sequential improvements. A prototype focuses the team on a common evolving concept: It connects the team with a powerful model that clarifies both the problem and possible solutions. Also, a prototype provides powerful clues to the direction of the next steps in innovation.

Prototyping needs to be a core competency of the radical innovation team. It needs to be a primary mode of thinking and operating for the team. The competency of prototyping requires people who are capable of working with and through incompleteness. Building, testing, refining, refuting, and corroborating prototypes are essential activities because they do the following:

• Challenge the existing mental models of the team

• Uncover patterns of results from which the team can learn

• Pull the team together and create a common, shared vision and language

• Generate a level of excitement that traditional means cannot equal

• Generate new thinking that eventually becomes the radical innovation

Making Deals

Turning good ideas into robust innovations requires that the ideas be changed from bare-bones possibilities to something in which investors can see value. Some great ideas are overlooked because their advocates did not provide a sufficiently compelling picture of the potential attractiveness of the innovation. Instead, the advocates hoped that the value would be self-apparent (it seldom is) or they made inflated projections of the timing and size of the return on the investment, thereby alienating the investors who distrust hype. The process of idea management should include a process step that turns the idea into a sufficiently complete picture in which potential investors can see the real value and risks of investing. This “deal-making” process resembles the investment process that venture capitalists require for their investments under consideration.

Deal making positions key persons in the company as seller and buyer. The transaction is very much of seller and champion taking a deal to the buyer and getting “buy in.” At that point, they are in the deal together. They move the deal forward by changing, accelerating, redirecting, leveraging, mortgaging, or otherwise improving the deal to meet their mutual vision. They also might divest themselves of the deal, garnering the available value and using it to make/further other deals in their portfolio.

The greater the deal flow, the greater the odds of achieving successful innovation because not every deal is destined to be a winner. Deals need other deals with which to combine and fuse. A high rate of deal flow also produces high rates of knowledge transfer among deals and potential combinations among the deals to produce better deals.

Innovation That Fits

Leading companies such as Wal-Mart, GE, and P&G focus their innovation on areas that enhance their core competencies. Knowing your core competencies and innovating on and around them is a key to success. For example, easyGroup, a rapidly growing collection of low-price companies on the Internet, follows a simple formula: Look for services with high fixed costs, price elasticity, and Internet ordering; then create a frill-free offering that gives consumers few, if any, choices. easyJet has only one class of service; easyCar rents only one class of car and requires that it be returned, clean, to the same location. Former easyGroup CTO Phil Jones says, “We don’t aspire to be all things to all people. We do one thing very well at low cost.”29

A company sometimes unknowingly limits the innovation opportunities it considers or chooses by assuming too narrow a range of opportunities that could “fit” the company. Experience has shown that it is foolhardy and a waste of money and time (possibly even value-destroying) to go into businesses where a company has no relevant competencies or relevant experience. History is littered with the wrecks of those types of investments. Vivendi, the French water utility, moved far outside its core when it acquired Universal Studios from the Bronfman family’s Seagram Group. Eventually, Vivendi sold Universal Studios to GE’s NBC unit. That entry and eventual retreat from the entertainment industry cost former chief executive Jean-Marie Messier his job and cost his shareholders dearly.

However, if a company too narrowly defines what fits and what is part of its core competencies (in other words, what business model, markets, and technologies are essential for the company to compete), it may miss important innovation opportunities. What if a company possesses four out of five key technologies required for an attractive new opportunity? Should it dismiss the opportunity because the technology is not currently in-house? Or should it gain access to the missing technology and pursue the opportunity?

The fundamental question is, how close a fit is close enough? Going too far afield is usually a disaster. However, staying too close to the existing is too limiting and loses value creation opportunities. Consider if Apple had decided that the music business did not fit its PC business; we would not have iTunes and iPod. Or if 3M had passed up Post-its because it was not in the business of selling those kinds of products; they were much more comfortable with office products in the form of tapes. Or if Amazon.com had decided its business was just selling books.

Too often companies pass up really good ideas because the opportunities do not seem to be part of their business. Instead, the companies invest in less attractive opportunities that fit their concept of what business they are in. In other words, companies conform to their limited mental model of their business and core competencies instead of seeing what their real strengths are.

The key is to carefully define a company’s competencies and not just focus on the obvious aspects of the business. A company has to look carefully beneath the surface to determine the real competencies and see what innovations would fit. It has to look hard at the identified opportunities to see if the fit is good enough to warrant investment.

Consider Dell’s expansion into servers as a case in point. Dell identified its core competency as managing the Internet-based supply chain. It developed this competency in the PC arena. However, it saw an opportunity to use the same competency in a related business model providing servers. The market for servers was not exactly the same as the PC market, and it required a higher level of service than the PC market, but the business model had many similarities and used the Internet-based supply chain competency that Dell had mastered. Dell chose to enter. To date, Dell has racked up significant market share and revenue growth in the server markets. Now it is looking for other similar opportunities to leverage its competencies in new or related markets.

Management Systems Comparison

A multitude of different types of management systems is used in innovation: stage gate project management, portfolio management, structured idea management, brainstorming, project selection processes (financial and nonfinancial), experimentation, prototyping, product and service rollout, and commercialization processes, just to name a few.

To highlight the different approaches and the range of options, we have identified some of the most important types of management systems and compared the different approaches required for incremental innovation and radical innovation (see Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Comparing Innovation Systems for Incremental Versus Radical Innovation

Management systems vary between companies. No set of systems serves all companies. The processes selected should be determined by the innovation strategy and the balance of radical, semiradical, and incremental innovation in the portfolio.

Senior management should oversee the development and installation of the systems to ensure that they match the company’s needs and operating styles. Then management should monitor the systems’ performance against the objectives. There is no reason to allow a management system to exist if it is not delivering the value expected of it. Management systems can and should be changed and adapted over time to match the company’s changing needs.

Electronic Collaboration

People who need to work together are increasingly separated by distance—partners are in different physical locations, offices in the same business unit are often overseas, there is increased use of outsourcing, and telecommuting is becoming a common mode of work. The negative effects of the separation are often magnified due to mismatches in time zones, cultures, and communication technologies. The online revolution has made it possible for companies to virtually extend the organizational boundaries, overcome the separation, and tap into their customers, suppliers, and partners.30 This electronic collaboration is a new, important element of innovation management.

Boeing is an excellent example of a company that has removed the distance that traditionally separates teams. The airline giant put together a computerized engineering system that wired suppliers, manufacturers, engineers, and even some customers into the development process. The result was the Boeing 777, whose CATIA and EPIC design systems (electronic design collaboration tools) have revolutionized product development. It was the first airplane designed without physical mock-ups. The design and commercialization process was faster, better, and cheaper—and it was made possible by a web-enabled collaboration that linked the different participants into a virtual design room.

In addition, open source software-development projects have become an important economic and cultural phenomenon. Source-Forge.net, a major infrastructure provider and repository for such projects, lists more than 10,000 projects and more than 30,000 registered users. The digital software products emanating from such projects are commercially attractive and widely used in business and government (by IBM, NASA, and others). Because such products are deemed a public good, the open source movement’s unique development practices are challenging the traditional views of how innovation should work.31

Eli Lilly launched an online knowledge broker called InnoCentive (www.innocentive.com), where it and other firms post R&D problems and solicit solutions from companies and individuals worldwide.32

The packaging company Tetra Pak was having unsatisfactory results in idea generation and product development, despite great effort. After examining cultural and process issues, the company instituted an Internet-based management system for product creation. The new system helped Tetra Pak reduce product development lead time by 40%, and the company’s yield of successful products climbed. What made that significant step change possible was the significant increase in decision-making speed. Tetra Pak not only wired the key decision makers together, ensuring that the right people were involved at the right times, but it also provided improved tools for decision making and knowledge management that gave increased abilities to the enterprise teams. For Tetra Pak, the benefits came from a better system that resulted in faster and better decisions and implementation.

APTEC, an engineering and design company located in Florida, used electronic collaboration tools to produce a new wireless headset for DaimlerChrysler in record time without a single face-to-face meeting. The product was on budget and schedule and met the rigorous quality requirements of the client. This was the first time the product had been produced, and the team included partners located in the United States, South Korea, and the Philippines. They used electronic collaboration tools that allowed real-time, three-dimensional codesign. They harnessed the ability to manipulate models through iteration after iteration among the innovation partners. This resulted in significantly reduced program costs (zero travel costs, real-time and highly efficient project review meetings) and lightning-fast innovation. And all partners—including the customer—could review the design options and decisions.

GE Plastics developed an electronic collaboration approach to sharing product-creation knowledge across the entire organization and beyond, to employees, customers, suppliers, and so on. GE Plastics’ results are stellar: The average time to close new target customers dropped from one year to 90 days. Also, more than 80,000 registered users turned to GE Plastics’ new Design Solution Center in its first year, driving $1.5 billion in new revenues. New online training seminars have replaced costly in-person seminars that entailed sending managers around the country, saving more than $2.5 million in the first year.

Management Systems and the Innovation Rules

It is not enough to have a vision or preach about the need for innovation; companies need to use systems to achieve innovation. Management systems are the key to balancing the sometimes antagonistic aspects of innovation. Systems must be combined so that they can manage the dualities of the following:

• Technology and business models

• Radical and incremental innovation

• Creativity and value capture

• Networks and platforms

The unifying factor for systems is the innovation strategy and portfolio. The management systems a company chooses should flow directly from its choice of innovation strategy and balance it seeks in its portfolio. Consider how different Dell’s innovation systems must be from Apple’s—one focused almost exclusively on business model innovation and the other delivering a combination of technology and business model innovations. For Apple, one of the keys is to keep the technology and business model innovations in coordination. For Dell, improving the business model is the primary role of the systems, and managing technology is secondary.

The management systems should also provide for parallel creativity and value capture in the organization. In particular, the systems should allow a seamless blend of idea generation, selection, and execution by the network of innovators inside and outside the company. Properly functioning systems provide active creation of innovations—through ideation, selection, development of ideas, and efficient execution and commercialization—through careful development of innovation prototypes and the development of commercially viable changes to the business model or technology.