No home computer with a connection to the Internet is 100% safe. If this information does not concern you, it should! Although there is no way to stop a serious cracker who is intent on getting into your computer or network, there are ways to make it harder for him and to warn you when he does.

In this chapter, we discuss all aspects of securing your Linux machines. You might have wondered why we did not spread this information around the book wherever it was appropriate, but the reason is simple: If you ever have a security problem with Linux, you know you can turn to this page and start reading without having to search or try to remember where you saw a tip. Everything you need is here in this one chapter, and we strongly advise you read it from start to finish.

There are many ways in which computer attacks can be divided, but perhaps the easiest is internal, which are computer attacks done by someone with access to a computer on the local network, and external, which are attacks by someone with access to a computer through the Internet. This might sound like a trivial separation to make, but it is actually important: Unless you routinely hire talented computer hackers or allow visitors to plug computers into your network, the worst internal attack you are likely encounter is from a disgruntled employee.

Although you should never ignore the internal threat, you should arguably be more concerned with the outside world. The big bad Internet is a security vortex. Machines connected directly to the outside world can be attacked by people across the world, and invariably are, even only a few minutes after having been connected.

This situation is not a result of malicious users lying in wait for your IP address to do something interesting. Instead, canny virus writers have created worms that exploit a vulnerability, take control of a machine, and then spread it to other machines around them. As a result, most attacks today are the result of these autohacking tools; there are only a handful of true hackers around, and, to be frank, if one of these ever actually targets you seriously, it will take a mammoth effort to repel him regardless of which operating system you run.

Autohacking scripts also come in another flavor: prewritten code that exploits a vulnerability and gives its users special privileges on the hacked machine. These scripts are rarely used by their creators; instead, they are posted online and downloaded by wannabe hackers, who then use them to attack vulnerable machines.

So, the external category is itself made up of worms, serious day job hackers, and wannabe hackers (usually called script kiddies). Combined, they will assault your Internet-facing servers, and it is your job to make sure that your boxes stay up, happily ignoring the firefight around them.

On the internal front, things are somewhat more difficult. Users who sit inside your firewall are already past your primary source of defense and, worse, they might even have physical access to your machines.

Regardless of the source of the attack, there is a five-step checklist you can follow to secure your Fedora box:

Assess your vulnerability. Decide which machines can be attacked, which services they are running, and who has access to them.

Configure the server for maximum security. Install only what you need, run only what you must, and configure a local firewall.

Create worst-case-scenario policies.

Keep up-to-date with security news.

Each of these is covered in the following sections, and each is as important as the others.

It is a common mistake for people to assume that switching on a firewall makes them safe. This is not the case and, in fact, has never been the case. Each system has distinct security needs, and taking the time to customize its security layout gives you maximum security and the best performance.

The following list summarizes the most common mistakes:

Installing every package—. Do you plan to use the machine as a DNS server? If not, why have BIND installed? Go through the Add/Remove Applications dialog and ensure that you have only the software you need.

Enabling unused services—. Do you want to administer the machine remotely? Do you want people to upload files? If not, turn off SSH and FTP because they just add needless attack vectors. This goes for many other services.

Disabling the local firewall on the grounds that you already have a firewall at the perimeter—. In security, depth is crucial: The more layers someone has to hack through, the higher the likelihood she will give up or get caught.

Letting your machine give out more information than it needs to—. Many machines are configured to give out software names and version numbers by default, which is just giving hackers a helping hand.

Placing your server in an unlocked room—. If so, you might as well just turn it off now and save the worry. The exception to this is if all the employees at your company are happy and trustworthy. But why take the risk?

Plugging your machine into a wireless network—. Unless you need wireless, avoid it, particularly if your machine is a server. Never plug a server into a wireless network because it is just too fraught with security problems.

After you have ruled out these mistakes, you are onto the real problem: Which attack vectors are open on your server? In Internet terms, this comes down to which services are Internet-facing and which ports they are running on.

Two tools are often used to determine your vulnerabilities: Nmap and Nessus. Nessus scans your machine, queries the services running, checks their version numbers against its list of vulnerabilities, and reports problems.

Although Nessus sounds clever, it does not work well in many modern distributions (Fedora included) because of the way patches are made available to software. For example, if you’re running Apache 2.0.52 and a bug is found that’s fixed in 2.0.53, Fedora backports that patch to 2.0.52. This is done because the new release probably also includes new features that might break your code, so the Red Hat team takes only what is necessary and copies it into your version. As a result, Nessus will see the version 2.0.52 and think it is vulnerable to a bug that has in fact been backported.

The better solution is to use Nmap, which scans your machine and reports on any open TCP/IP ports it finds. Any service you have installed that responds to Nmap’s query is pointed out, which enables you to ensure that you have locked everything down as much as possible.

To install Nmap, select System Settings, Add/Remove Applications. Near the bottom of the list of applications is System Tools, where you can select Nmap-frontend and Nmap. Although you can use Nmap from a command line, it is easier to use with the front end—at least until you become proficient. To run the front end, select Actions, Run Application and run nmapfe. If you want to enable all Nmap’s options, you need to switch to root and run nmapfe from the console.

The best way to run Nmap is to use the SYN Stealth scan, with OS Detection and Version Probe turned on. You need to be root to enable the first two options (they are on by default when you are root), but it is well worth it. When you run Nmap (click the Scan button), it tests every port on your machine and checks whether it responds. If it does respond, Nmap queries it for version information and then prints its results onscreen.

The output lists the port numbers, service name (what usually occupies that port), and version number for every open port on your system. Hopefully, the information Nmap shows you will not be a surprise. If there is something open that you do not recognize, a hacker might have placed a backdoor on your system to allow her easy access.

You should use the output from Nmap to help you find and eliminate unwanted services. The fewer services that are open to the outside world, the more secure you are.

After you have disabled all the unneeded services on your system, what remains is a core set of connections and programs that you want to keep. However, you are not finished yet: You need to clamp down your wireless network, lock your server physically, and put scanning procedures in place (such as Tripwire and promiscuous mode network monitors).

Because wireless networking has some unique security issues, those issues deserve a separate discussion here.

Wireless networking, although convenient, can be very insecure by its very nature because transmitted data (even encrypted data) can be received by remote devices. Those devices could be in the same room; in the house, apartment, or building next door; or even several blocks away. Extra care must be used to protect the actual frequency used by your network. Great progress has been made in the past couple of years, but the possibility of a security breech is increased when the attacker is in the area and knows the frequency on which to listen. It should also be noted that the encryption method used by more wireless NICs is weaker than other forms of encryption (such as SSH) and should not be considered as part of your security plan.

Tip

Always use OpenSSH-related tools, such as ssh or sftp, to conduct business on your wireless LAN. Passwords are not transmitted as plain text, and your sessions are encrypted. Refer to Chapter 19, “Remote Access with SSH and Telnet,” to see how to connect to remote systems using ssh.

The better the physical security is around your network, the more secure it will be (this applies to wired networks as well). Keep wireless transmitters (routers, switches, and so on) as close to the center of your building as possible. Note or monitor the range of transmitted signals to determine whether your network is open to mobile network sniffing—now a geek sport known as war driving. (Linux software is available at http://sourceforge.net/project/showfiles.php?group_id=57253.) An occasional walk around your building not only gives you a break from work, but can also give you a chance to notice any people or equipment that should not be in the area.

Keep in mind that it takes only a single rogue wireless access point hooked up to a legitimate network hub to open access to your entire system. These access points can be smaller than a pack of cigarettes, so the only way to spot them is to scan for them with another wireless device.

The next step toward better security is to use secure passwords on your network and ensure that users use them as well, especially the root password. If the root password on just one machine is cracked, the whole network is in trouble. For somewhat more physical security, you can force the use of a password with the LILO or GRUB bootloaders, remove bootable devices such as floppy and CD-ROM drives, or configure a network-booting server for Fedora. This approach is not well supported or documented at the time of this writing, but you can read about one way to do this in Brieuc Jeunhomme’s Network Boot and Exotic Root HOWTO, available at http://www.tldp.org/HOWTO/Network-boot-HOWTO/. You can also read more about GRUB and LILO in Chapter 40, “Kernel and Module Management.”

Also, keep in mind that some studies show that as many as 90% of network break-ins are by current or former employees. If a person no longer requires access to your network, lock out access or, even better, remove the account immediately. A good security policy also dictates that any data associated with the account first be backed up and retained for a set period of time to ensure against loss of important data. If you are able, remove the terminated employee from the system before he leaves the building.

Finally, be aware of physical security. If a potential attacker can get physical access to your system, getting full access becomes trivial. Keep all servers in a locked room, and ensure that only authorized personnel are given access to clients.

Tripwire is a security tool that checks the integrity of normal system binaries and reports any changes to syslog or by email. Tripwire is a good tool for ensuring that your binaries have not been replaced by Trojan horse programs. Trojan horses are malicious programs inadvertently installed because of identical filenames to distributed (expected) programs, and they can wreak havoc on a breached system.

Fedora does not include the free version of Tripwire, but it can be used to monitor your system. To set up Tripwire for the first time, go to http://www.tripwire.org/, and then download and install an open-source version of the software. After installation, run the twinstall.sh script (found under /etc/tripwire) as root like so:

# /etc/tripwire/twinstall.sh

----------------------------------------------

The Tripwire site and local passphrases are used to

sign a variety of files, such as the configuration,

policy, and database files.

Passphrases should be at least 8 characters in length

and contain both letters and numbers.

See the Tripwire manual for more information.

----------------------------------------------

Creating key files...

(When selecting a passphrase, keep in mind that good passphrases typically

have upper and lower case letters, digits and punctuation marks, and are

at least 8 characters in length.)

Enter the site keyfile passphrase:

You then need to enter a password of at least eight characters (perhaps best is a string of random madness, such as 5fwkc4ln) at least twice. The script generates keys for your site (host) and then asks you to enter a password (twice) for local use. You are then asked to enter the new site password. After following the prompts, the (rather extensive) default configuration and policy files (tw.cfg and tw.pol) are encrypted. You should then back up and delete the original plain-text files installed by Fedora’s RPM package.

To then initialize Tripwire, use its --init option like so:

# tripwire --init

Please enter your local passphrase:

Parsing policy file: /etc/tripwire/tw.pol

Generating the database...

*** Processing Unix File System ***

....

Wrote database file: /var/lib/tripwire/shuttle2.twd

The database was successfully generated.

Note that not all the output is shown here. After Tripwire creates its database (which is a snapshot of your file system), it uses this baseline along with the encrypted configuration and policy settings under the /etc/tripwire directory to monitor the status of your system. You should then start Tripwire in its integrity-checking mode, using a desired option. (See the tripwire manual page for details.) For example, you can have Tripwire check your system and then generate a report at the command line, like so:

# tripwire -m c

No output is shown here, but a report is displayed in this example. The output could be redirected to a file, but a report is saved as /var/lib/tripwire/report/hostname-YYYYMMDD-HHMMSS.twr (in other words, using your host’s name, the year, the month, the day, the hour, the minute, and the seconds). This report can be read using the twprint utility, like so:

# twprint --print-report -r /var/lib/tripwire/report/shuttle2-20020919-181049.twr | less

Other options, such as emailing the report, are supported by Tripwire, which should be run as a scheduled task by your system’s scheduling table, /etc/crontab, on off-hours. (It can be resource intensive on less powerful computers.) The Tripwire software package also includes a twadmin utility you can use to fine-tune or change settings or policies or to perform other administrative duties.

Do not ever advertise that you have set a NIC to promiscuous mode. Promiscuous mode (which can be set on an interface by using ifconfig’s promisc option) is good for monitoring traffic across the network and can often allow you to monitor the actions of someone who might have broken into your network. The tcpdump command also sets a designated interface to promiscuous mode while the program runs; unfortunately, the ifconfig command does not report this fact while tcpdump is running! Keep in mind that this is one way a cracker will use to monitor your network to gain the ever-so-important root password.

Note

Browse to http://www.redhat.com/docs/manuals/ to read about how to detect unauthorized network intrusions or packet browsing (known as network sniffing). You can use the information to help protect your system. Scroll down the page and click the Security guide link.

Do not forget to use the right tool for the right job. Although a network bridge can be used to connect your network to the Internet, doing so would not be a good option. Bridges have almost become obsolete because they forward any packet that comes their way, which is not good when a bridge is connected to the Internet. A router enables you to filter which packets are relayed.

In the right hands, Linux is every bit as vulnerable to viruses as Windows is. That might come as a surprise to you, particularly if you made the switch to Linux on the basis of its security record. However, the difference between Windows and Linux is that it is much easier to secure against viruses on Linux. Indeed, as long as you are smart, you need never worry about them. Here is why:

Linux never puts the current directory in your executable path, so typing

lsruns/bin/lsrather than anylsin the current directory.A non-root user is only able to infect files he has write access to, which is usually only the files in his home directory. This is one of the most important reasons for never using the root account longer than you need to!

Linux forces you to mark files as executable, so you can’t accidentally run a file called

myfile.txt.exe, thinking it was just a text file.By having more than one common web browser and email client, Linux has strength through diversity: Virus writers cannot target one platform and hit 90% of the users.

Despite saying all that, Linux is susceptible to being a carrier for viruses. If you run a mail server, your Linux box can send virus-infected mails on to Windows boxes. The Linux-based server would be fine, but the Windows client would be taken down by the virus.

In this situation, you should consider a virus scanner for your machine. You have several to choose from, both free and commercial. The most popular free suite is Clam AV (http://www.clamav.net/), but Central Command, BitDefender, F-Secure, Kaspersky, McAfee, and others all compete to provide commercial solutions—look around for the best deal before you commit.

Always use a hardware-based or software-based firewall on computers connected to the Internet. Fedora includes a graphical firewall configuration client named system-config-securitylevel, along with a console-based firewall client named lokkit. Use these tools to implement selective or restrictive policies regarding access to your computer or LAN.

Start the lokkit command from a console or terminal window. You must run this command as root; otherwise, you will see an error message like this:

$ /usr/sbin/lokkit

ERROR - You must be root to run lokkit.

Use the su command to run lokkit like this:

$ su -c "/usr/sbin/lokkit"

After you press Enter, you see a dialog as shown in Figure 35.1. Press the Tab key to navigate to enable or disable firewalling. You can also customize your firewall settings to allow specific protocols access through a port and to designate an ethernet interface for firewalling if multiple NICs are installed. Note that you can also use a graphical interface version of lokkit by running the gnome-lokkit client during an X session.

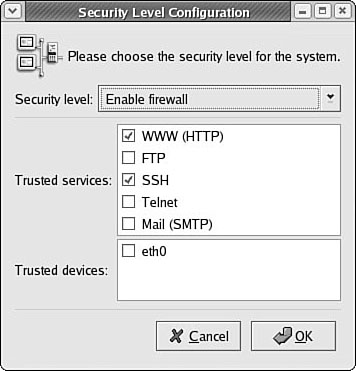

Using system-config-securitylevel is a fast and easy way to implement a simple packet-filtering ruleset with filtering rules used to accept or reject TCP and UDP packets flowing through your host’s ethernet or designated device, such as eth0 or ppp0. The rules are created on-the-fly and implemented immediately in memory using iptables.

Start system-config-securitylevel from the System Settings menu’s Security level menu item. You are prompted for the root password and the client’s window then appears. Figure 35.2 shows firewalling enabled for the eth0 ethernet device, allowing incoming secure shell and HTTP requests.

You can use Fedora to create a custom firewall, perhaps supporting IP masquerading (also known as NAT) by using either ipchains or iptables. You’ll find two sample scripts under the /usr/share/doc/rp-pppoe/configs directory; these are used when connecting to the Internet using a digital subscriber line (DSL).

No one likes planning for the worst, which is why two-thirds of the population do not have a will. It is a scary thing to have your systems hacked: One or more criminals have broken through your carefully laid blocks and caused untold damage to the machine.

Your boss, if you have one, will want a full report of what happened and why, and your users will want their email when they sit down at their desks in the morning. What to do?

If you ever do get hacked, nothing will take the stress away entirely. However, if you take the time to prepare a proper response in advance, you should at least avoid premature aging. Here are some tips to get you started:

Do not just pull the network cable out—. This alerts the hacker that he has been detected, which rules out any opportunities for security experts to monitor for that hacker returning and actually catch him.

Inform only the people that need to know—. Your boss and other IT people are at the top of the list; other employees are not. Keep in mind that it could be one of the employees behind the attack, and this tips them off.

If the machine is not required and you do not want to trace the attack, you can safely remove it from the network—. However, do not switch it off because some backdoors are enabled only when the system is rebooted.

Make a copy of all the log files on the system and store them somewhere else—. These might have been tampered with, but they might contain nuggets of information.

Check the

/etc/passwdfile and look for users you do not recognize—. Change all the passwords on the system, and remove bad users.Check the output of

ps auxfor unusual programs running—. Also check to see whether anycronjobs are set to run.Look in

/var/wwwand see whether any web pages are there that should not be.Check the contents of the

.bash_historyfiles in the home directories of your users—. Are there any recent commands for the root user?If you have worked with external security companies previously, call them in for a fresh audit—. Hand over all the logs you have, and explain the situation. They will be able to extract all the information from the logs that is possible.

Start collating backup tapes from previous weeks and months—. Your system might have been hacked long before you noticed, so you might need to roll back the system more than once to find out when the attack actually succeeded.

Download and install Rootkit Hunter from

http://www.rootkit.nl/projects/rootkit_hunter.html—. This searches for (and removes) the types of files that bad guys leave behind for their return.

Keep your disaster recovery plan somewhere safe; saving it as a file on the machine in question is a very bad move!

A multitude of websites relate to security. One in particular hosts an excellent mailing list. The site is called Security Focus, and the mailing list is called BugTraq. BugTraq is well-known for its unbiased discussion of security flaws. Be warned: It receives a relatively large amount of traffic (20–100+ messages daily).

Security holes are often discussed on BugTraq before the software makers have even released the fix. The Security Focus site has other mailing lists and sections dedicated to Linux in general and is an excellent resource.

http://www.redhat.com/docs/manuals/linux/RHL-9-Manual/custom-guide/s1-basic-firewall-gnomelokkit.html—Red Hat’s guide to basic firewall configuration. Newer documentation will appear at http://fedora.redhat.com/.

http://www.insecure.org/nmap/—This site contains information on Nmap.

http://www.securityfocus.com/—The Security Focus website.

http://www.tripwire.org/—Information and download links for the open-source version of Tripwire.