Chapter Eleven. Where Are They Now?

Even the best breakthrough products need to remain current. Yesterday’s breakthroughs can become outdated with new technologies, new social and lifestyle expectations, and lack of evolutionary innovation by the company. This chapter highlights the current state of products featured in the first edition of Creating Breakthrough Products. Some products are no longer on the market, some are no longer as popular, and some are as popular as ever.

Changing SET Factors

Many products featured in the first edition of this book did not make it into the current edition. We have tried to keep only the case studies that have evolved in some way, have continued to capture the marketplace, or have not been overly discussed and published since the first edition was released. In some cases, the products became outdated, their technologies cannibalized by new technological inventions. In other cases, we include a more contemporary example. The SET Factors have changed, bringing new trends and new capabilities. When the first edition came out, MP3 technology had been invented, but there was no iPod. Smartphones were just being developed—neither the iPhone nor the Palm Treo (which was cannibalized by the iPhone) had been introduced. There were no jump drives for data storage. There was no significant social media. SUVs were the rage, and the current genre of electric vehicles had not been introduced. Given these and other changes, choosing new case studies and retiring outdated ones made sense.

Two exceptions are the OXO GoodGrips products and the Crown Wave. Both of these were major case studies in the last book, and both still have a strong presence in the marketplace. OXO, in particular, continues to be a leader in kitchenware, with continuous innovation of new products, and the company is used as reference throughout the book. However, we moved both OXO and the Wave to this chapter, to make room for newer, fresher case studies that address the current SET Factors. OXO has been featured and well covered during the last decade; the Wave still sells well but has not evolved significantly at Crown as a product. Instead, Crown has focused its innovation on other lift trucks in the product line.

Here we include a status update on each of the case studies retired from this book. We begin with detailed case studies, updated as available, for the OXO GoodGrips and the Crown Wave; then we summarize the other case studies retired from the first edition.

The OXO GoodGrips Peeler

The kitchen tools designed by OXO GoodGrips won a Design of the Decade Award, presented by the Industrial Designers Society of America (IDSA) and BusinessWeek magazine. OXO products have won numerous awards in recognition of their usability, aesthetics, and innovative use of materials. Even after designing more than 850 products, the company continues to win new awards. OXO and its first product, the vegetable peeler, were the subject of a major case study in the first book. It still is a significant example of reading the SET Factors; understanding the competition; identifying how to differentiate and meet the needs, wants, and desires of the customer; and integrating the design team. We moved this case study to the start of this chapter to open up the book to new examples that illustrate breakthrough innovation. Revisiting the basis of the initial success is important, to understand how this company has continued to maintain its competitive edge in the marketplace.

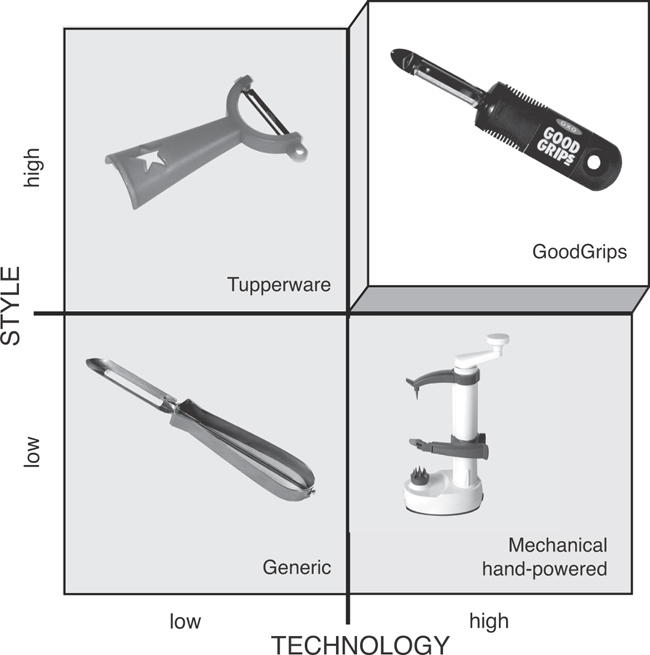

Sam Farber is a successful entrepreneur who has owned several companies. He sensed a product opportunity in the housewares industry. The insight for this opportunity came from his wife, who had developed arthritis in her hands. She liked to cook but found most cooking and food-preparation utensils painful to use. She also found that most of the solutions were ugly and stigmatized the person with disabilities while using them. In addition, these solutions often supplied only minimal relief or support. The opportunity (the POG) was not just to design cooking utensils that were comfortable to hold in your hand; the products also had to set a new aesthetic trend that would not stigmatize the user as “handicapped.” The product with the most opportunity for improvement was the vegetable peeler. The generic peeler (see Figure 11.1, Lower Left) was the technological evolutionary equivalent of the alligator; it had existed since the beginning of the industrial revolution without change. Comfort and dignity were two attributes that Farber recognized were key to making a better cooking utensil. At the same time, peelers low in style but mechanically driven were difficult to use and tended to remove more than just the peel when used, as shown in the Lower Right.

Figure 11.1. OXO Positioning Map.

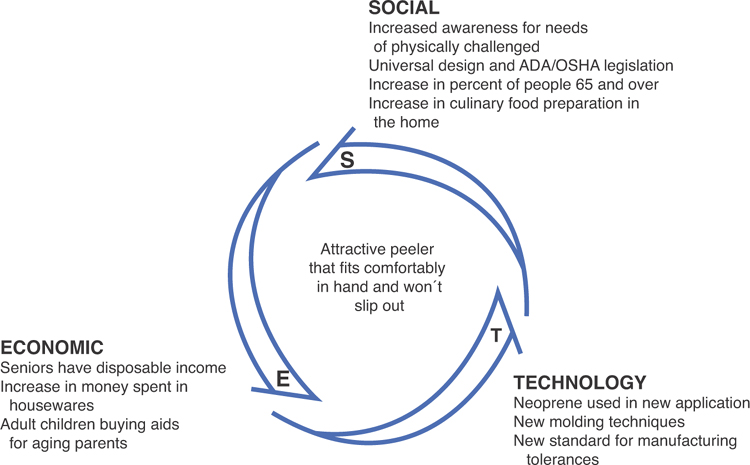

The OXO peeler (and many of the company’s other products) is an excellent example of looking for opportunities by finding long-standing products that may do the job to the level people are used to, but not to the level that they would truly like. The SET Factors (see Figure 11.2) were right—the public had become sensitive to the needs of people with physical challenges, people with those challenges demanded effective and engaging solutions, and people were not opposed to spending their resources on higher-end kitchens and products to fill them.

Figure 11.2. SET Factors that led to the GoodGrips peeler.

The product opportunity was translated into several attributes to add value. The product function was already established as useful: A peeler is a necessity for any kitchen. The two major areas for improvement were the limited usability and the ugly “form follows function” nineteenth-century aesthetic of the generic peeler. The product had to be usable by a broad range of people. The handle had to be comfortable to grip for short and long periods of use, and it had to be able to be held securely when wet. The latter feature, in particular, was responsible for the higher costs, so it needed to be perceived as being of much higher quality and innovative. The product had to be desirable. If the product ended up looking clumsy and awkward, the core market would have rejected it. The optimum result was a new aesthetic that would establish a new trend in products for the home and that all potential customers would see as usable and desirable.

Farber partnered with Smart Design to create the GoodGrips peeler (see Figure 11.3). After extensive human factors tests, an ideal overall shape was developed for the handle. The handle shape included fins carved perpendicular to the surface of the handle that allowed the index finger and thumb to fit comfortably around it and added greater control. A suitable material was sought for the handle that would make a comfortable interface between the hand and the peeler and would also provide sufficient friction to prevent the handle from slipping in the hand when wet. The result was to use Santoprene, a neoprene synthetic elastomer with a slight surface friction—soft enough to squeeze, firm enough to keep its overall shape, and capable of being cleaned in the dishwasher.

Figure 11.3. OXO GoodGrips.

(Reprinted with permission of Smart Design)

The peeler has attributes that combine aesthetics, ergonomics, ease of manufacture, and optimum use of materials (see Figure 1.16 in Chapter 1, “What Drives New Product Development”). Taking full advantage of the surface friction of Santoprene, the handle was press-fit around a plastic core. The core extended out of the handle to form a protective curve over the blade and ended in a sharp point that can be used to remove potato eyes. The plastic guard also serves as the holder for the metal blade (the only metal part left), and the blade is made out of high-grade metal that is sharper and lasts longer than the blade on the original all-metal version. A final detail was a large counter-sunk hole carved into the end of the handle, to allow owners to hang the peeler on a hook, if they preferred. This hole also added an aesthetic detail that offset the large mass of the handle and, along with the fins, gave the product a contemporary look that appealed to a much broader audience than originally targeted. When looking at the competition, it is clear that OXO defined the new Upper Right for the peeler market (see Figure 11.1).

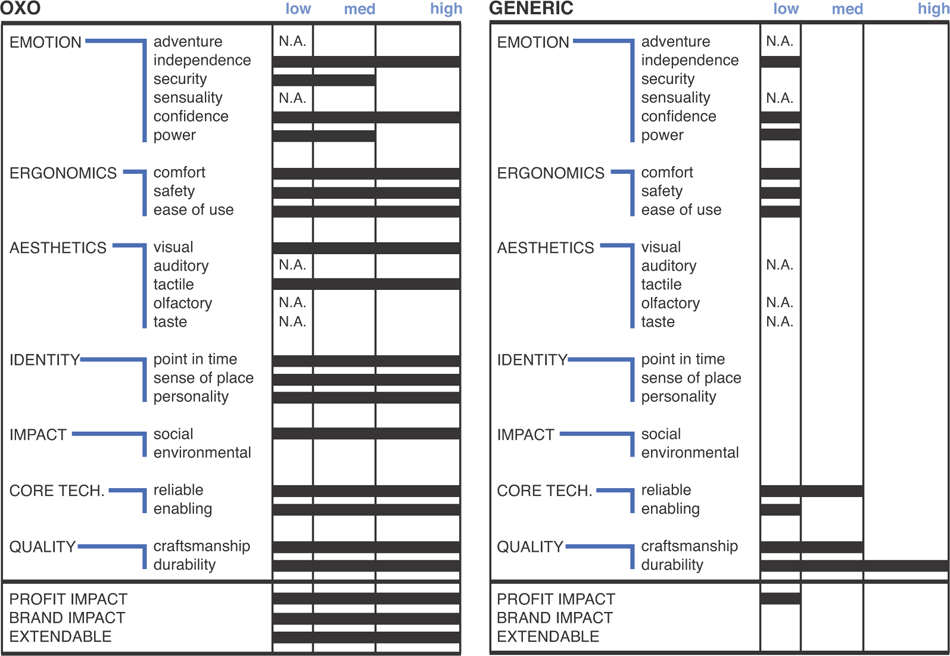

Consider a Value Opportunity Analysis of the GoodGrips peeler versus the generic metal vegetable peeler (see Figure 11.4). From a Value Opportunity perspective, the generic peeler ranks low in the emotions of independence and confidence, and meets a low level of each ergonomic attribute. The main pros are that it lasts forever (durable) and has reasonably good reliability and craftsmanship. Due to its cheap price, very little profit is realized per item. Companies that make the generic peeler make money through high sales volume. Although the peeler has been around for more than 100 years, its generic form is made by many nondescript companies and it has not led to any further product lines.

Figure 11.4. Value Opportunity Analysis of GoodGrips peeler versus generic vegetable peeler.

The GoodGrips peeler excels in its ability to meet strong emotion VOs in independence, confidence, and even security, especially for the original target market of elderly or arthritic users. The product also excels in all aspects of ergonomics, identity, core technology, and quality. The GoodGrips product has a very strong social impact, stemming from the success of the handle that enables people to hold the product with a greater sense of security. Finally, an additional part of its success is the result of the highly refined visual and tactile aesthetics. A comparison of the VO Chart for the GoodGrips peeler and the generic peeler explains how OXO is able to charge several times the cost of a generic peeler with great success.

The OXO peeler won numerous awards, and as a result of the positive praise generated by word of mouth, the product was never aggressively advertised. As adult children bought the product for their older parents, they found that they liked the product as well. Younger children found it more fun to use and more comfortable to hold. The market swelled and the momentum grew.

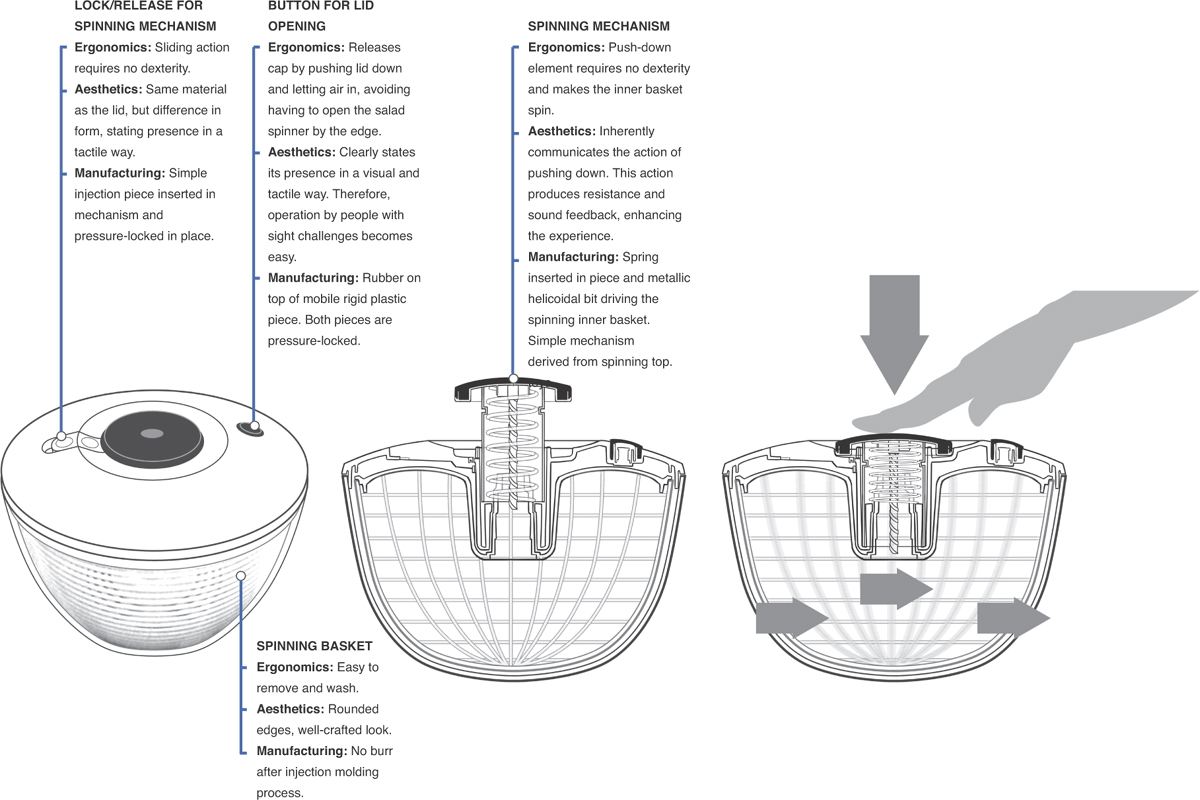

The OXO peeler is also a good example of how one successful product can become a brand strategy that can extend to other hand-held products, including teakettles, salad spinners, cleaning devices, tools, and gardening equipment. Figure 11.5 shows the clever integration of style and technology into the OXO salad spinner, which can spin with the push of a button, allowing use with a single arm or an arthritic hand.

Figure 11.5. Product details of OXO salad spinner, showing integration of style and technology.

After OXO’s initial success, a number of other housewares companies tried to copy the successful design (see Figure 2.12). Just about all of them compromised on one of the three aspects of ergonomics, lifestyle, or performance and tried to undersell the GoodGrips. Many that sought to be different attempted to create an artistic expression in the Upper Left (see Figure 11.1), significantly sacrificing the ergonomics and technology.

Sales of the peeler put OXO in the black in the first year. Through good design, the OXO brand has staying power—more than a decade later, it is still a leader in the kitchenware industry. Combining insight, design, material choice, and manufacturing processes led to the creation of a new product that has since redefined expectations on kitchen utensils.

The Crown Wave

The Wave, developed by Crown Equipment Corporation, is a success story that was featured in the first edition of the book. A decade later, the product is still selling strongly. It is a great illustration of the methods of this book. The Wave, which stands for Work Assist Vehicle (see Figure 11.6), was a breakaway product for Crown and a new product in the lift truck market. Crown management recognized that, at warehouses, the employees had difficulty in using rolling ladders to get parts. At the same time, the SET Factors highlighted that warehouse stores were growing in popularity while costs due to employee injuries were also growing. Crown turned to longtime design consultant Dave Smith to explore this emerging opportunity.

Figure 11.6. Crown Wave: product shot and product in use.

(Reprinted with permission of Crown Equipment Company)

A “just in time” mentality put pressure on store managers to maintain an active relationship between storage and retail shelves, with restocking being a constant job, not just for after-store hours. The development of warehouse store interiors with narrow aisles but large shelves and storage typically located on top of those shelves created the need for new lift equipment that can work effectively while safely operating in areas with customers in retail environments. Employers realized that long-term employees, free of injury, are more invested in the success of a store and can develop better relationships with customers, contributing to a positive atmosphere for consumers, who view shopping as a form of entertainment. During the evolution of the warehouse, storeowners have used a variety of solutions. As noted by Smith, this ranged from roller skates to rolling ladders and running shoes (Lower Left of the Positioning Map—see Figure 11.7). Although they were inexpensive, they were also an exhausting and potentially harmful experience for the stock employee. Higher-tech Lower Right solutions included scissor lift trucks, which were large, cumbersome to operate, annoying and distracting to customers, and expensive to purchase; hydraulic lifts, which were difficult to move; and robots, which were also expensive and difficult to fine-tune. A clear opportunity emerged.

Figure 11.7. Crown Wave Positioning Map.

(Image of Wave and lead designer Dave Smith with Lower Left solutions reprinted with permission of Crown Equipment Corporation)

To respond to this new POG, Crown needed to develop an entirely different product. It had to be an extension of Crown’s core ability, but at a scale and weight that Crown had not been used to. Dave Smith ran a “skunkworks” offsite interdisciplinary team for ten months to develop the initial product concept. The colocated team consisted of one engineer, two designers, a design intern, and a part-time marketing and manufacturing person. When the product concept was acceptable to both the company and potential customers, the product development process was brought back into Crown for design-to-manufacture. Creating a light-duty lift vehicle that can lift and move an operator with a minimal footprint proved to be a significant challenge for Crown. In addition to the aesthetic design impact (the visual design, product graphics, and choice of material), the team took advantage of emerging technology in the industry to add safety, nimbleness, and control to the design. Innovation came from unusual places, such as borrowing the simple two-finger control mechanism from electric wheelchairs.

A Value Opportunity Analysis of the Wave indicated the need for a series of value-added attributes. The Wave needed to promote high independence, confidence, and adventure, with very high ergonomics, appropriate aesthetics, and a strong product identity. Although the product would cost more, the technology needed to be reliable and high quality, and reduce injury. The Wave also needed to improve employee sense of security and make a series of dull tasks enjoyable and safe.

The Wave (see Figure 11.7, Upper Right) met the value proposition and introduced an original solution targeted with a midpriced, easy-to-use lift device that can maneuver through store aisles and lift a person up to 8 feet in height. The result has surpassed the original projections for the product and created a new market for Crown. Employees in stores and warehouses that use the product are reporting more effective and less stressful completion of their tasks. The product has led to higher morale and job satisfaction and is fun and easy to operate. It has allowed one operator to do a job that previously two people had to do. The Wave has since been used in a variety of new tasks.

Retired Case Studies

Here is an update on the other case studies retired from the first edition:

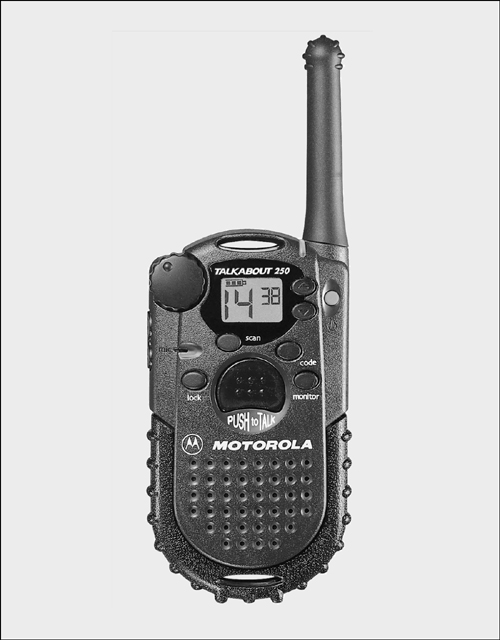

The Motorola Talkabout (see Figure 11.8) was a wonderful example of integrating style and technology to meet a clear need: family communication. A high-end walkie-talkie with its own frequency range, the Talkabout enables families in amusement parks or on the ski slopes to stay in contact. Motorola had significant off-shore competition yet did not evolve the technology, capabilities, or interaction experience with the Talkabout. This may have been because of technological evolution: with the proliferation of cellphones and text capabilities, the need for walkie-talkie-like communication became limited. The Talkabout is still for sale, but with the evolution of the SET Factors, it has run its course as a breakthrough product.

Figure 11.8. Motorola Talkabout two-way radio.

(Reprinted with permission of Motorola)

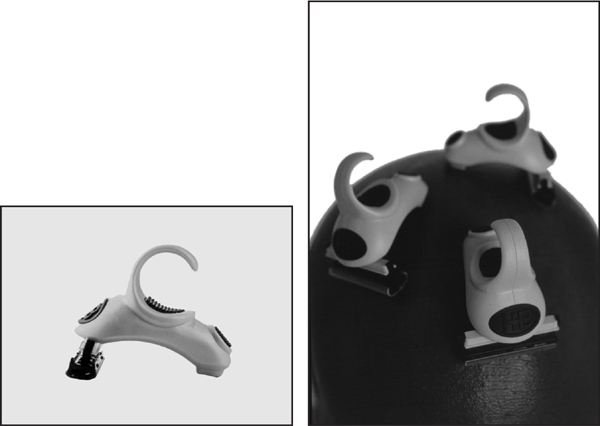

The HeadBlade (see Figure 11.9) is a razor designed for people who shave their head. A decade ago, head shaving was in vogue. Today’s audience is more limited, yet the HeadBlade is still for sale; recently, one of us saw an ad for it on a display in Manhattan featuring Telly Savalas, the icon of baldness.

Figure 11.9. The HeadBlade.

(Reprinted with permission of The HeadBlade Company)

The Zip Drive (see Figure 11.10) was a state-of-the-art approach to external data storage and transfer a decade ago. The IT industry is constantly in rapid evolution as new technologies cause last year’s capabilities to be outdated. And so the Zip Drive went the route of breakthrough to junkyard as external flash memory quickly grew to storage levels well beyond the Zip drive’s capabilities. The Zip Drive could not survive because it was quickly outdated due to cost, physical size, complexity, and storage capabilities.

Figure 11.10. Iomega Zip Drive and disk.

(Reprinted with permission of Iomega Corporation)

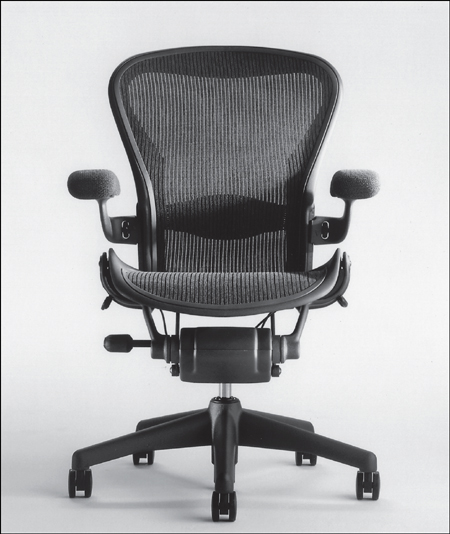

The Herman Miller Aeron Chair (see Figure 11.11) was a breakthrough in seating in the 1990s. A breathable mesh seat with an ergonomic frame, the Aeron came not in secretary, manager, and executive styles, but rather in small hips, medium hips, and large hips sizes. The Aeron represented flat management and the IPO boom of the 1990s. The Aeron is still a popular choice for office seating. Herman Miller’s innovation has focused on developing new chairs rather than evolving the Aeron. However, in this version of the book, we present a new innovation in a new area for seating: the Node, by Steelcase, with a focus on the education market.

Figure 11.11. Aeron chair.

(Reprinted with permission of Stumpf Weber Associates)

The DynaMyte (see Figure 11.12) augmentative communications device designed by Daedalus Excel (now Daedalus) for Dynavox, was a breakthrough in capabilities for people who cannot speak. The case study is a nice example of how good design can make a technology successful in the marketplace. Dynavox still makes augmentative communication devices.

Figure 11.12. DynaMyte designed by Daedalus.

(Reprinted with permission of Daedalus; photos by Larry Rippel)

The Breuer/Tornado Marathon Carpet Cleaner (see Figure 11.13), designed by HLB, was an excellent example of design and technology integration in which the delivery of technology innovation made for an easier and lighter solution for industrial carpet cleaning. The Marathon is still available but has not evolved significantly since its introduction.

Figure 11.13. Marathon cleaner.

(Reprinted with permission of Herbst Lazar Bell)

With the Kodak Single Use Camera (see Figure 11.14), Kodak did not see the change in the SET Factors and the future of digital photography. The company, once an icon of American ingenuity, went into bankruptcy at the time of the writing of this edition. Its reusable cameras are still available in tourist locations, but their prominence has become as insignificant as the sliver halide technology it uses to make film. Digital camera capabilities in people’s smartphones results in higher quality than the 400 ISO film in the reusable cameras. The case study was an illustration of how products can become more sustainable. Sustainability is now more common (in conversation, if not in practice), and the Be Green case study is a more contemporary example of sustainable design.

Figure 11.14. Kodak Max Single Use Camera.

(Reprinted with permission of the Eastman Kodak Company)

The Black & Decker Snakelight (see Figure 11.15) was a breakthrough in hands-free task lighting and an excellent example of open innovation between the company and its supplier of the flexible core. Off-shore knockoffs and the company’s lack of evolution of the product make it an interesting example of how a product can become outdated to the marketplace.

Figure 11.15. Black & Decker Snakelight.

(Reprinted with permission of Black & Decker)

The Freeplay Radio (see Figure 11.16) is a product designed to enable underdeveloped communities without electricity to have access to information through a windup radio. The case study is an example of a product able to not only meet that targeted need, but also find crossover into markets in developed nations that sail or camp, or otherwise want a radio that does not need an electrical outlet or battery. Still available, the Freeplay was replaced in this book with Design Impact’s charcoal briquette maker for rural India.

Figure 11.16. The Freeplay Radio: product image and internal schemata.

(Reprinted with permission of Freeplay Group)

In the area of SUVs, pickup trucks, and minivans, a bit more than a decade ago, the U.S. hadn’t experienced 9-11. Fuel prices were low, and consumers thought they would stay that way. Sustainability of the environment was not really a concern to the masses (assuming that it is now), and oil availability was not an issue. The U.S. auto industry was in its heyday; no one imagined GM and Chrysler going into bankruptcy. Americans were buying SUVs, large pickup trucks, and minivans at a growing rate. We had studied the design of the SUV and pickup in a major auto company, and a chapter was devoted to the auto industry. All that has changed, and although people still purchase these vehicles for strategic reasons (instead of buying a large gas-guzzling pickup just because it is cool to do so), in this edition, the SET Factors point to the growth in electric vehicles. Thus, the Leaf and the Volt are discussed in this edition.

A decade ago, the Retro Craze was in. The Mazda Miata (see Figure 11.17) is still available as a sports car at an accessible price. Its design is an excellent example of integrated design for the experience. Even the muffler was engineered for an appropriate sports car sound. Another retro car, the PT Cruiser (see Figure 11.18), didn’t enjoy the same staying power. Its retro craze had its peak, and production of the Cruiser came to an end. The PT Cruiser was an early crossover vehicle. Interestingly, it had a strong market in middle-aged women, even though it originally targeted the younger buyer. The VW Beetle (see Figure 11.19), a third retro car, is also still in production a decade later, with a redesign. The car was incredibly popular in the U.S. The Beetle brought the car from the 1960s to Baby Boomers (and others) looking to re-experience their youth.

Figure 11.17. 2001 Mazda Miata.

(Reprinted with permission of Mazda)

Figure 11.18. Chrysler PT Cruiser.

(Reprinted with permission of DaimlerChrysler Corp.)

Figure 11.19. VW Beetle.

(Photo by Larry Rippel)

As for the Apple iMac (see Figure 11.20), need we say more? The iMac redefined contemporary technological aesthetics in the home and office. The original one brought color into the computer industry and brightened up the office. Each one that followed defined a new aesthetic. The iMac and all of its descendants are still the leader in lifestyle-based computers. Apple innovates over and over again.

Figure 11.20. The original iMac.

(Reprinted with permission of Apple Computer and TBWA Chiat Day)

Summary Points

• Upper Right products and services can remain there only by injecting new innovations that are considered useful, usable, and desirable.

• Even the best breakthrough products can have a limited life if new technologies emerge.

• Breakthrough products can also have a limited life if social and lifestyle expectations change and the product does not accordingly evolve.