Chapter Six. Integrating Disciplines and Managing Diverse Teams

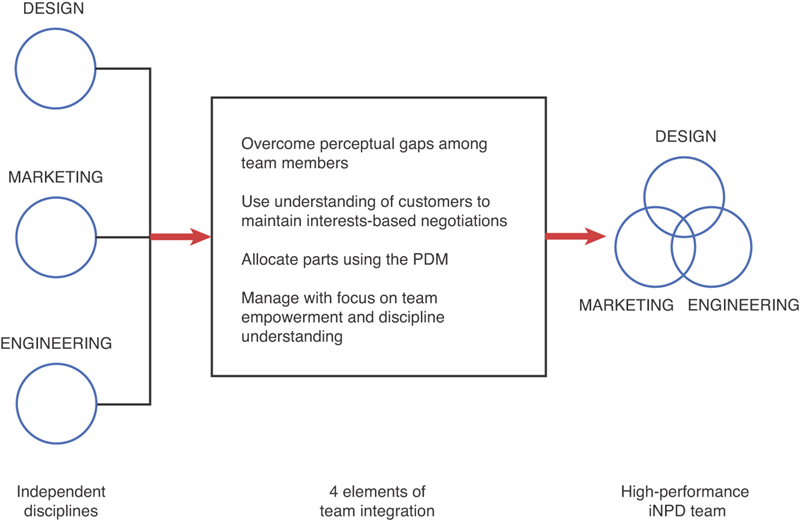

At the core of the product development process are engineers, designers, and market researchers, with each group viewing the product from a distinct perspective. In this chapter, we present research that demonstrates the inherent gap in perception between these different players. Integrated new product development (iNPD) teams must overcome these gaps and seek to become high-performance teams. To do so, the interests of the user must drive effective negotiation strategies between team members. This chapter introduces tools and provides guidelines that will enable you to integrate disciplines and manage diverse teams. The goal of the process, from both the team and management perspectives, is to foster teams that maintain a consistently high overall performance. The process of developing a product should be as rewarding for the team as for the person who uses the actual product.

User-Centered iNPD Facilitates Customer Value

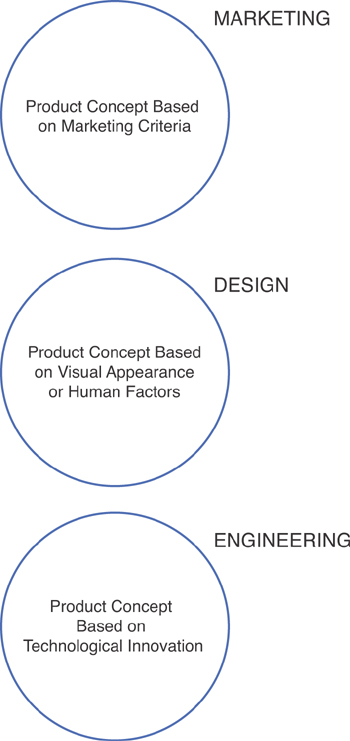

Moving to the Upper Right requires an integrated approach from different disciplines, including design, engineering, and market research. Although each discipline brings knowledge to the process, the team must integrate to create a product that is useful, usable, and desirable to the user. In contrast, the more traditional approach keeps each discipline independent and isolated (as in Figure 6.1). In the traditional model, marketing focuses on product concepts based on marketing criteria: Who wants to buy the product, what will they pay for it, how will it be distributed, and what will it cost to get it to market? Design focuses on product concepts based on the visual appearance or human factors: What should the product look like, how should it be used, and what are the best materials or sequences for the right interaction and look? And engineering focuses on product concepts based on technological innovations: How should the product work, what technology is best, and how should it be manufactured or produced? Marketing traditionally has defined the product, and engineering and design have iterated between themselves based on their respective (and usually differing) interpretations of the marketing criteria.

Figure 6.1. Traditional model of product development—independent disciplines.

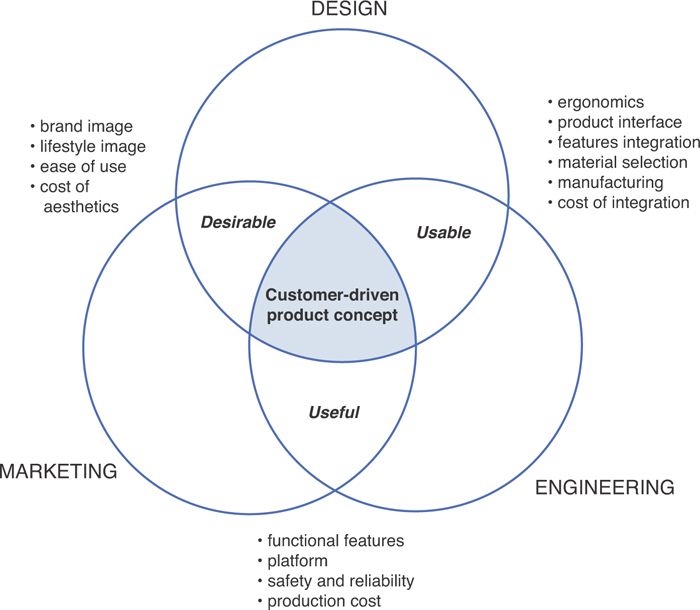

In looking at the commonalities among the three disciplines, design and marketing tend to focus on desirability of a product—the brand and lifestyle images, ease of use, and costs to take into account the aesthetics. Marketing and engineering both focus on usefulness of a product—the functional features, the platform upon which the product is built, safety and reliability issues, and production costs. And design and engineering both focus on usability of a product—the ergonomics, the interface with the product, the integration of the different features and associated costs, the selection of material, and manufacturing. Each overlap is secondarily also concerned with the other two value attributes, but the primary driver of the interaction is as indicated. The point is that the usefulness, usability, and desirability of the product stem directly from the interaction among the disciplines. Thus, the overlaps in disciplines define the value of the product to the customer, the value that leads to success in the market and profit for the company (as in Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Overlap of disciplines leads to value: user-centered iNPD.

Although the need for integration seems obvious, it is not an easy thing to do. People often find that the path of least resistance is the one that is most comfortable, that of falling back on working within their own discipline. When engineers work with engineers, or designers with designers, they speak the same language, think the same way, and use the same tools. If different disciplines have different ways of thinking about and approaching a problem, the overlap of disciplines shown in Figure 6.2 could be difficult. When engineers and designers work together, for example, they often find themselves frustrated, feeling as if the other party could care less about their concerns. These feelings can turn into conflict, which significantly affects the design process.

Managing a group of people from various educational and professional backgrounds is exciting and challenging. Universities and corporations do not teach or even recognize the difference between managing within an area and managing across areas. All of our experience in managing teams and conducting primary and secondary research about teams has given us insights into ways to help optimize interdisciplinary team performance. Teams will perform at their best when individuals are inspired, feel empowered, and gain the respect and trust of the people they are working for. In the current climate of new product development, finding and keeping the talent to build successful teams is a challenge. If people are not treated well, they will leave the company. Product managers must have a range of abilities to effectively manage integrated design teams.

Teams will perform at their best when individuals are inspired, feel empowered, and gain the respect and trust of the people they are working for.

For teams to be empowered, they must:

• Recognize where differences lie and why those differences exist

• Be given tools to work through difficulties in an efficient and productive manner

• Be placed in an environment that supports integrated new product development (iNPD)

This chapter focuses on the integration and management of interdisciplinary teams, first exploring the differences between diverse disciplines in the product development process and then introducing tools and management techniques to help teams overcome those differences and be empowered. The goal is to move from the traditional structure shown in Figure 6.1 to the iNPD structure shown in Figure 6.2. We begin by introducing the concept of perceptual gaps between different disciplines to provide a foundation on which to understand how differently each discipline perceives a product. The discussion is highlighted through our research on product perception among design team members. Next, we characterize high-functioning teams and strategies for conflict negotiation within those teams. All parts of a complex product cannot be designed by all members of the team, so we introduce a new classification system to help teams and managers determine what parts must be designed in an integrated fashion and what parts can be championed by a single discipline. We then provide guidance on how to manage interdisciplinary product development teams, based on our experience with teams in a variety of settings.

Understanding Perceptual Gaps

To understand the root challenges in team integration, we first examine how different these disciplines really are. We worked closely with a major automobile company to explore this issue. One part of the research focused on a qualitative study of studio designers, engineers, and marketing people to elicit their perspectives on the product development process. The study had multiple parts. Here we review one part of the results; we refer to other aspects of the study later in this chapter. For further details of the study, see Cagan, Vogel, and Weingart.1

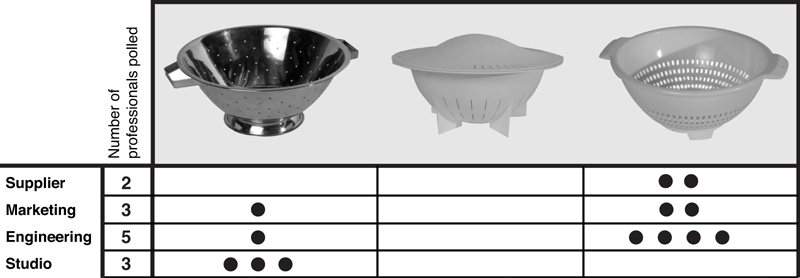

In this part of the study, we chose to focus on a set of colanders, very simple products that are independent of the auto industry. Each of the three colanders shown in Figure 6.3 has its own characteristics. The colander in Figure 6.3(a) is a stainless steel colander; the one in Figure 6.3(b) is a two-piece plastic molded colander from Tupperware that won the 1995 Gold IDSA Excellence Award in Consumer Products (sponsored by IDSA and BusinessWeek); and the one in Figure 6.3(c) is a cheap, one-shot injected, molded colander. To each participant, we asked, “If you owned a company, which colander would you prefer to sell and why?” Participating in this study were three studio designers, three marketers, five engineers, and two suppliers (who happened to be trained as engineers).

Figure 6.3. Three colanders used in study.

The results, shown in Figure 6.4, were significant. All of the designers selected the stainless steel colander. All but one of the engineers, including the suppliers, selected the cheap one-shot plastic colander. And no one chose the award-winning Tupperware colander. The marketers had a mixed view of the products; their contribution to other parts of the study that focused on their industry was more definitive.

Figure 6.4. Overall results of colander study.

It is interesting to note that the one engineer that preferred the stainless steel colander was known for his sensitivity to styling issues and was even identified by the other participants, despite the results being kept anonymous. In following that engineer’s performance in the company, we found he was one of the best at negotiating solutions among suppliers, engineers, and designers. In one instance, he led the effort in developing an innovative solution to a “routine” problem that positively affected many other parts in that subsystem. He was seen as someone able to bridge the impasse in perspectives. His identification clearly indicated that team members are aware that differences in perception typically exist, and that those who overcome them stand out.

When we asked the participants why they had made their preference choice, the designers felt that the metal colander was indicative of qualities such as simplicity, durability, and good value, and was in keeping with current styling trends while saying “Chrome is in!” Chrome had come back in vogue in the auto industry. In contrast, they felt that the one-shot plastic colander was “cheap and ugly looking,” was “not elegant,” and had “an unresolved shape.” The designers, up on current trends, rejected the Tupperware colander as “overstyled,” recognizing that tastes and trends change (what was trendy and award-winning five years previous was no longer the current style).

The engineers had a different view of the products. They found the stainless steel colander an “old-fashioned” aesthetic and “complicated and intricate” due to the multistep manufacturing process, thus directly affecting manufacturing costs and quality control. The plastic one, on the other hand, was affordable (“cheap”) and easy to manufacture. For them, the two-piece Tupperware colander was “confusing,” with the purpose of the top unclear.

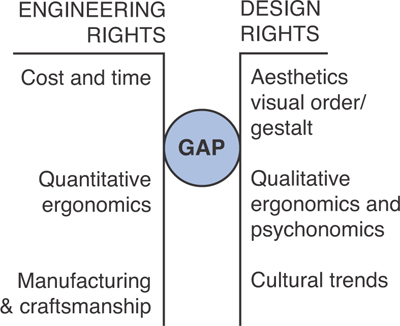

Behind the different preferences between designers and engineers is a more fundamental difference in approach. For the designers, shape and aesthetics drive the decision process; for the engineers, cost and complexity drive the process. These differences in perception are what we call perceptual gaps (see Figure 6.5). Perceptual gaps are the differences in perspectives that team members have that stem from discipline-specific thinking and prevent teams from developing an integrated, interests-based conflict-resolution process. These gaps make negotiation and collaboration strategies difficult.

Figure 6.5. Perceptual gaps model.

Perceptual gaps are the differences in perspectives that team members have that stem from discipline-specific thinking.

Perceptual gaps come from several sources. One stems from differences in education. Engineers are trained to know what is “right.” They use physics and math to model, understand, and eventually control their environment. They recognize what can be done and what can’t be done, based on their understanding of how the world works. They think in terms of function; form is often secondary. They focus on performance, quality, and manufacturing. Designers, on the other hand, are primarily visual thinkers, trained to explore and think about what should be, not what is. They are limited only by their imagination and are influenced by the human side of the world around them. They have a good understanding of manufacturing but are comfortable pushing the limits if doing so allows them to better express their forms. They think of quality as aesthetics and emotional impact.

Another source of perceptual gaps is the inherent personality of an engineer versus a designer. Engineers tend to be black and white—things are right or wrong. They are comfortable with math and use statistics to reach consensus and conclusions. Designers are more comfortable with uncertainty. They view the world around them as evolving and indecisive. Engineers like to get to specifics early, whereas designers like to leave options open late.

We present three particularly relevant examples of perceptual gaps that we witnessed in industrial settings. The first was an interaction between a designer and an engineer discussing a 15 mil gap that occurred between the body of a car and the bumper. Two alternative designs were presented. The designer felt that they had worked hard to achieve a preferred design, if only the engineer would get rid of that gap. The engineer, however, was frustrated because the designer didn’t understand the complexities involved in removing the gap. It wasn’t easy. First, there was the need for structural reinforcement, which would add weight to the vehicle and introduce added complexities to manufacturing. In addition, the manufacturing machines in the intended plant were not capable of producing a part that would meet the designer’s needs. The engineer’s view was “This cannot be done,” but the designer had heard all that before from engineering.

The second example involved an engineering manager who had to work with a design manager who never seemed to meet cost targets. The engineering manager said that the process was similar to bringing a child to a candy store and telling that child to pick out the biggest, best, most impressive basket of candy he could. The child would get very excited and really work hard to pick out the best candy he could. Then when he came up to the register, his parent would say, “Wow, that’s great, but you have $200 worth of candy and we have only $20, so you will have to put most of it back.” The engineering manager saw himself as the parent and the design manager as the child. No one wants to tell a child that he can’t have what he wants, but the fact is, the money is limited. The parent will work with that child to make sure the child gets the things he really wants. But the parent sees the child kicking and screaming and getting upset, which does no good because the child still will not be able to get all that he wants. He understands that it’s hard to put that candy back. But if the child had let the parent walk around through the store calculating the sum from the beginning, this hurtful scene at the cash register would never have happened. But the child (designer) does not want him to do that.

The designer’s view is quite different. The third example came from a design manager discussing his interactions with engineers. To him, the form of a product was like a bowl of gourmet soup. All the ingredients are there for a reason—it tastes good! Although you can take the pepper out or reduce the amount of salt, doing so sacrifices the taste. But you can’t really say why. If you keep going, you end up with a bowl of water. Designers are like chefs; they understand how everything fits together into a great-tasting soup (or product). The engineers keep trying to cut costs by taking out a little of this and a little of that until the soup (product) tastes (looks) bland.

Differences in perception are an important and positive part of the design process. These differences help provide the trade-offs that make products innovative and yet affordable, and produced on time. However, these gaps might also disrupt the process if the players do not respect each other (as with the second and third examples). Each player must appreciate the alternative perspectives (lacking in the first example). All too often, disciplines feel superior, leading to roadblocks in the design process and preventing group consensus. At times, this leads to personal conflict with lasting effect. Often different players work together repeatedly, but if early encounters are negative, developing trust and respect in future projects will be hard.

Team Functionality

Individuals from diverse disciplines face perceptual gaps when they come together to work as a team. In addition, teams must navigate their own diverse personalities. We turn now to the literature and our own experiences with team functionality, especially in the design process. We examine the aspects of collaboration, negotiation, and performance.

Team Collaboration

Conflict within a team does arise, and it must be managed. Weingart and Jehn2 argue that collaboration is the key to managing that conflict. The first step is to identify whether the intrateam conflict is based on the task at hand (task disagreements) or personality-related issues such as political views, social activities, hobbies, and opinions about clothing or hairstyles (these types of conflict are called nontask conflict). Our view is that task conflict can often be beneficial to the design process. The goal of iNPD is not to remove conflict, but to make it productive and focused on the task at hand. Nontask conflict tends to be detrimental to the team as a whole, interfering with the project, taking valuable time away from the effort, and at times exacerbating personality differences that prevent team members from communicating at all. The goal is to minimize nontask conflict and manage it outside the project environment. When teams are formed, we recommend that they take time outside their work environment to get to know each other through a social activity. For example, one of the most highly functional teams we have observed went spelunking. It is also important to realize that team members don’t need to like each other. Instead, they need to respect each other professionally and focus on the task to get the job done. We observed one team whose members clearly didn’t want to be in the same room together. By focusing on the project and using our user-centered iNPD method, they were able to produce a fantastic design. Of course, the preferred state is for team members to work out their nontask disagreements and enjoy the process.

When the focus is on disagreements about the task at hand, collaboration can take place. Through collaboration, disagreements can be altered into joint gain. The idea behind collaboration is not to compromise; compromise means that each party in the process “gave in” and left the process disappointed. Instead, collaboration implies more mutually beneficial results based on more effective communication. Weingart and Jehn describe three techniques to support collaboration.

The first is to create a group atmosphere that supports team focus, the capability to solve the problem, trust among each other, and open communication channels with which to discuss conflict. In many ways, we see trust as the most critical. Trust is hard to build and easily broken down. Trust must evolve slowly through positive interactions and responses. Trust might be slow to build, but we have seen high levels of trust lead to very efficient and productive design processes.

The second technique to support collaboration revolves around group member behavior. The goal is to look for and act on opportunities for joint gain, situations in which both parties can win. It is critical that team members exchange truthful information. Factual information keeps team members aware of each other’s needs and helps substantiate each person’s position. Similarly, exchanging information about one’s priorities can facilitate trade-offs across different issues. If some issues are more important to one party than another, making concessions on the less important issues might enable each party to gain on other, more important ones. In addition, this increases insight into the other party’s viewpoints, which can make future collaborations more efficient. Once a conflict takes on a personal or competitive tone, it is very hard to disperse. Instead, people tend to “one up” each other, and the conflict gets worse and more personal. The key to success is to recognize that this is happening and try to respond with a new tact, a direct response that brings the conflict into the open, or a more integrative and collaborative response that might shift the process back on track.

The third technique to support collaboration focuses on the mindset of the team members. Many people approach resolving conflict as a win–lose situation and think that one party has to win while the other comes out on the short end. Of course, this does not have to be the situation. Instead, an attitude of cooperation and collaboration and an openness to creative thinking can often lead to win–win situations. We have observed both types of attitudes, and the win–win view usually leads to innovative, superior solutions. Finally, collaboration requires interdependence on other team members. Negative emotional outbursts and attitudes such as frustration and anger tend to interfere with collaboration. These emotions need to be kept in check and resolved as nontask conflict outside the scope of the project.

Negotiation in the Design Process

Now that strategies and techniques are in place to set up collaborative efforts, the team needs to focus on approaches for negotiating solutions to conflicts that emerge in the design process. We turn to a discussion on the use of interests, rights, and power, as discussed in Ury, Brett, and Goldberg,3 and our investigation into their use and effectiveness in the design process done in collaboration with Professor Laurie Weingart at Carnegie Mellon’s Tepper School of Business.4 As people choose to use interests, rights, or power, they significantly affect the tone, atmosphere, and effectiveness of the negotiation in design.

Interests-based negotiation addresses all of the concerns, desires, and needs of each player in conflict. People’s preferences and priorities can be learned and trade-offs can be found to overcome barriers so that everyone wins. This implies that people exchange information, that all relevant stakeholders are included, and, in particular, that interests of the user are considered. The result can be innovative solutions to difficult problems. This is the ideal approach to conflict negotiation in the design process.

A rights-based approach uses standards, precedence, and views of what is right and wrong to resolve a conflict. Here there is either a winner or a loser, or compromises must be made, indicating that a better solution probably was available. Often prior solutions, industry averages, and traditional profit or cost targets and analyses are the basis for such negotiation. Although rights have their place in the design process (as discussed later in this chapter), solutions based on precedence alone are often routine or mundane and can be ineffective.

Finally, a power-based approach is one in which a person is forced to do something he wouldn’t otherwise do. The result is that people feel bad about each other, and the losing party often enters future engagements looking for revenge. Power-based techniques include strong-arming, threatening, invoking the boss’ power, and hoarding information.

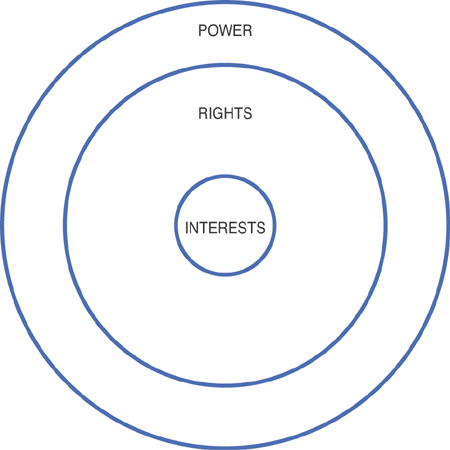

Figure 6.6 shows three concentric circles, with interests in the center, rights in the middle ring, and power on the outside.3 As shown in the figure, interests-based negotiation might be the central goal, but such negotiation is realized only by understanding that one or more parties could retract to rights or even power if the process doesn’t have complete buy-in from all parties.

Figure 6.6. Interests, rights, and power.

(Based on Ury, Brett, and Goldberg3)

This is particularly relevant with full-service suppliers who participate in the design of a system or part. Although all players should express their interests and be aware of the interests of others, fundamentally, the company that hired the supplier could very well fall back on the position of threatening to look for another supplier. Also, this is relevant within a team when one person is more highly ranked than the others. Although the middle or upper manager could easily unilaterally make a decision, doing so would undermine the cohesiveness and attitude of the team. Participants might think, “Why should I bust my butt to save money or improve the quality or aesthetics of a part if the manager is just going to throw away my effort?”

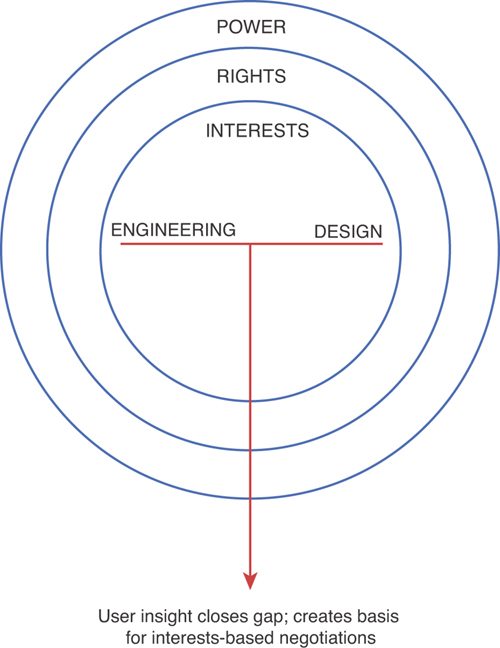

Figure 6.7 maps the concentric interests, rights, and power circles of Figure 6.6 onto the perceptual gaps model of Figure 6.5. The common situation is that there is no basis for interests, often thanks to perceptual gaps. Instead, team members rely on rights to argue for their perspective. In the end, upper management decrees a decision from above. Clearly, for an effective iNPD process, team members must overcome these gaps and use an interests-based approach to negotiation. To maintain an interests-based stance is to recognize the long-term gain from a cohesive, collaborative team. By driving the process based on the user’s interests (the needs, wants, and desires of the customer), the process remains focused, and all team members can bridge their perceptual gaps by focusing on a common argument of why decisions are chosen (as shown in Figure 6.8).

Figure 6.7. Typical perceptual gaps and the dysfunctional use of interests, rights, and power.

Figure 6.8. iNPD perceptual gaps negotiation model—the user’s interests help bridge the gaps.

When teams use the collaborative techniques discussed in the previous section in conjunction with interest-based negotiation, we have seen the design process become more effective, less emotional, and more successful overall. We turn now to an understanding of what is considered a high-performing product development team.

Team Performance

The goal, according to Katzenbach and Smith in The Wisdom of Teams,5 is to develop and manage high-performance teams. High-performance teams have these characteristics:

• Are self-motivated, accept criticism, quickly establish an atmosphere of mutual respect, and integrate different perspectives

• Function horizontally instead of in a hierarchy, and shift leadership roles as appropriate

• Actively seek advice and input from managers, expert advisers, and potential customers

• Want to identify and correct flaws rather than become overly defensive

• Have a clear rationale for their decisions

• Tend to have a sense of humor as a group and use it to shed stress

• Quickly become experts in the subjects needed to develop insights into the product opportunity

• Accept the fact that they are mutually responsible for the work of the team

• Develop the Gestalt dynamic, in which the team is greater than the sum of the individual capabilities of its members

The ideas expressed by Covey6 and Kao7 are consistent with these points. Covey points to looking for win–win decisions and stresses learning to master the art of hearing and being heard. Perhaps the most important aspect of Covey’s principle is the shift from being independent to understanding the value of interdependence. Most of us are taught that independence is the goal to shoot for, but Covey considers this only the beginning. Realizing that your success is inextricably linked to the input of other team members makes you able to get the most out of a team experience. Kao compares successful teams to a performance of improvisational jazz. When musicians are “jamming,” all the players know where they are going without requiring a clear vision of the end, and they respond and play off one another, building as they go. No one is reading sheet music, and they are not playing from memory. Applying this approach to product development requires trust and listening and is based on the belief that the best results will unfold naturally as work progresses. True innovation is not developed from preconceived notions. Innovation is developed as a result of the maturing of the wisdom of the team to see the direction and move with it.

An ideal high-performing team evolves quickly and, therefore, makes the most of each phase of the program. If teams take time to mature, they do so at the expense of the process. If a team is not functioning effectively early, it might fail to identify a true opportunity. Team members’ research of the opportunity might not be as deep, preventing them from identifying true insight that leads to Value Opportunities. As Covey points out, if team members have achieved the level of self-confident independence, they are more able to adapt to the challenges required to work in an interdependent team atmosphere. Teams that have members who lack the first level of Covey’s personal development often need to learn to trust and share ideas.

The challenge for managers is to get teams to a high performance level as quickly as possible. A manager must expend the most energy early in the process, to get the team up to speed, and must stay with the team until it shifts into high-performance mode. When that state is achieved, the manager can spend less time questioning the team’s insights and decisions. The role of managing then shifts to supplying the team with resources, clearing obstacles for the team, and serving as a check on the process.

In the book Flow, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi8 contends that individuals (and we believe teams as well) work best when challenge and ability are both set at the proper level to achieve maximum performance and satisfaction—namely, a “state of Flow.” When teams achieve this state, their dynamics are positive, team focus is heightened, and they are able to shut out distractions. High-performance teams achieve a state of Flow more naturally. Managers have to work harder to help lesser-functioning teams reach the state. Several advantages emerge while helping teams achieve a state of Flow:

1. The positive atmosphere increases the potential of creating breakthrough products.

2. Team members enjoy the process and gain satisfaction from seeing the end product.

3. Positive team performance extends to future experiences within the company.

P&G has developed an interesting model for supporting the team. Clay Street is the name of a street in the old part of downtown Cincinnati known as Over the Rhine. Clay Street is also the name given to the innovation workshop developed during Claudia Kotchka’s tenure as vice president of design under A. G. Lafley. Clay Street began when Kotchka brought in David Kuehler, who had developed an innovation workshop based on the entertainment industry at Mattel. This is a variation on what companies historically called a “skunkworks.” However, the structure of this version of the offsite is very different. The approach uses a theater structure, with the team leaders working in the role of director and assistant directors. A cross-section of a business unit is chosen to come to Clay Street for eight weeks. The team members must completely disconnect from their regular role in P&G. The process allows everyone to reinvent themselves in a new role as performers in the play. The eight weeks end with a performance and story, not as a formal PowerPoint presentation, as is so prevalent in business. Through a variety of exercises and experiences, teams learn to see the opportunity they are charged to work on in new ways. They learn that innovation can come from anyone. They also have inspirational speakers come in for sessions, and they take field trips for ethnographic research and inspiration. It was in Clay Street that a team defined the brand for Herbal Essences, discussed in Chapter 4, “The Core of a Successful Brand Strategy: Breakthrough Products and Services.”

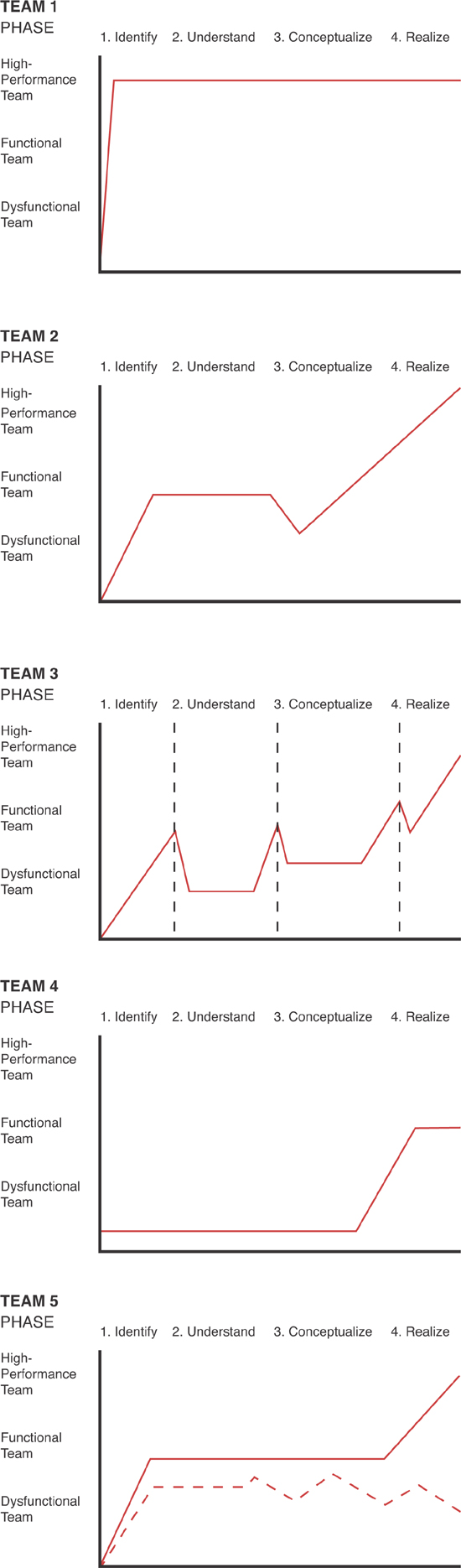

We have observed a variety of teams in our work. We have learned that teams can evolve quickly in a managerial atmosphere where the communication is clear, consistent, and constant, with a structure that helps support the team’s development. A team can lose direction, and if left undiagnosed for any length of time, reversing the trend can be difficult. As we have fine-tuned our approach, we have been able to get teams up and running quickly in the first phase. Figure 6.9 illustrates five team profiles over the product development cycle. Team 1 is the ideal team, able to quickly move to a high-performing team and produce a truly successful product concept. Team 2 is somewhat typical, in that it gradually becomes functional and then high-performing, with possible ups and down as its members gain trust in each other and the process. Teams 3 and 4 are examples of how teams should not function. Team 3 is barely a functional team, achieving success at design reviews only at the end of each phase. Team 4 is every manager’s nightmare. The team does not follow the iNPD process and, due to personality conflicts within the team and inappropriate discipline participation, never functions well and produces, at best, a mediocre product. Management must restructure the team to allow the members to achieve at least a functional level of performance. Finally, Team 5 is an interesting dichotomy. The team members do not like each other and have strong personality conflicts—the dotted line shows the team performance based on personality only. But unlike Team 4, they follow the iNPD process and are able to produce a high-quality product as a functional team and, at the end, even achieve high-performance status, as illustrated by the solid line. This last team shows that, even if the team members don’t like each other, if they respect each other’s abilities and follow the process outlined in this book, they can still produce a high-quality and highly valued product.

Figure 6.9. Five team performance profiles across the product development cycle. Team 1: High-performance team from beginning to end; Team 2: Early dysfunction evolving into high performance; Team 3: Team peaked for Phase reviews, decreases in function in between reviews, and fails to maximize process; Team 4: Dysfunctional throughout, and management needs to restructure it to achieve a functional team level; Team 5: Team performance is functional and team dynamics are up and down, but the team respects the process and works through to a high-performance result.

Part Differentiation Matrix

Not all parts of a product should be designed the same. That might seem obvious, but it isn’t to most companies. Companies tend to think about a system and its components in the same way. We have found in our collaborations with industry that two characteristics most affect how parts should be designed.

The first is the lifestyle impact, those parts that capture the essence of the fantasy of the product to the customer and make the product desirable, especially at point of sale. Any parts that a customer sees or touches have primary lifestyle impact. These parts have the biggest effect on the product brand. Any parts that affect the performance of the product but are not visible and tend to merely satisfy a level of expectation of the user have secondary lifestyle impact. These secondary lifestyle impact parts do affect satisfaction, especially over the long term, but they aren’t critical to the semantics of the product and its statement about who the user is.

The other characteristic is the complexity of the part or system. By complexity, we mean the inherent coupling of features within the part and its interdependence with or impact on other parts of the product. In other words, how connected is a part to other parts, by both physical connectivity and functional connectivity?

These two characteristics can be mapped against each other in a two-dimensional matrix, shown in Figure 6.10, which we call the Part Differentiation Matrix (PDM). In the PDM, the top cells represent primary lifestyle impact components; the bottom cells represent components of secondary lifestyle impact. Complexity is represented through the horizontal axis, with high complexity to the right and low complexity to the left.

Figure 6.10. Part Differentiation Matrix.

For more complex products of multiple systems and subsystems, a company clearly would not have the resources for complete, integrated teams to design every part, down to the nuts and bolts. Such an approach, although theoretically ideal, is not feasible in practice. The PDM lends insights into just how integrated a team should be to design a given part and what negotiation strategies are most effective for an efficient design process.

The lower left cell of the PDM represents commodity or incidental parts, namely parts that are not highly interdependent or complex and that have little influence on brand or point of purchase sale. These are parts that the customer doesn’t see and doesn’t generally care about. Numerous suppliers manufacture these parts, and as long as they meet some minimum quality standard, it doesn’t matter who makes them. Integrated discipline design is not necessary except for the specification of the part. Cost is the only factor that would influence the selection of one manufacturer over another. The minimum quality standard cannot, however, be taken for granted, for customers will blame failure of these parts on the manufacturer of the product, not the component.

On the other hand, in the lower right cell, that of high complexity but secondary lifestyle impact, are parts that won’t directly influence the purchase of the product but will influence the reputation of the product and the likelihood that a customer will return to buy another of your products. This is the platform and core technology of a product. These are the parts that most influence long-term customer satisfaction, based on the quality of the product’s engineering. The influence of these parts on sales is subtle. The customer has a basic level of expectation about performance of these parts at point of purchase, but as long as that expectation is met, the parts will not influence sales. Often company reputation is the most critical part of satisfying customer concerns for these parts. Here engineering takes the lead in part development. The design group, however, must still buy in on the design. The details of the platform and system integration have important implications on how parts with primary lifestyle impact can be designed. For example, attachment points, overall size, and potential weight limitations are all determined or at least influenced by the design of these lower-cell parts. So although it would appear that the engineers alone should design these parts, it becomes clear that some level of team integration is needed. Within services, these are the technology components that support the service and make it function, but the user doesn’t see them.

The upper left cell, those parts of low complexity but primary lifestyle impact, has a similar interaction between disciplines. These parts are primarily driven by visual aesthetics and have minimal function. Instead, they are critical in their support of the brand identity of the product. These components help sell the product and are the most visible aspects of the product at the point of purchase. They are part of the soup referred to earlier: You aren’t sure why they belong, but if the design works, then every one of them has a purpose. Here design takes the lead, yet engineering must deliver the part at a sufficient cost and quality. As with the lower right cell, development of the parts in the upper left cell also requires some level of team integration.

The upper right cell, that of primary lifestyle impact and high complexity, represents parts that merge features and resulting technology with style and resulting brand image. These parts are critical to the look and feel of the product, its performance, and the effect the product has on the customer that leads to a sale. These parts (usually subsystems) require strong input from all players in the development process. In particular, design and engineering must work together in an integrated fashion to create part systems that meet identity, technology, and feature requirements. User buy-in to the product depends on the success of this process, and, of course, a user focus is required for the process to succeed.

The PDM was developed through our research in the auto industry in collaboration with Professor Weingart.1 As shown in the sidebar, the matrix is quite effective in focusing integrated effort and resource allocation in the vehicle development process. What we learned from the auto industry clearly transfers to any product that holds a reasonable level of complexity, requires user interaction, depends on styling and identity, and utilizes sophisticated technology. What is interesting is that the PDM can also lend insight in simple, straightforward ways to all manufactured products. Furthermore, the PDM supports the infrastructure of service industries. We now examine its application to the FIT System, the Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker, and the support products for Starbucks.

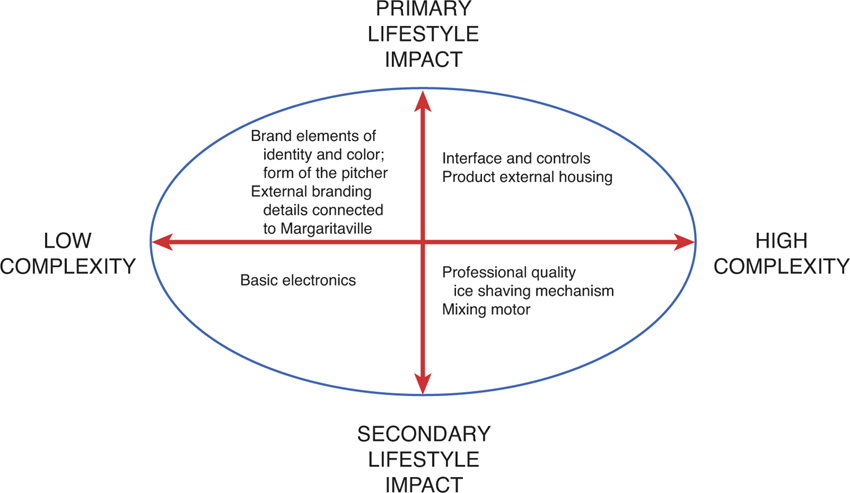

First, consider the PDM for the Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker (see Figure 6.11). The upper right cell holds the key integration that delivers the user experience. This includes the interface and controls, as well as the overall form of the housing. The lower right cell includes the technology to shave and blend the ice, the development primarily the task of the engineers. The branding elements that connect the product to the Margaritaville brand were the primary responsibility of the industrial designers, as indicated in the upper left cell. This also included color and form details of the product, and elements such as the design of the pitcher to look different than an ordinary blender container. Very little exists in the lower left cell, which includes the commodity component parts and secondary components such as the more basic electronics; the team paid attention to every detail of this product in terms of its style, technology, and integration.

Figure 6.11. Part Differentiation Matrix for Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker.

The BodyMedia FIT System, an advanced, high-tech product that integrates into people’s lifestyle while trading off complexity, makes the PDM relevant for the product’s compliance and success (as shown in Figure 6.12). Here the upper right cell contains the housing and strap, but also the Web interface—these are the interfaces between the technology and the user. The technology itself is the majority of the parts of the FIT and is represented in the lower right cell, which includes the sensors and information communications technology. The lower left cell includes the individual electronic components and batteries. The upper left cell houses the logo and external panel for the product. This is very much a product designed through integration. Although the designers captured many features in the shape and style of the housing, they had to work closely with engineering to guarantee that the technology would integrate into the form.

Figure 6.12. Part Differentiation Matrix for BodyMedia FIT System.

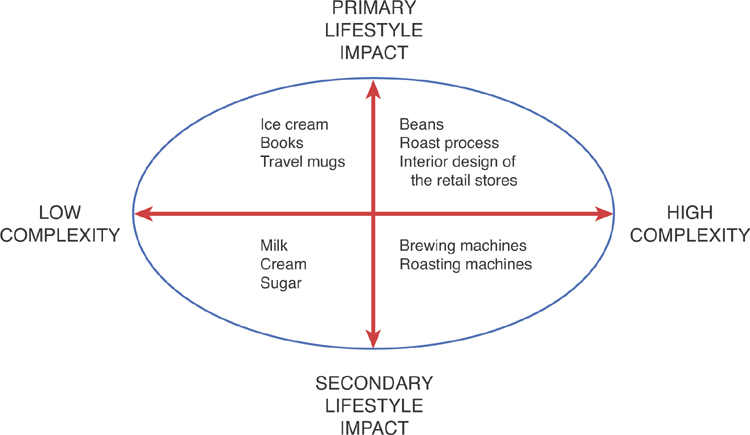

Starbucks, a service product, also can benefit from the PDM (as shown in Figure 6.13). Here the PDM decomposes all aspects of the support structure for the service environment and product line for Starbucks, from the perspective of style and complexity/technology. The core players are not necessarily traditional product designers or engineers. The personnel at Starbucks fulfilled the roles of engineering, design, marketing, planning, and finance. In many ways, this case study shows that discipline background is not critical. Instead, what is needed is the ability to fulfill the multiple roles required to create a product or service in the Upper Right of the Positioning Map. The upper right cell of the PDM (as opposed to the Positioning Map) is the core product—the beans, roast process, and interior design of the retail stores. These cores are the focus of the designers, the engineers, and the marketing and planning group. The lower right cell is the core machinery—the coffee brewing and roasting machines that are standard for the industry. The lower left cell houses the extras, such as milk, sugar, and napkins. In the upper left cell are the peripheral products, including ice cream, books, and travel mugs. The peripheral products are designed by the designers and farmed out for production. The roasting and brewing machinery is specified by Starbucks and supplied by vendors. As Starbucks has grown and diversified, it has continued to maintain its core standards—that is, Starbucks coffee consistently uses top-quality beans, roasted with precision, with coffee served in a warm, inviting environment. The recognition of this core product in the upper right cell of the PDM keeps the company focused on its strength even through its rapid growth.

Figure 6.13. Part Differentiation Matrix for Starbucks.

In the ideal world, all parts of the design would be developed in an integrated fashion, but time and financial resources limit the feasibility of such an idyllic process.

The PDM helps the product development team understand how to allocate resources between focused, discipline-driven design and integrated part development. Again, in the ideal world, all parts of the design would be developed in an integrated fashion, but time and financial resources limit the feasibility of such an idyllic process. The PDM, however, does not imply that engineers alone should design parts in the lower right cell while designers focus on the upper left. Not only do engineers have to produce the parts the designers create, and the designers have to build on the platforms subject to constraints imposed by engineers, but the basic axiom of iNPD is that all members of the process are part of an integrated team. As such, each team member brings perspectives and expertise to the process that must be welcomed and appreciated. Thus, all team members should be encouraged to comment on the design of all parts and verify their integration into the overall functionality and theme of the product. Part design cannot take place in a vacuum.

As a last comment on the PDM, note that the lower cells tend to be more science driven, with more predictable costs. The upper cells, however, are more emotionally driven and have less predictable costs. Many companies try to set cost targets up front on all parts of the product. Although this is a reasonable goal, it must be realized that, until the lifestyle issues of the product are understood and integrated into the design, predictions for costs of upper-cell parts are just estimates; flexibility is required. Cost- and lifestyle-driven processes must work in balance; there is a limit to how much a consumer will or can pay for a product. The goal is to add the right features for the appropriate cost; the PDM tells us which features directly affect sales and can support added costs. Using the typical cost-driven approach for the design of all parts often causes team conflict—and rightly so, as discussed in the next section.

Team Conflict and the PDM

By examining the PDM in the context of perceptual gaps, it should seem obvious that unproductive conflict is inevitable without a proper iNPD method. Conflict in the upper left (primary lifestyle impact and low complexity) and lower right (secondary lifestyle impact and high complexity) cells occurs because one group needs to take the lead, but the other still must influence the part design. In the upper right cell (primary lifestyle impact and high complexity), conflict emerges because each party fights for its own perspective within a challenging design framework. Recall earlier in this chapter that we engaged in a study on perceptual gaps among product development practitioners in the auto industry. In a different part of that study, we focused on perceptual gaps in the primary lifestyle impact (upper) cells of the PDM. We found stark contrast in the types of gaps and conflicts that emerged from these two cells.

The auto industry, like other industries, is challenged by constant time-to-market pressures; the conceptualization, detailing, and integration of a large number of parts; limited space; limited budget; and a variety of government regulations. As studio designers complete part designs, engineers must determine their cost to manufacture and begin the design of molds, usually in conjunction with a supplier. The more parts that can be completed early, the less pressure there is toward the end to get every part finalized and integrated. To the engineers, the parts in the upper left cell of the PDM are relatively simple parts that should be completed early in the design process. To the studio designers, these parts should certainly be envisioned early in the process, but there is no way that a part can be specified until much later in the process because it must fit within and help express the brand identity of the vehicle. Engineers do not want to consider the cost of brand identity, but, as discussed earlier, designers do not tend to consider the complexities in manufacturing of even such simple parts. Thus, the upper left cell parts (exterior side molding, in our study) can cause conflict because of a difference in perspective of when a part can be designed and how complicated the part should be.

Parts in the upper right cell introduce different challenges and conflicts into the process. By examining a primary lifestyle impact and highly complex system (that of the design of the door system), it became clear that all participants understood the difficulty and complexity of the design task. Challenges included goal conflicts (between disciplines and trade-offs among design requirements), styling, human factors, component packaging (whenever a component is moved, it affects the placement of many other components around it, much like the placement of pieces in a jigsaw puzzle—except that here there is no clear “correct” answer), and craftsmanship, or fit and finish. When participants (engineers and studio designers, in particular) were asked about the primary challenge in designing the system, however, each discipline said that its own was the biggest challenge. In other words, each discipline fell back on its own world as the driver of the process. Thus, upper right cell parts of the PDM are challenged by the sheer complexity of the process and the need for each individual to get his or her own job done.

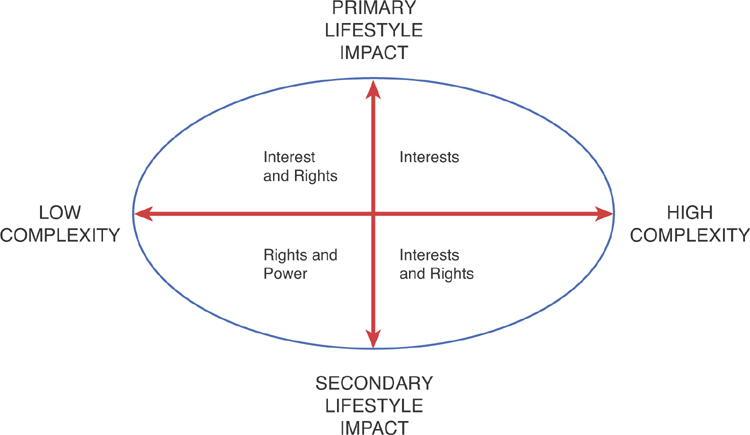

It is interesting to see how our discussion of interests, rights, and power applies to the PDM.2 As shown in Figure 6.15, the upper right cell requires the use of interests—and only interests in solution negotiation. It is critical that the interests of each discipline be taken into account. Further, because this team will likely work together for a reasonably long period of time, any other approach will cause distrust and long-term problems for the team’s dynamics. The cross-diagonal cells of the upper left and lower right also should be mostly based on interests, but here rights also come into play. Because one discipline takes the lead in these cells, their previous approaches or standards for designing the part become more prevalent. In the lower left cell, interests are not needed. Instead, rights and power can be used to get the best price and delivery time for the commodity parts.

Figure 6.15. Part Differentiation Matrix and the application of interests, rights, and power.

PDM and the Role of Core Disciplines

It follows, then, that there must be balance between team integration and discipline-specific activity. The goal of iNPD is not to neutralize individual discipline expertise, but for each individual to bring to the table the strength of his or her knowledge. Engineers are the only group trained to perform analytical simulation such as finite element or computational fluid dynamics analysis. Engineers tend to be the people trained in the details of manufacturing. Designers tend to be the players trained in human factors (at least through a qualitative sense), aesthetics, and 3D physical modeling. Marketing and finance tend to be trained in cost structure and market characterization.

Engineers and designers can bring a unique perspective to market research, designers and marketing researchers to feature definition, and engineering and marketing researchers to user preferences. However, each discipline still is responsible for details in their area. Thus, it is important in companies where teams colocate and integrate that individuals maintain their training in their fundamental area. Furthermore, each individual is best suited to understand advances in his or her area in other programs in the company. Thus, you are advised to encourage individuals in a discipline to interact in some formal or informal setting with people of the same discipline from other areas of the company. This could take place, for example, through seminars where people present discipline-specific details of their team’s product.

The goal of integrated development is not for individual discipline expertise to become vanilla, but rather for each individual to bring to the table the strength of his or her knowledge.

Issues in Team Management: Team Empowerment

Integrated design teams are difficult to manage. Many managers feel that they are supposed to be the expert and have all of the answers. Some even think that they are supposed to make all of the design decisions. Typically, this just does not work. Companies need interdisciplinary teams because no one individual has all the answers. Companies make the effort to hire the best people into those teams because they believe in their employees’ talent. The best approach to managing an integrated team is to give the team direction and stay back, taking on the role of advisor rather than micromanager. In many ways, the manager is like a coach, guiding and training the team; however, the team must win the game. Like the coach, the manager is typically not in the trenches, observing and understanding firsthand the needs, wants, and desires of the user. The team members are, and they must produce the product that succeeds in the marketplace.

The manager faces two main challenges:

1. How to foster creative problem solving within limitations of time and economics

2. How to manage the team’s particular needs at any given point in the process, keeping in mind the broader issues and goals of the entire program

This section describes approaches and insights to meet those challenges and manage interdisciplinary design teams. We have gained these insights through management of and discussions with a variety of teams in a broad base of settings. Although this team empowerment approach might be difficult at first, most participants tend to step up to the plate and excel in the product development process.

Understand the Corporate Mission

Recall in Chapter 4 the four levels of corporate commitment to product and brand: corporate mission, program planning, product development, and customer satisfaction. It is the program manager’s job to translate the corporate mission into a successful product in the marketplace. A program can get lost in detail and small problems, and start to move away from both the customer focus and the strategic plan. It is the manager’s responsibility to make sure that the team understands and stays true to the corporate mission, and to understand the impact of brand strategy on the process. As the team develops new insights into customer trends, the program manager is the conduit to feed that information back to upper management.

Serve As a Catalyst and a Filter

The manager needs to maintain a balanced view as neither a “company man” with a top-down approach nor an overprotective manager with a bottom-up focus. Supporting top-down management can be an effective way to gain advancement in a company. Making sure you are always doing what your superiors say and then telling those under you what the rules are is a safe way to manage. However, this approach often stifles a team and limits innovative solutions. Becoming overly defensive and protective of a team is another style that is used. This “champion of the little people” approach makes you a hero with your team. However, it also creates negative relationships with upper management and isolates the team. This second approach is far less effective for achieving advancement than the first method. Maintaining a balanced point of view is important. Teams are often right and insightful. The program should create possibilities and new ideas that management mediates and, at times, allows to alter preprogram strategies. Knowing when to push upper management for more time resources or a shift in focus is more art than science. However, successful managers trust their teams and must be able to separate the normal tendency of a team to want to do things a different way from its true insights and breakthroughs.

Significant product breakthroughs usually have a cost attached to them. The original cost targets might be challenged when a breakthrough idea emerges. The program director must make a decision to argue for increased cost or to tell the team to make it work in the program cost structure. This is a matter of understanding the dynamic tension between constraints and variables. Every program has areas where change and experimentation are required (variables) and other areas where rules must be adhered to (constraints). For instance, if a product must debut at a trade show in 12 months, that constraint cannot be ignored. Missing an external deadline could throw off a program by an entire year. Finalizing the aesthetic features prior to understanding the lifestyle desires of the customer, however, is a variable that must never be prematurely frozen. Doing so will lead to failure of the product at the show or in the marketplace. Making sure that constraints are respected and variables are sufficiently investigated is a talent that a good manager must cultivate. The program manager needs to work with upper management to set the product development schedule, such as determining appropriate deadlines for completing the four phases. Doing so ensures that the team has time to explore the variables and meet the constraints.

In balancing the interaction between upper management and the team, the manager must shield the team from distractions, providing an environment that promotes focused work on the project at hand. Distractions with constant peripheral meetings break the concentration of the team members. Furthermore, the team manager must prevent upper management from interfering with the iNPD process, especially when upper management does not understand the issues. Dave Smith, a consultant for Crown Equipment Corporation, set up a skunkworks away from the corporate setting to promote integration in the team during the development of the Wave. One way to shield the team from distractions is to prevent those distractions from the start. Problems in terms of time pressure, budget cuts and restrictions, and personnel cuts, as well as other unanticipated problems that arise outside the focus on the product, should be the responsibility of the manager. Let the team members focus on the project at hand.

Be Unbiased

Most managers have a core discipline that they consider theirs. When managing an integrated team, having a discipline bias can be threatening to team performance. Very often a discipline-specific focus can lead to a perception that the manager’s domain is considered superior to other fields. iNPD managers must learn to see the program through the eyes of different disciplines. They must learn to respect the commitment and value that an integrated team has. One way to resolve this is to create management teams from key disciplines. This might not seem cost effective, in that extra personnel are required, but it can be a very successful model in the long run.

Although team members will collaborate with each other across disciplines, they must bring their own discipline knowledge to the process. Integration means joining together different knowledge, ideas, and approaches. Managers must be sensitive to the wisdom of disciplines through team members, allowing each perspective a voice appropriate for the discussion or problem of focus. The Part Differentiation Matrix, mentioned earlier, can help a manager frame the approaches to different aspects of the product.

Empower and Support the Team

It is appropriate to make the analogy that managing an iNPD team is similar to other creative fields in sports and entertainment, such as a coach, orchestra conductor, and movie director and producer. Two main approaches to management exist: dictatorial and benevolent. In sports, managers’ and coaches’ approaches to their respective sports are out there for everyone to see. Coaches who win consistently have found a way to blend their knowledge of the game with their ability to mold talented individuals into an integrated team. Any good team must have diverse types to fit different roles. A variety of coaching styles range from dictatorial and totally controlling to benevolent and supportive. Here are some versions that we think fit leading iNPD teams.

John Wooden is perhaps the quintessential coach of all times and his Pyramid of Success9 describes how to be a winner as a person, not just a player. Phil Jackson as a modern model of coaching could take diverse and sometimes difficult personalities and get them to blend together. He used a style that educated players to work as a team and around the triangle offensive model. He had great talent in Michael Jordan, Shaquille O’Neal, and Kobe Bryant, but he also always complemented that with spot players who had key abilities and limited roles, particularly three-point shooters. Mike Krzyzewski, known as Coach K, recently passed his mentor, Bobby Knight, as the winningest coach in college basketball. Knight had an intimidating style of coaching that was seen as excessive; it eventually led to his dismissal from Indiana University. Coach K has blended Knight’s approach with a softer style at Duke. All good coaches seem to find an opportunity gap in the way to mold players and win. They then build a coaching staff to implement it and draft players that fit the scheme. They also understand the competition and leverage their weaknesses. Coach K knows that, in the last two minutes of a half, teams tend to let up, so Duke players work harder in that time period. John Calipari built a team of primarily freshmen at Kentucky and won the NCAA Basketball Championship. He read the SET Factors of college basketball, where today talented players often leave after one year. He took a disadvantage and made it an advantage by drafting players whom he knew he would have for only a year, but he gambled that he could get them to mature by the end of the season. Each player could have been a star on his own, but he got them to share the ball and believe in the idea that winning beats stats and that teamwork would set the stage for their future. The best coaches inspire and have a horizontal management style, but can also take over the team when needed. The dictatorial approach—which uses fear, power, and intimidation for strict control and direction, and which quickly deals with violations of control—cannot work long term in a creative environment. Study the best coaches’ approach to motivation and game plan, and it will help you learn how to get the creative people in your business to win your version of the Super Bowl or NCAA playoffs.

The dictatorial approach of fear, power, and intimidation cannot work long-term in a creative environment.

An orchestra conductor also manages an integrated team of musicians. Getting the string, woodwind, brass, and percussion sections to play in harmony is as challenging as working with any team or group. Each part of an orchestra is similar to a different discipline. Directing a movie, TV show, or play is also similar to managing an integrated design team. Directors must work with actors, cameramen, set and costume designers, special effects designers, and film editors. This diverse group of people must be brought together to produce a seamless piece of entertainment, often dealing with very large egos. All of the cost constraints and timelines that product programs face, film producers and orchestra conductors also face. The director and conductor are right in the middle of all of it.

The more understanding a manager has of the user-centered iNPD process, and the more experience with its application, the better will be the manager’s ability to efficiently guide the process. Each time through the process, the manager should perform a self-assessment that leads to feedback used to modify future approaches, actions, and the process itself. We have perfected our own approaches to management of design teams through experience, evaluation of our performance and the team’s performance, and continued iteration.

Let the Team Become the Experts

By the end of the second phase of understanding the opportunity, a team should know more than any manager about that particular program. A manager must learn to question the assumptions and ask for proof or clarification without telling the team what to do. The manager must learn to argue for the customer as well as the company and the team. It is important to help a team recognize why a seemingly “good” solution that does not fulfill the requirements set forth from the VOA might not be the most appropriate for the program.

Sometimes the manager has insight from years of experience that can assist the team. More often, the manager finds that the team is lacking expertise in a certain support area. In that case, it is the manager’s job to establish help through a support network. Such a network can be built up throughout a company or, for smaller companies, outside the company structure.

Recognize the Personality and Needs of the Team

Teams have very different personalities. They work together in a variety of ways. The best high-performance teams require very little maintenance. Some teams are that way from the start. All teams should reach this level by the end of the second phase. We have seen many types of team dynamics, as discussed earlier. The manager must recognize and manage the overall team personality. The team must function as a whole. It tends to develop its own group personality, but the team is still built of individuals. Individuals have their own needs that range from being recognized for their effort to needing help in overcoming personality differences with others. The manager must also recognize individual needs and nuances and work with the individuals and the team to create a positive iNPD environment. It is important that criticism be constructive and productive.

Use of an Interests-Based Management Approach

The members of a product development team are a vital resource to the future of a company. They are a set of creative individuals with the knowledge needed to develop the future capability of a company. They are as important to a company’s success as a set of actors is to a movie, musicians are to an orchestra, and athletes are to a team. With the shortage of talent at this level and the need for new products and services, employees know that their services are a precious commodity. Fostering their sense of self-worth and commitment to a project and a company is an important part of managing. People inherently want to do well and be part of a process that they feel integral to. A hidden part of the role of a manager is helping to foster a positive relationship between the employee and the company. Given that long-term loyalty by employers and employees is not the guarantee that it was in the middle of the twentieth century, the manager is the short-term representative of the company for optimizing loyalty and commitment for the duration that someone works for a particular firm. One of the most rewarding experiences for a manager is to transform a group that is perceived as mediocre into a high-performance team.

This current business atmosphere requires a management style rooted primarily in interests and, at times, rights, and requires a thoughtful use of power only as a last resort. Managers must help teams reach decisions using the customer’s interests and sometimes different disciplines’ rights. Only when teams are hopelessly deadlocked should management power come into play. Managers need to empower the team with the ability to make decisions, and every use of power is a potential threat to the team’s morale. As teams become experts, a manager must trust the insight of the team because the team members together will normally surpass the knowledge of the manager. Managers need to let that happen. Managing today has more to do with responsibility than power. Building trust and clear communication with a team is more important than forcing them to take directions that the team does not develop on its own. The approach of balancing interests, rights, and power can work in a Burger King as well as the auto industry. You might be able to use an approach that relies more on power in the fast food industry, where pay, morale, and dedication are low and turnover is high, but when you are managing a team with the range of fields involved in the product development process, the power approach will have detrimental effects. People might work hard for a manager who uses power, but they will never work creatively. The use of power might help teams make deadlines and hit cost targets, but it will not help teams achieve a breakthrough that has insight and produces true product value to the customer. Only through the use of an appropriate balance of an interests, rights, and power approach can managers hope to move the products produced by their teams to the Upper Right.

We are not saying that power plays no role in the process. Dr. Peter Johnson, former chairman and CEO of TissueInformatics, has said that doctors are educated to be Athenian and Spartan. They are usually Athenian when working with others. They use a diplomatic approach to problem solving: When a surgeon is operating, he needs to have a good team atmosphere. Sometimes, however, emergencies arise and decisions must be made quickly. Doctors in this type of life-saving situation must become Spartans and make quick, decisive decisions. Similarly, at times management must step in and recharge, redirect, and reprimand a team. Knowing when to shift from Athenian to Spartan is part of the art of managing. The Spartan approach should be done in a nonthreatening way, and the relationship of trust between managers and teams should allow for direct and clear exchanges that re-energize the teams.

Visionaries and Champions

Although day-to-day managing is critical, it is important to recognize the role that vision plays in developing successful products. Coupled with vision is the role of being a champion for a product program. Sometimes it seems that companies feel that they can just plug in the numbers and use methods in a distant and detached way, and the process will take care of itself. At other times, companies fail to recognize the role that key people have played in keeping a dream alive and maintaining an atmosphere that fosters excellence. The methods and ideas we describe in this book are important for any new product program. However, the greater the vision is at the top, the easier the process will flow. The greater the ability for top management to infuse the rest of the company with that vision, the better all projects will run. In contrast, failure to champion the insights of a team will push the best process dangerously off course.

Often product programs hit go/no-go decision gates or places where major assumptions are challenged. In the course of doing research for this book, we have come to understand how important it is to have a visionary who acts as a champion when these major events occur. A visionary has a broad sense of the mission and goals of the program and trusts the people charged to carry it out. The team is infused with a sense of commitment and enthusiasm. When the team clicks, the visionary knows it. At key design points, the visionary manager can support the team and allow it to overcome a challenge by keeping core ideas intact. Conversely, a visionary can also critique a team successfully and offer suggestions because the team trusts that person’s motives.

Summary: The Empowered Team

Managing interdisciplinary teams is hard but rewarding. It takes patience, adaptability, and flexibility. Managers must understand people as well as disciplines. They must be willing to learn new ideas and trust in the team’s ability to get the job done. As the product development process is user centered, team management is people centered. Learning to be a team manager takes time. The teachings and methods of this book, coupled with experience gained from trial and error, are the best tools for taking on this exciting challenge. The reward is a team of individuals who come together and produce a successful product or service that no one discipline could have ever produced alone.

iNPD Team Integration Effectiveness

This chapter began with a goal of converting members of independent disciplines (see Figure 6.1) into an integrated team, as shown in Figure 6.2. Four major elements were presented to assist in this integration:

• The need to overcome perceptual gaps between team members of different disciplines

• Ways to optimize team functionality, including negotiation strategies that focus on users’ interests

• The allocation of parts of a product in the Part Differentiation Matrix, based on lifestyle impact and complexity, to understand where true integration is necessary and when different disciplines will take the lead in the development process

• Management strategies that empower the team to function independently, as appropriate, through the development process and that respect individual disciplines

As Figure 6.16 shows, each of these elements works collectively to enable an effective iNPD process. Effectively addressing these components results in a high-performing team that enjoys the process and is poised to develop a breakthrough product.

Figure 6.16. Four elements to effective iNPD team integration.

Although this might seem ideal, our experience is that this model works. Teams that integrate quickly and fundamentally consistently excel in the product development process, producing great products that meet or exceed cost and time constraints as well as performance and quality specifications. For the process to work, however, the team needs to understand the interests of the user as a basis for critical decisions. The next chapter focuses on techniques to develop a common shared understanding of a target user.

Summary Points

• Perceptual gaps between team members from diverse functions exist and must be overcome.

• An effective use of interests-based negotiation is critical to the long-term success of a team; power is a last resort that management should use only sparingly.

• The user’s interests should drive critical decision making.

• The Part Differentiation Matrix helps teams understand where parts integration is critical and when engineering or design should take the lead.

• iNPD team members must respect all other disciplines that participate in the team and appreciate each contribution to the overall process.

• iNPD teams should be managed through empowerment and support, recognizing that all disciplines have an equal voice in the overall process.

• High-performing teams enjoy the process, improve their potential of success, and carry their positive experience to other programs.

References

1. J. Cagan, C. M. Vogel, and L. R. Weingart, “Understanding Perceptual Gaps in Integrated Product Development Teams,” in Proceedings of the 2001 ASME Design Engineering Technical Conferences: Design Theory and Methodology Conference (Pittsburgh, PA: 2001).

2. L. R. Weingart and K. A. Jehn, “Manage Intra-team Conflict Through Collaboration,” in ed. E. A. Locke, Handbook of Principles of Organizational Behavior: Indispensable Knowledge for Evidence-Based Management, 2d ed. (Chichester, U.K.: Wiley, 2009): 327–346.

3. W. L. Ury, J. M. Brett, and S. B. Goldberg, Getting Disputes Resolved: Designing Systems to Cut the Costs of Conflict (San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1988).

4. L. R. Weingart, M. A. Cronin, C. J. S. Houser, J. Cagan, and C. Vogel, “Functional Diversity and Conflict in Cross-functional Product Development Teams: Considering Representational Gaps and Task Characteristics,” in ed. L. L. Neider and C. A. Schriesheim, Understanding Teams (Greenwich, CT: IAP, 2005): 89–110.

5. J. R. Katzenbach and D. K. Smith, Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High Performance Organization (New York: Harper Perennial, 1994).

6. S. R. Covey, Seven Habits of Highly Effective People (New York: Fireside, 1990).

7. J. Kao, Jamming: The Art and Discipline of Business Creativity (New York: HarperBusiness, 1997).

8. M. Csikszentmihalyi, Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (New York: Harper Collins, 1991).

9. J. Wooden and J. Carty, Coach Wooden’s Pyramid of Success: Building Blocks for a Better Life (Ventura: Regal, 2005).