4. Organizing for Innovation: How to Structure a Company for Innovation

Organizing for Innovation

Organizing for innovation continues to be a challenge for many companies. Crafting a strategy or building innovation processes is not enough; you need to build and embed innovation into the overall organization. Successful innovation requires choosing, building, and preparing the right organization and the right people for executing and scaling the innovation.1

Many large firms have struggled and, by their own description, failed in the attempt to integrate innovation into their organization. They often find that the organizational components of innovation are rejected or marginalized by the mainstream organization. Organizational antibodies are released that kill off the innovations and often the structures, resources, and processes responsible for the innovation. Because of this, some believe that it is not possible—or, at least, much harder—to innovate successfully within the structure of a large, established organization.2

Developing an Internal Marketplace for Innovation

One of the main approaches to ensure that innovation is successful in your organization is to develop an internal marketplace where the ideas and functions of innovation can flourish in a supply-and-demand environment. In this innovation market, the true commercial value of every idea is reflected in the management attention and funding it receives. Truly valuable innovations are funded and advanced to commercial realities, no matter how threatening they may be to the existing businesses or how difficult they may appear.

For example, Bank of America, like other large U.S. banks, faced a new challenge in the twenty-first century: With the opportunities for further acquisitions narrowing, it needed to find a way to grow organically by attracting more customers and fulfilling a greater share of their banking needs. It created the Innovation & Development (I&D) team, a corporate unit charged with spearheading product and service development at the bank. The team’s immediate goal was to pioneer new services and service-delivery techniques that would strengthen the bank’s relationships with branch customers while also achieving a high degree of efficiency in transactions. Bank of America decided to take an unprecedented step in the conservative banking industry: It would create an “innovation market” within the bank’s existing branches, whereby it used its locations to launch various experiments without redesigning its branches. This approach provided a true test of the potential market value of innovations.3

Critical to creating such a marketplace is balancing creativity and value capture so that both thrive. Ultimately, this internal marketplace for innovation and a balance of creative and value capture may be more important than the organizational design you select. An entrepreneurial drive for innovation brought about and supported by strong internal market forces can overcome many organizational barriers.

Balancing Creativity and Value Creation

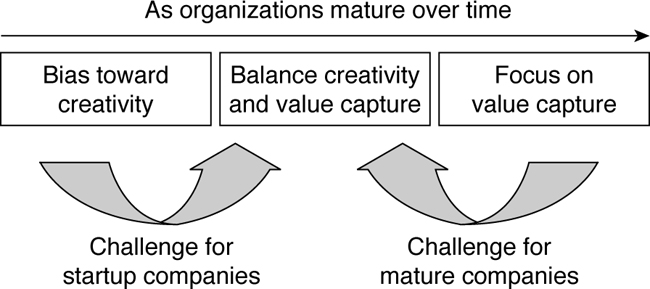

In a company where innovation thrives, you can be sure that both the creative and value capture (commercial) functions are operating at full tilt. Management—as well as the entire organization—recognizes that successful innovation requires a balance of the creativity and commercialization processes (see Figure 4.1). Typically, these companies have developed their own internal marketplaces that weigh, select, and prioritize innovations for their creativity and inherent commercial value or worth to the company. CEMEX created an internal marketplace for innovation where ideas are developed, selected, and funded in an environment that honestly values the worth of an idea. Senior management oversees the market to ensure that organizational antibodies and other forces do not skew the market’s perception of potential innovations and to make sure that funding for commercialization is not out of line with the true potential of the innovation. Inside the company, innovators actually “sell” their creative ideas to management, embodied in R&D projects, product-development collaborations, new business models, and strategic alliances. The internal market works like this: If management likes what it sees, it funds the projects based on their perceived commercial value to the company. Otherwise, management holds back on funding.

Figure 4.1. Innovation requires a balance between creativity and commercialization.4

The Balance Changes as the Organization Matures

In the business world, there’s a natural evolution in the relationship between creativity and value capture as companies grow from emerging to mature. In the earliest stages, a company is focused on creating new, improved products or services. At that point, the attention to maximizing the value capture (such as faster, better, cheaper delivery) is relatively low. This is the problem with some startup companies. In the later stages of growth and maturity, the singular drive to be creative usually decreases and is replaced by a shift to increasing value capture—improving the process of executing, delivering, and selling its portfolio of products and services (see Figure 4.2):

Figure 4.2. The challenges of balancing creativity and value capture

• Displaying bias toward the creative process. Emerging companies typically place a higher premium on creativity. Their internal markets are biased toward the radical ideas and breakthroughs that can come from the creative process and can leverage the young company into a competitive advantage. Many startups abound in creativity and radical new business models. For example, E*Trade was a radical new approach to the traditional financial trading business that offered a fresh new way to view how small investors can enter financial markets—with significant changes in both the traditional technology and the business model.

• Balancing creative and value capture. As companies grow and mature, they learn to balance their creative processes with solid commercialization skills. It’s a question of survival. Radical new business approaches are not enough to make a company succeed. The company also needs excellence in execution and the ability to commercialize innovations that flow from the creative processes. At first, B2C (business to consumer) Internet retail outlets, such as eToys and Amazon.com, experienced extremely high multiples because of the vitality of their breakthrough creative outputs. But Wall Street and some clicks-and-mortar competitors sent clear signals that commensurate commercial capabilities were also needed. Likewise, TiVo created a new market category with its digital video recorder but faces increasing pressure to demonstrate that it can strengthen its value capture in an increasingly competitive arena. For TiVo and many other companies that exploded onto the scene with innovative ideas, transitioning to a greater focus on value capture is not just an evolutionary next step, but a matter of survival. Competitors with strong supply chains and customer connections have moved into the space created by the innovator and may take it over.

• Focusing on the value capture. As companies continue to mature, the emphasis on commercialization surpasses the attention to creative markets. The management mantra becomes “Profitability, asset utilization, capital management, efficiency, benchmarking,” all of which place more value on the value capture process. Creativity, especially radical creativity, has decreasing value or even negative value as the company settles into maturity and must fight for market share. Traditional grocery companies fell into this category, and Webvan challenged their execution-oriented, value-capture mentality by introducing a radical new approach. Interestingly, Webvan failed commercially, but some traditional grocery companies, such as Safeway, adopted its business model and technology innovation, benefiting from an infusion of creativity that they did not receive from their internal marketplace.

Mature companies with strong commercial yet weak creative functions measure innovation in terms of discounted cash flow (DCF), return on investment (ROI), hurdle rates, and payback, none of which support creative activities. In many of these companies, incremental innovation is the norm. Radical and breakthrough ideas disappear—and so do the people responsible for them. Having adequate measurement systems is key to avoiding this bias, a topic covered in depth in Chapter 6, “Illuminating the Pathway: How to Measure Innovation.” For example, an executive at a major auto company that was launching an innovation initiative listened carefully to the description of personality types he would need to hire to help rejuvenate the creative internal markets and offset the existing commercialization bias. His response was, “We fired all those kinds of people years ago.” He was right. In the drive for excellence in value capture, his organization had removed the entire creative function.

Some potentially successful innovations in mature organizations fail because they never find a marketplace inside the company that recognizes and supports their inherent value. How many times have we heard stories about great products or business concepts that failed to get internal buy-in, only to have the innovators spin out and create a successful company? Far too often. For example, Conner Peripherals spun out of Seagate Technology and subsequently commercialized a new, smaller (3.5-inch) disc drive technology that became the major new technology in the disc drive markets. Seagate management had looked at that same technology but had not seen its potential value or funded commercialization. Likewise, in the 1980s, Boston Consulting Group (BCG) spun out of Arthur D. Little (ADL) and brought its special brand of portfolio management to consulting. ADL did not see the value in the BCG business model, and BCG could not see letting the opportunity pass. During the next 20 years, BCG grew and eventually surpassed ADL in size. If you look for failed innovation initiatives, you will often find innovation deals that were never consummated because the internal markets were limited. The problem is rarely that a company is risk averse, blind, or resource constrained. Instead, it usually rests in the lack of a properly functioning internal marketplace for certain types of innovation.

These symptoms illustrate a company whose internal marketplace values incremental changes to the existing products, processes, and business models rather than radical change, breakthrough technologies, or new business approaches.

Five Steps to Balancing Creative and Commercial Markets

The best process for balancing creative and commercial processes includes five steps:

1. Develop innovation platforms for the different types of innovation you want to pursue. These innovation platforms act as organizing principles for innovation. (Innovation platforms are very important, and a deeper description is provided later in this chapter.) Innovation platforms cut across the business unit silos and provide an honest perspective on the value of the innovations rather than one limited by the perception of a single business unit. For example, Canon used innovation platforms to leverage its optics, electronics, and precision manufacturing capabilities in its existing organization to launch into business equipment. The outcome was an efficient use of resources and competencies for existing and new businesses.

2. Create portfolios of projects in each platform. Each project needs to be reviewed to ensure that the creative and commercialization markets are aligned and balanced. A portfolio that is overly rich in incremental projects signals an anemic market for creative ideas. A portfolio that has an overabundance of radical and breakthrough innovations signals a hyperactive creative process and an internal market that discounts commercialization.

3. Form internal and external partnerships and networks. Internal and external partners are essential to success. Today, leading companies such as Cisco and Millennium Pharmaceuticals work aggressively to complement their internal talent with their partners’ capabilities.

4. Ensure that markets for creativity and commercialization are open and transparent. The last thing you want to do is create a closed internal market for either creativity or commercialization. Closed markets create an air of mistrust and can hide inefficiencies and inequities. Create semiannual innovation events that provide visibility and total transparency. Make the events open to everybody, and make sure they’re highly publicized. Send the signal that value creation via innovation is a vital part of the culture. Google has created a culture where innovation is the norm and where the employees value and expect open, full exploration of potential innovations.

5. Guard against organizational antibodies that may limit or destroy your rejuvenated creative markets and processes. High-level senior executives should be part of an Innovation Board in charge of rejuvenating the creative market. Such visible support is necessary to offset the inherent resistance to change in the established commercialization market. Otherwise, many in the organization will view a revitalized creative market as folly or a waste of resources.

Rejuvenating the innovation process requires a significant change in mindset, support from top management, and a reallocation of resources. But if you approach the task with the same mindset as Groucho Marx did, you will find that innovation results from the perfect balance of the creative and value capture processes. Remember that how you innovate determines what you innovate.

Outsourcing Innovation

At the most basic level, the choice of structure—how to organize yourself and your people—for innovation is a choice between internal and external options.7 Options for internal structures for innovation include funding traditional R&D departments, setting up centers of excellence, creating separate business units for innovation, and using incubators.8 External structures for innovation are based on outsourcing to different partners—suppliers, customers, and others.9 Different structures are appropriate for different types of innovation.

Many companies are asking, “Should we outsource our innovation?” That is the wrong question. The right questions are: In which parts of our innovation should we partner? How much should we rely on partners and how much should we take on ourselves?

Innovation is too important to outsource completely. Partial outsourcing, better termed partnering, is a solid, proven approach to enhancing innovation (see the following section, “Making Good Use of Your Partners”).

Partnering is a standard and potentially valuable part of the innovation toolbox. Reaching outside for additional resources, ideas, expertise, and different perspectives can be highly valuable when combined with the internal ability to understand and use what your partners bring.

Examples abound of effective open innovation partnering structures.10 The following are a few:

• Intel has opened four small labs, or “lablets,” near university campuses in the United States and Great Britain to promote an exchange of ideas between the lablet and the university. Innovative ideas are expected to come out of the newly opened lablets. Eli Lilly recently launched an online knowledge broker called InnoCentive,11 where it and other firms post R&D problems and solicit solutions from companies and individuals worldwide.

• Schlumberger sells innovative ideas in the area of oil field services to both customers and competitors. Ideas include ways to reduce drilling costs and increase data on reservoir characteristics collected during drilling. The company once sold its innovations only to customers, but selling to competitors as well now allows it to profit from its ideas in any oil well anywhere in the world.

• IBM uses excess capacity in its semiconductor fabrication facilities to manufacture chips for other companies. Recently, the company also started offering design services and now designs and manufactures some competitors’ chips.

• Dreyer’s Grand Ice Cream sells the use of its logistics and distribution system to competitor Ben & Jerry’s. The system tracks retailers’ inventory at the checkout scanner, automatically places restocking orders, and bills the retailer. Sharing its system with another supplier spreads Dreyer’s overhead costs across more volume and encourages additional retailers to adopt the Dreyer’s system because of its higher volume.

• Procter & Gamble thrived for years while relying on the 7,500 employees in its R&D group to crank out new products. But as the pace of innovation elsewhere increased, P&G faltered. To fix this problem, CEO A. G. Lafley has decreed that half of the company’s ideas must come from outside, up from about 10% when he took over in 2000.12

At one time, companies relied primarily on internal resources for innovation. The technology giants of the last century—DuPont, General Electric, IBM, Xerox, AT&T—relied on an innovation recipe that consisted of internal laboratories, brilliant minds, and, ultimately, the flow of great ideas and successful innovations. But from the 1980s onward, the companies that have flourished—including Cisco, Intel, and Nokia—have not relied on the internal lab and increasingly have used and acquired outside resources for their innovation. Ironically, one of the biggest companies, Microsoft, has developed an internal research lab of scale and power to rival the labs of yesteryear.13

No one has ever doubted the power of assembling bright people in an organization and encouraging them to do great things. However, the downside risk is that the inside organization will be too inward looking, will discount the innovations and mental models of others, and will lose the cutting edge. Microsoft’s innovation strategy must address this risk at some point. Even with a large, internal innovation capability, a company cannot go to market and hold a dominant position without the meaningful collaboration of many other organizations.

Making Good Use of Your Partners

Developing, maintaining, and using strong relationships with partner organizations can be a key competitive advantage in innovation for your company. For example, instead of the usual R&D unit testing new products, try outsourcing innovation testing to your customers. Microsoft often avoids partnering but has relied heavily on this technique in the past,14 using its customers to beta-test its new products.

Universities such as Stanford are potentially valuable partners because they are prolific sources of new technologies and business models with sizeable market opportunities. But in contrast to for-profit companies, universities do not consider commercializing their ideas directly. Their way to capture some of the value of these ideas is through licensing agreements in which they sell or license the technologies for other parties to bring to market. The Office of Technology Licensing at Stanford University fulfills this role. This office helps researchers find partners that are interested in transforming the ideas into value. Partners can also include venture capitalists for more radical technologies.

Open-source software-development projects—Internet-based communities of software developers who voluntarily collaborate to develop software that they or their organizations need—have become an important economic and cultural phenomenon, and they exemplify the changing role of partnerships in innovation. SourceForge.net, a major infrastructure provider and repository for such projects, lists more than 10,000 of them and more than 30,000 registered users. The digital software products emanating from such projects are commercially attractive and widely used in business and government (by IBM, NASA, and others). Because such products are deemed a public good, the open source movement’s unique development practices are challenging the traditional views of how innovation should work.15

Creating and maintaining truly effective partnerships is one of the least well-understood aspects of innovation. The problem is a lack of structure in framing and selecting the type of partnership required. The truth is that there are many types of partnerships, and a company should be very careful in selecting the one that fits the needs.

Each type of partnership requires different goals, performance metrics and incentives, conflict resolution, and governance. It also requires recognition that the partnering organizations are different (for example, culture, business objectives, performance metrics, and incentives) and that getting them to work together cohesively takes some planning and effort. Partnerships deliver in direct proportion to the adequacy of their structure and management.

Integrating Innovation within the Organization

Having certain innovation functions, such as ideation, outsourced may speed up the innovation process. Ideation is the development of good ideas that can be turned into innovations. Mattel, Wal-Mart, and other toy manufacturers and retailers use idea brokers like Big Idea Group16 to scout on their behalf for new ideas. Big Idea Group takes submissions and refines and pitches the more promising ones. Big Idea Group has placed a number of toys with companies like Basic Fun and Gamewright.17 The outsourced company may create ideas for innovations, but the original organization still needs committed resources within its innovation group to take the ideas to the next level.18 One example of this is Chevron, which uses Process Masters, employees with specialist skills and excellent knowledge of various parts of the organization. These Process Masters meet in small groups and are responsible for identifying and transferring internal innovations around the company. They also track external capabilities and innovations that are used for internal solutions, thus utilizing the best of both worlds.

The Value of Networks and Innovation Platforms

Many CEOs ponder how to organize innovation within their company. Creating and maintaining the correct structure is admittedly hard to do. Even companies that have achieved truly creative innovation centers have seen them falter and even collapse at some point; consider the ups and downs of Apple Computer and Lucent, just to name two. However, there are lessons to be learned from the companies that have succeeded. The key is to throw away a major misconception and to adopt a new organizing principle. This does not preclude leaving room for individuals or teams to spend limited time in self-directed exploration like 3M or Google.

The major misconception is that innovation is present everywhere in the company and that all employees, partners, and customers should be part of the process all the time. Innovation does not exist evenly everywhere in the company; it exists in hugely disproportionate quantities across the organization at any given time. Some individuals are very good at it, and some are not. Innovation is not a quality initiative in which it is necessary to make innovation everyone’s job all the time to be successful. Those who are creative and good at innovation will become frustrated at a process that dilutes their efforts with largely untalented people. Also, innovation should happen preferentially in areas that have been targeted in the strategy. It would be unwise and wasteful to encourage people to spend time on innovation in areas where they do not intend to follow through with investments because the strategic and financial returns would be unacceptable.

A key step to creating or maintaining innovation in an organization is to discard the idea that absolutely everyone must be involved all the time. In some organizations, including everybody in the process may overwhelm the process and could be counterproductive. Let everyone have access to and participate in the innovation process, but make it clear that you do not expect everyone to participate equally all the time.

That being said, it is not enough to avoid creating the “Peoples Republic of Innovation,” where all are equal. In addition, it is not enough to simply hire and sponsor creative individuals. To create sustained innovation excellence in your organization, it is necessary to create innovation platforms and networks of individuals within them where the selected innovative individuals can share with each other, be managed, and grow. Overseeing the building of innovation platforms and networks to manage the resident talent and to let the best emerge and grow is management’s responsibility.

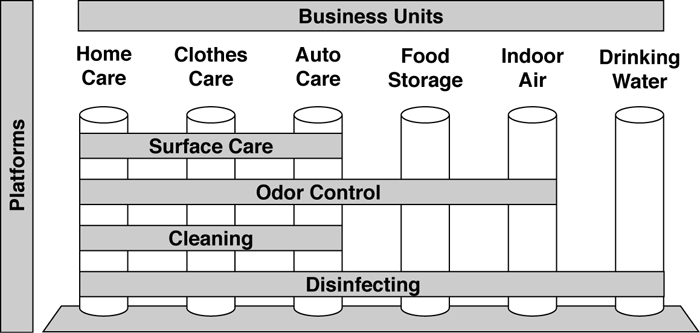

Many companies, including Johnson & Johnson and Alcoa, use innovation platforms. Innovation platforms provide the organizational basis for innovation, from incremental to radical, by focusing resources on innovation and providing processes for managing innovation. Innovation platforms are organizational units of networks nestled within a company that direct resources toward specific areas of innovation. Resources dedicated to operations cannot break away from those duties to perform innovative functions. And resources dedicated to innovation—cut off from the realities of operations, markets, and finances—cannot efficiently produce valuable innovations. Platforms allow the organization to share in both operations and innovation, and networks provide the channels for communication and collaboration. Networking is widely used inside J&J, in part because it is highly decentralized. ALZA has learned since its acquisition to act as a networker inside J&J, leveraging its knowledge and expertise of drug delivery platforms to create innovations with low transaction costs. And because it produces more value for less cost than other approaches, Hewlett-Packard uses extensive networking across its selected innovation platforms.

Innovation platforms include these:

• Broad areas of innovation (such as surface cleaning in one leading consumer goods company and improved wound treatment in a medical products company) that direct the platform’s activities:

• Both business model and technological change

• A portfolio of incremental, semi-radical and radical innovations

• Networks of people inside and outside the organization who can effectively contribute to different aspects of innovation—idea creation, selection, development, and implementation—that span the range of business and technical challenges. They also preserve the intellectual capital and knowledge in the company during downsizing.21

• Metrics and rewards that do the following:

• Focus the resources on the potentially valuable areas of innovation that are consistent with the innovation strategy.

• Capture the innovation performance of the organization and highlight the gaps and areas for improvement.

• Encourage the desired behavior and results and mitigate organizational antibodies.

• Management systems that promote and use learning and change to improve all aspects of innovation—strategy, processes, organization, and resources.

Figure 4.3 depicts innovation platforms that span the six business units of an organization. Innovation platforms, such as surface care and cleaning, span three business units and support each. These platforms contain innovation efforts, incremental through radical, that can be applied to all three business units. This limits redundancy between the business units and also provides a portfolio of innovations that the business units can draw upon as needed to meet their business objectives. Some innovation platforms, such as odor control and disinfectancy, span more business units. These innovation platforms are common to a greater number of business units but supply the same efficiency and portfolio efficacy of the smaller platforms.

Figure 4.3. Example of innovation platforms and business units22

Ford Motor Co.’s iTek Center in Dearborn, Michigan, an $80 million investment, brings together teams from the business, design, and technology divisions to work on initiatives. Ford’s goal is to plan, develop, and test a process or a technology application within a 90-day window.

Funding for innovation should vary based on who stands to benefit. At GE, individual businesses contract with the R&D center on enabling technology projects that let the businesses develop their next-generation products and services. That’s about 60% of the budget. Thirty percent comes from CEO Jeffrey Immelt for longer-range technologies, projects that are five to ten years out. The final 10% comes from external contracts, typically with the U.S. government. For something like nanotechnology (which is a platform that has the potential to impact four or five businesses at GE but takes long-term, high-risk research to realize that potential), funding comes directly from Immelt’s office rather than from the individual CEOs of each of GE’s 13 business units.23

In addition to innovation platforms, innovation can be organized internally using alternative organizational models.

The Corporate Venture Capital Model

Corporate Venture Capital (CVC) is a model of innovation inspired by external venture capital firms. It is a useful model to consider for promoting radical innovation in your organization while not hindering incremental innovation. The basic premise of CVC is that, to promote the development of commercially viable innovations (especially radical innovations) within your organization, you need to have a mechanism in place that evaluates potential innovations in the same way that an external venture capital firm would.24 ChevronTexaco’s venture capital group invests in innovations that are outside the domain of traditional energy company R&D but has potential value to ChevronTexaco.

CVC works as a hybrid between an independent venture capital firm and an incubator within the organization (see Figure 4.4 for a description of an incubator).

Figure 4.4. Overview of an incubator structure25

Typically, a venture capital team within an organization consists of a number of senior executives from different areas (technology, marketing, operations) and a select few external partners. The external members might be key suppliers or customers, or possibly even a venture capitalist with whom the organization has developed a relationship in order to benefit from its experience and expertise. The venture capital structure receives the radical ideas, selects those with the most potential, funds them, and then sells them. In fact, a venture capital arm within an organization acts as a radical innovation hub. An option is to have the CVC division scouting the company for ideas. This alternative requires a very well-networked division so that people with ideas feel comfortable talking to the experts. It is like an internal VC that funds ideas that look promising.

The Ambidextrous Organization

The theory of the “ambidextrous organization” suggests that an organization promotes innovation and operations within its architecture through multiple groups handling different types of innovation and operations projects, thus promoting different cultures and processes for innovation needs.26 In this way, radical innovators are kept separate from the traditionalists who run the core businesses. IBM used this approach to grow its new consulting businesses while maintaining the strength in its heritage hardware businesses. This type of separate structure is successful because different types of innovation require different types of systems, resources, and culture.27 However, there are concerns about the ambidextrous organization. Is it viable? Or do organizations need that level of separation to be successful?

Some organizations have tried to insulate the innovation function by setting up a completely separate business unit. They establish different rules and culture for this business unit to foster creativity and innovation. Whether the company uses a corporate venture capital model or simply identifies a potentially successful radical innovation, moving it to a separate structure (even location) protects the project. With this structure, the project is treated as a startup even if it is part of a larger company.

Innovation teams are often allowed to operate in isolation from the company and its traditional business scrutiny. In other words, the teams must be allowed to perform, much as Lockheed’s famed skunkworks did when making radical advances in spy planes in the 1940s, as separate workgroups unencumbered by corporate restrictions. Today companies such as DaimlerChrysler, BMW, Matsushita, and Microsoft have insulated their teams in Silicon Valley. Being insulated allows and encourages the team to break the rules and, most importantly, protects it from organizational antibodies.

Ideally, isolated units must have access to the brains and resources of the larger organization while still being insulated from the negatives such as organizational antibodies and distractions. However, separation sometimes results in isolation from all aspects of the organization, good and bad, rather than insulation from the bad elements, such as organizational antibodies.

A large international engineering company with a separate e-commerce unit has experienced great difficulty in selling its collaborative design and build product to clients. The main reason for the difficulties is that the company’s employees are suspicious of the separate business unit and do not promote it to clients. The separate unit has processes and templates that are not fully integrated with the bricks-and-mortar processes. The idea of e-commerce is not integrated into the company culture and, therefore, is not utilized as a tool as it was intended.

By separating innovation into separate business units or outsourcing it, you may be significantly limiting the amount of information on innovation that is available to the organization. As illustrated by the previous example, this can have several negative consequences. If people are not aware of the range of innovation projects, the potential value of innovation, or how the general process works, several negative things can happen. There is a higher likelihood that innovation will not be an integral part of the culture and that organizational antibodies will arise to challenge the innovation after it is introduced in the marketplace.

An alternative is to integrate the new business model into the existing organization. Traditional bricks-and-mortar organizations such as Charles Schwab and GE have opted to fully integrate e-commerce into their organizations, with great success. This is in contrast to others, such as Barnes & Noble, that created a separate e-commerce organization that has experienced some major problems due to lack of integration.

In addition, some instances of this result in a disconnection between the innovations and management’s perception of what is needed. In part, this is the problem discussed earlier of the internal market for innovation because the perceived value of the innovation may be artificially suppressed. However, it also challenges two innovation rules: neutralize the organizational antibodies and provide strong leadership of the strategy and the portfolio. If challenges to the innovation rules occur as a result of a separate organization, it could significantly diminish the return on the innovation investment and may actually threaten the viability of long-term innovation in the company.

The Leadership Role

Sometimes the CEO designates a chief innovation officer to serve as manager and advisor on innovation matters. Alternately, the CEO can fulfill the role of the CIO. Either way, the leadership role includes these roles:

• Providing a long-term view for innovation via the innovation strategy and portfolio

• Sensitizing key leaders and managers to the dynamics of innovation

• Nurturing key creation projects

• Managing relationships with external partners

• Assessing innovation implications of corporate, strategic initiatives

• Providing an expert opinion and crucial judgment

• Managing the balance between business and technology innovation, such as organizational dynamics, portfolio, resources, and processes

It is a fundamental truth that every innovation requires the support of a manager to survive. Initially, this manager person may be a middle manager who has the decision rights, criteria, and risk behavior to support the early stages of development. Also, the manager must have sufficient resources to fund ideas that have some potential.28 A lean organization may be good at incremental innovation, but it may fail in radical innovation where it needs more experimentation and risk taking. Finally, the manager has to be willing to run the risk associated with innovation—the risk of investing resources in a project that may have no returns or payback in the future.

Jeffrey Immelt urges investors and engineers to be patient with innovation. He has poured extra money into R&D at GE while loosening the timelines on projects that may not pay off for ten years or more. He says that, for established companies, investing in emerging technologies is a matter of survival. “I just see very clearly that unless you’re out there pushing the envelope and driving innovation, you’re not going to get the kind of margins and the kind of growth that we need for a company like GE. I really see it as an economic imperative.”29

It is sobering to realize that the commercialization of Post-its was dependent on a midlevel manager having the good insight and gumption to fund its development. Otherwise, it never would have happened. This takes nothing away from Art Fry and his dedicated team at 3M—they created the innovation, and Fry is well known as the “Father of Post-its.” But that midlevel manager was also one of the keys to success. The CEO needs to create the culture, organization, and management systems to allow that kind of midlevel support to happen.

Organization and the Innovation Rules

Partnering is a key innovation competency. Organizational issues regarding innovation always deal with the issue of what to do inside and what should be done outside.

Some innovation experts have stressed the need to outsource. This is the wrong emphasis. The correct place for management to place its attention is on partnerships and how to use them. Structuring the internal and external partnerships often receives too little attention. This includes defining the areas for partnering, defining who to partner with, and designing how to operate the partnership.

In addition to partnering, management needs to focus its organizational improvements on creating value faster, better, and cheaper than competitors. Value creation requires building networks of innovators that extend within and outside the organization, as Intel, Oracle, and P&G have done. These networks help integrate innovation into the business mentality by keeping innovation present in all the right places and for all the right decisions. Networks need to be organized around defined innovation platforms and focus the appropriate resources on a portfolio of incremental, semiradical, and radical innovations. This keeps them operating faster, better, and cheaper. It allows active, effective management of the resources across the organization and with partners.

No single structure is appropriate for all types of innovation. The organizational structure needs to vary based on the innovation strategy and the characteristics of the portfolio. But for an organization to innovate successfully, it needs to foster a balance of creativity and value capture. Maintaining that balance requires support from metrics and rewards, and also has cultural components. However, the organization is at the core of the internal marketplace that provides for balanced creativity and value capture.

Organizational structure influences every aspect of how innovation occurs. It is a major part of the How variable in the equation:

How you innovate = What you innovate