2. Sizing Up Subprime

Imagining how something as obscure as a subprime mortgage loan could have brought the global financial system to its knees and pushed the U.S. economy into a deep recession might be hard. It’s particularly strange because such loans, designed for people with a dark mark on their credit records, were, at most, marginal financial products for most of their quarter-century history.

Yet the word subprime has come to stand for something much bigger: an unprecedented, broad-based erosion of credit standards. During the subprime lending frenzy, practically anyone could get a mortgage. Loans were streamlined, stripped of most controls, and offered freely under conditions that would have given most traditional bankers nightmares. Lenders even handed checks to people without requiring proof that they had a job or the income necessary to pay back the loan. The subprime phenomenon grew far beyond home mortgages, to include auto loans, credit cards, and even student loans.

Despite the clear risks, lenders also no longer required borrowers to obtain mortgage insurance. Such insurance used to be required of anyone attempting to buy a home without a substantial down payment. Instead, lenders advised borrowers to skirt the insurance requirement by taking out two loans: a first mortgage small enough not to need insurance, and a second to cover the rest of the purchase price. The borrowers’ incentives were clear: Payments on the second mortgage were less than the insurance—at least for awhile.

A requirement that borrowers save for the expenses of home ownership also fell by the wayside. Lenders no longer required an escrow account for property taxes, which were rapidly escalating with housing values. The same applied to homeowners’ insurance, which was growing more expensive, particularly in storm-prone coastal areas.

Mortgages grew more complex, evolving from plain-vanilla fixed-rate loans into myriad adjustable-rate and variable-payment form loans. Adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) that included only interest in the monthly payments—even loans in which such payments didn’t cover the interest, with the difference added back to the principal—became increasingly common. Only someone adept at financial planning and spreadsheets could reasonably map out what these loans meant for a homeowner’s future mortgage bill.

Examining the terms under which home buyers were able to get loans in the housing boom is essential to understanding why so many are now losing their homes. The smorgasbord of terms offered to borrowers during the boom is confusing but necessary to sort through.

Government Versus Private

The menu of mortgages available to home buyers begins with those the government offers. The government plays a surprisingly large role in the nation’s housing market; more than 40% of all mortgage loans outstanding have some form of federal backing.1

Washington supports mortgage lending most directly through the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Veterans Administration (VA).2 These agencies don’t make loans themselves; they insure lenders against default. In exchange, the agencies impose some modest standards covering down payments, income, and other conditions. Despite the easy terms, FHA and VA lending faded to a trickle during the housing boom, as private subprime lenders offered borrowers much more attractive terms. More recently, the agencies have made a comeback as subprime lending has evaporated and as policymakers have expanded the FHA’s lending authority.

Government’s role in the housing market is also evident in its relationship with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae, for short) was established during the Great Depression to improve the flow of mortgage credit and increase home ownership. The Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corp. (Freddie Mac) was set up in 1970 to do essentially the same thing: to provide competition to Fannie Mae. Both were subsequently so successful that they were spun into publicly traded companies in 1989.

The two were still heavily regulated, and their charters required them to promote home ownership among lower-income and disadvantaged groups. As such, they were barred from backing very large or “jumbo” loans. Loans that fall below a certain size (the largest currently being $729,000 in the nation’s highest-priced markets) and that also conform to other Fannie and Freddie requirements are known as “conforming” loans.

The government no longer formally backed Fannie and Freddie and had no legal obligation to help if they stumbled. Investors firmly believed that if push came to shove, Washington would be there if needed—so much so that Fannie and Freddie were able to raise funds more cheaply than other private financial institutions. As is clear from recent events, investors were right that the federal government would not let either company go down. Fannie and Freddie had become two of the largest global financial institutions and were so important to the U.S. housing market and economy that they were too big to fail.

Fannie and Freddie came full circle when, in early September 2008, the Bush Administration determined that they were headed toward insolvency and put them into conservatorship. That is, the government took control of the institutions, effectively wiping out the company’s shareholders.

Fannie and Freddie were not key drivers of the subprime frenzy, but they did participate in it. They couldn’t help themselves from investing in riskier mortgage loans, partly because of their need to generate profits for their shareholders and partly because of their charters, which required that they provide mortgage credit to borrowers that subprime lenders were taking from them. Even though Fannie and Freddie suffered modest losses on their mortgage investments (at least, compared to other mortgage lenders), the losses were large enough to overwhelm their capital. Policymakers felt they had no choice but to take them over; allowing them to fail was just not an option. The FHA, Fannie Mae, and Freddie Mac—all part of the federal government—now account for most of the nation’s mortgage lending.

Prime Versus Subprime

Government’s role in the mortgage market rapidly diminished during the height of the housing boom and bubble. At its peak in 2007, private sources of mortgage credit overtook government sources of mortgage credit and accounted for some 60% of outstanding mortgage debt.

The private mortgage market can be sliced in numerous ways. The most obvious is based on borrowers’ credit scores. The market distinguishes between prime and subprime borrowers using such scores, which reflect how an individual has managed his debts in the past. Scores are derived using statistical techniques based on information in borrowers’ credit files. Borrowers with a record of late debt payments receive a lower score. Borrowers with a lot of credit cards and other financial obligations receive lower scores, as do borrowers who actively use most of the credit lines available to them.

Many types of credit scores exist—almost as many as there are lenders—but the most common is the FICO score, named after the firm, which was the first to successfully commercialize its use. The FICO3 score ranges from a low of 300 to a perfect 850. The lower the score, the higher the likelihood that the borrower will not manage new credit well. Until recent years, credit scores were primarily used to make decisions about credit cards. In the past decade, however, scoring has become common across all consumer lending, including mortgage loans.

As the term suggests, a prime borrower is someone lenders are eager to do business with because the person has a good history of debt repayment. Prime borrowers might have missed a payment or two in the past, but never by more than a month. A bill two months past due causes borrowers’ credit scores to drop, jeopardizing their prime status. By contrast, a subprime borrower has a significantly blemished credit history, or none at all. During the housing boom, many first-time home buyers had never received credit.

A wide range of in-betweens exists—not quite prime, not quite subprime. Some of these borrowers receive labels such as “alternative-A,” or eligible for an A or prime loan, but with something not quite right. These alt-A borrowers generally have solid credit scores, but another credit issue precludes them from being considered prime. For example, an investor or borrower whose income has not been documented and verified might be classified as alt-A.

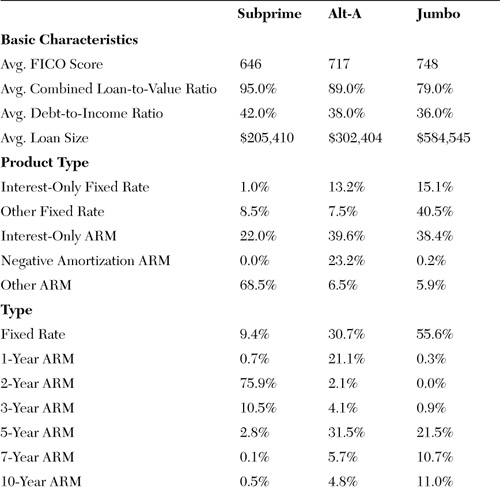

No credit score officially distinguishes a prime borrower from a subprime borrower, but most lenders and regulators consider someone with a score of less than 620 subprime. (The average national credit score across all borrowers is about 700.) Credit scores for subprime borrowers moved higher during the housing boom, but largely because lenders were aggressively pushing subprime loans—loans that carried higher rates and fees—to people who might well have been eligible for cheaper conventional mortgages. The average FICO score among subprime borrowers who took out loans to purchase homes in 2006 had risen to about 650 (see Table 2.1).

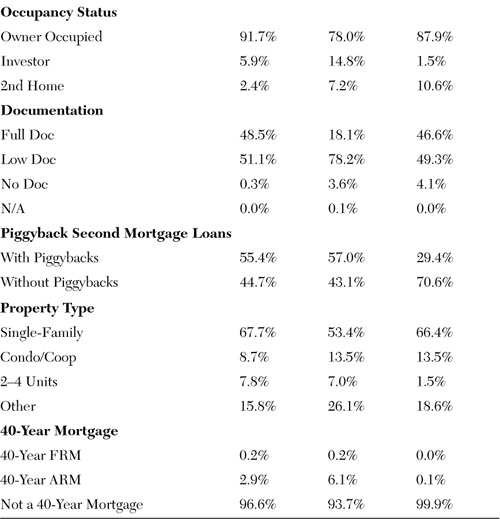

Table 2.1 What Is a Subprime Mortgage? Characteristics of Securitized Mortgage Purchase Loans, 2006

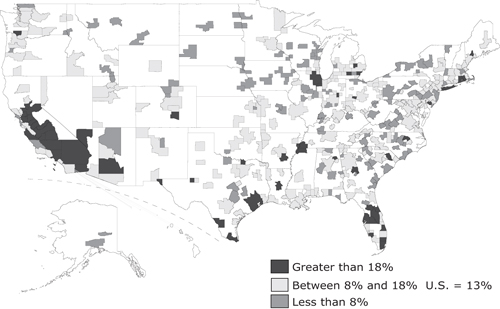

Subprime lending took off everywhere across the country, but ground zero was in California and Florida. More than one-third of the loans made in 2006 in the Central Valley of California and throughout south Florida were subprime (see Figure 2.1).4 The border areas of Texas and those around Detroit were also hotbeds of such lending. Subprime was less prevalent in areas where credit scores were higher, such as New England and much of the farm belt. The lowest average credit scores in the country are along the Texas–Mexican border; Wisconsin households have the highest credit scores in the nation.5

Figure 2.1 Where is subprime? Subprime share of mortgage debt outstanding, 2007q4.

Fixed Versus Adjustable

Subprime borrowers’ financial woes were worsened by the fact that most took out adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs). ARMs have existed for a quarter-century, but lenders historically have offered them only to home buyers with good credit, bigger down payments, and stable incomes. This changed quickly during the housing boom; 90% of subprime loans made in 2006 carried adjustable rates.

The fixed-rate mortgage loan, in which monthly mortgage payments never change, no matter what happens to interest rates or financial markets, is a uniquely American financial instrument. It is the predominant type of mortgage, accounting for three-fourths of mortgage debt outstanding. Thirty-year, fixed-rate loans were born in the wake of the Great Depression and fostered by the federal government, via the FHA and Fannie Mae, as a way to promote home ownership.

Fixed-rate mortgages have succeeded in putting and keeping households in their homes. Households with fixed mortgages can accurately budget their housing costs, making payment problems unusual. When long-term interest rates decline (fixed mortgage rates are commonly pegged to the rates on ten-year U.S. Treasury bonds), borrowers can easily and cheaply refinance at the lower rate.

Fixed-rate loans have obvious advantages for borrowers, but they can be unaffordable when inflation and interest rates are high. ARMs were developed in the early 1980s, a period of double-digit inflation and interest rates, to help with these affordability problems. Lenders can offer borrowers lower rates to start, pegging the interest rate to short-term market rates, which are generally lower than long-term rates. Borrowers don’t know for sure what their future mortgage payments will be, but they accept the greater uncertainty in exchange for an initially more affordable mortgage.

Policymakers have also encouraged the use of ARMs over the years. During the 1980s, regulators viewed ARMs as a way for lending institutions to reduce some of the interest-rate risk they continually struggle with. The savings and loan crisis of the early 1990s grew out of the mismatch between the fluctuating interest rates savings depositors demanded and the fixed interest payments S&Ls received on the mortgages they held. Regulators believed ARMs would help solve lenders’ problems matching their borrowing costs with their interest income on their loans.

Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan <$IGreenspan, Alan>was still singing the praises of ARM loans as recently as this decade. Greenspan argued that most people remain in their homes less than ten years, so why should they pay the added interest expense associated with a fixed-rate loan based on a ten-year bond? ARM loans that adjusted after three, five, or even seven years would be cheaper and fit better with American families’ lifestyles.

Yet ARM loans also shift substantial risk to borrowers when rates fluctuate. Falling short-term rates are not a problem for borrowers, but rising rates can quickly create a major financial headache. Indeed, homeowners with ARM loans are much more likely to have credit problems than those with fixed-rate loans. Even in the best of times, the delinquency rate on ARM loans is 50% greater than on fixed-rate loans.6

The fact that most subprime and alt-A loans made in the housing boom were ARMs is disconcerting. ARMs account for a fourth of total mortgage debt outstanding, but they make up three-quarters of subprime loans and almost two-thirds of alt-A loans. Most subprime ARM loans are designed to “reset” after two years. That is, their interest rates remain fixed for the first 24 months; after that, the monthly payment is tied to a benchmark index. Payments generally adjust every six months. The bulk of subprime loans made in 2006 began to reset in early 2008.

The size of a reset depends on prevailing interest rates. Homeowners who took out ARMs in 2005 saw their payments soar in 2007 because short-term rates were very high early that year. Most subprime loans have an adjustment cap of 2 percentage points, meaning that the rate can’t reset by more than that. In early 2007, many ARM loans hit the cap. Monthly payments on these loans jumped by an average of $350, taking the average homeowner’s monthly payment from $1,200 to $1,550.

In a quest to improve affordability, lenders heavily marketed ARM loans with features that shifted even more interest-rate risk to borrowers. One such feature was the “teaser” rate, an extraordinarily low initial rate designed to enable borrowers to qualify for a loan. At times, teasers were offered at rates of only 1% or 2%. Borrowers qualified for loans based on the monthly payments implied by the low teasers, even though the payments would rise substantially when the ARM began to reset. That was a problem for another day.

“Interest-only” and “option” ARMs also became popular ways to arrange low initial monthly payments. Interest-only ARMs allow borrowers to forgo principal payments. Option ARMs give borrowers a choice; they can make standard interest and principal payments, pay only the interest, or pay only a minimum amount that doesn’t even cover the interest due. Interest not paid is added back into the loan principal. This is known as negative amortization, a reverse of the way most mortgage loans behave. Most loans self-amortize over their life, typically 30 years. Not surprisingly, most borrowers who take out option ARMs use the negative-amortization payment option.

Interest-only and option ARMs are very effective ways to significantly lower monthly payments early on, but they impose much higher borrowing costs in the future. The larger the amount of negative amortization and the longer the period over which it occurs, the larger the increase in the payment needed later to fully amortize the loan.

In the teeth of the housing boom, teaser rates on subprime loans were common. Interest-only loans grew in use. Option ARM loans had not yet become common for subprime borrowers, although lenders were beginning to consider them. Yet the housing and mortgage markets unraveled before they had a chance.

Risk Layering

With so many borrowers with sketchy credit getting increasingly complex ARMs, a growing number faced difficulty staying current on their loans. Yet for millions to actually begin losing their homes, something else had to be at work. Credit risk managers call that something else “risk layering.” This was the combination of subprime borrowers and their unmanageable ARMs with little or no down payment, unverified and thus unreliable incomes, and already burdensome debt loads.

Down payments were the first traditional lending standard to crumble. For many potential borrowers, the principal impediment to purchasing a home was saving that initial stake. Typically at least 20% of the purchase price, the down payment represented the owners’ equity, their stake in the home. The down payment was large enough to convince lenders that a new owner was truly committed and would not risk losing the investment. This standard steadily eroded. Down payments shrank to 10% and then 5%; in the midst of the housing boom, many subprime borrowers were putting down little, if anything.

To compensate for a low down payment, borrowers in the past had been required to purchase mortgage insurance. Without much of a financial stake in the home, a borrower was more likely to default; insurance was necessary to cover the lender and pay any associated costs in a foreclosure. This insurance was costly, however, so creative lenders came up with an alternative: Take out two loans. Buyers could obtain a first mortgage equal to 80% of the home’s purchase price, and a second mortgage that covered the remaining 20%. These so-called “piggyback” second loans, which usually took the form of home equity lines of credit, were cheap, particularly when the Federal Reserve Board was easing monetary policy. Rates on most home equity lines were linked to short-term lending rates, as opposed to longer-term (and usually higher) rates that governed standard home mortgages.

Putting a piggyback loan on top of a standard mortgage was a very sweet deal for a home buyer. To have a house of your own, you needed little or no money; all you had to do was sign some papers. Essentially all the money paid to the seller of a house was borrowed. For lenders, however, this was an exceptionally risky proposition. Before the housing bubble, the average American homeowner’s mortgage debt equaled 40% of the home’s purchase price. Excluding families that already had paid off their mortgages, the average U.S. mortgage still equaled only 65% of a home’s market price. But by 2006, the average subprime borrower had mortgage debt equal to 95% of the home’s purchase price. That was a recipe for disaster: If home prices fell, many of those homeowners would owe more on their loans than their homes were worth. That’s exactly what happened.

Most homeowners will work to make good on their mortgage even in tough circumstances. If they also have to struggle with a substantial increase in their mortgage payment or a disruption to their income, however, they will find it all but impossible to keep the house. If, in addition, their own equity stake in the house is gone—because the amount they owe on their mortgages exceeds the market value of the home, putting it “under water,” in the parlance of the trade—they might easily lose hope and simply decide to walk away.

Not only did lenders stop asking for down payments, but they also stopped asking for proof of income. Asking for a W-2 form or a tax return had always been a standard part of making a loan. In some cases, a self-employed borrower didn’t have the necessary documentation, but they were uncommon, and lenders had enough other information to feel comfortable that the borrower could support the loan. This changed during the boom. Lenders stopped asking for proof of income altogether. By 2006, well over half of subprime loans were so-called “stated income” loans; the borrower simply stated the income, and the lender accepted that number. Some borrowers lied outright, and many more stretched the truth to stretch into a mortgage.

In most cases, the mortgage they stretched into put a heavy burden on their stated income, even at the teaser ARM rate. The average recipient of a subprime mortgage in 2006 was committing more than 40% of her income to mortgage payments. Of course, most borrowers had liabilities beyond their mortgages. Staying current on credit cards, auto loans, student loans, and other debts required more than half these borrowers’ incomes.

Alt-A and jumbo borrowers weren’t quite as layered up, but they weren’t far behind. In 2006, for example, nearly 15% of alt-A borrowers were investors; they bought a house not to live in, but to sell quickly at a profit. These buyers were much more likely to walk away from a bad mortgage deal.

To Securitize or Not to Securitize

To fully understand a subprime mortgage, you need to know how it is financed. Fundamentally, loans either are financed directly by financial institutions such as commercial banks and thrift institutions, or are repackaged as bonds (that is, securitized) and sold to investors, who keep or trade them in global financial markets. The overwhelming majority of subprime loans have been securitized.

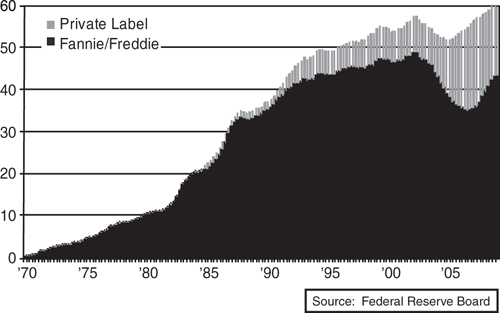

A quarter-century ago, most mortgage loans were funded the old-fashioned way: Commercial banks or savings and loans loaned the money they had received from depositors. Only a tenth of mortgage loans were securitized, and the securities market was dominated entirely by the government-related agencies Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and Ginnie Mae, the agency that insures mortgage securities backed by FHA and VA loans (see Figure 2.2).

Figure 2.2 Securitization flourishes: share of mortgage debt that is securitized.

This all changed during the 1980s and 1990s. Securitization flourished, partly because the S&L industry had all but collapsed. That collapse, in turn, can be traced to how S&Ls had mismanaged the fixed-rate mortgage loans they originated. Meanwhile, Fannie and Freddie were flourishing. Both had become publicly traded companies in the late 1980s; the move unfettered them from the government but did not take away the advantage they enjoyed as “government-sponsored enterprises.” Both were able to raise money cheaply from investors who assumed they were safer than other banks. As a result, both grew rapidly in size and scope. By the mid-1990s, more than half of all mortgage loans had been securitized.

The securities market also underwent a substantial transformation beginning in the 1990s, when private financial institutions (mainly investment banks) became substantial players. Fannie and Freddie were barred from making subprime, alt-A, and jumbo loan business, so these other institutions moved in, expanding these markets as well. At the peak of activity, just before the subprime shock, these private-label securities financed one-fifth of all mortgage loans.

The benefits of securitization appeared substantial. For institutions that originated loans (commercial banks, but also nonbank mortgage lenders and others), securitization reduced their risk and freed up cash for additional lending. For global investors, it provided an opportunity to invest in a much broader array of assets and to precisely calibrate the amount of risk in their portfolios. Wall Street loved the hefty fees involved in packaging and selling the securities. Policymakers also liked securitization because it appeared to spread risk broadly among global investors.

By mid-2008, as the effects of the subprime shock spread, mortgage lending seemed to have gone full circle. Private-label securitization had collapsed, and banks, S&Ls, and the agencies were trying to fill the void. The volume of mortgage securities issued by Fannie, Freddie, and Ginnie Mae was slowly reviving. And while banks and thrifts weren’t making subprime and alt-A loans, they were beginning to make prime jumbo loans.7 How this trend developed became critical in determining when and how quickly the U.S. housing market revived.

Sizing Subprime

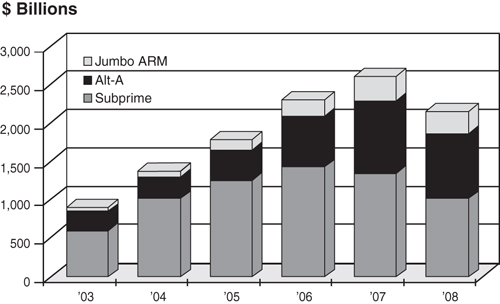

The home sales and mortgage lending craze lasted from spring 2004 to fall 2007. Throughout this period, the market was flooded with the riskiest varieties of subprime, alt-A, and jumbo ARM loans, the types of loans lenders would have been too nervous to make even a few years before.

The frenzied lending hit an apex in 2006. Of the $3 trillion in loans extended to all mortgage borrowers that year, $615 billion were subprime, $475 billion were alt-A, and $395 billion were jumbo ARMs. An incredible $250 billion in the riskiest stated-income, no-down-payment subprime ARM loans were originated.

In truth, barely anyone expected these loans to be around very long. The expectation was not that they would default, but that they would be refinanced before trouble hit. The thinking was that house prices would continue to rise strongly, creating new wealth in the form of housing equity for even borrowers who had put down no money. This equity would be enough to convince future lenders to replace the existing loan with a new one, with possibly even better terms for the borrower.

House prices peaked just as lending was at its most crazed, in spring 2006, and then began to fall. By early 2009, they were back to levels that had prevailed in mid-2003. That left most subprime borrowers who had received loans with little or no down payment during the boom in a dangerous situation, owing much more than their properties were worth. Refinancing was no longer an option because a new loan could not be enough to pay off the old one.

Fourteen million American homeowners, more than one-fourth of all mortgage holders, are now in this untenable financial situation. The face value of their mortgages is a whopping $2.5 trillion, equal to nearly a quarter of all mortgage debt outstanding. Most of this, some $2 trillion, consists of subprime, alt-A, and jumbo ARM debt; the remaining $500 billion is among prime conforming borrowers (see Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3 Lots of subprime: mortgage debt outstanding.

Given the millions of homeowners and trillions of dollars involved, it was perhaps inevitable that the global financial system would react. But what happened next was bigger than anyone had foreseen.