The concept of using links as a way to measure a site’s importance was first made popular by Google with the implementation of its PageRank algorithm (others had previously written about it, but Google’s rapidly increasing user base popularized it). In simple terms, each link to a web page is a vote for that page, and the page with the most votes wins.

The key to this concept is the notion that links represent an “editorial endorsement” of a web document. Search engines rely heavily on editorial votes. However, as publishers learned about the power of links, some publishers started to manipulate links through a variety of methods. This created situations in which the intent of the link was not editorial in nature, and led to many algorithm enhancements, which we will discuss in this chapter.

To help you understand the origins of link algorithms, the underlying logic of which is still in force today, let’s take a look at the original PageRank algorithm in detail.

The PageRank algorithm was built on the basis of the original PageRank thesis authored by Sergey Brin and Larry Page while they were undergraduates at Stanford University.

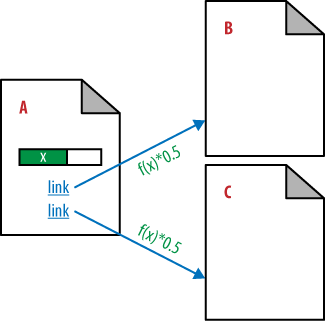

In the simplest terms, the paper states that each link to a web page is a vote for that page. However, votes do not have equal weight. So that you can better understand how this works, we’ll explain the PageRank algorithm at a high level. First, all pages are given an innate but tiny amount of PageRank, as shown in Figure 7-1.

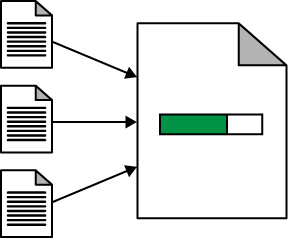

Pages can then increase their PageRank by receiving links from other pages, as shown in Figure 7-2.

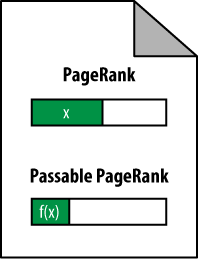

How much PageRank can a page pass on to other pages through links? That ends up being less than the page’s PageRank. In Figure 7-3 this is represented by f(x), meaning that the passable PageRank is a function of x, the total PageRank.

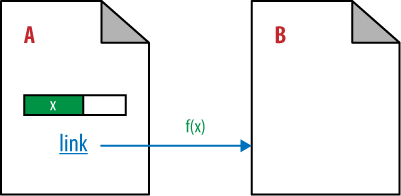

If this page links to only one other page, it passes all of its PageRank to that page, as shown in Figure 7-4, where Page B receives all of the passable PageRank of Page A.

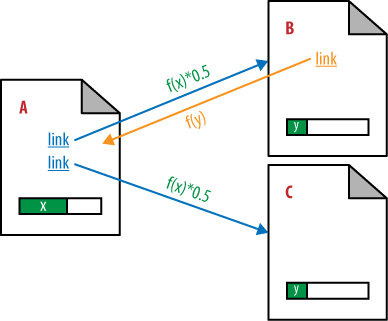

However, the scenario gets more complicated because pages will link to more than one other page. When that happens the passable PageRank gets divided among all the pages receiving links. We show that in Figure 7-5, where Page B and Page C each receive half of the passable PageRank of Page A.

In the original PageRank formula, link weight is divided equally among the number of links on a page. This undoubtedly does not hold true today, but it is still valuable in understanding the original intent. Now take a look at Figure 7-6, which depicts a more complex example that shows PageRank flowing back and forth between pages that link to one another.

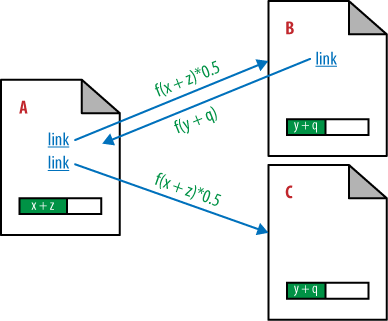

Cross-linking makes the PageRank calculation much more complex. In Figure 7-6, Page B now links back to Page A and passes some PageRank, f(y), back to Page A. Figure 7-7 should give you a better understanding of how this affects the PageRank of all the pages.

The key observation here is that when Page B links to Page A to make the link reciprocal, the PageRank of Page A (x) becomes dependent on f(y), the passable PageRank of Page B, which happens to be dependent on f(x)!. In addition, the PageRank that Page A passes to Page C is also impacted by the link from Page B to Page A. This makes for a very complicated situation where the calculation of the PageRank of each page on the Web must be determined by recursive analysis.

We have defined new parameters to represent this: q, which is the PageRank that accrues to Page B from the link that it has from Page A (after all the iterative calculations are complete); and z, which is the PageRank that accrues to Page A from the link that it has from Page B (again, after all iterations are complete).

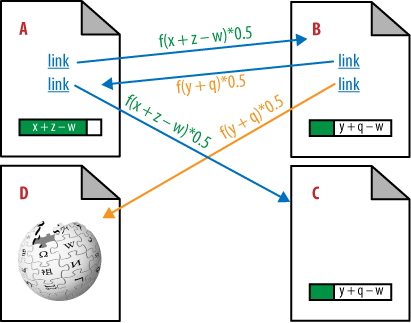

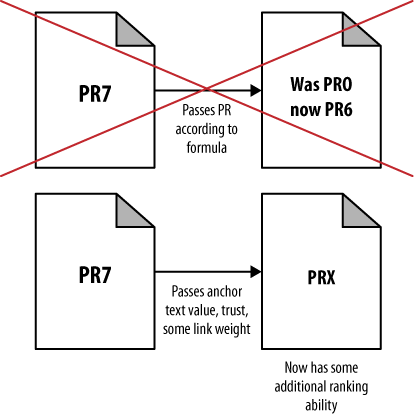

The scenario in Figure 7-8 adds additional complexity by introducing a link from Page B to Page D. In this example, pages A, B, and C are internal links on one domain, and Page D represents a different site (shown as Wikipedia). In the original PageRank formula, internal and external links passed PageRank in exactly the same way. This became exposed as a flaw because publishers started to realize that links to other sites were “leaking” PageRank away from their own site, as you can see in Figure 7-8.

Because Page B links to Wikipedia, some of the passable PageRank is sent there, instead of to the other pages that Page B is linking to (Page A in our example). In Figure 7-8, we represent that with the parameter w, which is the PageRank not sent to Page A because of the link to Page D.

The PageRank “leak” concept presented a fundamental flaw in the algorithm once it became public. Like Pandora’s Box, once those who were creating pages to rank at Google investigated PageRank’s founding principles, they would realize that linking out from their own sites would cause more harm than good. If a great number of websites adopted this philosophy, it could negatively impact the “links as votes” concept and actually damage Google’s potential. Needless to say, Google corrected this flaw to its algorithm. As a result of these changes, worrying about PageRank leaks is not recommended. Quality sites should link to other relevant quality pages around the Web.

Even after these changes, internal links from pages still pass some PageRank, so they still have value, as shown in Figure 7-9.

Google has changed and refined the PageRank algorithm many times. However, familiarity and comfort with the original algorithm is certainly beneficial to those who practice optimization of Google results.

Classic PageRank isn’t the only factor that influences the value of a link. In the following subsections, we discuss some additional factors that influence the value a link passes.

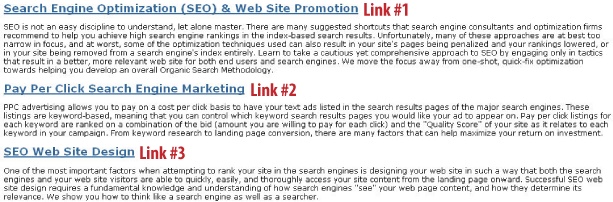

Anchor text refers to the clickable part of a link from one web page to another. As an example, Figure 7-10 shows a snapshot of a part of the Alchemist Media Home Page at http://www.alchemistmedia.com.

The anchor text for Link #3 in Figure 7-10 is “SEO Web Site Design”. The search engine uses this anchor text to help it understand what the page receiving the link is about. As a result, the search engine will interpret Link #3 as saying that the page receiving the link is about “SEO Web Site Design”.

The impact of anchor text can be quite powerful. For example, if you link to a web page that has no search-engine-visible content (perhaps it is an all-Flash site), the search engine will still look for signals to determine what the page is about. Inbound anchor text becomes the primary driver in determining the relevance of a page in that scenario.

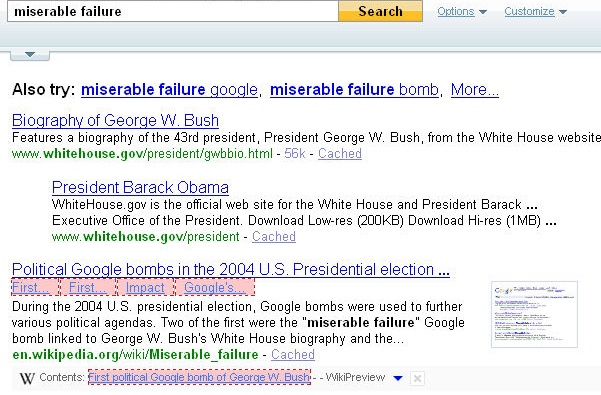

The power of anchor text also resulted in SEOs engaging in Google Bombing. The idea is that if you link to a given web page from many places with the same anchor text, you can get that page to rank for queries related to that anchor text, even if the page is unrelated.

One notorious Google Bomb was a campaign that targeted the Whitehouse.gov biography page for George W. Bush with the anchor text miserable failure. As a result, that page ranked #1 for searches on miserable failure until Google tweaked its algorithm to reduce the effectiveness of this practice.

However, this still continues to work in Yahoo! Search (as of May 2009), as shown in Figure 7-11.

President Obama has crept in here too, largely because of a redirect put in place by the White House’s web development team.

Links that originate from sites/pages on the same topic as the publisher’s site, or on a closely related topic, are worth more than links that come from a site on an unrelated topic.

Think of the relevance of each link being evaluated in the specific context of the search query a user has just entered. So, if the user enters used cars in Phoenix and the publisher has a link to the Phoenix used cars page that is from the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce, that link will reinforce the search engine’s belief that the page really does relate to Phoenix.

Similarly, if a publisher has another link from a magazine site that has done a review of used car websites, this will reinforce the notion that the site should be considered a used car site. Taken in combination, these two links could be powerful in helping the publisher rank for “used cars in Phoenix”.

This has been the subject of much research. One of the more famous papers, written by Apostolos Gerasoulis and others at Rutgers University and titled “DiscoWeb: Applying Link Analysis to Web Search” (http://www.cse.lehigh.edu/~brian/pubs/1999/www8/), became the basis of the Teoma algorithm, which was later acquired by AskJeeves and became part of the Ask algorithm.

What made this unique was the focus on evaluating links on the basis of their relevance to the linked page. Google’s original PageRank algorithm did not incorporate the notion of topical relevance, and although Google’s algorithm clearly does do this today, Teoma was in fact the first to offer a commercial implementation of link relevance.

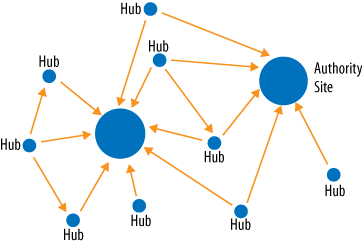

Teoma introduced the notion of hubs, which are sites that link to most of the important sites relevant to a particular topic, and authorities, which are sites that are linked to by most of the sites relevant to a particular topic.

The key concept here is that each topic area that a user can search on will have authority sites specific to that topic area. The authority sites for used cars are different from the authority sites for baseball.

Refer to Figure 7-12 to get a sense of the difference between hub and authority sites.

So, if the publisher has a site about used cars, it seeks links from websites that the search engines consider to be authorities on used cars (or perhaps more broadly, on cars). However, the search engines will not tell you which sites they consider authoritative—making the publisher’s job that much more difficult.

The model of organizing the Web into topical communities and pinpointing the hubs and authorities is an important model to understand (read more about it in Mike Grehan’s paper, “Filthy Linking Rich!” at http://www.search-engine-book.co.uk/filthy_linking_rich.pdf). The best link builders understand this model and leverage it to their benefit.

Trust is distinct from authority. Authority, on its own, doesn’t sufficiently take into account whether the linking page or the domain is easy or difficult for spammers to infiltrate. Trust, on the other hand, does.

Evaluating the trust of a website likely involves reviewing its link neighborhood to see what other trusted sites link to it. More links from other trusted sites would convey more trust.

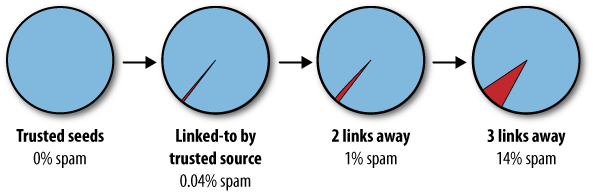

In 2004, Yahoo! and Stanford University published a paper titled “Combating Web Spam with TrustRank” (http://www.vldb.org/conf/2004/RS15P3.PDF). The paper proposed starting with a trusted seed set of pages (selected by manual human review) to perform PageRank analysis, instead of a random set of pages as was called for in the original PageRank thesis.

Using this tactic removes the inherent risk in using a purely algorithmic approach to determining the trust of a site, and potentially coming up with false positives/negatives.

The trust level of a site would be based on how many clicks away it is from seed sites. A site that is one click away accrues a lot of trust; two clicks away, a bit less; three clicks away, even less; and so forth. Figure 7-13 illustrates the concept of TrustRank.

The researchers of the TrustRank paper also authored a paper describing the concept of spam mass (http://ilpubs.stanford.edu:8090/697/1/2005-33.pdf). This paper focuses on evaluating the effect of spammy links on a site’s (unadjusted) rankings. The greater the impact of those links, the more likely the site itself is spam. A large percentage of a site’s links being purchased is seen as a spam indicator as well. You can also consider the notion of reverse TrustRank, where linking to spammy sites will lower a site’s TrustRank.

It is likely that Google, Yahoo!, and Bing all use some form of trust measurement to evaluate websites, and that this trust metric can be a significant factor in rankings. For SEO practitioners, getting measurements of trust can be difficult. Currently, mozTrust from SEOmoz’s Linkscape is the only publicly available measured estimation of a page’s TrustRank.

The search engines use links primarily to discover web pages, and to count the links as votes for those web pages. But how do they use this information once they acquire it? Let’s take a look:

- Index inclusion

Search engines need to decide what pages to include in their index. Discovering pages by crawling the Web (following links) is one way they discover web pages (the other is through the use of XML Sitemap files). In addition, the search engines do not include pages that they deem to be of low value because cluttering their index with those pages will not lead to a good experience for their users. The cumulative link value, or link juice, of a page is a factor in making that decision.

- Crawl rate/frequency

Search engine spiders go out and crawl a portion of the Web every day. This is no small task, and it starts with deciding where to begin and where to go. Google has publicly indicated that it starts its crawl in PageRank order. In other words, it crawls PageRank 10 sites first, PageRank 9 sites next, and so on. Higher PageRank sites also get crawled more deeply than other sites. It is likely that other search engines start their crawl with the most important sites first as well.

This would make sense, because changes on the most important sites are the ones the search engines want to discover first. In addition, if a very important site links to a new resource for the first time, the search engines tend to place a lot of trust in that link and want to factor the new link (vote) into their algorithms quickly.

- Ranking

Links play a critical role in ranking. For example, consider two sites where the on-page content is equally relevant to a given topic. Perhaps they are the shopping sites Amazon.com and (the less popular) JoesShoppingSite.com.

The search engine needs a way to decide who comes out on top: Amazon or Joe. This is where links come in. Links cast the deciding vote. If more sites, and more important sites, link to it, it must be more important, so Amazon wins.