Over time, it has become a lot more difficult to “game” the search engines and a lot easier to fall victim to a search engine penalty or outright ban. It is hard to recover from these.

Consequences can include ranking penalties, removal of the site’s “voting” power (i.e., ability to pass PageRank), incomplete indexation (i.e., a partial site ban), or, worst of all, a total site ban.

Not even the largest corporations spending big dollars on Google AdWords are immune. For example, BMW had its entire BMW.de site banned from Google for a period of time because it created doorway pages—pages full of keyword-rich copy created solely for the search engine spiders and never for human viewing. To add insult to injury, Google engineer Matt Cutts publicly outed BMW on his blog. He made an example of BMW, and all of the SEO community became aware of the carmaker’s indiscretions.

Search engines rely primarily on automated means for detecting spam, with some auxiliary assistance from paid evaluators, spam vigilantes, and even your competitors. Search engineers at Google, Yahoo!, and Microsoft write sophisticated algorithms to look for abnormalities in inbound and outbound linking, in sentence structure, in HTML coding, and so on.

As far as the search engines are concerned, SEO has an acceptable side and an unacceptable side. In general terms, all types of actions intended to boost a site’s search engine ranking without improving the true value of a page can be considered spamming.

Each search engine has different published guidelines. Here is where you can find them:

Google’s Webmaster Guidelines are located at http://www.google.com/webmasters/guidelines.html.

Yahoo! Search Content Quality Guidelines are located at http://help.yahoo.com/help/us/ysearch/basics/basics-18.html.

Bing Guidelines for Successful Indexing are located at http://help.live.com/help.aspx?mkt=en-us&project=wl_webmasters.

Each search engine has varying degrees of tolerance levels for various SEO tactics. Anything that violates these guidelines, pollutes the search results with irrelevant or useless information, or would embarrass you if your Google AdWords or Yahoo! rep discovered it, is unsustainable and should be avoided.

There’s a big difference between “search-engine-friendly” and crossing the line into spam territory. “Search-engine-friendly” can mean, for example, that the site is easily accessible to spiders, even if it is database-driven; that HTML code is streamlined to minimize the amount of superfluous code; that important headings, such as product names, are set apart from the rest of the text (e.g., with H1 tags) and contain relevant keywords; or that link text is contextual, instead of comprising just “click here” or “more info” references.

Contrast these basic SEO practices with the following manipulative search engine spam tactics:

Serving pages to the search engines that are useless, incomprehensible, unsuitable for human viewing, or otherwise devoid of valuable content—such as doorway pages, which SEO vendors may refer to by more innocuous names, including “gateway pages,” “bridge pages,” “jump pages,” “attraction pages,” “advertising pages,” “channel pages,” “directory information pages,” “search engine entry pages,” “satellite sites,” “mini sites,” “magnet sites,” or “shadow domains.” Whatever you call them, by definition they are created for the sole purpose of boosting search engine ranking.

Creating sites with little useful unique content. There are many techniques for doing this, including:

Duplicating pages with minimal or no changes and exposing them to the same search engines under new URLs or domains.

Machine-generating content to chosen keyword densities (e.g., using Markov chains; you can read more about these techniques at http://en.kerouac3001.com/markov-chains-spam-that-search-engines-like-pt-1-5.htm, but they are not recommended).

Incorporating keyword-rich but nonsensical gibberish (also known as spamglish) into site content.

Creating a low-value site solely for affiliate marketing purposes (see the upcoming subsection on duplicate content for a more complete definition of thin affiliate).

Repeating the same keyword phrase in the title tag, the H1 tag, the first

alttag on the page, the meta description, the first sentence of body copy, and the anchor text in links pointing to the page.Targeting obviously irrelevant keywords.

Concealing or obscuring keyword-rich text or links within the HTML of a page so that it is not visible or accessible by human users (within comment tags,

noscripttags,noframetags, colored text on a similarly colored background, tiny font sizes, layers, or links that don’t show as links to users because they are not highlighted in some manner, such as with an underline).Hijacking or stealing content from other sites and using it as fodder for search engines. This is a practice normally implemented using scrapers. Related to this is a practice known as splogging: creating blogs and posting stolen or machine-generated content to them.

Purchasing links for the purpose of influencing search rankings.

Participating in link farms (which can be distinguished from directories in that they are less organized and have more links per page) or reciprocal linking schemes (link exchanges) with irrelevant sites for the purpose of artificially boosting your site’s importance.

Peppering websites’ guest books, blogs, or forums in bulk with keyword-rich text links for the purpose of artificially boosting your site’s importance.

Conducting sneaky redirects (immediately redirecting searchers entering your site from a keyword-rich page that ranks in the search engine to some other page that would not rank as well).

Cloaking, or detecting search engine spiders when they visit and modifying the page content specifically for the spiders to improve rankings.

Buying expired domains with high PageRank, or snapping up domain names when they expire with the hope of laying claim to the previous site’s inbound links.

Google-bowling, or submitting your competitors to link farms and so on so that they will be penalized.

These tactics are questionable in terms of effectiveness and dubious in the eyes of the search engines, often resulting in being penalized by or banned from the search engines—a risk that’s only going to increase as engines become more aggressive and sophisticated at subverting and removing offenders from their indexes. We do not advocate implementing these tactics to those interested in achieving the long-term benefits of SEO.

The search engines detect these tactics, not just by automated means through sophisticated spam-catching algorithms, but also through spam reports submitted by searchers—and yes, by your competitors. Speaking of which, you too can turn in search engine spammers, using the forms located at the following URLs:

A lot of times marketers don’t even know they’re in the wrong. For example, some years ago JC Penney, engaged an SEO vendor that used the undesirable tactic of doorway pages. Consequently, a source at Yahoo! confirmed, unbeknownst to JC Penney its entire online catalog with the exception of the home page was banned by Yahoo! for many months. Over time, this must have cost the merchant a small fortune.

Marketers can even get caught in the crossfire without necessarily

doing anything wrong. For example, search engines much more heavily

scrutinize pages that show signs of potential deception, such as

no-archive tags, noscript tags,

noframe tags, and cloaking—even though

all of these can be used ethically.

There is a popular myth that SEO is an ongoing chess game between SEO practitioners and the search engines. One moves, the other changes the rules or the algorithm, then the next move is made with the new rules in mind, and so on. Supposedly if you don’t partake in this continual progression of tactic versus tactic, you will not get the rankings lift you want.

For ethical SEO professionals, this is patently untrue. Search engines evolve their algorithms to thwart spammers. If you achieve high rankings through SEO tactics within the search engines’ guidelines, you’re likely to achieve sustainable results.

Seeing SEO as a chess game between yourself and the search engines is often a shortsighted view. Search engines want to provide relevant search results to their users. Trying to fool the search engines and take unfair advantage using parlor tricks isn’t a sustainable approach for anybody—the company, its SEO vendor, the search engine, or the search engine’s users. It is true, however, that tactics, once legitimately employed, can become less effective, but this is usually due to an increased number of companies using the same tactic.

You can spot a poor-quality site in many ways. Search engines rely on a wide range of signals as indicators of quality. Some of the obvious signals are site owners who are actively spamming the search engines—for example, if the site is actively buying links and is discovered.

However, there are also less obvious signals. Many such signals mean nothing by themselves and gain significance only when they are combined with a variety of other signals. When a number of these factors appear in combination on a site, the likelihood of it being seen as a low-quality or spam site increases.

Here is a long list of some of these types of signals:

Short registration period (one year, maybe two)

High ratio of ad blocks to content

JavaScript redirects from initial landing pages

Use of common, high-commercial-value spam keywords such as mortgage, poker, texas hold ‘em, porn, student credit cards, and related terms

Many links to other low-quality spam sites

Few links to high-quality, trusted sites

High keyword frequencies and keyword densities

Small amounts of unique content

Very few direct visits

Registered to people/entities previously associated with untrusted sites

Not frequently registered with services such as Yahoo! Site Explorer, Google Webmaster Central, or Bing Webmaster Tools

Rarely have short, high-value domain names

Often contain many keyword-stuffed subdomains

More likely to have longer domain names

More likely to contain multiple hyphens in the domain name

Less likely to have links from trusted sources

Less likely to have SSL security certificates

Less likely to be in directories such as DMOZ, Yahoo!, Librarian’s Internet Index, and so forth

Unlikely to have any significant quantity of branded searches

Unlikely to be bookmarked in services such as My Yahoo!, Delicious, Faves.com, and so forth

Unlikely to get featured in social voting sites such as Digg, Reddit, Yahoo! Buzz, StumbleUpon, and so forth

Unlikely to have channels on YouTube, communities on Facebook, or links from Wikipedia

Unlikely to be mentioned on major news sites (either with or without link attribution)

Unlikely to register with Google/Yahoo!/MSN Local Services

Unlikely to have a legitimate physical address/phone number on the website

Likely to have the domain associated with emails on blacklists

Often contain a large number of snippets of “duplicate” content found elsewhere on the Web

Unlikely to contain unique content in the form of PDFs, PPTs, XLSs, DOCs, and so forth

Frequently feature commercially focused content

Many levels of links away from highly trusted websites

Rarely contain privacy policy and copyright notice pages

Rarely listed in the Better Business Bureau’s Online Directory

Rarely contain high-grade-level text content (as measured by metrics such as the Flesch-Kincaid Reading Level)

Rarely have small snippets of text quoted on other websites and pages

Cloaking based on user-agent or IP address is common

Rarely contain paid analytics tracking software

Rarely have online or offline marketing campaigns

Rarely have affiliate link programs pointing to them

Less likely to have .com or .org extensions; more likely to use .info, .cc, .us, and other cheap, easily obtained top-level domains (TLDs)

Almost never have .mil, .edu, or .gov extensions

Rarely have links from domains with .edu or .gov extensions

Almost never have links from domains with .mil extensions

Likely to have links to a significant portion of the sites and pages that link to them

Extremely unlikely to be mentioned or linked to in scientific research papers

Unlikely to use expensive web technologies (Microsoft Server and coding products that require a licensing fee)

Likely to be registered by parties who own a very large number of domains

More likely to contain malware, viruses, or spyware (or any automated downloads)

Likely to have privacy protection on the Whois information for their domain

Some other signals would require data from a web analytics tool (which Google may be able to obtain from Google Analytics):

Rarely receive high quantities of monthly visits

Rarely have visits lasting longer than 30 seconds

Rarely have visitors bookmarking their domains in the browser

Unlikely to buy significant quantities of PPC ad traffic

Rarely have banner ad media buys

Unlikely to attract significant return traffic

For many, possibly even most, of these signals, there are legitimate reasons for a site to be doing something that would trigger the signal. Here are just a few examples:

Not every site needs an SSL certificate.

Businesses outside the United States will not be in the Better Business Bureau directory.

The site may not be relevant to scientific research papers.

The publisher may not be aware of Google Webmaster Tools or Bing Webmaster Tools.

Very few people are eligible for an .edu, .gov, or .mil TLD.

These are just a few examples meant to illustrate that these signals all need to be put into proper context. If a site conducts e-commerce sales and does not have an SSL certificate, that makes that a stronger signal. If a site says it is a university but does not have an .edu TLD, that is also a stronger signal.

Many legitimate sites will have one or more of these signals associated with it. For example, there are many good sites with an .info TLD. Doing one, two, or three of these things is not normally going to be a problem. However, sites that do 10, 20, or more of them may well have a problem.

Search engines supplement their spam fighting by allowing users to submit spam reports. For example, Google provides a form for reporting spam at http://www.google.com/contact/spamreport.html. A poll at Search Engine Roundtable in May 2008 showed that 31% of respondents reported their competitors as spammers in Google. The bottom line is that having your competitor report you is a real risk.

In addition, the search engines can and do make use of human reviewers who conduct quality reviews. In fact, in 2007 a confidential Google document called the “Spam Recognition Guide for Raters” was leaked to the public (and it is still available at http://www.searchbistro.com/spamguide.doc). The guide delineates some of the criteria for recognizing search engine spam, such as whether the site is a thin affiliate.

As we discussed in Content Management System (CMS) Issues in Chapter 6, there are many ways to create duplicate content. For the most part, this does not result from the activities of a spammer, but rather from idiosyncrasies of a website architecture. For this reason, the normal response of the search engines to duplicate content is to filter it out but not penalize the publisher for it in any other way.

They filter it out because they don’t want to show multiple copies of the same piece of content in their search results, as this does not really bring any value to users. They don’t punish the publisher because the great majority of these situations are unintentional.

However, there are three notable exceptions:

- Copyright violations

An actual copyright violation where a publisher is showing a copy of another publisher’s content without permission.

- Thin affiliate sites

A scenario in which the publisher has permission from another publisher, but the content is not unique to them. The common scenario is a site running an affiliate network and generating leads or sales for their clients, largely by offering an affiliate program to other publishers.

The site running the affiliate program generates some content related to the offerings and distributes that to all their affiliates. Then all of these sites publish the exact same (or very similar) content on their websites. The problem the search engines have with this is that they offer very little value as there is nothing unique about their content.

This affiliate site may also create hundreds or thousands of pages to target vertical search terms with little change in content. The classic example of this is creating hundreds of web pages that are identical, except changing the city name referred to on each page (e.g., pages have titles such as “Phoenix Oil Changes,” “Austin Oil Changes,” “Orlando Oil Changes,” etc.).

- Massive duplication

Sites that have a very large amount of duplicate content, even if it is with permission, and it is not a thin affiliate. It is not known what the threshold is, and this probably changes over time, but our experience suggests that sites with 70% or more of their pages as duplicates of other pages on the Web are likely to be subject to a penalty.

There may be other spammy forms of duplicate content not identified here. It is likely to be spam if it is implemented intentionally (e.g., the thin affiliate site example qualifies under this metric), and the content adds no value to the Web.

Especially if you are a novice SEO practitioner/publisher, the first and most important rule is to be familiar with the guidelines of the search engines (see the beginning of this section for the location of the guidelines on the search engine sites).

Second, it is essential that you learn to apply a basic personal filter to your SEO activities. Generally speaking, if you engage in the activity for the sole purpose of influencing search rankings, you are putting your site’s rankings at risk.

For example, if you start buying keyword-rich text links from a bunch of sites across the Web and you do not expect to get significant traffic from these links (enough to justify placing the advertisement), you are headed for trouble.

Search engines do not want publishers/SEO experts to buy links for that purpose. In fact, Google has strongly campaigned against this practice. Google has also invested heavily in paid link detection. The following blog posts are from Matt Cutts, the head of Google’s webspam team:

But there are more ways you can get into trouble other than purchasing keyword-rich text links. Earlier in this chapter we listed a number of ways that spammers behave. Most publishers/SEO practitioners won’t run into the majority of these as they involve extremely manipulative behavior, as we outlined previously in this section. However, novice SEO practitioners do tend to make certain mistakes. Here are some of the more common ones:

Stuffing keywords into your web page so it is unnaturally rich in those words.

Over-optimizing internal links (links on your website to other pages on your website). Generally speaking, this may occur by over-stuffing keywords into the anchor text of those links.

Cloaking, or showing different content to the search engine crawlers than you show to users.

Creating websites with lots of very thin content pages, such as the thin affiliate sites we discussed previously.

Implementing pages that have search-engine-readable text that is invisible to users (hidden text).

Participating in link schemes, such as commenting on others’ blogs or forums for the pure purpose of linking to yourself, participating in link farms, or using other tactics to artificially boost link popularity.

As we discussed previously, there are many other ways to end up in the crosshairs of the search engines, but most of those are the domain of highly manipulative SEO practitioners (sometimes referred to in the industry as black hat SEO practitioners).

Ultimately, you want to look at your intent in pursuing a particular SEO practice. Is it something you would have done if the search engines did not exist? Would it have been part of a publishing and promotional plan for your website in such a world?

This notion of intent is something that the search engines look at very closely when evaluating a site to see whether it is engaging in spamming. In fact, search engine representatives speak about intent (why you did it) and extent (how much did you do it) as being key things they evaluate when conducting a human review of a website.

A perceived high degree of intent and pursuing something to a significant extent is the realm of more severe penalties. Even if your intent is pure and you don’t pursue a proscribed practice to a significant degree, the search engines will want to discount the possible benefits of such behavior from the rankings equation.

For example, if you buy a few dozen links and the search engines figure out that the links are paid for, they will discount those links. This may not be egregious enough for them to penalize you, but they don’t want you to benefit from it either.

The reality is that penalties are imposed on websites. When this happens, it is useful to have an idea how to fix it. So, let’s take a look at how it works.

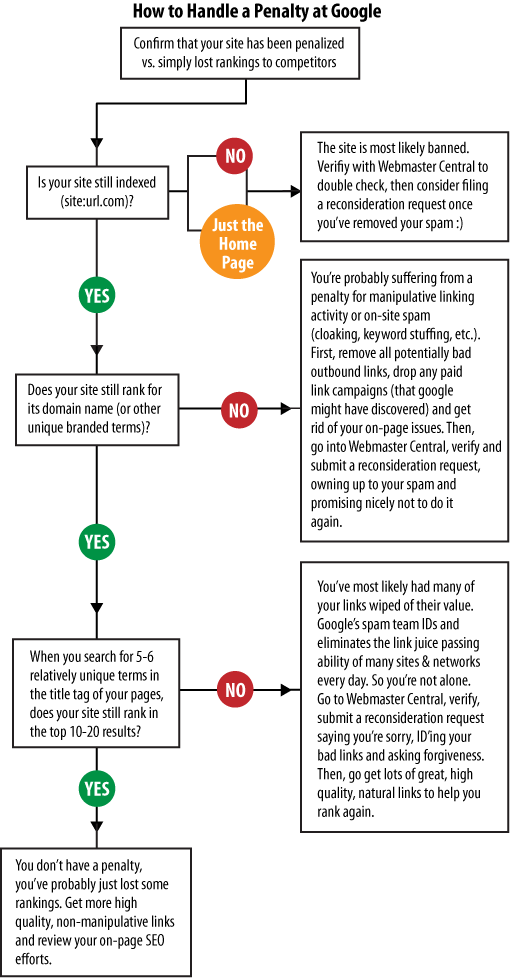

The flowchart in Figure 10-5 shows a series of basic checks that you can use to find out whether you have a problem. It is also important to remember that search engines are constantly tuning their algorithms (Google makes algorithm changes every day). Simple movement up and down in the rankings does not necessarily constitute a penalty.

Getting members of your management team who are not knowledgeable about SEO to understand this can be particularly challenging. Use this chart to help them better understand the difference between a penalty and natural movement in the rankings.

While you’re at it, try to help your management team understand the landscape of search. Search engines make the rules, and since they provide the traffic, publishers have to follow them as best they can. This may not seem fair, but it is the way it works. If you can get a general commitment to follow the rules in your organization, you will have taken a big step forward.

Once you have determined that you are subject to a penalty, there are two major steps you should take to restore your website to full search engine health.

The first step is to fix the problems that caused the penalty. This may not be easy to do if you have engaged in many practices considered manipulative by the search engines or if the violation of the guidelines you have been tagged for was accidental, but getting the penalty removed will not happen until you have fixed the problem.

Once the problems are fixed you can file a reinclusion/reconsideration request. However, we can’t emphasize this enough: if you file such a request without first fixing the problem(s), if you were less than truthful, or if you omitted key facts in your request, you risk burning bridges with the engine and cementing the penalty.

First, your request may be ignored. Second, if you fix the problem and make the request again, that request may fall on deaf ears, in which case your site is more or less doomed.

So now, let’s take a look at the process. The first step is to find the appropriate forms on the search engine’s site. Here is where to find them:

Go to Google Webmaster Tools (https://www.google.com/webmasters/tools), click on the Tools link, and then click the “Submit a reconsideration request” link.

- Yahoo

The Yahoo! reinclusion request form (http://help.yahoo.com/l/us/yahoo/search/search_rereview_feedback.html) also provides a way to request a review of a penalty on your site. Fill out all the required fields and click Submit.

- Bing

Go to Bing Webmaster Tools (http://www.bing.com/webmaster), go to the Bing Site Owner support form, fill in the required information, and indicate that this is a reinclusion request.

Here are the four basics of a reconsideration request, regardless of the engine:

Understand the context of the situation with complete clarity. Search engines get a large number of these requests every day, and their point of view is that you violated their guidelines. You are asking for help from someone who has every right to be suspicious of you.

Clearly define what you did wrong that led (to the best of your knowledge) to your site being banned or penalized.

Demonstrate that you have corrected the issue(s).

Provide assurances that it won’t happen again. If you used an SEO firm that made the transgressions, make it clear that the firm is no longer working with you. If you did it yourself, be very contrite, and state that you now understand the right things to do.

Equally important is to have a clear idea of things you should not put into your reconsideration request:

Do not use reconsideration request forms to request a diagnosis of why your site was banned. It will never happen. They get way too many of these per day.

Don’t whine about how much this is costing you. This is not material to their decision-making process, and it can irritate them. Remember that you need their goodwill.

Do not compare their results with those of another search engine (in either traffic or rankings) to point out that something must be wrong. Search engine algorithms differ greatly, and the results you get will too.

Don’t mention how much you spend on advertising with that search engine. Search engines endeavor to keep their ranking teams separate from their advertising teams. Mentioning a large advertising spend will not help and can backfire if the request is interpreted as a request for special treatment.

Do not submit a reconsideration request unless you are penalized, as we outlined previously.

The bottom line is to be succinct. Keep it short, crisp, and to the point. Research all of your current and past SEO activities to see which ones could be construed as an offense to the search engine’s guidelines prior to any submission of a reconsideration request. You do not want to have the engineer look at the site and decide not to take action because you did not address every issue, because when you send in a second request, it will be that much harder to get their attention.

You should also be aware that you will probably never get a response, other than perhaps an automated one. If you have done your job well and have explained the situation well, you may just find your site back in the index one day.