10. Conclusion: Applying the Innovation Rules to Your Organization

Combining Creativity with Commercial Savvy

“The key to the whole game is to innovate and to make a profit.”

—Kevin Rollins, former CEO, Dell1

If a CEO overemphasizes innovation, it can spell disaster. Durk Jager at Procter & Gamble found out the hard way that too much emphasis on innovation can displace the focus on the profitability of the business. Jager’s overzealous pursuit of innovation created significant disruptions in the organization, and the business faltered: The profits, company morale, and the share price all declined.

A. G. Lafley, the CEO who replaced Jager at P&G, did not abandon the emphasis on innovation and has successfully moved P&G toward significantly improved innovation. Under Lafley, the company continues to shift its center of gravity toward higher-growth, higher-margin businesses such as healthcare and personal care. It increased its emphasis on innovation, increased the speed of getting new products to market, and reduced its over-reliance on incremental innovations. Lafley said that Jager attempted too much too fast and indicated that the push toward higher levels of innovation had alienated some people. He said, “We don’t want to be pushing something out of an ivory tower somewhere.”2

Lafley has slowed the rate of change and regained profitability. He has demonstrated that he has a firm grasp on both the innovation and the operational side of the business, and he has led people in the company to recognize that innovation and profitability can coexist. Executing to improve innovation requires good operations.

Lafley slowed the rate of innovation to regain profitability; however, it is possible to achieve very high levels of innovation without upsetting the profit of a business. In the rapidly changing world of the fashion business, in which each company introduces new product innovations several times a year, Giorgio Armani has been steadily profitable for 30 years. Margins for his ready-to-wear fashions are among the best in the industry, and he has diversified into new lines without cheapening his brand. He has combined creativity with commercial savvy and led his industry.3

Sir Richard Branson has kept the Virgin group profitable, growing and maintaining high rates of innovation. In October 2004, he announced plans to enter space tourism with a new company, Virgin Galactic; unveiled a new online music store; and introduced an airline in Nigeria that will become the nation’s flag carrier. At the same time, Virgin Rail’s new high-speed tilting trains were being inaugurated on the London-to-Glasgow run. Branson has demonstrated that new ventures can be launched while profitably managing existing businesses.

Smart Execution

Successfully executing improvements to innovation is relatively straightforward. The seven Innovation Rules provide the basis for effective execution:

1. Exert strong leadership in defining the innovation strategy and designing innovation portfolios, and encourage truly significant value creation.

2. Match innovation to the company business strategy, including selecting the innovation strategy (Play to Win or Play Not to Lose).

3. Make innovation an integral part of the company’s business mentality, and ensure that the processes and the organization support a culture of innovation.

4. Balance creativity and value capture so that the company generates successful new ideas and gets the maximum return on its investment.

5. Neutralize organizational antibodies that kill off good ideas because they are different from the norm.

6. Create innovation networks inside and outside the organization; networks, not individuals, are the basic organizational building blocks of innovation.

7. Implement the correct metrics and incentives to make innovation manageable and to produce the right behavior; many companies have disincentives or poor incentives to elicit the appropriate innovation behavior.

CEMEX’s CEO and senior management team took a hard, honest look at the company’s overall historic performance, analyzed the specific performance of its innovation systems and organization, and identified their vision of the role that innovation needed to play in the businesses in the future. They selected the overall portfolio of investments, defining the mix of business models change and technology change. By using the diagnostic of the innovation systems and culture, the management team identified gaps in the role that innovation needed to play versus the role it had played. They saw areas of underperformance in the company’s systems and organization, and identified the parts of their culture—including the leadership style—that needed to change. Then they developed an execution plan that defined the changes that needed to occur, the teams that would lead the changes, and the schedule for completion.

The Role of Leadership

The lesson from the most innovative companies is that leadership—particularly the CEO’s leadership—is the crucial difference in creating and sustaining successful innovation. Marc Benioff, chairman and CEO of Salesforce.com, said that it is the CEO’s role to lead the company to develop new models—business, technology, and leadership models—that will drive innovation to fuel growth and profitability. He has used this approach to lead Salesforce.com to quickly become an innovative leader in the rough-and-tumble competition of the software industry.

The leadership team should undertake three initial activities to set the context for any change to innovation.

Leadership Must Define the Innovation Strategy and Link It to the Business Strategy

The leadership team should design the innovation portfolios and identify the role of business models and technology change to lead to truly significant value creation. Upon succeeding Jack Welch, GE’s CEO Jeffrey Immelt critically reviewed the company’s business plans and identified the need for new levels and types of innovation in each business area. Immelt identified the role that innovation would play. He identified the level of incremental innovations needed to maintain the current businesses. He identified the new business models and technologies that GE needs to systematically develop within the next decade, and he prescribed increased levels of semiradical and radical innovation to spur growth and create entirely new lines of business.

Faced with lagging innovation and a depressed stock price, Kraft, one of the leading packaged foods company, launched a new innovation initiative led by an Innovation Leadership Team consisting of the CEO and five senior executives. Among other activities aimed at giving new impetus to innovation, the Innovation Leadership Team oversaw the development of the portfolio and the allocation of resources for innovation efforts. This put the leadership in the driver’s seat and sent strong positive signals to the organization about management’s desired emphasis on innovation and its commitment to the initiative.

Innovation Must Be Aligned with the Company Business Strategy, Including Selection of the Innovation Strategy

Here again, the leadership team plays a pivotal role. Although few companies in Japan come anywhere close to matching GE’s impressive record of innovation and growth, Sanyo Electric has been compared favorably to the U.S. conglomerate. The consumer electronics maker has recently transformed itself from an industry also-ran, best known for low prices, into a technology powerhouse focused on businesses where it has global markets. The CEO and chairman led the transformation; the Play to Win innovation strategy resulted in a string of new and improved products that raised operating profits 21%.

In 2004, Sanyo had transformed itself into the world’s largest maker of digital still cameras, with 30% of the market. The company led the global market in optical pick-ups—key components in DVD and CD players—with 40% market share, and Sanyo’s rechargeable batteries dominated the market and were in half the world’s cellphones. Yukinori Kuwano, Sanyo’s chief executive, and Satoshi Iue, chairman, succeeded because of selectivity about where to place its resources. “Unless you choose what to focus on, you will not be able to survive,” said Kuwano. In addition, Kuwano and Iue directed the portfolio of investments and identified the areas that were ripe for investment. “That is the interesting thing about manufacturing,” said Kuwano. “As soon as the technology breaks through or as soon as you change the business model, [something that appeared to have no future] can stage a comeback.” Sanyo’s leadership selected the Play to Win strategy and identified the roles of business model innovation and technology innovation in each of its business areas.4

Leadership Must Define Who Will Benefit from Improved Innovations

It is leadership’s responsibility to make clear to the team who are the targets for value creation from innovation. Otherwise, the company will not be aligned.

Innovation almost always focuses on maintaining or increasing profitability by delivering value to the consumer. Dell’s CEO, Kevin Rollins, says, “The true test of R&D value is, ‘Does it make a profit, and does it benefit the consumer?’ You’ve got to have both.”5

Gillette learned the hard way that delivering the right value to the consumer is not always easy. Gillette wrongly applied the “blade-and-razor” strategy to its Duracell battery business. Build a better battery, they reasoned, and consumers would trade up. There was just one problem. Most consumers did not want better batteries; they wanted cheaper ones. “Gillette made a major error in bringing innovations that the consumer did not want. It was a flawed strategy,” says Gillette CEO Jim Kilts.6

Innovation can have several other recipients. In 2004, Kraft’s big focus was on innovation—not only to persuade consumers of its products’ superior performance, but also to maintain the relationship with powerful global retailers such as Wal-Mart, Tesco, and Carrefour. Roger Deromedi, former CEO of Kraft Foods, says, “The success of Wal-Mart requires us to do more in terms of bringing true innovation to the consumer. If you are not bringing that to the retailer today, then what do they need your brand for?”7

Wall Street also can see value in innovation. In the 1990s, Dow Chemical found that Wall Street did not recognize its patent and intellectual property assets. Dow sent the clear message that it was spending wisely on R&D and innovation, that it was creating innovations, and that it was a stronger company for it today and would remain so in the future. Wall Street saw the potential value of innovation to the company, and stock prices subsequently increased.

Innovation can also be important to the network of suppliers and partners. In the 1990s, a major automobile manufacturer was considered the most innovative by the tier one suppliers. The manufacturer’s investment in innovation, its use of innovation platforms to spur incremental and more aggressive innovations, and its heavy reliance on internal and external innovation networks made it the perceived leader. The suppliers preferentially brought their innovations to that manufacturer because partnering with that company was more likely to result in a profitable new product.

Finally, innovation can also be a powerful force to attract, retain, and energize the best employees for a company. The most innovative companies are often recognized as the best companies to work for. Google’s reputation for innovation made it a magnet for the best and the brightest.

Diagnostics and Action

After these three initial steps, the leadership team should assess the company’s innovation capabilities and its current situation.

Leadership needs to ensure that innovation is an integral part of the company’s business mentality. Carly Fiorina, HP’s former CEO, said about innovation, “You institutionalize it. It is a mindset and a set of capabilities. It is about technology [and] also inventing different business models.”8 Fiorina was able to state the concept of leadership correctly, but apparently her board thought her execution fell short.

Former Siemens CEO Heinrich von Pierer launched a wide-ranging management initiative meant to instill innovation and the need to change into its business mentality. Investment analysts identified a link between Siemens’ strong performance between 2000 and 2004 and the initiative. Called Top, for Total Optimized Processes, it is credited with changing the culture of the company.9 It has resulted in a steady flow of new products and creating managers who are able to effectively use innovation to solve the operational problems.

Likewise, the leaders in Google, Apple, and 3M created a culture that builds innovation into the way the company thinks and acts. Innovation is a way of life in those companies. Ingraining it in the business mentality, through leadership and learning, has kept innovation as an integral part of the success formula.

Marc Benioff, CEO of Salesforce.com, requires that all new initiatives and products be reviewed using the V2MOM management tool. The V2MOM tool, developed during his time at Oracle and used at Salesforce.com since its founding, derives its name from the five elements of the tool:10

• Vision: What do you want?

• Values: What’s important about it?

• Methods: How do you get it?

• Obstacles: What is preventing you from getting it?

• Measures: How will you know when you got it?

The executive committee develops a company-wide V2MOM annually. Subsequently, every department and individual develops its own V2MOM that supports the company V2MOM. The tool is used to align the entire organization, from individuals to the company level. Benioff believes that the CEO should set the context for innovation and should supply the overall mandate to allow the organization to take risks; this provides the basis for incremental, semiradical, and radical innovations.

Before launching an initiative to improve innovation by using preselected tools, a company must conduct a diagnostic assessment of the innovation processes to assess the effectiveness of the key elements that maintain innovation in the business mentality: the company’s understanding of the strategy, processes, and organizational structures that support innovation. The P&G senior management team launched a diagnostic before establishing its plans to change and improve innovation in the company. This type of diagnostic provides leadership with fresh understanding of the current state of the components of innovation, gaps in actual versus desired performance, and priority areas for change.

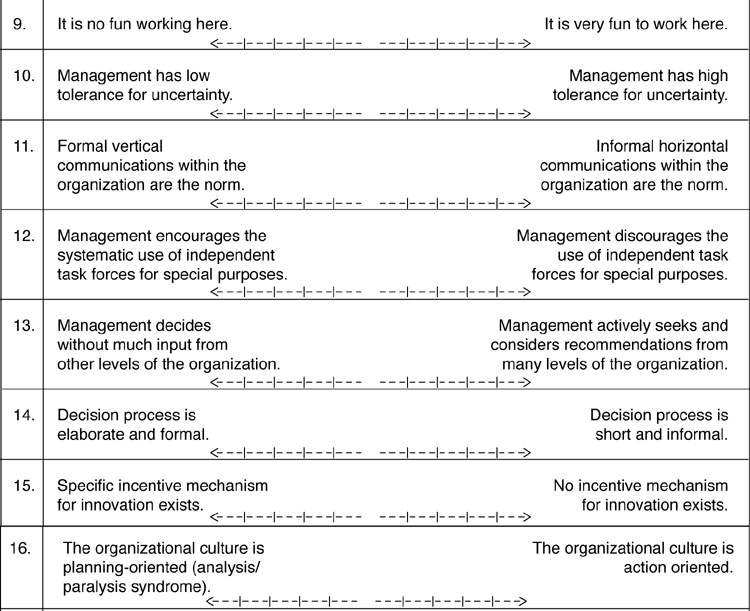

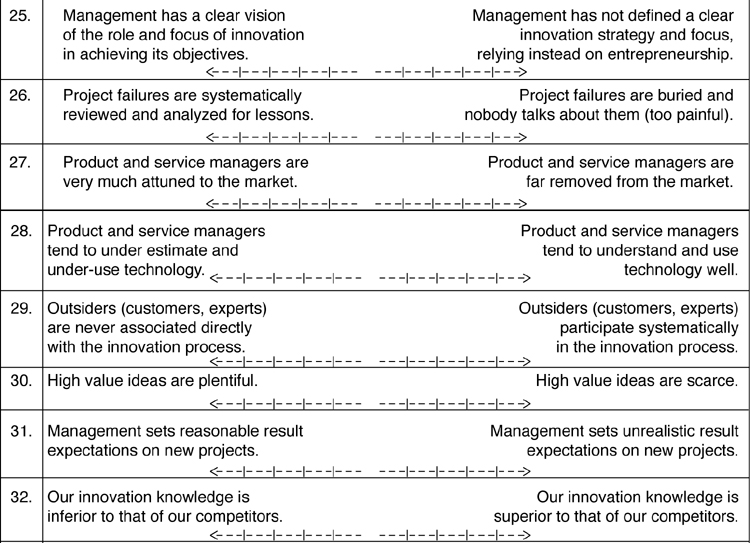

Diagnostics vary in scope. The diagnostic should fit the need. If the leadership team needs to characterize general performance and broad areas for improvement, it should rely on high-level diagnostics that address some of the major components of innovation, such as overall performance against goals and staff identification of perceived problem areas. If the management team is looking for specific targets for every aspect of the innovation process (for example, ideation, idea evaluation tools, selection parameters, team interactions, project management, and effectiveness of the strategy), it should rely on detailed diagnostics targeted to these objectives. Table 10.1 includes some typical diagnostic areas.11

Table 10.1. Diagnostics Strategy

Because the innovation culture of a company is such an important part of the business mentality, leadership sometimes includes an assessment of the Innovation Climate to determine employees’ perception of how well innovation is ingrained in the business mentality. Understanding the perceptions of innovation across the organization and the cultural norms associated with innovation can be critical to understanding the obstacles to innovation. Typically, an Innovation Climate survey diagnostic is used across and through all levels of the organization.

One leading consumer goods company used an Innovation Climate diagnostic to understand how well innovation was ingrained in its business mentality. The leadership team had already launched a diagnostic regarding the adequacy of the innovation strategy, processes, resources, and organization. It had a wealth of information regarding each of those functions and had identified several areas that would benefit from improvement.

However, some in the leadership team wanted to dig a little deeper and understand the cultural health of innovation in the company. The past few years had seen instances of significant friction between the business and technology functions regarding what innovations were most important to the business. The leadership team wanted to understand what was behind that friction and ensure that the improvements it was about to undertake would not be undone because of some overlooked cultural issues. They fielded an Innovation Climate survey across the company, with a particular focus on the brand management and technology areas where the acidic conflicts had occurred.

The result of the Innovation Climate assessment was sobering. Most people in the company felt that, despite spending heavily on innovation and having good processes, resources, and strategy, senior management did not truly support innovation. As a result, people in the organization, especially the marketing department, had adopted the attitude that innovation was a nice-to-have element but was not crucial to the company’s survival. The technical community had developed a subculture that favored incremental changes to exiting products. The diagnostic demonstrated to the leadership team the power of culture; its portfolio of investments, clear innovation strategy, and strong innovation systems had not been enough to integrate innovation into the business mentality. Something was missing from the culture, and it stopped meaningful collaboration. The leadership team identified the missing elements—including stronger senior involvement in innovation decision making—and selected the priority areas that needed to change. The leaders launched an initiative to change the prevalent mentality, reestablish a culture of collaboration, and improve the Innovation Climate. In addition, they committed themselves to periodically reassessing the Innovation Climate to ensure that they were making sustained progress.

Figure 10.1 presents an example of an Innovation Climate survey. Applied across the company, the survey requires the respondent to identify two ratings for each of the identified elements:

• Company best practice for that element (what level should the company strive for)

• Actual company performance for that element

Figure 10.1. Innovation Climate diagnostic13

This information identifies important employee perspectives about what is desired in the company’s culture, as well as how well the company performs.

GE realized that, given CEO Immelt’s strong focus on innovation, the culture in GE needed to be changed. The training center in Crotonville, the bastion of culture management in GE, added five new leadership traits to the idealized GE job description: external focus, clear thinking, imagination, inclusive leadership, and confident expertise. These additions reflect GE’s recognition of the need to change its culture via training.

GE also realized that the company needed to pay particular attention to the balance between creativity and value capture. This critical balance allows the company to generate successful new ideas and gets the maximum return on investment. Under Jack Welch, GE had become proficient at operational execution but had lost some important parts of its ability to create new products. When he became CEO, Immelt saw that GE’s value capture and commercial execution had become stronger than its creativity. He had inherited a company that had become extremely skilled in operations. The company was “one that could stop on a dime and deliver results,” says Bob Corcoran, the current director of GE’s legendary learning center, Crotonville, and a long-standing human resources manager at GE Medical Systems, the business Immelt ran before becoming CEO. “Now the question is how to develop the top line (defined as new products, markets, and lines of business).”12 This imbalance threatened Immelt’s plans to aggressively grow GE via innovation, and he launched an initiative to reinvigorate the creativity functions and increase the rate of idea and deal flow.

Leadership teams looking at the balance of creativity and value capture need to look carefully at the project management systems used in the company. Four very different types of innovation management approaches exist—stage gate systems, venture capital models, technology innovation model, and time-driven systems—and each has its own creativity and value capture biases.

Stage Gate Systems

Incremental innovation projects often rely on some version of stage gate process (Figure 10.2 depicts a stage gate process), with the project divided into stages and a gate governing the transition from one stage to the next. The sequential stages have an embedded cause-and-effect structure in which the success in executing a particular stage is a prerequisite to moving to the next stage. The measurement model provides the information required to track the evolution of a project throughout the course of the stage gate process. Exxon has used a gate process since the 1980s, with great success. According to Exxon, it has been the best initiative the company has undertaken in a decade; it has shaped the way Exxon does business.

Figure 10.2. Stage gate systems and investment and ability to influence profiles

The project’s progress is put under the magnifying glass at each gate. The measurement system enables monitoring to ensure that the project stays on track and is likely to meet or exceed the original expectations. At Cintas, every deal, no matter how small, is periodically scrutinized by a dispassionate executive, according to former CEO and chairman Robert J. Kohlhepp. That executive must have no qualms about pulling the plug if a deal smells wrong.14 Alternately, continuing a project that will create a competitor to an existing business requires a dispassionate decision maker focused on the long-term success of the company. HP’s ex-CEO Lou Platt noted, “We have to be willing to cannibalize what we are doing today in order to ensure our leadership in the future. It is counter to human nature, but you have to kill your business while it is still working.”15

Properly implemented, stage gate systems tend to produce balanced creativity and value capture. The beginning of the process focuses on creativity and transitions seamlessly to value capture via commercialization. However, cultural biases against creativity often creep into the system. The result is an increase in the degree of scrutiny and rigor of analyses in the early part of the stage gate process. When that happens, creativity can be strangled because good ideas that do not have clear financial payback are considered less worthy and are discarded or treated as second-tier opportunities. However, some semiradical and radical ideas do not have clear markets identified, reliable cost estimates, or highly reliable financial projections at their inception. These potentially attractive ideas can be discarded in favor of incremental innovations that have clearer performance measures. When this happens, the stage gate system becomes very efficient at value capture and commercialization of incremental innovations, but it lacks sufficient quality and quantity of creative ideas because they were dropped in the early stages. This imbalance of creativity and value capture results in rampant incrementalism, one of the best indicators of an out-of-balance innovation system.

The Venture Capital Model

This model relies on a venture team to interpret the fuzzy measurement information and make decisions at each stage of the investment process. It is widely used to manage semiradical and radical innovations. The SpaceShipOne venture team working on commercial space flight made decisions even though there were no credible estimates of the market size or demographics for commercial space travel, and there were still major uncertainties in the technology and business model.

The venture team members bring together their experience and their instinct about the technology and market with the quality of people in the project and their progress. The role of the measures is to capture the most relevant aspect of the project to stimulate discussion. The richness of the interpretation of the information adds value.

In the very early stages, when the ambiguity and uncertainty are the highest, concrete milestones are important measures of success. Are the technology prototypes produced on schedule? Have the key elements of the business model been characterized and tested with key stakeholders?

In the later stages of development, the need to characterize the target market becomes greater. The measurement system focuses on identifying and characterizing the specific target segment that will drive the initial growth, the robustness of the technology to meet the needs, and the cost structure of the business model (customer acquisition costs, customer support costs, and manufacturing costs).

The venture model deals fairly well with creativity; it allows consideration of radical new ideas in all stages of development. It especially favors creative solutions in the early stages of development. In the later stages of development, it requires more rigorous analysis and uses financial measures to guide decisions. However, the venture model can be biased toward creativity; it lacks the rigor of value capture commercialization contained in the stage gate systems. It is often beneficial to blend a stage gate methodology into the later stages of the venture capital approach, to ensure the necessary balance between creativity and value capture.

The Technology Innovation Model

The technology innovation model describes radical innovation that is driven from the technology group within a company. Typically, the initial work is unstructured and relies on ensuring that technologists have time to spend on their own projects. 3M ensures that researchers have 15% free time to explore new ideas. Google and Genentech allots 20% for exploration.

The role of the measurement system in the early stages is limited; at most, it tracks inputs to the project, including time and expenses. The initial stages rely on the intrinsic motivation and ingenuity of the particular technologist or team of technologists and the vision of management. There is no significant planning at this stage; intangibles such as trust, reputation, and “believing in the team” become more important in keeping people focused and motivated. As the innovation comes into sharper focus through experimentation and prototyping, the measurement model becomes more sophisticated, paralleling the venture capital model previously described.

Time-Driven Systems

For many incremental innovation projects, the key phrase is “schedule driven”—no matter what the cost, the company must say, “We must meet schedule.” Time as a measure is popular because it is universally understood and simple to measure, with obvious results; a project is on time or it is not. Projects that fall short are usually cut or significantly changed. One major car company executive reported that, in his company, meeting the schedule was significantly more important than meeting budget. Typically, projects were always 60% to 70% over budget, but this was acceptable if there was no schedule slippage.

However appealing this simplicity is, time-based systems are inherently biased toward capturing value; they do not lead to optimum use of creativity. Time-based systems favor getting the job done fast and encourage the spread of rampant incrementalism. In addition, time-based measurements focus on outputs, not outcomes. To be truly effective, systems must incorporate all four types of measures: input, process, output, and outcome. Using time as the only measure may appear expedient, but it runs the risk of leading to bad decisions. All things considered, time-based systems are inherently unbalanced and should be avoided.

The leadership team needs to neutralize organizational antibodies that kill off good ideas because they are different from the norm. One leading energy company did not curtail the organizational antibodies during its initiative to improve innovation. The antibodies showed in several different forms. Middle managers who resisted the changes did not provide adequate staffing, and the innovation initiative was understaffed. In addition, several managers sent their second-string team members. The original project schedule was aggressive, signaling the importance and urgency of the initiative. However, schedule slippage occurred almost from the first day. In addition, managers often missed key meetings where important implementation decisions were made. All of these diminished the effectiveness of the initiative and signaled to the organization that there was significant resistance to the initiative. If that were not enough, some key players in the company began to naysay the effort, casting doubt on its effectiveness and value. All these antibodies could have been effectively countered if the senior management team had stepped forward, demanded that appropriate actions be taken, and squashed the bad behavior. Unfortunately, that did not occur, and the initiative failed.

Leadership should also ensure that the organization contains strong innovation networks inside and outside the organization. Networks, not individuals, are the basic building blocks of innovation. HP’s former CEO Carly Fiorina said, “We focus our innovation where we can make the unique contribution and lead at the high bar, and we partner the rest.”16 Coca-Cola established networks that stretched throughout the global enterprise and focused them on their innovation platforms. To be effective, the networks have to be populated with a mixture of different types of people: idea generators, project managers, big-picture people, technical experts, and business strategists. Leadership should assess the caliber of the people in the network and the way they collaborate. Before launching a major innovation initiative, one consumer goods company conducted a skills inventory of its innovation networks and compared it against the technical and business challenges it faced. In addition, it assessed the collaboration and degree of alignment among the people in the network. This provided them with a clear indication of the networks’ strengths and identified areas for improvement.

Finally, leadership should ensure that the company has the correct metrics and incentives to make innovation manageable and to produce the right behavior. CEMEX’s management team created a balanced scorecard to drive the company’s innovation teams toward the goals it set. Tetra Pak has made innovation a basic part of the company from its inception. It had never relied on measurement to help manage its innovations. However, Tetra Pak had evolved into a complex company with a broad portfolio of innovations. As a result, it recognized that it needed to add some additional incentives to help manage the innovation process and to prioritize its investments. The new metrics and incentives helped the company shorten time to market performance by more than 20%.

Several rules govern metrics and incentives:

• Understand the strategy and business model of innovation for your company, and build a measurement system for innovation that is tied to both.

• Know what you want to achieve with each measurement system at each level of the organization. There are three options: communicate the strategy and the underlying mental models, monitor performance, and learn.

• Tailor the innovation measurement system to match the mix of incremental, semiradical, and radical innovation.

• Ensure that the incentives provide the motivation to drive the innovation strategy.

ChevronTexaco recognized many years ago that metrics and incentives were crucial to innovation and change. It instituted a formal process (very similar to a stage gate process) for all projects and innovation activities. The process includes the requirement to establish clear metrics that are tailored to the specific project. ChevronTexaco trains all its employees on how to use the process, and it holds every team accountable for managing according to the metrics. Finally, the company uses the metrics to learn and improve its performance. This approach, coupled with strong, aligned incentives, has served it well throughout the years; ChevronTexaco considers it one of its strengths in execution.

Organizing Initiatives

Two basic types of innovation initiatives exist. Fine-tuning initiatives are designed to provide selective modest improvements. Many companies undertake fine-tuning exercises every one to three years to maintain the vitality of their innovation capabilities. Redirection/revitalization initiatives are more aggressive, and their scope includes significant changes to their innovation capabilities. They occur less frequently. Companies undertake these types of initiatives when the situation requires more drastic action.

Fine Tuning

Fine tuning focuses on improving selective portions of the innovation strategy, portfolio, processes, organization, and culture. Fine tuning occurs when innovation is working relatively well (for example, the gap between desired and actual performance is relatively small) but improvements are required to improve performance and enhance competitiveness. Boston Scientific undertakes periodic assessment of its innovation processes to identify targets for improvement. Southwest constantly tunes its innovation capabilities; this is part of its culture.

Redirection/Revitalization

Redirection/revitalization initiatives are focused on major improvements to broad sections of the innovation capability. Redirection or revitalization is required when the innovation systems and organization are not delivering the correct types of innovations to adequately support the business strategy (such as when the gap between the desired and actual performance is relatively large). CEMEX undertook this type of initiative when it wanted significantly higher growth rates from innovation. Around 2000, Toyota recognized the growing importance of innovation in the automobile industry. It launched its redirection/revitalization initiative to capture the high ground in the highly competitive auto industry.

Generating Innovation Value

Every senior management team knows the drill: Define a goal, identify the problem areas that limit attaining the goal, understand their root causes, develop a plan, send the signal to the company that this is important, and then work out the millions of little details that comprise execution. Innovation is the same. There’s nothing to it but the basic blocking and tackling that all management requires.

What has frustrated many CEOs is that once they have executed improvements to their innovation capabilities—whether fine tuning or redirection/revitalization—they don’t get the results they hoped for. Admittedly, sometimes companies blow the execution of innovation improvements, but this is usually because they fail to neutralize the organizational antibodies that always come out when change is underway. Remember the energy company we discussed earlier that failed to neutralize the antibodies.

Far more often, companies fail because they do not understand the causal linkages between the parts of innovation. They launch efforts to fix some element of innovation and do not address the root cause of the problem. A household products division of a leading consumer goods company tried to fix its poorly functioning innovation effort by increasing the collaboration between the R&D and marketing groups. The working relationship between those groups was rancorous and produced suboptimal results, but the real problem was that leadership had not clearly identified the innovation strategy and defined the roles of business model change and technology change for the division. Without that leadership, each group made its own interpretation of what was important and the relative priorities to be assigned. Another company improved training on innovation in the hopes that everyone would improve. However, it did not address one of the key elements that needed to be changed, the cultural bias in the company against semiradical and radical innovations. Through many years of leadership, the company’s culture had grown to favor the incremental instead of the semiradical. The company was brilliant at execution, but it killed off ideas that were anything but incremental. Training everybody about the tools for semiradical and radical innovation would never produce the results the CEO desired.

Companies have no silver bullet for innovation, no one formula or structure for innovation that will work for every organization. The seven Innovation Rules provide the basis for executing improved innovation that creates value and growth.