Chapter Two. Moving to the Upper Right

This chapter introduces a Positioning Map, which shows how breakthrough products are differentiated from the competition. The Upper Right quadrant of the map integrates the attributes of Style and Technology and adds a third dimension: Value. Each remaining quadrant contains products that emphasize only style, technology, or low cost. By integrating the attributes represented in the Upper Right, breakthrough products meet the needs, wants, and desires of customers, resulting in increased sales, profit, and brand equity.

Integrating Style and Technology

The last chapter presented four case studies as examples of how companies can develop successful products that differentiate themselves from their competition through style, technology, and added value. GE Healthcare’s Adventure Series, Jarden’s Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker, BodyMedia’s FIT System, and Starbucks demonstrate a range of products and services. Additional case studies are presented throughout the book. We call the successful integration of style and technology “moving to the Upper Right.” This integration results in the creation of breakthrough products that are perceived as having high value. Although technology- or style-driven products do have some value, it is limited—and so are their markets.

At this point, establishing the definition of style and technology is important. Although we realize that these terms mean many things and can be interpreted differently, we are using them in a specific way.

Style refers to the sensory elements that communicate the desired aesthetic and human factors of a product or service. The style of a product must respond to a consumer’s expectations. It also produces the identity of the product. Style is the measure of how well a product responds to the lifestyle of the people who are the core of the intended market. The look, feel, and sound are all attributes that fit into style. Ergonomic issues, including comfort, ease of use, and safety, must complement the aesthetics.

Technology refers to the core function that drives the product, the interaction of components that are required to use the product, and the methods and materials used to produce the product. The core functionality can be mechanical, electrical, electromechanical, chemical, digital, or any combination of these. Interaction with core technology can require merely one button or a complex set of buttons and screen or voice commands. The choice of materials and manufacturing must be appropriate to the projected cost, must fulfill the requirements of internal components, and must complement the style requirements of the product.

We define value in more detail in the next chapter. In essence, a product is deemed of value to a consumer if it offers a strong effect on lifestyle, enabling features, and meaningful ergonomics and interaction, resulting in a useful, usable, and desirable product.

Marketing, engineering, and industrial and interaction design are required to blend style and technology and produce products that will be perceived to be of value. The challenge is getting these groups to work in a cohesive way.

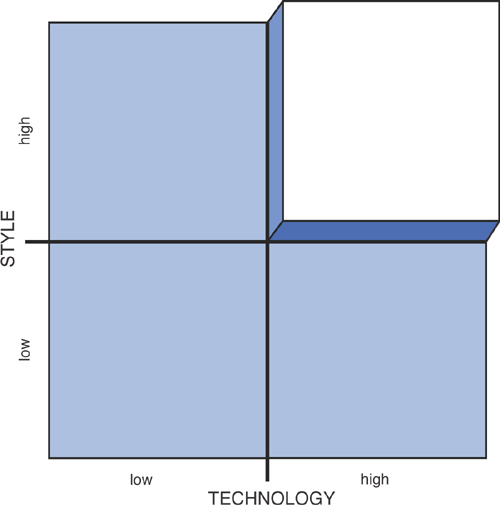

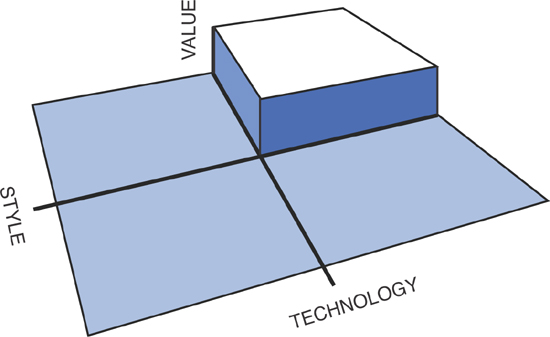

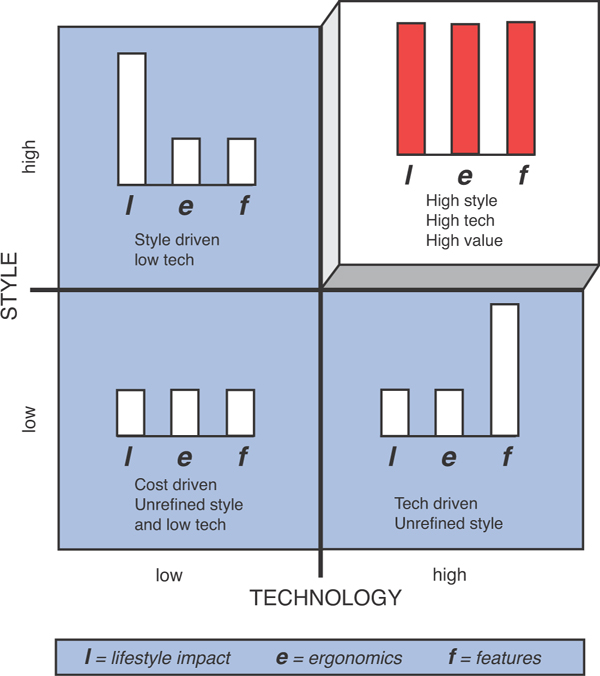

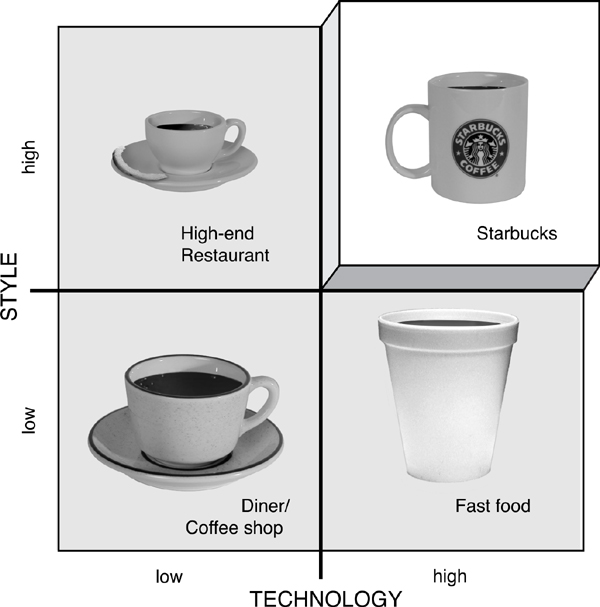

The Positioning Map shows how different products in the same category can be located in a matrix with Style and Technology as the two axes (see Figure 2.1). This map has a third dimension, Value (see Figure 2.2), which primarily exists in the Upper Right quadrant (and is only represented there), where companies make a concerted effort to integrate style and technology by responding to the needs of consumers. All of the companies that we highlight in this book realize that the playing field is three-dimensional. Although this approach can lead to increased cost in production, that cost can often be easily returned with interest by establishing a higher price for the product (along with higher margins), increased sales, increased interest in the company’s product lines, or established or reaffirmed brand recognition. People pay more for value and quality if they feel that a product connects to their goals and aspirations. Furthermore, products in the Upper Right have clearly recognized high levels of quality and value achieved through the appropriate articulation and integration of features and style.

Figure 2.1. Positioning Map of Style versus Technology.

Figure 2.2. 3-D Positioning Map—Value, the third axis found primarily in the Upper Right.

With the growing sophistication of consumer awareness, customers do not perceive products that lack an integration of style and technology to be valuable. For most of the twentieth century, value was defined as the most features for the lowest price—namely, value based on price, not value based on customers’ insight into what they value. The generic vegetable peeler pre-OXO is perhaps the symbol of this phenomenon. This view of value is changing. Although people are price sensitive in many of their purchases, certain purchases are driven by lifestyle compatibility. The higher the lifestyle compatibility, the less important price is in determining purchase. In the old era of mass marketing, purchasing tended to be consistent along taste and economic lines. In the new era of “demassification,” purchasing is highly variable. A person can live in low-rent housing but drive a Mercedes. Another person might own the most expensive climbing equipment and dress in only jeans and T-shirts. No one buys everything to match or project a certain lifestyle—but everyone buys something that does. Even after going through a down economy, people purchase what they value, even if what they value shifts.

Style Versus Technology: A Brief History of the Evolution of Style and Technology in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries

In this section, we provide a short overview of the evolution from the century of invention driven by technology, to the beginning of the consumer value-driven economy. A change in the SET Factors early in the twentieth century in Western Europe and after WWI in the United States created the beginning of market segments with different expectations, requiring the integration of style and technology.

In the Beginning

The historical integration of style and technology into products has been a slow and uneven process. The two primary factors that people valued were cost and emerging technology. During the late nineteenth century and most of the twentieth century, companies and inventors developed new products based primarily on technological innovations. For the period 1850–1950, handmade production methods were changed to mechanical and electromechanical ways of doing things. The challenge became making things that worked and that could be produced in large quantities at low prices, not making things that were beautiful to look at or even easy to use. Because these advances were new, the public had no way to compare products, and many people were eager to embrace the labor- and time-saving devices. The Arts and Crafts movement attempted to offset this trend. The emphasis on craft versus mass manufacture did little to stem the inexorable trend of invention and change over aesthetics and refinement. Aesthetics and human factors were always secondary or nonexistent in the development of products. The phrase “form follows function” was often used to an extreme to support the development of ugly, underdeveloped products that were only tech driven.

During the nineteenth century, mass-produced products and an industrial/service economy replaced the agrarian lifestyle and craft manufacture. Major milestones in this period include the development of Morse’s telegraph, the continental railroad system, Edison’s creation of an electrical distribution system, Eastman’s camera and celluloid film, Ford’s assembly line and the Model T, and the Wright brothers’ development of powered flight. Technology during the Industrial Revolution made products and services available to the emerging industrial urban middle class at an unprecedented rate. The camera, phonograph, refrigerator, VCR, computer, and microwave are all the results of product opportunities that stemmed from the major basic SET Factors that evolved in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Several factors made this possible: time (both the speed of doing things and the concept of free time), disposable income (the ability to have income or the ability to establish the credit to purchase things on time), increased literacy and other social reforms, and, finally, rapid advances in science and technology that created a plethora of new product opportunities.

The Growth of Consumer Culture

The technological advances of mass production met the growing appetite for mass consumption. As work hours decreased and wages increased, free time and excess income created the need for more products, services, and forms of entertainment. A variety of product opportunities emerged as office workers and homemakers looked for more efficient ways to work at the evolving speed of business and save time for more enjoyable activities in the home.1, 2 Many early versions of products resulting from new technological advances were ugly, crude, and dangerous. As the telephone became standard business equipment, telephone wires filled the streets of most cities; early powered farm equipment was extremely dangerous; early home appliances caused burns and electrical fires; and children were often hurt by exposed mechanisms, burnt by toasters and ovens, or shocked by outlets.

The word kluge was invented to describe underdeveloped technology-based products. The advantages these products provided in speed, power, and communication far outweighed the danger and visual clutter at first. Products were difficult to use, but, as Donald Norman has observed, humans often adapt to new products and blame themselves for their own ineptitude instead of blaming the manufacturer.3

This human trait of adaptation combined with a huge influx of cheap immigrant labor, the need for work at any cost in any condition, and the lack of unions and government standards to ensure reasonable working conditions.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, progress and change were more important than refinement and human factors. The developers of new technological products often neglected craft finish as a waste of time or rejected any hint of sophistication in favor of an extreme “form follows function” approach that could more accurately be described as form resulting from the limitations of manufacturing and the nonhuman elements of function. For instance, the early Model T was designed to be produced inexpensively, in a series of steps on an assembly line; little attention was paid to issues of ergonomics and style. As another example, an airplane propeller was designed strictly for the function of creating thrust and did not interact with human beings. For much of the early twentieth century, technology alone was enough to drive the development of products for consumer purchase. It took roughly a century for consumers to start to demand more from new products. As competition grew in consumer and certain industrial markets, companies started to use human factors and visual style as a way to differentiate their products from their competitors’ and give them a more up-to-date look. To create a major impact in an industry today, style and technology must be merged from the beginning. Products must change to respond to an ongoing set of factors that determine what customers expect. The tide is turning. While Norman’s observation was right for those raised in the Depression era and World War II, Baby Boomers and their children now expect products to conform to their needs, not the other way around.

The Introduction of Style to Mass Production

In the United States, the integration of style and technology did not occur until the mid- to late 1920s. American industrialists were inspired by the Decorative Arts Exposition in Paris in 1925 and wanted to bring that level of sophistication to American products. In 1926, Henry Ford was caught completely off guard by GM’s introduction of market segmentation and styling under the direction of Harley Earl. The Model T had dominated auto sales for 20 years, and Ford felt that it could continue for another 20. He did not see the product opportunity that the Roaring Twenties provided, but GM did. Earl brought style and color to GM cars. During the 1930s, trains were redesigned in the emerging streamlined style when railroad companies realized that the growing aviation industry posed a significant threat to their hold on public transportation (see Figure 2.3). Bus lines soon followed suit; the Greyhound bus company did a thorough overhaul of its vehicles in the 1940s. Manufacturers used large, bent sheet metal to cover appliances, to separate internal technology both visually and physically from consumers and their families. Companies put windows in washers and dryers to enable consumers to watch their machines do their work. Vacuum cleaners were made more efficient, lighter, and easier to move.

Figure 2.3. NY Central Hudson Locomotive, by Henry Dreyfuss, 1938.

(Reprinted with permission of Henry Dreyfuss Associates)

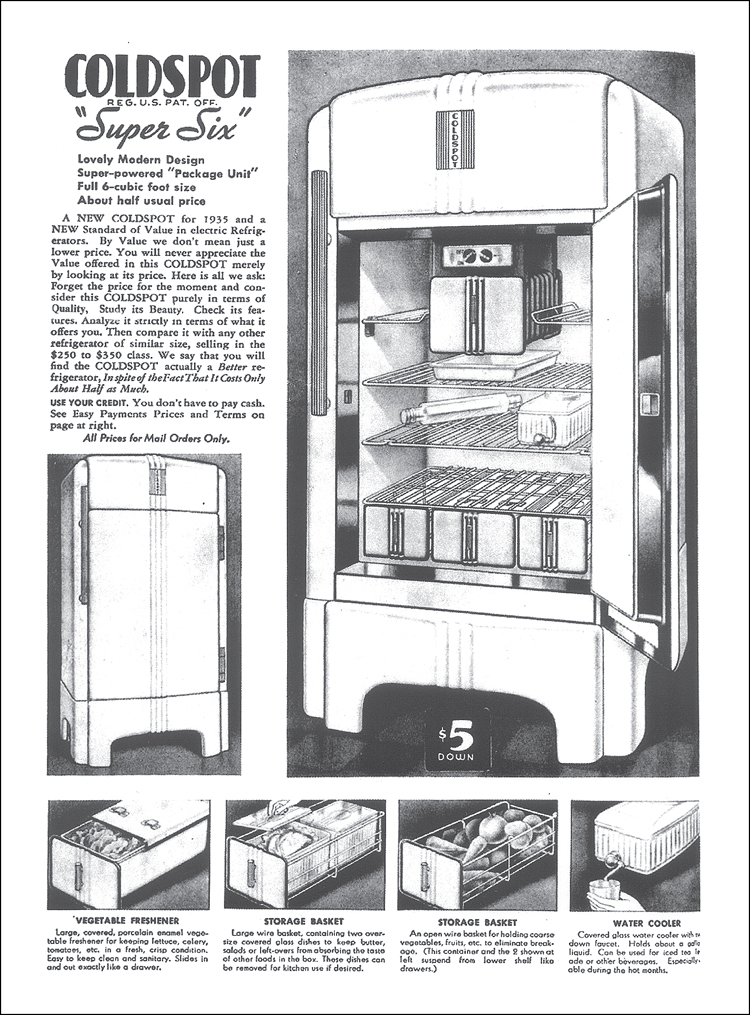

The 1935 Sears Coldspot Refrigerator (see Figure 2.4), developed with the input of designer Raymond Loewy, dramatically improved the style and function of the refrigerator. The product got a clean new look, and the cooling unit was covered with sheet metal. The doors were easy to open even when a person’s hands were full of groceries. The interior metal shelves were replaced with aluminum, to prevent rusting. The resulting dramatic increase of sales was an early example of success through the integration of style and technology. When the 1934 Coldspot was introduced, sales went from 65,000 units per year to 275,000.4 Even the advertisement for the Coldspot, shown in Figure 2.4, had a view of “value” that would emerge again as relevant today: “By Value we don’t mean just a lower price.... Forget the price for the moment and consider this Coldspot purely in terms of Quality. Study its Beauty. Check its features. Analyze it strictly in terms of what it offers you.....”

Figure 2.4. Sears Coldspot Refrigerator, by Raymond Loewy, 1934.

(Reprinted with permission of Loewy Design)

Other examples of the merger of style and technology at the time include the design of a new telephone for AT&T, aided by design consultant Henry Dreyfuss. The new design had an integrated, elegant new look and increased ergonomic comfort of the headset and base. It quickly became the standard for both the workplace and the home, as discussed further in Chapter 7, “Understanding the User’s Needs, Wants, and Desires” (and shown in Figure 7.10). The 1939 World’s Fair also celebrated the future of America as a land of prosperity with endless product options for the home and business.

Post–World War II Growth of the Middle Class and the Height of Mass Marketing

Initially, high-end products for the upper class were well designed, but products for the middle and lower classes were not. Not until after World War II did the merging of style and technology start to appear in products available to all economic levels. The United States’ involvement in the war resulted in American companies achieving maximum manufacturing capacity and fostered the development of new technologies. Three major examples were the computer, the jet engine, and the nuclear bomb. The combination of manufacturing capacity, the return of career- and family-oriented GIs, and the subsequent Baby Boom generated a tremendous market for new products. The design of cars in the 1950s reflected the exuberance of the era—cars sported fins of all types and sizes. This “supersonic” style, combined with eight-cylinder engines, mass production capability created by the retooling after World War II, and low gas prices, epitomized the integration of style and technology of the era. The cost of low-end cars became affordable to many more people. Buyers could identify a brand that connected to their lifestyle and could buy their way from Chevy to Cadillac or Ford Fairlane to Lincoln.

During the late 1950s and early ’60s, IBM and Westinghouse developed comprehensive brand identity programs that merged their state-of-the-art products with the emerging International style. Graphic identity, products, work environments, and architecture were all subjected to rigorous guidelines under the direction of external consultants Elliot Noyes and Paul Rand.

This post-war boom era lasted until the oil embargo of the 1970s. It was a time when mass manufacturing potential was met by mass consumption. Consumers behaved in consistent patterns of purchasing and could be grouped into large mass markets.

The Rise of Consumer Awareness and the End of Mass Marketing

By the 1970s, consumer patterns started to change. The age of consumer awareness evolved as Ralph Nader attacked the lack of safety and quality of American products. This type of product evaluation gave rise to a variety of consumer protection groups (such as state public interest research groups), publications (such as a modified Consumer Reports and Consumer’s Digest), and legislation (such as the Americans with Disabilities Act). Consumer groups started to split into smaller niches defined by age, geography, education, and income. This new consumer awareness led to the trend of demassification, or the breakup of 50th-percentile-based marketing into a smaller cluster of markets, which became known as niche marketing. A break occurred between the generation that had survived the Depression and World War II, and the Baby Boomers, who had only known prosperity and wanted peace at all costs. Civil rights, women’s rights, and environmentalism created entirely new types of consumers. They expected more from the products they bought and had both very particular demands and a new range of interests that exceeded their own personal needs, wants, and desires.

When IBM tried to transfer its business machine mainframe mentality and austere modern corporate identity to the design of personal home computers, it had trouble “crossing the chasm” from lead users to the early majority.5 Although the company’s use of a Charlie Chaplin imitator was the right image in commercials for the ordinary guy, its computer was not for the average person: IBM could not escape the cold design and poor interface of its business machines. The first Macintosh computer had a new look and interface that consumers responded to. Apple beat IBM in the emerging home computing era of the 1980s. The Mac was user friendly, and the product looked cute, not technological. The mouse was an easy-to-use peripheral product that added an additional friendly form to this new technology. Although the overall idea was developed at Xerox PARC, Steve Jobs was the one that saw the POG and acted on it. The software was easy to learn to use, allowing people to start up quickly and become functional users. The technology alone did not sell successfully to the mass public; the added usability and style, along with the technical capabilities, sold the computer. This feat was re-created when Jobs rejoined Apple and saved the company by introducing the iMac—it succeeded for exactly the same reason that the first Mac did. The success of the iPod, iPhone, and iPad followed the same approach: Technology alone was not enough.

Technology alone did not sell the Mac, iPod, iPhone, and iPad to the masses. The added usability and style sold the devices.

The same was true in other industries as well. The U.S. auto industry was caught completely off guard by the oil embargo of the 1970s, allowing Japan to take over the U.S. small car market with low-cost, fuel-efficient, and eventually near zero-defect cars. People’s needs, wants, and desires had changed. However, the U.S. auto industry hadn’t recognized the need for change. Xerox lost its once-dominant control of the copier industry by failing to recognize that consumers wanted copiers that were more reliable. Xerox had been able to get incomplete technology into the market by backing it with excellent service. Japanese companies saw this gap and filled it with copiers that did not need service and looked better in the office environment.

The Era of Customer Value, Mass Customization, and the Global Economy

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the concept of product development has changed in all markets at all economic levels. Companies are now competing globally in more diverse and demanding markets. In the current global market, a small, previously unknown Finnish company (Nokia) can effectively compete against a giant (Motorola) in the design of cellular phones. Consumers today no longer behave in large, predictable groups. They do not follow simple, consistent patterns of purchasing. With the iPhone, Apple introduced a highly successful approach to mass customization. Through the millions of apps available, every customer can create a unique product, not through different physical products, but by creating individualized functionality by choosing a particular selection of apps.

We are now in the era of information, with segmented markets and consumers that can research and buy their products through a number of media channels. The access to cultural patterns of change is higher than it has ever been. Almost everyone in industrial nations can watch television, see movies, surf the Web, read magazines and newspapers, and listen to the radio. Many people do a number of these things simultaneously.

All consumers are searching for a sense of integrity and their own version of value and quality that can help them fulfill their lives. Today’s consumers have a much clearer sense of their own identity and who they want to connect with (market segment), and they are also well aware of the range of products available. Customers are looking for products that are well made, that are safe, and that match their lifestyle. Everyone has a number of product categories, where they expect a product to make a statement about who they are and how they want to live their lives.

Products can no longer simply provide a service, nor does simply styling a product work. Integrating style and technology through features is the only way to be competitive and maintain a customer’s loyalty. Moving to the Upper Right means committing to style, technology, and value.

Positioning Map: Style Versus Technology

We can compare how products differ in their use of style versus technology by placing them on a Positioning Map, as shown in Figure 2.1. The four quadrants represent differences in the amount of style and technology that is designed into the product. The Upper Right quadrant is the one to be in if your goal is to be a leader in the marketplace and you want to maximize your profit. The products in the Upper Right exhibit an integrated approach with a balance of both style and technology. In the Upper Right, balance is achieved through the use of the third axis: understanding the value systems of the intended market (see Figure 2.2). These products maximize lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics. The third axis, value, is not integrated into the products placed in the other three quadrants. Note that, in the 2-D version of the map shown in Figure 2.1, the Upper Right is separated from the rest of the map. We do this to emphasize the third dimension of value in that quadrant. We now examine each of these quadrants in more detail.

Lower Left: Low Use of Style and Technology

Products in this quadrant are typically generic, designed with established technologies and minimal styling. As shown in Figure 2.5, they have minimal lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics. These unrefined products sell to consumers who do not seek out value but instead are driven primarily by low price: functionalism at low cost. These products might have been innovative early in their existence, but they have failed to respond to change and have become obsolete on a number of levels. Products in this quadrant establish the baseline of the product category. They are usually manufacturing and materially driven—that is, they rely on minimal use of material, quick cycle time, and minimal assembly time, and they keep a low cost per unit to make a profit. These products have few, if any, distinguishing features to differentiate them from other similar products. This approach was the classic for mass production and mass marketing and is still an approach that can work for commodities that have little value potential. Their undistinguished, low-cost design demands a minimal price, resulting in low profit per item produced.

Figure 2.5. Positioning Map indicating effectiveness in lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics.

A generic potato peeler, paper clips, a blender, the standard first-class business letter delivered by the U.S. Postal Service, and a cup of coffee in a coffee shop are all examples of generic products. In this quadrant, companies and customers seek value in the mass marketing sense. The product is made as cheaply as possible and distributed as widely as possible. Profit is made by high volume and low profit margin per item.

Lower Right: Low Use of Style, High Use of Technology

Products in this quadrant are driven by technology, with an expectation of sales based only on the added technological advantage or originality of the product. They maximize features but almost ignore lifestyle effects and, generally, ergonomics (see Figure 2.5). These products are often the first of their type and thus offer technological advance as their major competitive advantage. These products also work well in professional applications where style and ergonomics are not as important from a competitive standpoint. The same is true for military applications, even though attention to ergonomics might be more salient. Both cases, however, require a skilled user who is willing to overlook ease of use for performance. Profit in this quadrant is based on technological innovation, and the primary market is lead users and early adopters. They are willing to pay a premium to be the first with the new technology. However, this profit margin and early success does not continue past these aggressive segments. As Geoffrey Moore states in Crossing the Chasm,5 the early success of lead users is a false positive that does not translate to more conservative consumers who are interested in ergonomics and style. Although these products can achieve greater profit margins than those in the Lower Left, they usually have a limited market growth and must move to the Upper Right if they want to compete in consumer markets.

Manufacturing equipment, business-oriented computers and peripherals, and professional-quality service products all succeed in the Lower Right. Hewlett-Packard has been one of the most successful companies operating in the Lower Right. Their testing equipment, medical equipment, and plotters were standards in the professional markets. However, to compete in consumer markets, they have had to move to the Upper Right. The Windows operating system is far less user friendly than the Mac OS. However, Windows dominates through its position as the primary software for the Wintel PC and the one most used in business. As such, the PC, still in the Lower Right, is a product driven by more features for less money than the higher-cost, more usable alternative. High-end manufacturing tools typically find themselves in the Lower Right, with the expectation that customers care only about their performance. The Beyond Blast technology by Kennametal, discussed in Chapter 9, “Case Studies: The Power of the Upper Right,” illustrates the opportunity for such technology-based tooling to move to the Upper Right.

Upper Left: High Use of Style, Low Use of Technology

Products in this quadrant are driven only by style. Their products have high profit margin but limited market potential of total sales. Some companies that live in this quadrant explore the boundary of aesthetic experimentation (lifestyle impact) and usually fail in the application of human factors (ergonomics) and core technology (features)—see Figure 2.5. Examples include Alessi products from Italy, which often end up as decorative elements in high-end kitchens or offices. Some designers such as Philippe Stark develop products that push the boundaries of form, material, and tactile experience. Designers often look to these progressive ideas as a point of departure for future designs that can flow back into other, more complex and mainstream products. Profit in this quadrant is the result of either a market seeking out image and art or a company tricking consumers into believing that the highly styled look of these products is backed by competent ergonomic and technology design. This cosmetic approach usually fails for the opposite reasons that a high-tech product fails. Consumers quickly realize that these products are a compromise and that they rarely perform as anticipated. These companies are often looking for niche markets willing to sacrifice usability for expression alone.

Upper Right: High Use of Style and Technology

The Upper Right quadrant contains products that integrate style and technology and add the final factor that makes them successful: value. Here lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics or general interaction come together to enable personal expression, cutting-edge capabilities, and usability (see Figure 2.5). This combination allows products to differentiate themselves from the competition and define the state of the art for their market. How to successfully move to the Upper Right is the focus of this book. We have already discussed examples of breakthrough products in the Upper Right in Chapter 1, “What Drives New Product Development,” including the BodyMedia FIT System, the Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker, the GE Healthcare Adventure Series MRI, and Starbucks. Sometimes these products and services cost more to design and produce than those in the other quadrants, but consumers are willing to pay a premium for them. At other times, the resourceful and meticulous effort it takes to create an Upper Right product allows for a more efficient use of materials, technology, and manufacturing processes, resulting in a higher-profit product that costs no more to produce. Producing such an Upper Right product might even cost less because it includes only the features that people want, with no wasted technology (and its costs).

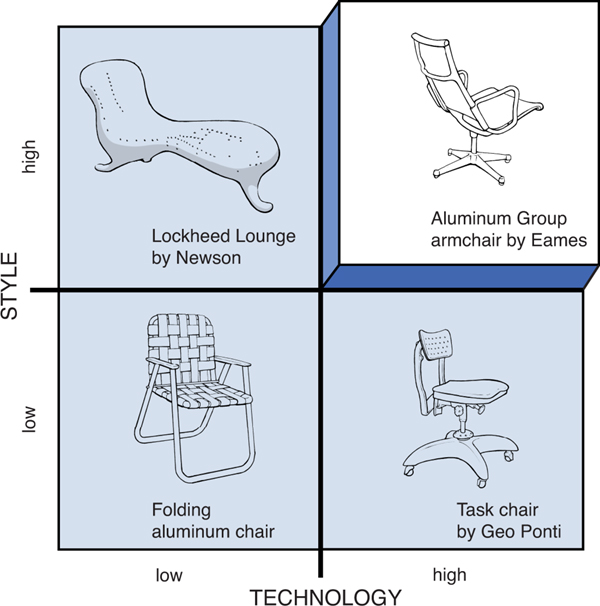

The goal is for new products to move to the Upper Right, or end up with a product in the Upper Right quadrant, as shown in Figure 2.6. Mapping your products and your competitors on the Positioning Map enables you to understand the scope of your competition and also how to differentiate yourselves from that field. You can then use that understanding to plan a strategy to move to the Upper Right. The process is not as simple as merely putting together an industrial designer and an engineer. The process is deep and intricate. We devote the remainder of this book to understanding the way products in the Upper Right differentiate themselves from the rest of the field.

Figure 2.6. Moving to the Upper Right.

Figure 2.7. Positioning Map of aluminum seating.

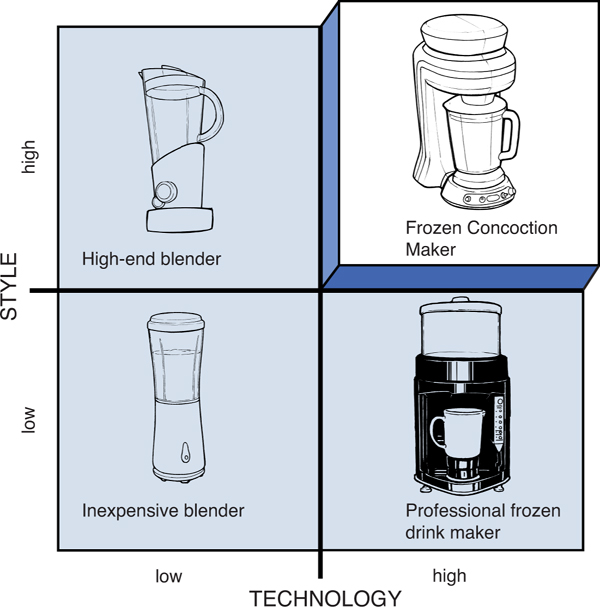

Positioning Map of Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker

The Positioning Map for the Frozen Concoction Maker (see Figure 2.8) shows the Upper Right opportunity for and delivery of the product. In the Lower Left is the standard blender that crushes (or melts) the ice but does not blend it into a smoothie. In the Lower Right is the high-end ultra-expensive professional mixer used in bars and restaurants. The Upper Left includes a stylized version of the blender, not different in performance than its Lower Left cousin. The Upper Right is where the Frozen Concoction Maker and high value lie, a combination of technology that mimics the performance of the high-end mixer, but at a fraction of the cost and with the lifestyle component to excite the target market of Baby Boomers, the broader market of Jimmy Buffett fans and wannabes, and frozen margarita fans alike.

Figure 2.8. Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker Positioning Map.

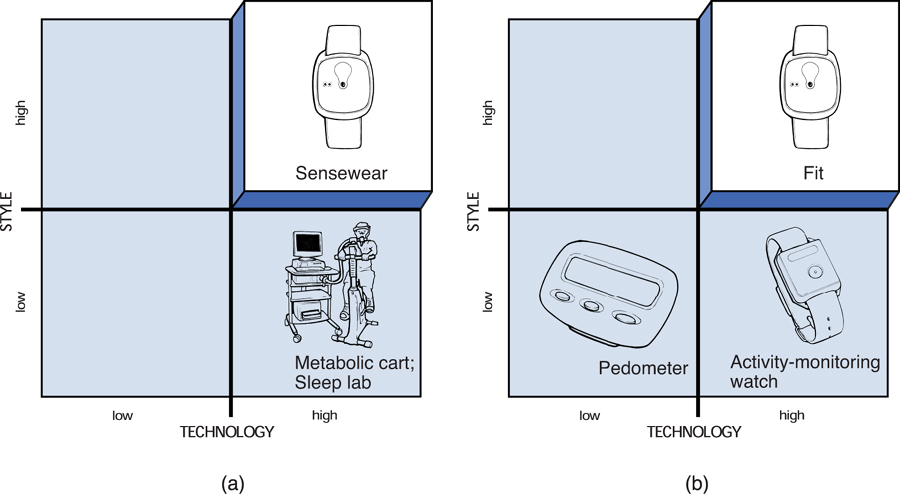

Positioning Map of BodyMedia FIT System

BodyMedia has two Positioning Maps, one for the clinical SenseWear System (see Figure 2.9a) and the other for the consumer FIT System (see Figure 2.9b). When the company started and introduced the SenseWear System to the clinical market, the only competitors were the low-style, high-technology medical devices; the polysomnography (sleep lab) and VO2 (the metabolic cart). As already described, these clinical systems are cumbersome, requiring leads attached to the skin and tubes for the mouth. Furthermore, they require the patient to be in a lab instead of in their home or out doing activities. No attention to style is given; these are function-driven systems. In the medical field, no high-style products without function exist. In the Lower Left, generic products emerge only for very mature technologies that did not yet exist in this clinical domain (although the sleep lab and metabolic cart technologies were already routine). The SenseWear System was uniquely positioned in the Upper Right, adding value to the user through ergonomics and style integrated with new technology for mobile and comfortable multisensing capabilities.

Figure 2.9. Positioning Maps for the clinical SenseWear System (a) and consumer BodyMedia FIT System (b).

When the company decided to introduce a product in the consumer market, the Positioning Map looked totally different. In the consumer world, no high-value competitors existed. In the Lower Left were a selection of pedometers, able to provide information only on the number of steps a person had taken. Some of these were quite generic; at one point, McDonald’s introduced an adult Happy Meal with a “toy” pedometer. Others of these were higher tech but still limited in providing information only on steps taken. In the Lower Right was the activity-monitoring watch, which, at the time, was a clearly clinical product that attempted to chart activity monitoring, but using only an accelerometer. Again, because people were interested only in products that delivered meaningful information, no high-style but low-technology competitors existed (except for any pedometers that attempted to add a level of color or a better interface). The BodyMedia FIT System brought style and technology together into a high-value product, not only through the physical device but through the service that analyzed the data and provided guidance on how to improve weight loss.

In some ways, the success of the FIT System in the consumer market is similar to the success of the iPod for Apple. Because Apple could integrate MP3 technology with the iTunes service, making the transfer of songs easy and the purchase of new music even easier, the iPod device coupled with the iTunes service reached the consumer market and redefined the music industry. In the case of BodyMedia, the technology was state-of-the-art. But because the service allowed the company to control the data, it could process it and provide the feedback that consumers sought, without them needing to put in the effort to do so. BodyMedia brought the technology to the background, allowing nontechnical users to participate.

More than a decade later, BodyMedia is still the leader, having pioneered the space of technology-based self-care. Competitors exist and continue to try to match the capabilities of the FIT System. However, because BodyMedia has multiple international utility and design patents, name recognition, and a technological know-how advantage, competitors have found it difficult to move into the space defined by BodyMedia. One aspect of these patents includes the use of multiple sensors to assess physiological well-being, generally designating competitors to settle with only one sensor and, thus, limited information. Design patents also protect their aesthetic, which has defined the industry (and the brand, as seen on The Biggest Loser). The company actively enforces its intellectual property (IP), enabling it to retain its position in the Upper Right of value.

Positioning Map of Starbucks

Our arguments can also be applied to Starbucks, a service-based company (see Figure 2.10). Before Starbucks, the most popular group meeting place was a coffee shop or diner (Lower Left). People met for business, discussion, and, of course, coffee. Minimal service and customer turnover meant profit (low profit per person but high volume); the idea of hanging out with a laptop and sipping a cup of Java was an opportunity that most people did not see. For people seeking out the quick and reliable cup of coffee, Lower Right fast food restaurants had the technology to deliver a consistent, though not necessarily enjoyable, brew in a (usually) stark atmosphere. Upper-end restaurants (in the Upper Left) provided an inviting atmosphere but without a guaranteed consistent brewing quality.

Figure 2.10. Starbucks Positioning Map.

Starbucks introduced and brought into the American mainstream the concept of a European cafe integrated with a West Coast contemporary look and feel. Starbucks, clearly in the Upper Right, combines technology through roasting and brewing with style through the upscale retail environment. Starbucks’ first store opened in 1971. Not until 1984 did Starbucks open its second store in Seattle. By 1999, the company had grown to 2,500 stores in more than 13 countries; by 2010, it had nearly 17,000 stores in nearly 50 countries across the globe. As discussed in Chapter 1, the Starbucks line has extended into supermarkets, other products such as ice cream, and peripherals for coffee and tea drinkers. The Starbucks chain gave rise to a host of national and local copies. Some are poor copies; others have attempted to move to the Upper Right by offering a different but still high-quality product. Bookstores have installed coffee shops to heighten the book-buying and browsing experience and to make them more like libraries combined with coffeehouses—a notable example is Barnes & Nobles, which partners with Starbucks.

Positioning Map of GE Adventure Series

The GE Adventure Series is a different type of example of moving to the Upper Right. The Adventure Series is not about developing new technology: The product is the exact same technology as any other GE CT scan device. It is also not about changing the form from the original machine: No new parts needed to be molded. Instead, it is an example of interface design and the capability to transform a product through the means by which the form and technology are delivered, to address the empathetic and emotional needs of the user (in this case, the child patient). The Positioning Map is simply the traditional CT scanner in the Lower Right and the Adventure Series in the Upper Right (see Figure 2.11).

Figure 2.11. GE Adventure Series Positioning Map.

(Courtesy of GE Healthcare)

Knockoffs and Rip-offs

As already indicated, when a product succeeds in the Upper Right, it often inspires a multitude of companies looking to copy its success without the investment in the value represented through lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics. Companies take one of three directions. Established value-oriented companies cannot just copy, for fear of blurring their brand. These companies are forced to develop different Upper Right solutions that have equal perceived value. In this case, the Upper Right product spawns new Upper Right products designed for a different insight. Many companies, however, have the goal of competing by charging less and skimming the profits of the original Upper Right product, thus appealing to customers who believe they can get the same value for less cost. These companies configure themselves to actually copy. They want to take advantage of the brand identity of the leading company. Unless a product can differentiate itself from one in the Upper Right, it will end up back in the Lower Left or off the map altogether. Companies driven toward a lower price point but able to create a genuine product end up in the Lower Left. Most times, however, companies interested in ripping off success use a cosmetic approach but sacrifice on choice of material and manufacturing quality. The product is neither technology nor style driven and lacks the sincerity of a generic product. This pushes the product off the map altogether. Consumers quickly realize that these products are a compromise and that they rarely perform as anticipated. The companies that do this are usually positioned for sales in lower-end retail stores and are often looking for short profit cycles with no investment in brand loyalty.

Many companies have been trying to rip off the look of GoodGrips products (see Figure 2.12); all of them are cheaper in price, but none works as well. However, the clear difference in quality and the consistent innovation that stems from the company continues to place its products in the Upper Right.

Figure 2.12. Selection of GoodGrips knockoffs.

In contrast, in the first edition of the book, we featured the Black & Decker Snakelight (see Chapter 11, “Where Are They Now?”). The Snakelight is a clever hands-free flashlight with a flexible core that can wrap around a person’s neck or be positioned to sit on a surface for hands-free lighting. The Snakelight had a successful ride as a high-valued Upper Right product. However, cheap knockoffs made of inferior materials and lower-quality manufacturing lessened its perceived value. Because the company did not continue to innovate and differentiate the product, it soon became commoditized.

The compromise of quality in materials and craftsmanship of rip-off products results in poor performance and short product life. These rip-off, low-cost companies are often sued successfully for design and utility patent infringements, costing the manufacturer far more in the long run than if it had tried to innovate in the first place.

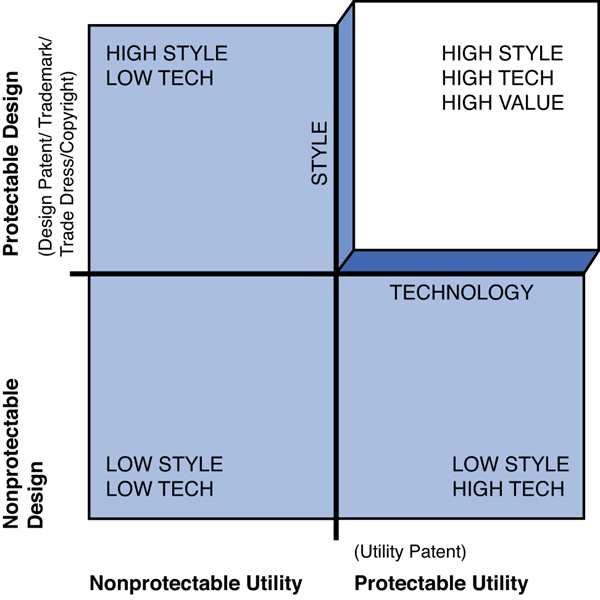

The Upper Right and Intellectual Property

Given the effort to develop a differentiating, breakthrough, high-valued product, the company has an interest in protecting the investment and preventing others from copying it. When most people think about IP protection, they think about utility patents that protect the functionality and manufacture of a product. However, a selection of IP tools protects innovation in both the technology and style of a product. Our book The Design of Things to Come6 offers a tutorial of the different types of IP tools. Figure 2.13 illustrates how IP law can protect all aspects of the breakthrough innovation. High technology is protected through utility patents. But style is protected through design patents, trade dress, trademarks, and copyrights. If a company uses all of these tools, the Sheer Cliff of Value to the Upper Right can be difficult, if not impossible, for others to climb.

Figure 2.13. Positioning Map showing different ways to protect a product through IP tools.

Revolutionary Versus Evolutionary Product Development

Upper Right products can be revolutionary new products or evolutionary changes to an existing product line. Revolutionary products establish a new market or solution within a market. Evolutionary products typically begin in the Upper Right and remain there as new useful, usable, or desirable innovations that address the dynamic SET trends. They require injections of new value to maintain the consumer’s connection to the product. Revolutionary products enter in the Upper Right and remain there only by becoming evolutionary products that change with the SET Factors.

Figure 2.14a shows the perceived innovation of a product in a market and how a company introduces revolutionary changes to maintain the perception of cutting-edge innovation and capture new portions of the market. As an example in the figure, Apple introduced revolutionary innovations in its products, beginning with the iMac (and the original Mac before it), then the iBook, and next the iPod, iPhone, and iPad. To keep the product in the Upper Right, new models must add innovations that meet the needs, wants, and desires of the market. Figure 2.14b shows how these injections of innovation keep the product line at its peak in the Upper Right. For this example, for the Mac, each successive product increased computation capabilities while compacting the components into smaller forms that could be integrated into varied cutting-edge form factors. Each of these innovations kept the company ahead of the competition and in the Upper Right.

Figure 2.14. Revolutionary new Upper Right products (a) and evolutionary maintenance of an Upper Right product (b).

The goal, then, is to become and remain a leader in the Upper Right by introducing revolutionary new products or evolutionary changes to existing products. To do so, the product must add significant value over the competition. Understanding value, not just trying to copy successful examples in the market, is critical to the success of the move to the Upper Right and is the focus of the next chapter.

Summary Points

• Throughout history, breakthrough products have succeeded by merging style and technology.

• Breakthrough products are found in the Upper Right of a Positioning Map, indicating high style, high technology, and high value.

• Breakthrough products in the Upper Right maximize lifestyle impact, features, and ergonomics.

• Upper Right products lead or create new markets.

• Both evolutionary and revolutionary Upper Right products demand constant innovation.

References

1. A. Marcus and H. Segal, Technology in America: A Brief History (Florence, KY: HBJ College & School Division, 1999).

2. G. Porter, The Rise of Big Business: 1860–1920 (Arlington Heights, IL: Harlan Davidson, 1992).

3. D. A. Norman, The Design of Everyday Things (New York: Currency/Doubleday, 1990).

4. R. Loewy, Industrial Design (Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 1979).

5. G. Moore, Crossing the Chasm (New York: Harper Perennial, 1999).

6. C. M. Vogel, J. Cagan, and P. B. H. Boatwright, The Design of Things to Come (Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005).