Chapter Seven. Understanding the User’s Needs, Wants, and Desires

To create a breakthrough product, your company must know who your customer is and how to place that knowledge in the perspective of the market your product competes in. This chapter provides techniques to help you balance qualitative methods for understanding needs, wants, and desires with more quantitative approaches for assessing issues of usability. Traditional methods of ergonomics research are complemented by a range of other techniques, which include new product ethnography, scenario development, storytelling, task analysis, and lifestyle reference. The results of this research provide insights that characterize potential customers in the target market and serve as a basis for testing the validity of product concepts.

Overview: Usability and Desirability

According to the Human Factors Ergonomics Society (HFES), the discipline of human factors focuses on “the scientific ... understanding of interactions among humans and other elements of a system, and the profession that applies theory, principles, data, and other methods to design in order to optimize human well-being and overall system performance.”1 What is often thought of as a focused approach in biomechanics and anthropometrics is actually a much broader understanding of who and what a person is. As you learn in this section, many other members of the product development team, beyond human factors specialists, are interested in the characteristics of human beings and their relationship to systems and devices.

The HFES evolved from the systems analysis conducted by the military during World War II. The three main types of research were anthropometrics, interpretation and management of complex information, and systems analysis in the deployment of troops and equipment. The systems analysis varied in scale and complexity, ranging from the large-scale systems planning used in preparing the invasion of Normandy, to the process of understanding how to best place and equip personnel from an aptitude and size point of view. The D-Day invasion was one of the most complex events of the twentieth century. It required a scale of logistical organization of men and material that was unknown before the beginning of the war. On a smaller scale, the range of equipment and military assignments meant understanding how to organize, train, and assign military personnel to make the most of their aptitude and body type. Soldiers had to be trained quickly and effectively to use and maintain the vast array of war technology developed during World War II. There were size limitations for pilots, submariners, and tank drivers. The development of complex new equipment required finding the best personnel with the right training for navigators, cryptographers, code breakers, radar and sonar operators, and bomber pilots and crew.

After the war, as post-war companies and the products they produced grew in size, scope, and complexity, many of the systems analysts found opportunities in the commercial sector. This post-war focus gave rise to the formation of HFES in 1957, but the early origins of human factors can be traced back to the development of mass production and the need to improve efficiency in production. As the nature of work shifted away from craft production and agrarian labor, new concepts for working in factories evolved. The Ford assembly line and Taylor’s theories of efficiency2 started to have an effect on the planning process for the nature of work and education, and even in home economics, where women were instructed to organize and plan their homes around modern principles of domestic management. At the end of the twentieth century, a much broader concept of human factors was emerging—and evolving through to today. This new version is in response to the recognized need for a deeper insight into customers’ patterns of behavior. It involves qualitative research methods and explores emotional as well as cognitive issues in human factors. The HFES has a variety of technical groups, including aging, cognitive engineering and decision making, environmental design, individual differences, industrial ergonomics, medical systems and rehab, macroergonomics, safety, and visual performance. Currently, however, most research in the discipline of human factors focuses on usability, not on desire.

A successful brand creates a Gestalt image in the market, formed from a variety of factors, which include the look and features of the product, the name, the advertising, the price, and the perceived value to the customer.

A number of new trends are changing the way companies attempt to know their customers and their needs, wants, and desires. Many companies are using ethnography as a research tool in the early stages of product development. Ethnographic techniques are qualitative processes that apply methods from cultural anthropology to the field of product research. These techniques are proving to be valuable in early phases of marketing and in helping product teams develop the actionable insights they need to translate into the style and features that people are looking for. A second reason this is changing is the result of the new focus on brand management. As discussed in Chapter 4, “The Core of a Successful Brand Strategy: Breakthrough Products and Services,” many companies realize that giving a product a strong brand identity is a clear competitive advantage. The book Marketing Aesthetics, by Schmitt and Simonson,3 describes the value of a visual identity system and how all aspects of a product must communicate clearly and consistently with customers. A successful brand creates a Gestalt image in the market, formed from a variety of factors, which include the look and features of the product, the name, the advertising, the price, and the perceived value to the customer. By taking a broader view of what it means to factor the characterization of humans, this new category of human factors explores how a company’s core values can connect with the lifestyle goals of its customers. Harley-Davidson has created one of the most powerful brand identities in the world, merging the logo, core product (motorcycle), and complementary lifestyle products (clothing and gear) with the way customers want to live their lives. Even the noise a Harley makes is part of the brand.

Another reason the study of human factors is changing is a result of the emergence of interaction design. Interaction design, discussed further in Chapter 8, “Service Innovation: Breakthrough Innovation on the Product–Service Ecosystem Continuum,” is a vibrant area in human factors research and is based on human–computer interaction (HCI). This group recognizes the need to create more humane interactive products that cross hardware and software boundaries. It is also clear that quantitative research alone is not enough to solve these problems. Ethnographic research has become a part of HCI research so that researchers can better understand how people use and need computing in work and play (and how computers are integrating work and play).

The human factors discipline consists primarily of professionals and faculty from the fields of systems engineering, physiology, and cognitive psychology, but both the origins and current manifestations of the field are far broader. For nearly a century, advertising, marketing, industrial design, communication design, architecture, and the entertainment industry have all used a variation of human factors to help to define the parameters and evaluate the success of their products. Although these other fields might have lacked the formal research and forum for disseminating their methods through academic journals, recently their methods for abstracting behavioral models and customers’ likes and dislikes have found important relevance in industry and research. The emerging view of human factors is the need to develop qualitative, empathic methods to compliment the quantitative, logical methods that evolved in the twentieth century. The terms empathic and affective design and interaction have emerged to capture the need to convey emotion responses through product interaction by those in the field.

Because of new research and diagnostic apparatus in kinesiology and biomechanics, it is now possible to follow the mechanics of swing in sports, record the pressure of each finger on a keyboard, and track the eye movements of someone in a purchasing environment looking at competitive products. It is even possible to know what parts of the brain are involved in making a decision or observation through recent advances in the field of neuroscience and the use of fMRI machines.

The book Buyology, by Martin Lindstrom,4 summarizes emerging ways that marketers are uncovering consumer preference through such brain scans. New research is also beginning to uncover how product designs can account for preference from fMRI scans; for example, people clearly account for emotional decisions, not just rational decisions, when making choices of different product options, even when functional performance is a critical component.5

The SET Factors have changed and the pace of industry has accelerated, yet markets have become “demassified.” Product development has moved from a period of mass manufacture and consumption to a period that can be defined not only as mass customization, but also as mass customer-zation. Mass customer-zation is the act of attempting to understand the needs, wants, and desires of ever-smaller and rapidly changing markets. Mass customer-zation is also the ability to customize your order as you make the purchase or the support to customize your product or service after purchase. Mass customization is the product that results from that understanding. Too often companies try to customize before knowing the true needs of their customers. Every category of products now demands the use of a variety of research methods to gain insight into the way people live and work and what their desires are. The Pontiac Aztec is a now-classic example of a product that attempted to capture the X generation with a car customized to their every need. Yet it failed to hit the market the way the Nissan Xterra did several years before because, although it incorporated style and technology, it did not properly respond to the Value Opportunity attributes of pinpointing time and sense of place. Even in fields as seemingly conservative as manufacturers of lift equipment, the ability to add a sense of pleasure and pride in the design can be a major factor in determining success. The Crown Wave meets all the safety and anthropometric requirements for lift equipment. However, the style and name also make it viewed as enjoyable to use and create a positive incentive for people to come to work. The enjoyment factor is another type of broader view of human factors. We describe a number of methods in this chapter for helping you to understand your customer. The method of task analysis is a more commonly accepted method used by human factors experts, but scenario development is not. Scenarios are as essential as any other facet of early product development. The scenario gives a product development team a common and concrete vision of who the customer is. It translates the generic term customer into a person (or persons) with a name and personality attributes, and places that person in the context of where the product will be used.

In characterizing the inherent difference in philosophy and approach between the two main categories of consumer research, the quantitative systems analysts tend to be searching for errors in existing approaches and the potential for injury in the use of products and environments. The process focuses on physiology and cognitive processes. The use of these methods can identify areas that must be addressed to decrease fatigue, stress, and injury, or reduce the number of steps needed to perform an operation. The qualitative methods tend to identify emotional and expressive aspects of customers’ expectations and focus on the potential of what a product could be. Both types of analysis are needed. The best products produce an effect that customers usually do not anticipate. They instantly fill a need no one knew existed. No one predicted that car buyers would be interested in buying a two-seat retro convertible with rear wheel drive. Not even Mazda realized how big the market was when it introduced the Miata. No one anticipated the success of a peeler with an attractive, ergonomic handle made out of black rubber with fins under a new brand named OXO. Those factors were not measured directly, but instead were anticipated by “reading” the SET Factors. Then, using form development and ergonomic research working in tandem through conceptualization cycles and refinement, the final design was developed and launched.

The challenge is in mediating these two seemingly opposite approaches to understanding human behavior. A successful product must reduce the likelihood of injury and misuse, and it must simultaneously make people feel that the product enhances their experience. Cars are an example of how human factors research has been used in the design of the interior; at the same time, the exterior look and feel of the vehicle is generally emotion based. The interior design is the result of human factors analysis that maximizes the interior space of the vehicle, thus making it comfortable, safe, and flexible. In the better designs, the interior is also visually designed to complement the exterior look and feel without compromising usability. The exterior look and feel provides a highly emotional response that customers see as either highly desirable or not. This type of response is a qualitative response that is just as important for purchase and satisfaction as the interior safety. This issue is particularly important, with the focus on smaller, more efficient cars. The interior sense of space has been significantly altered by how the seats, dashboard, windows, and minimum rear storage work in harmony to give the optimal sense of space, both real and imagined. As price of features decreases, more features are further integrated into the low-end cars as well. The Honda Fit is a number-one seller in its category of small car, and the interior could almost be described as roomy.

The design of the deployment of an airbag is critical to the safety of a driver in an accident. Failing to design this with proper ergonomics analysis can result in the death of a driver. The steering wheel itself is something the driver uses every day. The look and feel of the steering wheel is a combination of visual appeal, a cognitive understanding of controls, and an understanding of how the hand interacts with a circular form with a round cross-section. Drivers look at the steering wheel and use it every time they drive the car; its design is critical to the driving experience. The airbag deploys only in an emergency, and hopefully the driver will never need it. Both of these design features are critical to the success of the product. The look and feel of the steering wheel is important from the point of purchase through the lifetime of the vehicle; it is a long-term product detail. The airbag is not. But if the airbag fails in an accident, everyone who owns a version of the car will feel unsafe, and this could affect others shopping for a new car. The airbag requires research and testing rigor and manufacturing standards that are greater in some respects than the design of the steering wheel. The steering wheel is in the primary lifestyle impact upper right cell of the PDM discussed in Chapter 6, “Integrating Disciplines and Managing Diverse Teams,” whereas the airbag is in the secondary lifestyle impact lower right cell. However, both are important to the overall success of the product.

All the products we have reviewed have a balance between the type of human factors that is the result of research and testing, as well as the kind of research that creates insights that lead to the proper balance and expression of product form and features. Companies involved in new product development must try to merge the thinking between these two seemingly disparate approaches to understanding human behavior. For example, in the GE Adventure Series, the child-friendly interface must work in harmony with the core technology and not compromise the image or access to the technical interface that operates the imaging system.

An Integrated Approach to a User-Driven Process

It is critical that each discipline be involved in user research. Fundamental to the success of a product is a positive user experience. When all is said and done, a consumer will use the body monitoring device, drive the electric vehicle, or enjoy a margarita. The product enables users to do something they either couldn’t otherwise do or couldn’t do as well or as easily. The product also enables a fantasy of what could be. The interaction of the product with the user and the quality of the resulting activity summarize the overall product experience. If the experience meets or exceeds expectations, people will buy your product, recommend your product, and use your product. If it is poor, the customer will feel let down, frustrated, and negative. They will also tell their friends in person or online not to buy the product. The goal is to understand how to create a product that enables a user to have a positive experience initially and throughout the life span of the product.

As shown in Figure 7.1 (inner loop), surrounding the user experience is the user’s expectation of interacting with the product. This expectation has three features: First is the look and feel—does the product affect the user’s lifestyle and image appropriately or improve the aesthetic or psychological experience? Next is performance—does the product function as anticipated, and does the overall interaction with the technology enhance the overall experience? Third is what we defined in Chapter 3, “The Upper Right: The Value Quadrant,” as psycheconometrics, the psychological spending profile of a niche market—Does the product offer the value people perceive is worth paying for? The goal is to understand these expectations and translate them into product features.

Figure 7.1. User-centered design—the user’s expectation sets up attributes that are manifested through the disciplines.

The interaction of the product with the user and the quality of the resulting activity create the overall product experience.

The expectation of what the experience will be is realized by the attributes of the product (see Figure 7.1, middle loop). Users perceive the look and feel of a product through the sensory factors—the visual, tactile, auditory, olfactory, and gustatory aesthetics. The performance of a product is a direct result of the features incorporated into the product. The psycheconometric element is accomplished by focusing on a target market.

These attributes become the product and are manifested through style (creating sensory factors), technology (enabling features), and the price and brand strategy (describing cost preferences of the product and a brand appropriate for the target market), as shown in Figure 7.1 (outside loop). As the figure shows, these manifestations map directly to design, engineering, and marketing (and finance). Each discipline, then, directly affects the user’s experience with the product, and each is required to contribute to the development of the product.

Understanding the expectations of the user experience gives each discipline a direction to pursue in developing the product. The goal in developing a breakthrough product, then, is to understand the user’s expectations. We now turn to tools and methods for understanding the user.

Scenario Development (Part I)

Recall that the SET Factors are a scan of the Social trends (S), Economic forces (E), and Technological advances (T) in society. The goal is to recognize the need for a product to influence the lifestyle of a group in society—in other words, a product opportunity. After identifying that opportunity, the first step in qualitative research is to create a scenario, or story, about a typical user in the targeted activity and determine how the lack of a product makes that activity harder or less fulfilling.

The initial scenario is short (maybe a paragraph or two in length) and covers the basic elements of the opportunity. These elements include the who, what, why, how, where and when of a situation. In other words, who is the target customer, what is that customer’s need, why does the customer have that need, how is the task currently accomplished, where does the experience take place, and when does this happen? This initial scenario often captures the pain points—the problem areas and frustrations—that potential customers feel in the current state of product offerings, opening the potential to make their experience better.

For example, consider this scenario:

Ron is an independent contractor. He typically works alone or with a crew of one or two. When Ron arrives at the worksite in the morning, he drops off his larger equipment as close to the work area as possible. Setting up a work area typically means carrying sawhorses and boards, as well as large ladders and tools. Most of the equipment is heavy, and many trips to a destination far from the truck can be time and energy intensive.

If Ron can work near his pickup truck, he often uses the tailgate as a cutting or work surface—even a place for eating lunch. Ron’s truck has side-mounted toolboxes that he installed and both a ladder rack and towing hitch that he had installed professionally. This means that Ron has no free space within his truck bed and that he often has to put his tools on the ground during unloading; this is damaging to both the tools and Ron’s back.

This scenario identifies:

Who: Ron, a contractor

What: Need for flexible workspace associated with his truck

Why: No room in typically loaded truck; makeshift solutions are not satisfactory; current approach is bad on the back and tiring

How: Equipment carried and put together on the spot, or tailgate used as makeshift table

Where: Carried outside the truck bed and usable anywhere on the work site

When: Throughout the workday

We still don’t know a lot about Ron’s needs and the details of his activities. We also don’t know a lot about the solution to his dilemma. But we do know that we have a wonderful opportunity to create a product to meet Ron’s needs. We also know, from our SET Factors and informal discussions with contractors, that Ron is not alone: Many contractors have these same problems every day.T1

We use this project surrounding Ron and his needs, wants, and desires throughout this chapter to illustrate several methods of user-based research and show how this scenario eventually led to a superb and innovative after-market product for pickup trucks. This product, patented by Ford Motor Company, resulted from a 16-week part-time effort by a team of novice engineers, designers, and a marketing person who followed the user-centered iNPD process laid out in this book.

As discussed in Chapters 1, “What Drives New Product Development,” and 3, “The Upper Right: The Value Quadrant,” the SET Factors and Value Opportunities change over time. If the product meets a wider range of needs, wants, and desires, it will stay in the Upper Right for a longer time. The scenario can help create a more robust Upper Right product, one that is not sensitive to slight variations in the SET Factors and resulting VOs. When the core scenario is stated, it should be considered under different environments. For Ron, how would the scenario change if the consumer base became more “green” (that is, environmentally aware)? How would increased fuel costs affect Ron’s business? Or how will Ron’s need for workspace change as his truck becomes networked and becomes his sole office? Such context variation helps the team think in a broader context about the product opportunity.

A scenario is a powerful tool to keep the development process focused. Although the scenario might get more refined, revisiting the scenario and making sure that the evolving product meets the who-what-why-how-where-when of the scenario is critical at each step along the way. If at any time the product deviates from this description, the design team must decide whether the purpose of the product has changed (with evidence from further qualitative research) or else rethink the solution to get back on track with the scenario.

After completing an initial scenario, the next task for the team is to seek to understand in detail the activities, needs, and preferences of someone similar to the person or people in the scenario.

New Product Ethnography

During the second half of the twentieth century, companies involved in new product development looked to the social sciences for information about ergonomics and attitudes of consumers. Most recently, techniques used in the field of anthropology have been employed to aid in the preliminary stages of new product development through the use of ethnographic methods. Traditional ethnography is the art and science of describing a group or culture. It is a form of cultural anthropology that uses fieldwork to observe the group and derive patterns of behavior, belief, and activity. Fetterman6 provides a clear overview of traditional ethnography. The new form of ethnography used in product development is a blend of these traditional methods with new emerging technology for observing, recording, and analyzing social situations.7 However, new product ethnography is more than just applied anthropology. The most important element of this new form is that it is not merely descriptive, but also predictive. This new branch of ethnography has emerged as a powerful area for predicting consumer preferences for product features, form, material and color, and patterns of use and purchase. In other words, ethnography can help determine the qualities that products should possess. Wilcox8 sums up the motivation for including ethnography in the design process: “We should be concerned about the study of culture for one central reason: It is the primary determinant of what people want to buy and how they like it.”

Ethnography techniques have emerged as a research tool for both marketing and human factors. In marketing research, ethnography can help in identifying and understanding emerging trends. In human factors research, these same techniques can be used to better understand people’s patterns of use and preferences when developing the criteria for products. The use of ethnographic methods is critical in the early phases of product development because they provide deeper insights than broad statistical surveys. Existing databases compiled by market research can complement and help direct this type of research. However, broad surveys and focus groups are more useful downstream when there is a basic understanding of the user. You need to know what questions to ask to make a focus group or survey useful; ethnography helps you find out what questions are relevant.

New product ethnography provides four benefits to the product development process. The first is an in-depth understanding of a small representative sample of the intended market. Again, the goal in the early stages of the process is not to obtain statistically significant, general information about product features. Instead, it is to understand in depth the needs, wants, and desires of a market segment. Ethnography provides insight into all of these and is a keystone to understanding the everyday behavior of the customer.

The second benefit of ethnography is a focus on the consumer’s lifestyle, experiences, and patterns of use. These insights allow the team to identify the features of a product that will make it sell. But beyond features, these insights help define the essence of the product—the look, feel, function, and purpose of the product. Ethnographic insights are the difference in defining the gap between the functional generic blender and the Margaritaville Frozen Concoction Maker, the pedometer and the FIT, and the coffee shop and Starbucks. These insights can help car companies understand why some people prefer a basic pickup truck while others prefer an SUV, and still others a plug-in hybrid car.

The turnaround time between identifying the need for a product and seeing the product on the market is anywhere from six months to three or more years. Huge financial commitments must be made, from cost of design and engineering to manufacturing equipment, consumer testing, labor, marketing, and sales. Given the significant amount of money and resources at stake, it is critical that the product designed today be successful one to three years down the road. How can a company commit its resources to a guess regarding what a consumer will want to purchase in the future? Ethnography is a key to making the right decisions by removing the guesswork. So the third benefit of ethnography is predicting major shifts in consumer needs. By seeking out the essence of how people think about the world around them, what is coming into their focal point, and what is leaving, the product development team can gain insights into what needs, wants, and desires people will shift to in the near future.

Instead of just focusing on the product itself, the team must understand the levels of detail surrounding the product. How will people use the product and in what situations? What other products will people use in conjunction with this one? What activities, besides the one of focus, does the customer like to participate in? What difficulties does the customer have in the current experience? These difficulties go beyond the details of a task analysis. They exist in the storage, access, and maintenance of the product; in the environments where current products fail; and in the type of environments where people live, work, and play. Understanding the essence of the lifestyle and patterns of use of the end user is like peeling away an artichoke: The heart is at the bottom, but each leaf has meat to enjoy and contributes to the overall experience of eating an artichoke (or designing a product).

The fourth benefit for new product ethnography is the ability to monitor dynamic markets. What people like today they will probably not like tomorrow; what people liked yesterday they will like again soon. Why is rock climbing in vogue after so many years? Why do Gen Xers like to skydive and bungee-jump? Why did the PT Cruiser and Beetle become so popular when their styles had been “out” for so long, only to lose popularity to more contemporary-looking cars again? When will online streaming overtake DVDs (which overtook VHS) as the forum of choice for movies? Why did the style and ease of use of the iMac succeed when consumers had previously been obsessed with faster processing speed and more features? Ethnography can help the team see changes in the marketplace before they occur by observing the frustrations and enthusiasm of customers to aspects of technology, style, and activity.

The techniques of ethnography useful in product design include these:

• Observation—Taking a birds-eye view of a situation allows the ethnographer to obtain a (somewhat) unobtrusive understanding of the context and particular activities surrounding a product opportunity. Observation methods include the ethnographer physically being at an event or, alternatively, using video and sound recording for later analysis. (One product ethnography firm paid people to keep a camera in the living room for a week.) The videos are then analyzed, section by section, looking for interesting insights into behaviors. The result of the observation is often interpreted by the ethnographer in conjunction with data from interviews and visual stories using state-of-the-art video-editing and organizing software.

• Interviews—Within the context of use in which people encounter the product or general opportunity under consideration, interviews provide insights into the way individuals think about, understand, and relate to their behavior in relation to that part of their lifestyle. Stories about situations and objects are desired to understand the context within which a product would function. Here the interviews go much deeper than just the details of the product, into the general lifestyle or work function of the user and overall target experience. The emergence of Web-based research tools and capabilities has opened up this medium as an interview option, particularly when distance is an issue between interviewer and interviewee.

• Visual stories—Visual stories are data produced by the target users (the research subjects) themselves. They are narratives that provide insight into typical activities surrounding a particular lifestyle. Visual stories are created by participants via reusable or cellphone cameras and diaries/journals in which people record what they think is important in a defined setting. This setting might be the activity of focus, the highlights of a day, or even photos of their favorite fashion or colors.

The goal of each approach is to contribute to an overall understanding of the issues surrounding a potential product opportunity and lifestyle issue. The result is insight that leads directly to an understanding of the Value Opportunities for the product. From the resulting patterns of behavior, a model emerges that indicates the flow of activities, behaviors, attitudes, or emotions surrounding the product opportunity. For the interested reader, Martin and Hanington present an extensive set of ethnographic and other qualitative research methods in their book Universal Methods of Design.9

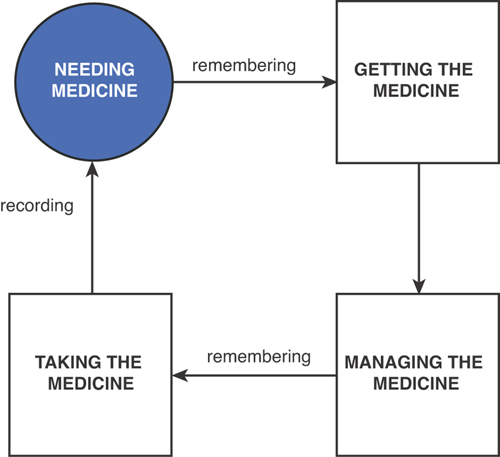

Consider the opportunity of organizing and storing medicines in the household for families. A team using ethnography to understand this opportunity visited several families in their homes and applied the ethnographic methods of observation and in-depth interviews. After analyzing the data, they derived a model of behaviors of medicine use, shown in Figure 7.2. In the model, the following loop is followed:

• Needing medicine—Someone gets sick and tries to find a remedy to feel better. This could involve getting a prescription from a doctor and learning about the medicine from the doctor.

Remembering to get the medicine is required to move to the next step.

• Getting the medicine—The sick person or a family member obtains medicine from a pharmacy, herbalist, or somewhere else. This can involve further education from the dispenser.

• Managing the medicine—The medicine is integrated into people’s lives when they create or adopt routines.

Remembering to take the medicine is required to move to the next step.

• Taking the medicine—The person consumes the medicine, possibly with other requirements, such as food.

Recording that the medicine was taken is sometimes done or desired. The process returns to “Needing medicine.”

Figure 7.2. Behavioral model of medicine taking and storage in the home, derived from ethnographic research.

No product is defined or suggested, but at every arrow or box in the model, clear opportunities for products exist.T2

As a different example, the team that focused on Ron and other contractors discovered many relevant lifestyle issues through observation and in-depth interviews. In terms of their pickup trucks, all contractors had some sort of accessories on their trucks. Few had a cap, many had ladder racks, few had behind-cab toolboxes, and most had side-mounted toolboxes. These observations showed that this market is willing to spend money to buy accessories for their truck if they are useful and help them work. The wide range of accessories and set-ups on the trucks indicated that the team was going to have to design a product that did not interfere with the present configuration of the contractors’ trucks.

All of the people interviewed had a makeshift workspace that they themselves had made at the site. This usually consisted of two sawhorses and a board to make a table. About a third of the people interviewed said that they used worktables that they bought in addition to the one they made. These tables were usually foldable tables that came with a tool and were used with only that one tool (for example, a circular saw and the factory-made, collapsible table that it attached to). Half of the people interviewed used the tailgate as a workspace. The activities at the tailgate include setting up a brake and bending material, cutting material, using it as a workbench, using it as a sawhorse for the worktable, and sitting and eating lunch.

The information gathered from the interviews led to a list of additional concerns that had to be addressed when developing the product:

• How much space does it take up?

• Where does it live on/in the truck?

• Can it have its own power source?

• Can it be removable?

Using Ethnography to Understand Parrotheads

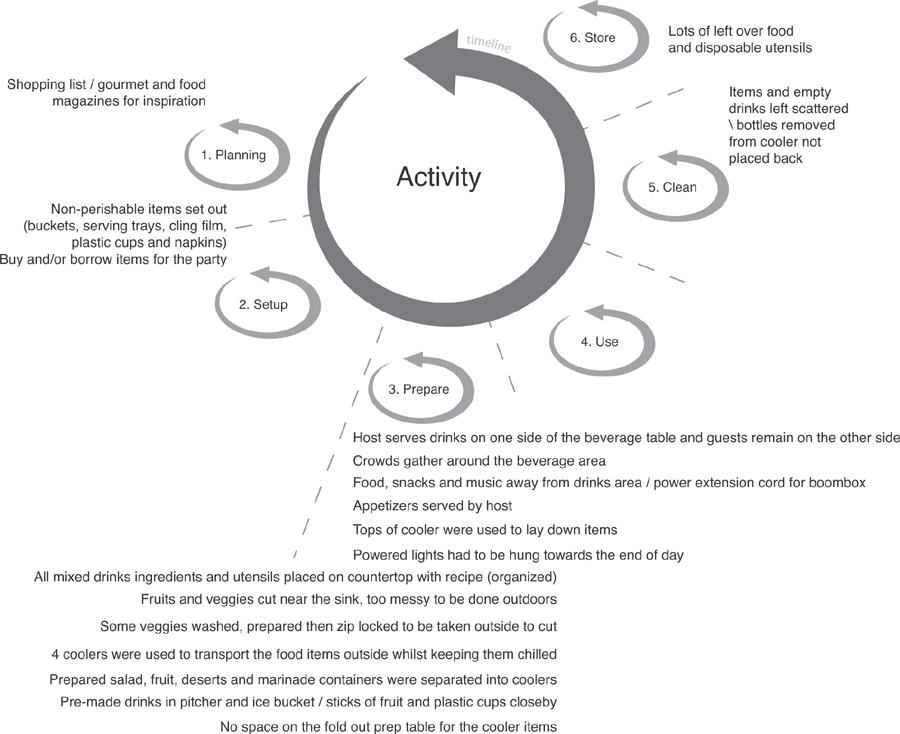

When Jarden licensed the Margaritaville brand, they did not have a particular product in mind. Altitude helped Jarden find the POG. Altitude’s team conducted two levels of product ethnography. The first goal of product ethnography is to look for insights that will inspire focused direction and identify a clear Product Opportunity Gap. The second level is conducted once the focus is there; teams need to understand what Value Opportunities will lead to product characteristics. In the first level of ethnography, the Altitude team, in collaboration with the Jarden innovation team, was looking for the right product opportunity. The team members observed Parrothead parties. They also asked Parrotheads to record visual and textual stories of their process of throwing a party. Figure 7.3 shows the text version of one family’s party from preparation to cleanup.

Figure 7.3. Activity-based ethnography model used by Altitude in user research for the Frozen Concoction Maker. This is a partial example of one family’s approach to organizing a party.

(Courtesy of Altitude and Jarden)

One thing stuck out: People liked to drink margaritas and other mixed drinks, but the current-state observations showed significant room for improvement. During outdoor parties, the challenge was going inside to make the drinks in the kitchen, away from the party; most blenders were small and could not make a lot of drinks at one time.

Another factor was the challenge of getting the right ice consistency for the drinks; they were never like the ones at the bar or restaurant. This observation led to three product insights: There was a POG for an outdoor mixed drink maker, the product had to be bigger to make more drinks, and it had to make the right ice consistency. Those became the core drivers for the product development phase. The team then moved to the second phase and started to conduct research on the successful professional mixed drink makers used in restaurants and bars. Team members found that the best product cost $5,000 and was successful because it shredded the ice rather than chopped it. The challenge for the engineers was to create a mechanism that could produce the same silky ice consistency but be manufactured and hit the right price point for a consumer market. From a price strategy, the goal was to make the product profitable above $100. The product also had to be easy to use, safe, and easy to clean.

To protect the product from the competition, the company needed to have a distinctive design that would generate a design patent, along with any utility patents for the ice production process. The design had to reflect the Margaritaville lifestyle and also allow for a unique look that could be protected by a design patent and eventual trade dress protection, to prevent cheap look-alike competitors. Altitude conducted additional research to find the right trend elements that Buffett fans would identify with and that would fit into the atmosphere of an outdoor event, reminiscent of the subtropics. Ethnographic research revealed different themes, with the theme of “Affordable Luxury” emerging as the core brand language for the product. The team determined that the product should look like a home counter top product but fit outdoors. The overall form has rounded, soft shapes and large radii with a brushed and shiny aluminum-like finish and colored plastic trim. The details and graphic elements created the trademark identity and consistent details that made the product look contemporary and high end, yet echo the fantasy lifestyle of the Florida Keys for Buffett fans. Small details such as nautical rings to individualize drinking glasses and similar symbols subtly placed on the product helped connect it to the subtropics.

The ethnographic research combined with secondary analysis of current product capabilities and the physical requirements to appropriately shave the ice led to well-defined functional considerations. The performance variables were as listed:

• Variations in ice quality, shape, density, and size

• Variations in supply water temperature, flavor, and mineral content

• Speed/control/simplicity of drink creation (at all stages)

• Melting ice in hopper, diluting mixed beverages

• Entertaining without distraction or lower performance

• Cleanability, maintenance, and replacement

• Storage (commercial machine is left out, but this one travels, gets stored, and so on).

The component variables were these:

• Shaving motor size, shape, cost, and longevity

• Mixing motor size, shape, cost, and longevity

• Shaving blade sharpness, size, shape, longevity, cost, and replacement

• Power supply

• Software/processor/firmware

• Materials/finish of everything, including carafe

By delivering on the primary research goals and the performance requirements, they were able to create a product that listed at three times the target. The extra profit per item resulted from understanding the value proposition and delivering integrated style and technology that excited the customer. The product debuted exclusively in Frontgate catalog for one year and was extremely successful, leading other retailers to want to sell the product. Altitude did some minor redesign to the Frozen Concoction Maker for other stores and to attract a broader customer base.

The front-end qualitative research led to the identification and refinement that allowed Jarden to have a new market category for the company in outdoor products and at higher-end retailers. This success not only can lead to more Margaritaville lifestyle products, including five versions of just the Frozen Concoction Maker, but also other themes as well. This is a clear case in which getting it right early and focusing on an Upper Right product with integrated technology with features, and style with brand identity at the right pricing strategy fulfilled fantasy expectations and successfully delivered a desirable experience to a broad market base.

Lifestyle Reference and Trend Analysis

Why do so many products for some target markets have the same look and feel, even though they are designed and manufactured by different companies? Clearly, companies try to copy successful and current styles. Some companies are leaders; most are followers. In order to lead, companies need to commit to competing in the Upper Right. The climb starts with understanding your consumer and anticipating their next product expectation and ends with a product or service that is unique and reflects the trends and values that your team has identified. A part of that is to introduce new styles that anticipate and meet the expectations of the market.

New styles and trends start in industries where style changes each year or even each season, as in the fashion industry. At the same time, music, film, and sports are indications of the current emotional and stylistic trends. The cartoons of Disney have clearly influenced the cartoonlike products Michael Graves has designed for Target. Early in the iPod’s growth, Apple developed a special edition with U2, with a black base and red scroll wheel, to coincide with the release of the group’s album How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb; the band members’ signatures were even engraved on the back. Michael Jordan inspired an entire industry with Nike and the Air Jordan line of shoes and that strategy has evolved into the Nike Jordan Team with 28 men and women representing basketball, baseball, football, and track and field. New products in one industry or product line are influenced by products from other lines. Herman Miller introduced the SAYL chair, an elegant design inspired by the suspension system of a bridge, creating the chair’s breathable elastomer back, the overall shape looking like a mainsail. Finally, although a company wants to be the leader, it must also respond to success from direct competitors or advances in related markets. When responding to competitors, leading companies find alternative opportunities consistent with their brand strategy and avoid copying the trend directly.

A method that integrates these factors is lifestyle reference—namely, reference to other products, styles, and activities from the target market segment. The goal of lifestyle reference is understanding what people buy, the context of how people use products, what people value, and what people define as their expectation of quality. The idea is to identify and surround yourself with a snapshot of the customer’s life, to immerse yourself in the world of the user. In their concept studios, General Motors blasts the music of the target customer and creates areas filled with products that the target generation uses. Ford has huge picture boards with a variety of images, including product photos. The idea is that the music, colors, styles, and looks give the designers a feel for who the customer is and what he or she wants in a product.

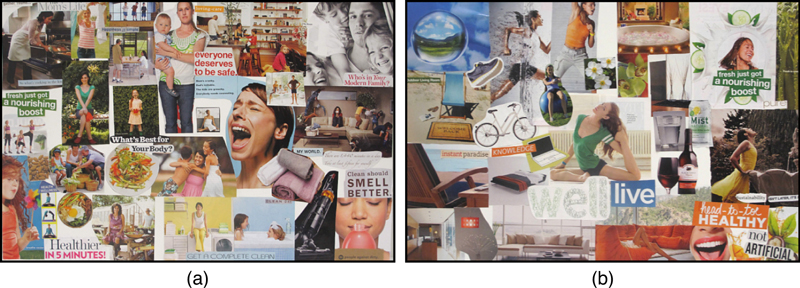

The ability to capture a lifestyle reference is really quite simple. We recommend beginning by purchasing magazines that target your market segment. For example, magazines for an older, upper-class economic group might include magazines about cooking, architecture and interior design, golf, and travel; Echo Boomer magazines might include those about mountain biking, snowboarding, music, and technology. From the magazines, create a collage, known as a mood board, of the key lifestyle images and typical products. The mood board can be organized by subject or color, or can be randomly put together to give an interpreted snapshot of the user. Figure 7.4 shows two example boards that represent the lifestyle issues surrounding the quick rejuvenation for a mother of young kids or a young professional. Both of these were target markets for a product that sought to bring the spa to one’s everyday shower.

Figure 7.4. Lifestyle reference collage of mothers of young children (a) and young professionals (b) seeking fast rejuvenation in their shower.T3

From the magazines, identify products from feature stories or advertisements. Purchase these products, or borrow and use them. Photos indicate a first look, but touching and using a product gives you a sense for the current use of materials, accents, and touch and feel of the products.

Identify music and films popular with the target group. The sense and emotional tenor from the music or the tone of imagery from a movie translates into product style.

Of course, some products can be transgenerational. Transgenerational products usually start with success in one market segment and expand to other market segments. OXO started with a universal/inclusive design focus but soon became a successful transgenerational success. The Frozen Concoction Maker started with a focus on Baby Boomer Parrotheads and quickly expanded into young markets as well. The Herman Miller Aeron and Mirra chairs were initially purchased by young entrepreneurs in dotcom firms and design companies, and then became mainstream for every type of business and user. Transgenerational products succeed because they hit a universal cord with consumers that starts in one market segment and explodes into others.

Be careful, however. Because product opportunities stem from the SET Factors, they are also targeted to a specific group of users. If the team tries to reach too broad of a market with a given product, at least initially, the product might not gain enough buy-in from any one group to succeed.

If the team tries to reach too broad of a market with a given product, at least initially, the product might not gain enough buy-in from any one group to succeed.

Trend analysis is a complement to lifestyle reference analysis and image boards. LPK in Cincinnati has a unique version of trend research that is a combination of fashion, technology, gastronomy, and emerging consumer values. This process, developed by Valerie Kramer, allows the branding company to track emerging lifestyle trends that are consumer-driven as opposed to traditional trends based on political, economic, and military data. This approach complements scenario development and ethnographic research and helps to provide actionable insights for the brands LPK manages. Following a new restaurant in Russia, experimental food in a cart in Portland, or a new fashion developing in South Africa can allow the company to anticipate potential mainstream value shifts.

Ergonomics: Interaction, Task Analysis, and Anthropometrics

Another critical area of user research surrounds ergonomics. This includes the interaction with a product, task analysis that breaks a product’s use into succinct steps, and anthropometrics that give the ranges of body dimensions and their reach.

Interaction

Ergonomics refers to the dynamic movement of people and their interaction with both static and dynamic manmade products and environments. A product has two primary and interrelated levels of interaction. Human beings experience the world through cognitive perception and physical contact. The two modes work in a dynamic cycle that produces the world we experience. Both levels of interaction must be accounted for when designing how customers navigate the use of the product. When consumers look at a product, it must be consistent with cognitive models that they have already developed. If the product is perceived as cognitively dissonant (inconsistent with former patterns), it will be difficult to use and often rejected. This is particularly relevant for breakthrough technologies. Technology-based products that seek to supplant current approaches to an experience find challenges based on new interfaces. Should a breakthrough technology include a breakthrough interface? Car companies have found that consumers accept electric vehicles better if they look like their internal combustion counterpart (see Chapter 9, “Case Studies: The Power of the Upper Right”). When the Web was blossoming, many users experienced cognitive dissonance, particularly older consumers who found screens unfamiliar and saw only one layer of the information. In contrast, a book or magazine has a front cover and a table of contents, and both can be quickly scanned. The entire product is visible, and parts are instantly accessible by physically thumbing through it. The logical order used is linear. When introducing e-books, tech companies tried to mirror many features of the paper predecessor, to maintain the feel of flipping pages and reduce that cognitive dissonance.

A product interface must account for a variety of users who vary in language, age, ability, gender, education, and cultural norms. In the medical field, a product might be used by a 60-year-old doctor, a 25-year-old nurse, and a 30-year-old medical technician who is a recent immigrant and who can barely speak English (or other local tongue). The chance for error with a product that has multiple users is high. Developing one interface that all these potential users will find easy to navigate is a challenge, and in the medical profession, an error can easily be fatal. That same product might be sold in several countries around the world. Does a multinational product have to be redesigned for each country, or should the product team try to use or develop terms and symbols that are internationally understood? Just think of the liability riding on that decision.

When people interact physically with a product, the issues of physical comfort and ease of operation also are a factor. A product can be uncomfortable by causing pain on contact or through awkward positioning or extension of the body (or any part of the body). A sports car is usually uncomfortable for tall or overweight people because the interior comfort and space is often compromised for aerodynamics. Food is often packaged in sealed containers for freshness and safety that are difficult to open. Reaching an ATM machine from a car window is often an uncomfortable activity. Office chairs are now designed to provide a stable five-star base, support the lumbar section of the spine, and adjust to different types of tasks. They have a curved front edge that helps to promote blood flow to the legs and prevents the numbing effect (falling asleep, or feeling pins and needles) that can occur when seated for too long.

Understanding the physical interaction of the product in use is important. One of the common problems with products that are tech driven is that they are often brought to market before ergonomic issues are identified. If engineers and programmers determine the cognitive and physical interface, they often design it for themselves and not for the general public. They then underdesign and create a product that is too complex for the average person to use. Industrial designers can also put form ahead of usability, creating products that look beautiful but are difficult to use. The former issue is described in Geoffrey Moore’s book Crossing the Chasm.10 Products designed using an engineering, technology-driven approach will be attractive to lead users and early adopters, who look for the latest versions of products. But this approach will not transfer to the larger consumer segments because the followers of lead users demand a simpler and friendlier interaction with a product. Moore clearly describes the problem for high-tech products, but he does not give the whole solution. The method in this book, using ethnographic, customer-centered research and integrating design, engineering, and marketing, gives a product a much higher chance of success in the larger market. This scenario is clearly illustrated in early technology such as MP3 players. The early MP3 high-tech products failed to penetrate the market until Apple established an appropriate interface and identity with the introduction of the iPod and iTunes. If ergonomic and interaction problems are not predicted and solutions integrated into the product early, they are not easy to account for later and will invariably have an effect on the style of the product. Just adding physical product features or warning labels will compromise the look and the consumer’s trust.

Discomfort can be immediate or can develop over time. Industrial and office labor has highlighted the problem of repetitive stress injury. By reducing the number of activities in a work task to improve efficiency, companies often create situations in which workers fall victim to an array of injuries that occur when they repeat the same action nonstop for days, months, or years. Carpal tunnel syndrome is the best-known example of repetitive stress injury and can appear in those who use computers or perform factory work. Scanners in supermarkets were causing a high incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome until the scanners where redesigned to be handheld. These newer, ergonomically correct scanners allow cashiers to hold the product and the scanner. This reduces the number of repeat attempts and prevents the need to continually use the same motion of dragging items over the static glass window. A masseuse now commonly comes into computer-intensive environments to release the tensions in the neck, shoulder, and arms of people who work at keyboards most of the day. Similarly, the Wave is a product designed as a response to back injury in the workplace due to lifting and climbing. Products must be easy to understand cognitively and comfortable to use physically.

Task Analysis

The goal of task analysis is to break down the current approach to solving the problem in a step-by-step manner. The result is a flow chart of each step that constitutes an activity. This can be as broad as the major steps in the day of a construction worker, an analysis of each motion that a person goes through to pick up or put down an item, or motions that the body goes through to climb or descend stairs.

If the goal is to improve the situation for a person who has physical challenges, how does that person’s process differ from the process of those without physical challenges? Here the task analysis is performed for both types of people, and the differences are compared. Of course, you might question whether the process is ideal for even the “normal” person. For example, consider the design of the OXO GoodGrips peeler. The original focus was to provide a vegetable peeler for a person with arthritis. How, then, does an arthritic person use a generic metal peeler? How does a person without arthritis use the peeler? What actions are the same and what are different? What actions cause pain for the arthritic person, and what adjustments does he or she go through to compensate for the pain? Furthermore, consider the nonarthritic person. How effective is the action of peeling with a generic peeler? Are any aspects of the process uncomfortable? This type of analysis eventually led to the GoodGrips peeler. The large grip, the improved tactile feel, and the quality of the blade all addressed the needs of the arthritic individual and, it turned out, the nonarthritic user as well. A task analysis of the GoodGrips peeler shows a significant difference in the way a person with arthritis uses the GoodGrips versus its metal predecessor.

Because of the level of detailed analysis required for a task analysis, most often the activity is first videotaped. Then the video is used to break down the task. Usually several people are videotaped, and their processes are analyzed together. The task sequence is written down step by step. If different people perform parts of the task differently, branches in the sequence occur to show the different options. If the sequences converge again, the points of convergence are shown. The approach is general and must be adapted to your own needs and context. The challenges in this process are to look carefully at each step and develop the ability to separate important steps from more trivial elements in the task. Someone who is not trained to look carefully at situations can often miss essential issues. Having a number of people with different perspectives reviewing the tape is ideal. Different disciplines are sensitive to different issues. Task analysis can also be completed through observation; it is just more difficult to focus on and replay details through the analysis.

When the task breakdown is complete, the resulting flow chart or step sequences are analyzed to indicate what is good or ineffective about the process. Also, how does one process differ from another in number of steps, number of alternatives, and number of places of difficulty? The goal in developing any product is to either reduce the number of steps in the task or make the steps more effective and easier to accomplish. A task analysis comparison of the prior state and the new state affected by your product can verify the effectiveness of the product. The comparison can also be an effective means of proving the value of the product to the company, investors, or the user. The goal is to use task analysis to help create an understanding of the current user experience in a given situation and to help identify where a product can best improve that experience.

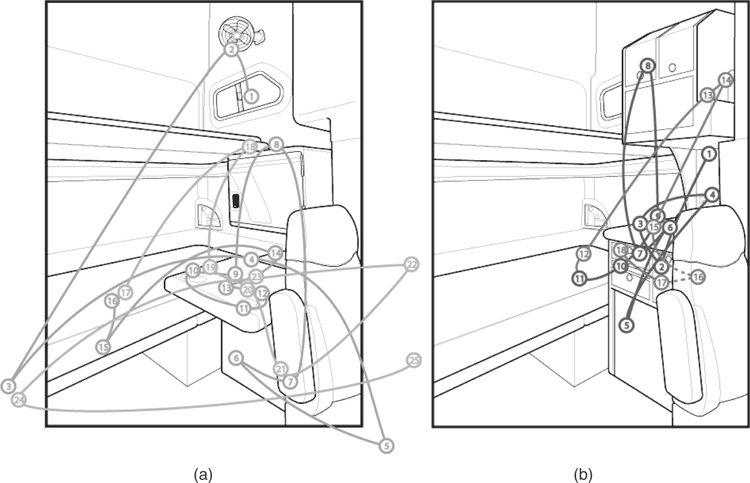

Long-haul trucks provide a home on the road for the driver. Yet typical trucks have none of the comforts of home. Even preparing a basic meal such as a sandwich is generally cumbersome, at best. One aspect of the research is to understand how a driver currently makes a simple meal in a truck. Figure 7.5(a) shows a task analysis of preparing a meal with a George Foreman Grill. Multiple steps are required to prepare and clean up the meal. There is no designated place to work, so the driver must sit on his bunk. There is no ventilation, so windows must be opened and a room fan used. Lack of storage means that items must be purchased when needed. Cleanup is even more difficult, with no trash receptacles or means to clean the grill. Figure 7.5(b) shows a task analysis of the same person using a kitchenette specifically designed for the truck. Here the number of steps is reduced, and the process of cooking and cleaning is more compact and efficient, focused on the same location. Everything the driver needs to prepare and clean up from a simple meal is provided. The original task analysis identified aspects of the process that needed to be improved, and the new one verified the effectiveness of the product.T4

Figure 7.5. Task analysis of preparing a simple meal in a long-haul truck in the current situation without (a) and in the desired situation with (b) a specifically designed kitchenette.

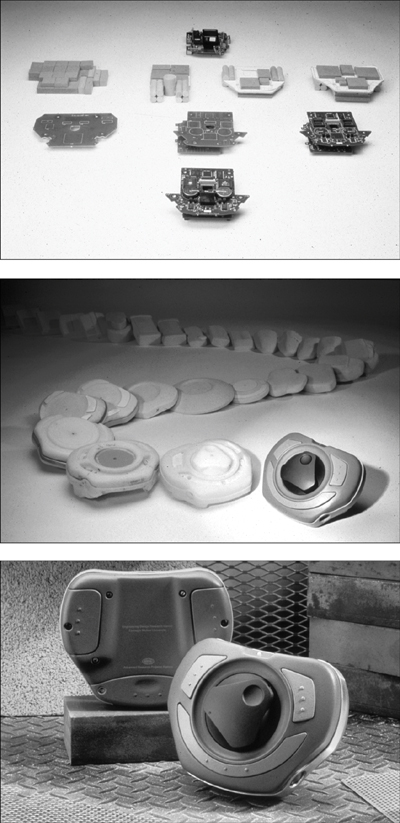

Another use of task analysis is to help organize and model process information. Consider the opportunity to clean all the nooks and crannies in the kitchen, such as the grooves inside Tupperware lids, holes in cheese graters, and blades of egg beaters. An analysis of more than 30 such objects led one team to a form representation of the majority of such nooks and crannies (shown in Figure 7.6). Such a summary of the types of slots and holes that need to be cleaned keeps the process generalized to all applications rather than fixated on a specific example.T5

Figure 7.6. A representation of nooks and crannies found in the kitchen.

Finally, a task analysis of Ron the contractor in the earlier scenario showed a significant number of activities centralized in the beginning and end of the workday. Contractors typically work in small teams or solo. Additionally, two or more trips to and from the supply store and the site are often needed before work can begin. Organizing, loading, and unloading small to medium objects in, out, and around the truck bed emerged as a primary task for this user group. Another key task is the need to remove the workspace and set it up closer to the work being done when it is not possible to locate the truck close enough. Tasks in this situation include cutting, planing, and elevating supplies.

Anthropometrics

During World War II, issues of man–machine relationships became critical. Given the size of armies and the mass production developed to equip them, designing equipment to be usable by the largest range of soldiers and understanding the limitations of use became critical. The process was an early version of what would evolve into mass marketing during the 1950s. Before that time, boots, uniforms, and bunks were designed for the average soldier, or what became known as the 50th percentile. Other military equipment had size limitations, and taller soldiers were usually banned from certain assignments. For instance, pilot cockpits, tank driver compartments, and submarines were designed for function only and, thus, limited the height and weight of the soldiers who could work comfortably in those spaces. After World War II, this changed with an analysis of and focus on a broader range of users. Over the second half of the twentieth century, anthropometric information was applied to the military and then to the manufacture of industrial and farm equipment and office work environments.

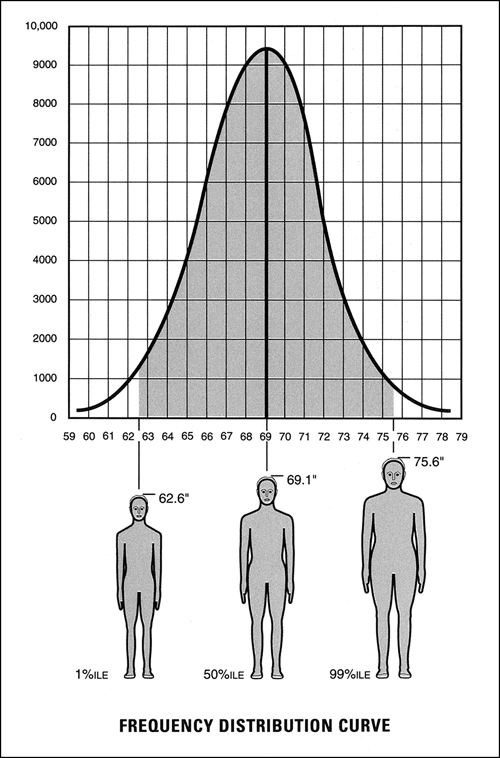

A seminal book in this area is The Measure of Man and Woman: Human Factors in Design, by Henry Dreyfuss.11 The book is in its fourth version of a publication developed by the design firm Henry Dreyfuss and Associates, originally published in 1959 and titled Measure of Man and Woman. Dreyfuss was a pioneer in the use of ergonomics for seating and work environments. The original version relied heavily on data that the military gathered, but the newest version represents decades of research gleaned from the work of the firm in a variety of product programs, including farm equipment, transportation, office environments, seating, phones, and cameras. This expanded version includes information that responded to ADA requirements. It is perhaps the best introductory book and collection of data on the market. The current version has excellent anthropometrics charts (for example, see Figure 7.7) that range from infants to seniors. It covers the ergonomics of living and working environments for fully abled people and those with disabilities.

Figure 7.7. Example Dreyfuss anthropometric chart.

(Reprinted with permission of Henry Dreyfuss Associates)

The team focusing on space for contractors to work on used the Dreyfuss charts to determine what anthropometric constraints the design would need to take into consideration. The data covers 99% of the population, ranging from the 1st percentile female to the 99th percentile male:

• Table height will range from 32 inches to 36 inches.

• As the height decreases, it becomes easier to lift heavy objects. This translates to a height of 6–8 inches below the user’s elbow.

• Table depth can range from 18 inches to 36 inches, allowing the user to reach across the work surface and access shelves above the workspace.

• Table length is dictated by the ability of the user to handle and potentially carry the work surface—no more than 6 feet, allowing for use on different-length trucks.

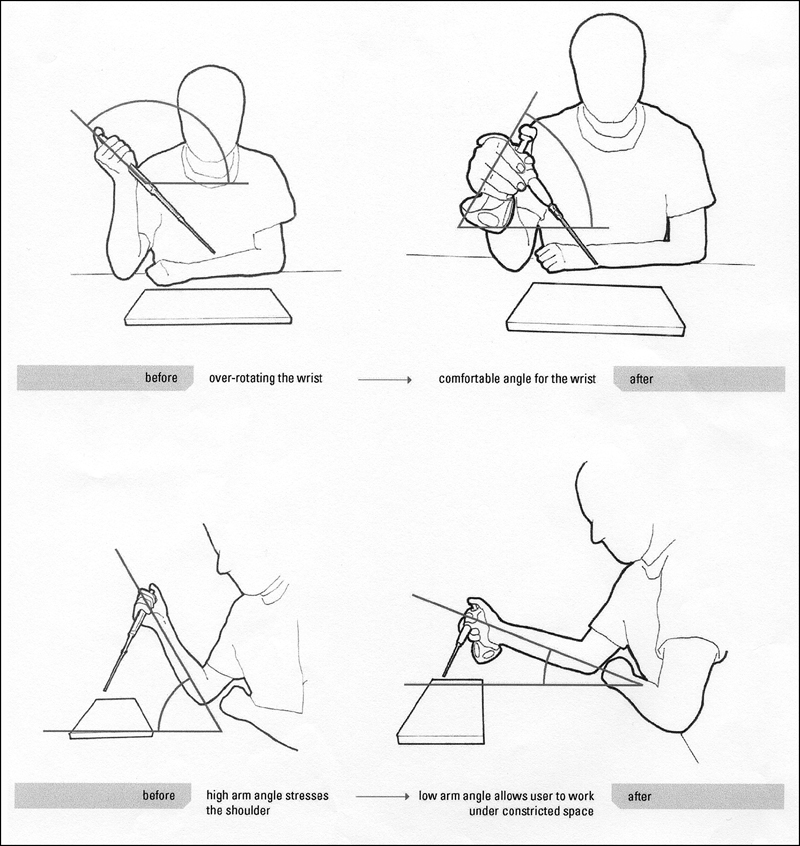

The use of anthropometric analysis in product development is complemented by a detailed understanding of biomechanics. Including nuances down to the level of muscle activation lends insights that lead to the successful design of products. The ergonomic pipette designed by VistaLab Technologies and Frog Design, discussed in Chapter 3, resulted from a detailed ergonomic analysis of physical motion of the body in conjunction with a task analysis of the steps required to use a pipette. Figure 7.8 shows a snapshot of that analysis. As Figure 7.9 shows, in developing the Aeron chair by Herman Miller, designer Bill Stumpf performed a detailed study on the variation in shapes and sizes of body types, a biometric task required to truly understand the bounds and range of interactions with the product.

Figure 7.8. Task and biomechanics analysis of the use of the original and new pipette for VistaLab.

(Reprinted with permission of Frog Design and VistaLab Technologies)

Figure 7.9. Illustration of the variation in body types of people who might sit in the Aeron Chair.

(Reprinted with permission of Stumpf Weber Associates)

Scenarios and Stories

The scenario is complemented with epic storytelling to capture the essence of the needs, wants, and desires of the key stakeholders. The scenario evolves from the ones that initially describe the POG. It emphasizes the facts and expectations surrounding the eventual product. Shane Meeker’s approach to epic storytelling that captures the journey of achieving a fantasy goal through a product, based on Christopher Vogler’s 12-step process, presents a different approach to scenario development. Epic storytelling merges the product’s potential capabilities with the vision of what the ultimate experience could be for the user, fulfilling the mantra of form and function-fulfilling fantasy.

Scenario Development (Part II)

Earlier we explained the use of scenarios in the product development process. The initial scenario helps the team understand the user profile enough to find target users for ethnographic study and task analysis, and to follow up on lifestyle reference and human factors analyses. The scenario is a reference point for the entire product development process. The result of the qualitative research, then, can and should augment the original scenario, fleshing out details and context for the use of the product. Be more specific about pain points, requirements, specifications, and interactions with the product. The revised scenario is based on primary qualitative research, as well as secondary research that provides context, details, and requirements for a successful product. The scenario for Ron was revised after observation, interviews, task analysis, and lifestyle reference, and now includes more detail and a better articulation of the issues involved, as presented in the sidebar.

Storytelling

Mastering Myth and Epic Storytelling to Drive Innovation: Shane Meeker’s New Approach to Product Stories

Shane Meeker was just named chief historian at P&G, although a more appropriate title is Epic Storyteller and Keeper of the P&G brand. It took Meeker several years to get to his current position, and he is an atypical archivist and historian. This case study is about hybridization of a career how one plus one made three for him.

Epic storytelling merges the product’s potential capabilities with the vision of what the ultimate experience could be for the user, fulfilling the mantra of form and function fulfilling fantasy.

Meeker studied industrial design and began his career as a designer at P&G. Although he loved design, his passion was always the film industry, and he even contemplated becoming a screenwriter and story developer for the movie industry. He was particularly interested in epic adventures and started to conduct research on the structure of epic narrative. Being a fan of George Lucas and Star Wars led him to Joseph Campbell’s work, epic stories, and the mythology of all cultures. Campbell had been the inspiration and advisor to George Lucas for the Star Wars movies. Meeker wanted to know more about how Lucas had integrated several mythological stories into a new epic adventure that captured the imagination of movie fans around the world. This also led him to the work of Christopher Vogler and his work on the fundamental structure that is the foundation for epic adventures. Vogler developed a 12-step, three-act narrative structure that anyone can use as a point of departure. Now Meeker had two complementary sets of innovative knowledge and method to merge: epic storytelling and industrial design.

Shane Meeker himself is a great storyteller and a dynamic presenter. He started using his visual design ability and public speaking skills to present his ideas within P&G and at various design conferences. In the book Outliers: The Story of Success,12 Gladwell describes how innovators often put in 10,000 hours to develop a unique strength and insight. Meeker had 10,000 hours as a designer and 10,000 hours in his work on myth and epic stories. Instead of becoming a movie writer, he started a new innovation capability within P&G: brand narrative. This hybrid idea came when he realized that consumers of products are all on their own epic adventure in search of treasure. It could be whiter whites for clothes, skin free of wrinkles, diapers that did not leak, or just a feeling of accomplishment. To consumers, their products are the enablers to help them overcome the obstacles of dirt, aging, care for infants, or simply how to get things done. Meeker often cites as an example that Mr. Clean is not a hero, but is the Yoda or Gandalf of cleaning in the home.

He helps the hero or heroine keep floors, glass, and counters clean. The consumer must always be the hero; brands are mentors who inspire and provide magic items to enable consumers to achieve the desired goals in life. When P&G made the commitment to elevate consumer experience through design, Meeker’s idea was the perfect empathic complement to the R&D expertise and chemical logic that makes products such as Mr. Clean work. After several years of inspiring project teams to understand the epic aspect of products, P&G appointed Meeker as company historian and leader of the Heritage Center. He replaced Ed Rider, a legend at P&G who helped establish the archives and who contributed to many of the books and articles written about P&G. In his new role, Meeker is now a steward of the P&G brand, integrating the idea of storytelling into how the archives informs and inspires employees, partners, and consumers about the mythic adventures of P&G.

When Meeker conducts his storytelling workshops, he instills in his audience the enthusiasm of college freshmen, and inspires them with his favorite movies. He has the unique ability to quote scenes from any epic movie and connect them seamlessly to theories of Joseph Campbell, Christopher Vogler, and Robert McKee. Whether at P&G or at conferences or universities, Meeker holds his audience spellbound through a combination of expertise, passion, and audience participation.

With his unique skills, Shane Meeker helps his students understand that they are on their own epic adventure. No matter where they are in the world and no matter what the context is, everyone is on a quest. The chalice they seek might seem simple to others, but it is a major part of the fulfillment we all seek. Through examples in this book, we describe how products such as Herbal Essences successfully connect with Gen Y women through understanding how a bad hair day can destroy self-esteem, or how the GE Adventure Series for children transformed the dreaded CAT scan into an epic adventure, with technicians as enablers in that adventure. Using mythic narrative as a tool is a complement to ethnographic insights and scenarios. It helps not only to create an empathic understanding, but also to elevate the everyday event to a new level of importance and inspire teams. In his book The Centaur, John Updike used Greek Mythology as a vehicle to elevate the story of a father and a young boy in a small city in Pennsylvania. Tolkien and J. K. Rowling created epic adventures as well, one through tremendous research and the other in a coffee shop. Meeker’s work is an example of using a classic tool in writing and entertainment, then redefining it for corporate life and as a methodology to drive product innovation for consumers.

The Hero’s Journey: Applying Vogler’s 12 Steps to Creating Epic Product Stories

Christopher Vogler developed 12 steps to creating epic stories, based on the writings of Joseph Campbell:

1. Ordinary World

2. Call to Adventure

3. Reluctant

4. Meet the Mentor

5. Cross the Threshold

6. Test, Allies, and Enemies

7. Approach the Inmost Cave

8. The Ordeal

9. The Reward

10. The Road Back

11. Resurrection

12. Return with the Elixir

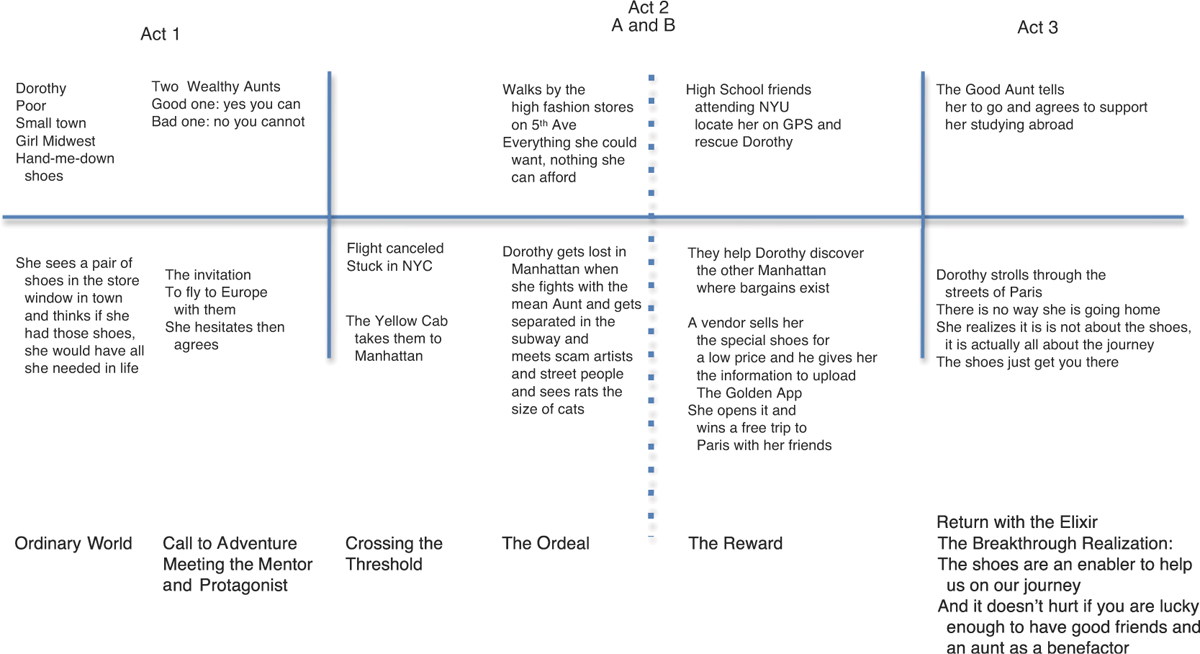

These are often placed in a three-act structure. The first act sets up the adventure and crosses the threshold from the ordinary world to the extraordinary world. The second act brings the hero/heroine to obtain the reward. The last returns the hero/heroine to the ordinary world with the reward. Inspired by Shane Meeker, when using Vogler’s steps in creating epic stories for products, it is an easy process to put the consumer in the role of hero/heroine and then run them through an elevated version of an everyday event. You can select from these steps to create a narrative; Meeker chooses about half of them. This version blends Oz with The Wiz and the design of a new pair of shoes.

Let’s focus on Dorothy, the poor farm girl who always wanted to buy new shoes and travel. She is invited by her two wealthy aunts to take a trip to Europe, but the flight out of New York is canceled and she is stranded in the city. She takes a yellow cab to Manhattan with her two aunts, who have two opposite personalities, one supportive and kind, and the other negative and hypercritical. She is finally in the city of endless shoes as she walks down Fifth Avenue. After an argument with her difficult Aunt, she wanders off on her own and gets lost. Dorothy remembers that three of her high school friends are studying at Columbia. They meet her and take her around the city on a variety of adventures. She finally gets the shoes at a bargain mall in Lower Manhattan. As a bonus with the sale, she is given a special new app that awards free trips. While at first thinking it a joke, she tries the app and ends up winning a trip for four to Paris! The good aunt who admires her newfound confidence supports a semester abroad in Paris. Dorothy walks around the City of Lights with her friends in her perfect new travel shoes. The moral of the story is: For some, home is no place to be; these shoes will take you wherever you want to go in style.

You pick the shoe company and how the features of the shoe enable Dorothy to have the perfect journey. Consider how Dorothy finds it worth fighting for the shoes and overcoming obstacles to obtain them, and consider how help from unexpected sources makes the difference between the shy farm girl and the confident young tourist in Paris. This scenario is not just about the shoes; it is all about the journey. Figure 7.12 shows Vogler’s structure for creating this story. The approach gives you a means to create exploratory scenarios to drive product development and the delivery of a brand message.

Figure 7.12. Vogler’s steps, applied to Dorothy and her search for new shoes.

Broadening the Focus

In addition to the end user, other stakeholders that interact with or are impacted by the product need to be researched. These stakeholders are external to the company, but many stakeholders internal to the company also impact and are impacted by the product’s design.

Other Stakeholders

Our focus has been the user. Fundamentally the end customer is the one who will use the product and, generally, pay for the product. Of course, multitudes of people interact with the product during the development process. Within a company, warehouse and distribution, sales, and facilities management all interact with the product. At times, these seemingly secondary functions can have a major effect on the development process. For example, if a new car cannot fit on specially designed vehicle transport trailers, the company might need to spend money and time to redesign trailers. Similarly, shipping many products is a significant added cost. Truck sizes are standard, so a slight increase in a box size might significantly reduce the number of products that can ship in a given truck. As another example, the lifecycle costs of the product, often not a focus in the design process, might have huge financial effects on the company. As discussed in the sidebar of Chapter 3, European companies have some responsibility for the disposal costs of products. Taking into account the disassembly and disposal costs of a product during its development can reduce the overall cost effects.