Chapter Four. The Core of a Successful Brand Strategy: Breakthrough Products and Services

At the core of any brand strategy is the successful experience of using a product or service. Identity, advertising, and distribution cannot correct the failure of a product to perform as expected. Thus, as this chapter discusses, all members of product development teams must understand and participate in brand development. Customers purchase breakthrough products to support their lifestyle values. They also identify with companies that represent values compatible with their own. Developing a successful product brand begins with understanding your customers’ values and connecting that awareness to the broader goals of your company’s values. Those values are then captured in a unified strategy. The strategy, often articulated as a mission statement, flows to programs, products, and satisfied customers. This chapter presents ideas and methods to build and support both corporate and product brands, and it highlights products that have successfully achieved this.

Brand Strategy and Product Strategy

We have established the fact that the best product opportunities materialize from emerging trends that are the result of changes in the SET Factors. These changes generate Product Opportunity Gaps (POGs) that must be broken down into Value Opportunities (VOs). VOs must be then translated into product features and style. The process of identifying VOs and converting them to product characteristics begins with a corporate and product brand strategy, the focus of this chapter.

If new companies establish their brand by accident rather than by design, reinventing or cleaning up the brand later becomes expensive and difficult.

One of the most powerful forces driving contemporary businesses today is the development and management of brand. Graduates in MBA programs study brand, and many consulting firms are experts in advising companies on brand. Other core disciplines in the product development process also need to be aware of the relationship between a company’s overall brand strategy and how that affects the new products it develops. In addition, the products that a company markets both deliver and define the brand, regardless of whether a strategy has been defined. In small, emerging companies, it is important to understand that the first products developed establish the brand of the company. If new companies establish their brand by accident rather than by design, reinventing or cleaning up the brand later becomes expensive and difficult. BodyMedia started the right way and built naturally, but not all companies have that foresight. Interdisciplinary teams need to have a shared vision of the brand when developing products. The vision needs to balance the everyday expectations of the customers in the intended market with the longer-term strategy and mission of the company. Imagine if Apple’s electrical and mechanical engineers did not buy into the commitment to design the original transparent iMac. Equally important was the need for the manufacturing engineers to commit to the quality needed to produce transparent and translucent parts without flow lines. The industrial designers also needed to design parts with a clear understanding of the visual effects of the interior components. All of these groups needed to work in unison to deliver an aesthetic result that was flawless in execution and that built on the brand history of innovation and user-friendly personal computers that the Apple II and Macintosh had established two decades earlier.

Apple’s integration of design, engineering, and brand continued in every product it has produced since. The iPod, iPhone, and iPad all have a consistent brand strategy that starts with Apple’s focus on intuitive interface design, as well as a strong influence from the visual form language of Braun products developed decades ago under the direction of Dieter Rams. Apple engineers have been able to work with programmers to design hardware that requires less energy and allows for longer battery life per day. The core product you interact with is connected to a series of services that are all easily accessed on the interactive screen on each product, an interaction that is consistent across all products.

A company’s products should reflect the brand decisions a company makes. The Aeron chair, which redefined ergonomic and aesthetic expectations in office seating, makes a major statement about the brand of Herman Miller. The company chose to produce a chair based on ergonomic comfort instead of one based on a traditional office hierarchy. This decision is a clear statement that Herman Miller supports—literally and figuratively—the concept of lateral management and comfort over rank. The name Aeron, like the chair itself, is equally contemporary and ethereal. A decade later, it is still a successful chair and Herman Miller has released several new designs. The Mirra Chair has also been a successful evolution in breathable seating at a lower price point and in one size.

D. A. Aaker describes brand identity as “a unique set of brand associations that the brand strategist aspires to create or maintain. These associations represent what brand stands for and imply a promise to customers from the organization members ... by generating a value proposition involving functional, emotional or self-expressive benefits.”1 Aaker further shows how the product is core to the brand, yet the brand is more than the product alone.

Where does a company’s brand value and identity reside?

• Is it in the goals and mission statements that flow from the CEO down through management to particular divisions, programs, and products?

• Is it in the products and services that a company offers and produces?

• Is it in the corporate identity, advertising, and public persona that a company adopts to communicate its message to the public through formal and informal media channels?

• Is it in the experience that a customer has when interacting with the product or service?

• Is it in the perceived success of the company by investors, stockholders, and the economic community-at-large?

The answer to all of these questions is, yes! Many companies, however, often focus on one of these over the others. They fail to see that the branding process is a cycle that must be constantly monitored and ready to react to change. A product or service is integral to maintaining the brand value of a company. When a company produces products that are consistent with the brand strategy, all aspects of the brand work in unison to effectively compete in the marketplace. However, the failure of a product to communicate the brand value of a company to a customer can negatively affect the brand image, and no other channel can successfully offset that effect. A strong advertising campaign cannot offset a bad product, nor can updating an identity program overcome a poorly conceived product. If a company learns to build a message around the relationship between its customers and its valued product (the product experience), everything else flows from that. The brand, values, and relationship to the customer should all be represented in the mission statement of a company and in the brand identity of its products.

Brands must build on a core tradition and adapt to the current SET Factors. This was a major factor for Navistar in developing the LoneStar (see Chapter 9, “Case Studies: The Power of the Upper Right”). One of the oldest companies in America, Navistar had a long tradition of producing durable products for middle America. However, the brand lost its luster as the company focused on cost reduction in the second half of the twentieth century. At the turn of the century, the company reinvigorated its brand by reading the SET Factors and delivering innovation that introduced new capabilities while also addressing the changing needs, wants, and desires of the driver. Yet at the same time, it maintained its tradition of American values. The LoneStar was the first product introduced to be the lead statement for the new brand strategy. It redefined the expectation of a sleeper cab designed to haul goods across the country with power, aerodynamics, and fuel efficiency. It also redefined the drivers’ perception of truck style and internal comfort designed for the on-the-road 24/7 lifestyle.

A successful product must connect with the personal values of customers. A product experience includes both the expression of the product and the interaction with the product. Customers are looking for three basic things from a product that will improve their lives:

1. Is the product useful? Does it enhance some activity or allow them to accomplish an activity that is important to them?

2. Is the product easy to use? Does it stay consistent in use throughout the expected life of the product?

3. Is the product desirable? Does the product respond to who the customers are as people and complement how they want to project themselves to others?

P&G accomplished this type of breakthrough in the redesign of Herbal Essences. The understanding of SET Factors for Gen Y women gave P&G an opportunity to rethink the category. The design of a new package shape created a clear visual connection to both shampoo and conditioner, making it stand out at point of purchase with useful contours that comfortably fit in the hand even when wet. The use of color and creative descriptions created subcategories for particular types of hair, making it desirable. The development of new combinations of hair chemistry delivered on usefulness through performance attributes of hair in daily life. These same issues exist in complex products. A truck is useful if it allows you to deliver goods from one place to another in a timely fashion. Some trucks are easier to use than others; some have controls and settings that are easier to adjust to particular sizes and preferences (for example, some are designed to be rented for a day, whereas others require a different grade license and training). People who drive long distances also want a truck that is more like their home; many who own their own big-rigs modify the interior because, before the LoneStar, no truck had the comfort and features of their own home.

The more complex the product and the larger the company, the harder it is to deliver on these three simple objectives. Developing a useful, usable, and desirable product that creates a meaningful connection between the identity (brand) of a company and the personality and needs of a customer is hard enough. Creating that relationship and making a profit is the major challenge. Finding the position between mass production with low margin and smaller-run niche markets at higher profit margins is a challenge companies must contend with. How low can Mercedes go with the cost of its cars before it negatively affects this brand of exclusivity? How can Hyundai get into the higher-price markets and extend its brand out of economy?

The product, the customer, and the product experience must be the core throughout the whole company. For teams to succeed, they must:

• Focus on a shared, consistent understanding of who the customer is

• Respect one another and recognize how each area of the company contributes to the product experience for each and every stakeholder

• Recognize that their approach, attitude, and end product all form the basis for the product and corporate brand

• Recognize that the value base and affiliated qualities the customer seeks must drive the product development process

In The Brand Gap: How to Bridge the Distance Between Business Strategy and Design,2 Marty Nuemeier discusses the fact that many companies do not recognize the role of the customer in defining their brand. Nuemeier says that brand is not what the company thinks it is, but rather what “they” (the customer) say it is. To build and maintain brand value, Nuemeier describes five essential activities: A company must differentiate from the competition; collaborate across the company, with its specialists, consultants, and customers; innovate in how it presents and delivers the brand to its customers; validate the brand to make sure it appropriately resonates with customers; and cultivate the brand to grow in a dynamic way. If the product, customer, and product experience remain core to a company, the brand will connect and evolve with SET Factor changes. Managing brand is the job that never ends; it is just a question of when to make evolutionary changes and when you need to be revolutionary.

Corporate Commitment to Product and Brand

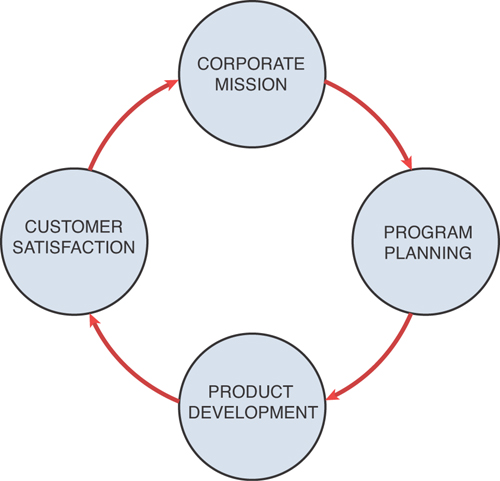

The development of products and services in the Upper Right requires a commitment at all levels of the company, from the CEO, to middle management, all the way to the engineers, designers, marketing and finance personnel, and others responsible for actually creating and producing the product. As Figure 4.1 shows, four fundamental levels to this commitment feed back and continuously refine the process for the company. First is the corporate mission itself, the strategic goals that drive the company’s long- and short-term goals. From that mission statement, program planning takes place, where the goals and resources of a product development program are defined. Next, product development takes place, with the outcome being a product or service that will be sold to a target customer group. If the product meets or exceeds customers’ expectations, they will be satisfied. And if customers are satisfied in a true sense—the product is useful, usable, and desirable—the product will sell and be profitable for the company, fulfilling and reinforcing the main goals of the corporate mission.

Figure 4.1. The cycle of product development, from corporate mission to customer satisfaction.

If the process succeeds and customers are satisfied, then shareholders and investors make money and they, too, are satisfied and further reinforce the corporate mission. If the process fails, then investors, often impatient and unforgiving, might require a change to the corporate mission and management. All too often, companies focus on cosmetic changes to keep shareholders happy. Ironically, companies that instead focus on the product, with the goal of creating a highly valued product, maintain the long-term satisfaction of the shareholders.

Program planning is critical to the overall process. It is this level of middle management’s responsibility to translate the goals of the CEO or president into a successful product in the marketplace. When programs are over budget, are late, or fail to meet profit targets, this level of management usually is to blame (or is given the blame). Thus, a coherent process and approach to managing that course of action improves the chances of a product succeeding in the marketplace.

To develop a product within the mission of the company, the entire organization must have a consistent view of the brand strategy. Because a number of individuals and levels in a company affect the brand message, experiencing a break in the continuity of communication is easy. Product planning groups at the upper level of a company might not have a clear communication channel to the teams developing the products or the customers they are designing for. Outside consultants can be in conflict with internal working groups. Advertising companies might design the look and feel of an ad campaign without contact with the product team. A consulting firm might design a logo, Web site, or support literature without any contact with people working directly with the product. We cannot emphasize how important it is to have a shared vision of the company and the customer and to maintain an open dialogue early in the process. Keeping key decisions consistent and sequenced appropriately is also important. Deciding on a name or graphic identity could be premature until the product characteristics are clear. Committing to an arrangement and number of features might occur too early and force major engineering changes downstream. The visual aesthetics cannot be decided until it is clear that the form connects with the lifestyle image of the intended customers. All of these decisions put tremendous pressure on middle management to regulate the flow of information up and down the levels of a company and into and out of the company between inside groups and outside consultants and suppliers. It also puts pressure on a process of creating parallel decision paths that must integrate at each critical phase.

To develop a product within the mission of the company, the entire organization must have a consistent view of the brand strategy.

This is true for large, established companies as well as for small startups. A small company has no middle management, but the effort to project the brand and understand the implications of the initial product on the brand is critical; the initial product is the brand. Yet the reality of startups is often that the product is usually developed first and is often the only focus, given limited resources and the need for revenue. Taking the time to define the corporate mission and plan the product to deliver on that mission allows the company to strategically and thoughtfully define its brand up front instead of having to attempt to redefine it later. As a startup, BodyMedia had limited resources and needed to develop its first product while moving toward production. However, the company took the time to define its long-term strategy and develop a plan to get there. BodyMedia created a company logo and product aesthetic, and maintained a focus on ergonomics and comfort in its very first product. As the company followed its strategic plan—even if that plan matured and changed over time—it had a consistent approach to developing the brand, which aided the product and company awareness in the clinical and then consumer markets.

The process from corporate mission to customer satisfaction begins with a corporate strategic commitment to the process found in both the philosophy of and structure for product development. The philosophy is found in the brand identity of the company and its products. The structure is found in an integrated new product development (iNPD) process that puts the user in the center.

Corporate Values and Customer Values

A company’s brand identity relates to the values it represents and how they resonate with its customers. As Chapter 3, “The Upper Right: The Value Quadrant,” discussed, consumers need to connect their product purchases with their own personal values. When a product does connect, customers are willing to pay a higher price and/or are more likely to return to the company for the next purchase. Everyone has two distinct types of value systems. One acts on a broad social level; the other is personal. Although they are often connected, they need not be. In general, a company’s overall actions connect with the broad social values, while the products and services it provides connect with the personal values. Chapter 3 discussed the Value Opportunities that enable a product to enhance a user experience with the product through personal values. However, a company’s values can also have an impact on the perception of its products. Nike went through a tough period not because the products lost their value, but because Nike lost its perceived value as a result of its cheap labor practices. Kathy Lee Gifford’s clothing line was attacked for the same reason. Tobacco companies are trying to impress customers with their altruistic commitments to offset their public image. Many antismoking factions felt that the Virginia Slims Tennis Tournament was hypocritical by supporting both women’s independence and promoting a product that many consider to be the fastest-growing cause of death in women. Being a good corporate citizen helps create a broad context that supports a positive feeling in consumers. People purchase products that enrich their experience based on what is important to them—their values. Both the product and the company must support that value base.

In her book SuperCorp: How Vanguard Companies Create Innovation, Profits, Growth, and Social Good,3 Rosabeth Kanter states that leading companies today must have a triple bottom line for their consumers and shareholders based on the 3 P’s of people, planet, and profit. Companies need to demonstrate that their footprint in production and post-product use have little or no impact on the environment. Companies must also show how they are supporting a humane production process in the way they treat employees all over the world and what else they do to support charitable organizations through direct actions or by supporting and giving time to employees to make their own choices. This must be maintained as companies look to the profit shareholders expect from their investment in the company. The concept of people, planet, and profit is now part of the brand challenge for companies. Some are doing a great job and confronting it directly; others are more smoke and mirrors. Consumers have ways of finding out who is genuine and who is not—and once they do, they broadcast the result through the Web and other channels to others.

As Chapter 3 discussed, people are dynamic—and their value system is too. The most successful companies learn to anticipate trends and make changes while staying true to their core mission and identity, and they can maintain or increase customer loyalty. These companies understand how interconnected these brand attributes are. The better the brand attributes are coordinated, the better the company performs. A successful brand strategy integrates the profile of the company with its products and creates a customer experience that both is consistent with the corporate message and inspires brand loyalty. Any message that a company communicates through formal advertising or through cultural interaction and support must also be consistent with the core company–customer relationship.

Managing Product Brand

Product brand management is an art and a science. Product programs must be managed using a cross-platform approach, making sure all aspects of a product are maintained in the right balance of technology, human factors, and style. Products must be distinct in the market against direct competition while also maintaining a clear continuity with other products in the line of products it connects to. Apple products connect, while Sony products do not. OXO has maintained its brand continuity even though the company has produced more than 850 products. Any one OXO competitor only competes among a subset of its products. Finally, brand managers must be in constant dialogue with corporate strategists navigating the SET Factors to directing change at the corporate level.

Building an Identity

In some cases, a product becomes the basis for a new company. In other situations, new products are developed within an existing company. Companies can consider a variety of alternative strategies when developing a brand identity for a new product:

• How a new product can become the basis for a new company

• How a new product in an existing company can spawn a new division or line of products

• How a company can develop a new and broader identity

• How a company can use a flexible identity connecting a core across all products, but also making each product unique

• How a company can develop an aesthetic that becomes so powerful that it spills into other markets

The case studies referred to in this book represent many of those approaches. In the case of OXO and BodyMedia, a new product can become the basis for a new company. On the other hand, Navistar, Crown, and Steelcase were each established companies that spawned a new division or line of products with the development of the LoneStar, the Wave, and the Node education seating system, respectively. Starbucks brought attention to its product and service through an entire identity system across the company. In the case of Starbucks, a flexible identity allows each coffee roast to take on its own identity while keeping a constant core logo and style across products. Many auto companies produce a product to introduce a customer to the entire company, as was done with VW and the new Beetle, Mazda and the Miata sports car, and Nissan and the electric Leaf. VW’s approach creates a symbol for a secondary product, such as the laser-cut key, by bringing it through the entire line of VW and Audi and creating a strong identifier for the company, much as the Coke bottle is a symbol for Coca-Cola in the soft drink industry. In the case of Steelcase, which worked with IDEO in developing the Node, as discussed in Chapter 9, the product introduced an entire new line of products in the education market, broadening the brand to this new opportunity while maintaining its identity of innovation and quality in seating systems. Other companies have effectively created such a powerful aesthetic that it spills into other markets. For example, time and time again, Apple products define the cutting-edge aesthetic for consumer-based technology products. Now every time a product is seen to resemble an Apple product, even if not made by Apple, it reinforces the brand value of the company and generates free advertising for Apple. Some of these approaches are explored more fully next.

Company Identity Versus Product Identity

When developing new products, the relationship of the look of a product to other products produced by the company is critical to consider. In doing so, a company might choose between two options, one to maintain a strong role in the corporate identity or the other to allow the product brand to overshadow the company identity.

DeWalt products have a consistent use of graphics, color, and finish across the entire line. All DeWalt products use yellow, black, and silver. Most of the products have yellow as the primary color, silver as the second, and black for the logo and details. A few specific products reverse the emphasis for effect and use black as the primary color to promote their unique attributes. The products are instantly recognized in stores. The DeWalt brand identity extends their trade dress to an entire line of products, from compressors, to drills, to radios.

UPS, discussed further in Chapter 8, “Service Innovation: Breakthrough Innovation on the Product–Service Ecosystem Continuum,” has developed a strong brand identity around its logo and a strong trade dress around its use of the color brown. “What Can Brown Do for You?” not only captures UPS’s approach to customer satisfaction and innovation in package delivery and logistics, but also reinforces UPS’s use of the color brown. There is a consistency in everything that UPS presents to the public, with a consistent use of the logo and the color brown on trucks, planes, uniforms, and shipping envelopes, making UPS one of the most recognizable brands across the globe. In services, a consistency across every touch point, such as product graphics, packaging, employee attire, and any digital interaction screens, is required to communicate the brand to the customer. UPS is still building on their co-brand strategy for the two main components of the corporation. The focus on the word “logistics” allows them to emphasize both the package and informatics capability. They have also developed several strategies since “What Can Brown Do for You?,” such as the white board animation, to focus on their pick up, drop off, and delivery services.

When Crown developed the Wave personal lift device for warehouse pick-and-place tasks (discussed further in Chapter 11, “Where Are They Now?”), it chose to give it a unique identity to fit the context of use. The name, Wave, is the primary identity. The Crown logo, also used on all the other lift products, is downplayed (see Figure 11.6). Wave is actually an acronym that comes from the more technical development name, “Work Assist Vehicle;” it was chosen to give a less serious identity to this new line of products. The graphics, manuals, video, and Web site are all built around this decision. The color of the vehicle is primarily white and gray, with the option of bright colors for details. The Wave logo is also portrayed in a more vibrant color and expressive typeface, a departure from the subdued colors of the other Crown products. Crown has also added a new sales force specifically for this product.

The brand identity of the OXO line of products is based on the interrelated ideas of a comfortable and strong grip, universally accessible products, and a sculpted handle of black Santoprene, which becomes the signature material that expresses the brand. All of the OXO products are designed using a contemporary aesthetic that combines visual sophistication with perfect tactile properties to create a secure, comfortable, and confident experience. The logo is clean and simple, easy to recognize from a distance, and easy to remember; it also reads the same way backward and forward. OXO has developed its reputation primarily by word of mouth, the most cost-effective and positive type of advertising. Yet OXO’s identity is also more abstract, in that customers expect ergonomic, easy-to-use, and clever products.

The brand identity for Margaritaville is Key West subtropics and fun. The use of color accents across a primarily brushed and shiny metallic-like finish, along with both subtle and pronounced nautical symbols integrated in the Frozen Concoction Maker product, communicates that identity. Every detail continues the identity into the experience of use, including the clearly drawn treasure map on simulated brown parchment as a quick-start manual, nautical charms for margarita glasses so that guests know which drink is theirs when getting refilled, and the salt rimmer, a must for the frozen margarita. A consistency across the larger Margaritaville brand connects the product (both the Frozen Concoction Maker and consumables such as margarita mix), its communication, its environment in stores and restaurants, and its interaction (for example, on the Web); see Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2. The Margaritaville Brand Experience.

(Courtesy of Altitude and Jarden)

Another approach to maintaining a separation between products but keeping a core connection to the parent company is through a flexible identity. Here a theme is maintained between products with a strong reference to the parent company, yet each product also has its own unique attributes and identity. Starbucks uses this approach to differentiate each of its roasts, yet with a clear statement that they are all part of the Starbucks family. Each roast has its own name, along with a unique icon, but under the same basic style, with the company’s Starbucks logo placed consistently against the clean background.

Relating the company and product brand to the core needs, wants, and desires of the customer can convert a failing company into a market-leading success.

A recent approach to constantly updating products to stay with current trends is known as postponement. The traditional approach to product development is to determine up front all varieties of a product that will be offered. After the molds are made and the colors decided, the product remains unchanged until the next model is produced. With the emergence of rapid manufacturing techniques and the ability to make shorter manufacturing runs affordably, a company can postpone detailing decisions until just before the product’s release. Doing so enables a company to keep style details current on a continual basis. The approach also allows for more frequent changes in products. Swatch began the trend with interchangeable watch faces, bands, and hands. Nokia used the approach to allow customers to choose from a wide variety of covers on their cellphones. Postponement allows for different product models within a core product and brand. The variety of styles available to the customer allows each user to customize the product based on personality. This feature tends to add considerable value to a product, pushing it further to the Upper Right. People will pay for value, so, in addition to allowing for variety within a brand, postponement tends to command high profit margins for these interchangeable features.

Building Brand Versus Maintaining Brand

Brand must be built and maintained. Connecting to the customer enables both to take place. UPS has long-standing brand identity; it has made the right changes to keep up with or stay ahead of the competition. FedEx, in comparison, is a newer brand that had to establish itself right away. It went from obscurity to high international recognition in a relatively quick period of time. You likely can easily recall the brown trucks of UPS and the bold purple and orange of the FedEx logo, but you use their services because you can rely on the companies to deliver what you send on time and to the intended recipient. In comparative terms, UPS is the seasoned professional and FedEx is the young upstart. Both are equally respected. One quickly built a powerful brand identity; the other has successfully managed long-term brand equity. We examine the brand strategy and growth of UPS further in Chapter 8.

This subsection examines three case studies, one in which a brand is built up, one in which an established brand is reinvigorated and redefined, and one in which an established brand is maintained. In the latter two cases, relating the company and product brand to the core needs, wants, and desires of the customer converted a failing product or company into a market-leading success.

Starting from Scratch: Cirque du Soleil

Cirque du Soleil is a well-recognized brand that connotes sophisticated style, theatrics, music, colors, and, of course, sheer talent. The current global brand is a hybrid synthesized from a variety of forms of international entertainment from classic and traditional categories to urban street-performing entrepreneurs.

Cirque du Soleil was started in 1984 by former street performers Guy Laliberté and Daniel Gauthier. Their brilliance was to recognize the white space between circuses like Barnum and Bailey and the entertainment that adults sought. Instead of featuring elephants and tigers and clown after generic clown coming out a car, Cirque du Soleil developed a “transdisciplinary experience” that blended circus, theater, live music, song, and costume. If you examine the VOA of Cirque du Soleil against the VOA of Barnum and Bailey for the adult audience, you see the strong sensuality, adventure, power, and independence emotions; the visual and auditory aesthetics; the unique identity; and the quality craftsmanship consistent in every show and every piece of merchandise. Cirque du Soleil is also strong in social VO for its commitment to social action—for example, the group works with youth at risk and founded ONE DROP, which fights poverty by providing access to water and sanitation in developing countries. It is not unreasonable to pay three times the cost of a ticket to Barnum and Bailey to see a Cirque du Soleil performance.

Although theatrical and musical, Cirque du Soleil still connects to and pushes the boundaries of the circus. Although many of its shows are permanently placed in theaters, its traveling shows are often found in tents that are traditionally decorated in bright blue-and-yellow sweeping stripes. Each unique show is completely developed in-house, true to the group’s mission to “invoke the imagination, provide the senses and evoke the emotions of people around the world.”4 Cirque du Soleil also articulates a set of values:

• “To uphold the integrity of the creative process

• To recognize and respect each individual’s contribution to the body of work

• To extend the limits of the possible

• To draw inspiration from artistic and cultural diversities

• To encourage and promote the potential of youth”5

Every show results from a collaboration among the performers, the designers, the engineers and technical support, and the business unit.

Cirque du Soleil has built a brand from scratch, one recognized across the world and based on collaboration, social responsibility, and sophisticated entertainment.

Redefining a Brand: Herbal Essences

This example is about rebuilding a brand that had name recognition and longevity but lost its luster. For P&G, it is all about the first moment of truth. Given a competitive purchase environment, P&G wants to produce the package and product that you will choose every time. The role of packaging has expanded, and P&G has been equally innovative in seeing packaging as a powerful way to express brand identity and deliver on the second moment of truth when you use the product. The design of a package can play a major role in helping customers through that process of use, and can complement the customers’ lifestyle. P&G’s goal is to build billion dollar brands and it seeks to be no. 1 or no. 2 in every category in which it competes. This is the perspective that drove the rebranding of Herbal Essences. Susan Arnold, then Vice Chair of Global Beauty and Health, took the risk to redefine the brand in record time. A. G. Lafley, then CEO, commented in his book The Game-Changer: How You Can Drive Revenue and Profit Growth with Innovation, “About eighteen months later the new Herbal Essences was back on the shelves and put the brand back on track to eventually become another P&G billion dollar brand.”6

Herbal Essences is a multifaceted example in the creation of a breakthrough product. It is an excellent case study to highlight P&G’s commitment to innovation. The process used in the Fuzzy Front End was part of P&G’s commitment to support innovation in every part of the company. The process started in Clay Street, an off-site P&G innovation incubator, discussed in Chapter 6, “Integrating Disciplines and Managing Diverse Teams.” The cross-functional team in Clay Street recognized the SET Factors for shampoo for Gen Y women and allowed the company to find an untapped Product Opportunity Gap. The commitment of management allowed it to get the product through the pipeline in half the normal development time. In spite of the pressure of time to market, the company held on to the highest standards of execution. Chemical engineering delivered on the shampoo and conditioner performance attributes to create new chemistry. With several new subthemes, the chemists had to develop different formulas for each shampoo and conditioner set to support the results stated on the package.

Two consulting firms, LPK and Ziba, worked with the P&G in-house designers and marketing to develop the package (see Figure 4.3). LPK, a brand firm based in Cincinnati, Ohio, was primarily responsible for developing the overall brand and sub-brand scenarios for Gen Y women. Ziba, located in Portland, Oregon, was responsible for the design of the form, material choices, and function of the packaging while working with P&G packaging engineers. The sculptural packaging shape was a new look on the shelf and allowed the shampoo and conditioner to nest in the shower and be easy to identify with your eyes closed. The result created a shelf presence at point of purchase, the first moment of truth, with immediate impact on positive growth of sales and total redefinition of the product. According to Ziba, sales increased $30M in the first year.7 According to LPK, for Herbal Essences, the firm found that “the right combination of verbal wit and bright, juicy color created an engaging identity and re-established its relevancy.”8

Figure 4.3. Herbal Essences containers.

Herbal Essences Shampoo has been in existence since the 1970s; P&G purchased it at the end of the 1990s. This case study is an interesting combination of both evolution and revolution in innovation. Clearly, the brand of Herbal Essences has changed to meet the SET Factors. The difference in this rebranding effort is the complete restructuring of the value platform. Other than the name, there is a complete break from the two previous brand concepts, and it became the beginning of a new product system for P&G. Unlike the current VW Beetle, which is a retro-future design drafting off the original, the current Herbal Essences allowed P&G to start fresh and deliver value to Gen Y women. After the new platform for the brand was created, Herbal Essences shifted into an evolution-based innovation, building and extending new products in each persona and creating new extensions, such as Set Me Up Stylers. Ten types of shampoo exist, with up to five varying products in each theme, and the brand is sold in more than 30 countries, with variations to meet the unique requirements of each new cultural context. On P&G’s Herbal Essences Web site, you can find the shampoo that matches your personality and can produce the hairstyle you want.9 The message for women: It’s not just about how your hair feels, but how it makes you feel.

Maintaining an Established Identity: Harley

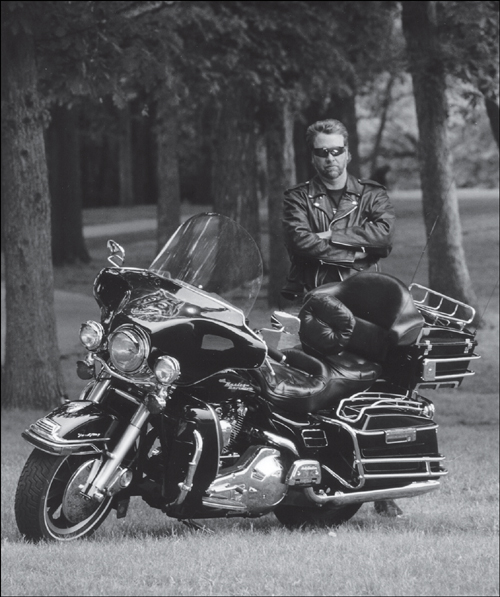

The Harley-Davidson motorcycle is synonymous with the American ethic of individual freedom and escape. It is not just a product; it is a lifestyle and is representative of a global subculture. The life experience of owning a Harley can be complemented by owning the apparel that goes along with it. Once Harley understood the connection, the company became a lifestyle company with a motorcycle as its symbol. A couple in France won a contest that allowed them to pick any location in the world for their marriage. They chose to be married at the Harley-Davidson Corporation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Not too long ago, Harley faced extinction. During the last few decades, it has risen like a phoenix and forced every other motorcycle company in the world to respond to its classic design features. These features (shown in Figure 4.4), which include the fenders; the 45° V-twin, four-stroke engine; the seat; and the handlebars; have been codified by Harley owners. Harley does not change a bolt on its design without the full support of its customers. The company stays in constant contact with its loyal customer base by holding major rallies annually where the company employees mix with its customers. This form of customer connection, a type of ethnography discussed in Chapter 7, “Understanding the User’s Needs, Wants, and Desires,” involves everyone in the company, not just marketing. Harleys previously had a strong identity but a poor record of performance. By slightly adjusting the identity from “rebel without a cause” and biker violence to freedom and escape from the 9–9 rat race, the company responded to a new trend in society. By taking ownership of their manufacturing process, Harley employees were able to reinvigorate the brand identity and produce a higher-quality motorcycle. They managed to improve performance and keep the original look and feel.

Figure 4.4. 1994 Harley-Davidson FLHR motorcycle.

(Reprinted with permission of Jim Dillinger; photo of Dillinger with his 1994 Harley-Davidson FLHR by Larry Rippel.)

Harley does not just manufacture motorcycles. The motorcycle is the core of the company brand and has generated a range of lifestyle products that consumers use to re-experience the feeling of owning and riding a Harley. Harley stores were redesigned to sell clothing and gear. They have been so successful that the company makes more profit from its lifestyle products than it does by selling motorcycles. Honda, BMW, and all the other competitors have been forced to create their own version of the Harley Hog. A design created more than 50 years ago is outselling all the ergonomic, aerodynamic forms developed in the last two decades. When a biker rides a Harley alone or in a group, he partakes in a fantasy experience. The combination of the sound, the wind, the look and feel of the Harley, and the attire projects an unmistakable message about the values of the rider. Brando, James Dean, and Peter Fonda are always out there with them.

Harley found many younger buyers were attracted to the Japanese speed bikes from companies such as Yamaha and Honda. They responded by creating the V-Rod, a radiator-cooled speed bike introduced in 2001. However, to maintain the unique Harley identity, the company spent significant extra development time to give the V-Rod the consistent Harley look, with a V-twin engine, teardrop fuel tank, cupped seat, circular headlight, and triangular frame.

Brand and the Value Opportunities

Remember that a brand is communicated to the customer through a value proposition. This communication must ultimately be articulated through the semantics of the product—that is, the attributes and personality of the product as seen by the user. The way a company chooses to develop and implement the Value Opportunities ultimately defines the semantics of the product and its associated brand characteristics, resulting in that value proposition. All products can be measured using the VO attributes we presented in Chapter 3. It is important to note, however, that all of these opportunities are in constant flux as the SET forces change. As one company interprets the SET Factors and considers the VOs during product development, another company might have a different interpretation and develop a very different product. Identifying the Value Opportunities attributes and then trying to respond to them individually is not enough; instead, the company must examine the VOs as a set in the context of the SET Factors. Each POG that evolves shifts the relationship and possible interpretation of the VO attributes. The VOs must be integrated with a company’s existing brand strategy, and the company must recognize how their interpretation changes the future strategy. Interpreting the VOs is part art and part science. It requires developing insightful concepts and testing and refining those concepts against the issues established in the research phase with core customers. Integrated teams create integrated concepts and can more easily interpret and modify concepts in a coordinated way that synthesizes the style, features, ergonomics, technology, manufacturing, and cost. As the product defines the brand, so the VOs define the product. Thus, Value Opportunities are closely tied to the brand identity of the product.

Remember when computer terminals were covered in bent sheet metal? Most were gray, with a few black ones interspersed throughout the industry. Apple changed the whole look of computers with its large, one-part, aesthetically refined plastic covers. The brand strategy got Apple back in the game and was the first step in a decade of continuous brand evolution under the Apple i strategy. When the Apple iMac debuted, the company was the consumer-loved underdog; now it is the big dog with sales of iPad and iPhone making it one of the most innovative and economically successful companies in the world. The first iMac pushed the concept of plastic to a new level by introducing the use of clear and translucent colors. This was driven by advances in molding and affordability of emerging methods, competition, and social interest to make computers fit into everyday life in the home and office. The VOs for the original iMac included the following:

• Strong emotional attributes of independence, confidence, and power

• Visual, auditory, and tactile aesthetics

• Comfort and ease of use in the ergonomics VO

• A very strong point in time, sense of place, and personality identity

• Social impact in its ability to more readily connect people to the Internet

• Strong core technology and quality VOs

All of these VOs are akin to people’s perception of the iMac, and together they define the brand. Interestingly, most, if not all, are consistent across all of Apple’s products more than a decade later.

The brand of a product (as opposed to a company) needs to be developed based on the character of the product and how it communicates value to the intended market. This involves the look and style of the product as represented by the aesthetics and identity VOs, the physical interaction with the product (the ergonomics VO), the psychological interaction with the product (the emotion and impact VOs), and the performance features through the core technology and quality VOs. The product must communicate brand value throughout the short- and long-term life and use of the product. The initial impression and interaction with the product drive the short-term interest to purchase; the long-term comfort, performance, interaction, and satisfaction are the forces that build brand loyalty. A product’s style, the correct set and location of features, the initial comfort, and confidence in technology are the attributes that customers look for initially. Durability, flexibility, reliability, and service are the features that promote long-term satisfaction and are an expected baseline quality attribute of all products. The Value Opportunities affect both the short- and long-term satisfaction and are critical to brand equity.

The VOA can be applied to the company itself, thereby helping to define the brand. If the brand is considered a product, it must meet the needs, wants, and desires of the company and its customers. What emotional attributes does the customer desire from the company? What is the aesthetic of the company? What are the interactions with the company? What social and environmental impact is expected and desired from the company? What is the differentiation and the company’s personality and context? What are the attributes of its core technology and performance? Finally, what is the quality expectation of its products and services? These questions and the attributes of the VOs provide a basis to define a high user-valued brand identity. As such, we have successfully used the VOA even in this type of application.

An effective product development process ties the corporate mission and brand to the product and customer. All of these activities must resonate with the company’s goals and broader public identity. All of the stakeholders in the company need to be on the same page relative to the product and its relationship to the competition and the rest of the company’s expressed values. But the process is not easy. The team must understand the essence of the user, the desired user experience, and how that understanding translates to product criteria. The company must understand how teams of disciplines that think differently and initially have very different—and often conflicting—goals can work together to create a successful product that meets those criteria. Finally, management and the workforce must understand how all of this integrates into a new product development process with goals, deadlines, and clear objectives. And that is what we turn to in the next chapter.

Summary Points

• Breakthrough brand strategies are tightly coupled with products and services.

• Corporate brand success is linked between corporate mission, program planning, product development, and customer satisfaction.

• Consumers support companies that have personal values compatible with their own.

• Brand within a product is communicated through the Value Opportunities.

• The Value Opportunities applied to the company can help define the company’s brand.

References

1. D. A. Aaker, Building Strong Brands (New York: The Free Press, 1996): p. 68.

2. M. Neumeier, The Brand Gap: How to Bridge the Distance Between Business Strategy and Design (Berkeley: New Riders, 2003).

3. R. M. Kanter, SuperCorp: How Vanguard Companies Create Innovation, Profits, Growth, and Social Good (New York: Crown Business, 2009).

5. Ibid.

6. A. G. Lafley and R. Charan, The Game-Changer: How You Can Drive Revenue and Profit Growth with Innovation (New York: Crown Business, 2008).

7. www.ziba.com/#/work/herbal-essences/