8. Home Builders Run Aground

Home building is a cyclical business. Few other industries experience the same roller-coaster ride in demand and price. As clear as this seems in retrospect, it was far from conventional wisdom during the housing boom. For an unprecedented 15 years, beginning in the early 1990s and lasting until the boom’s peak in 2005, home building posted steady annual growth in activity, sales, and profits. Even during the 2001 recession, the industry’s ascent was interrupted only briefly.

The home-building industry seemed to have gotten its act together in the 1990s. From a fragmented collection of small, privately held and essentially local builders, each putting up a few dozen homes a year, the industry had transformed itself, becoming dominated by a dozen publicly traded national firms that built thousands of homes annually. In 1990, fewer than one in ten U.S. homes was built by a publicly held firm; by 2005, the proportion was nearly one in three.

The industry’s consolidation had been driven by the cost savings that came with scale. Everything from lumber to dry wall was cheaper in bulk. More important than materials, however, was the big builders’ ability to acquire large tracts of the most attractive land in the nation’s most lucrative housing markets. Because of their heft, large firms were better able to navigate the labyrinth of zoning and permitting restrictions thrown up in many places to thwart development. Builders with large national operations were also more likely to withstand the kinds of regional economic downturns that had done in many of their smaller competitors.

In theory, publicly traded builders’ advantages included more and better information about their customers and markets. They had the resources to precisely gauge the demand for their product and what the competition was up to; therefore, they were less likely to make a serious business misstep. Small builders knew their communities, but they had little understanding of the broader economic and demographic forces shaping demand and supply for homes—a vital tool for success in such a sensitive business.

Shareholders and the global capital markets were also expected to impose discipline on the large construction firms, improving their performance. The smart money, it was believed, would ensure that egotistical builders didn’t get carried away and put up more homes than the market could absorb. In the past, many smaller home builders had gotten into trouble erecting homes “on spec”—that is, with no bona fide buyer, only a local banker willing to put up the funds in anticipation of a sale. This sort of trouble wasn’t going to happen again, or so it was thought.

The optimism was misplaced, however. On the contrary, publicly traded builders’ access to freely flowing capital enabled them to put up homes long after housing demand had begun to wane. In the end, builders and their shareholders turned out to be about as good at gauging demand as Silicon Valley’s tech gurus had been during the dotcom craze of the late 1990s. Like tech-company executives, builders had become intoxicated, as well as hugely wealthy, by their own lofty stock prices. Such prices could be justified and sustained only by building and selling more homes at higher prices.

The builders quickly forgot the pain their colleagues in the manufactured housing industry had experienced just a few years earlier. Mobile homes had gone upscale in the mid-1990s; the industry thought it had found a foolproof way to turn lower-income renters into homeowners while attracting older empty-nesters as well. At one point, manufactured housing accounted for an astounding 20% of all residential construction. But those soaring sales did not stem from genuine growth in demand or better product design—they were simply the result of very easy credit. Loans to buy mobile homes were being securitized and sold into global capital markets. Households were happy to borrow the nearly free money—they just weren’t able to repay it. When global investors figured this out, the lending stopped. Without credit, unsold manufactured homes piled up on dealer lots, and the industry has never recovered. It was a sobering tale the home builders knew well; they just figured it didn’t apply to them.

During the decade’s housing boom, builders put up far too many single-family homes and apartments. At its worst, millions of empty units flooded the housing market. Builders were choking on unsold inventory, and investors who had purchased homes couldn’t sell or rent them. There just weren’t enough American households to fill all the vacant homes. And unlike past periods of regional overbuilding, such as in Texas in the mid-1980s, these unsold homes weren’t stick-like structures that could as easily be torn down as sold; they were large and well-appointed residences.

Builders had swallowed their own marketing hype. The industry’s most vocal CEOs argued that demand for new homes would rise strongly ad infinitum, powered by a steady increase in foreign immigrants seeking a first home and aging baby boomers looking for a second one. Builders also had faith that Americans would rather own than rent, and that with low mortgage rates and ample credit, the national rate of homeownership could climb steadily higher. But their logic and arithmetic didn’t add up. Home builders’ enduring optimism, so instrumental in driving past housing cycles, had completely pervaded this one.

As the number of vacant homes mounted through 2006, 2007, and 2008, builders had no choice but to slash construction and house prices. It quickly became a matter of survival, and many builders didn’t make it; bankruptcies and liquidations mounted. The home-building cycle, which had powered the broader economy during the boom, cost it dearly in the bust. During the first half of the 2000s, rising home construction alone accounted for as much as one-third of the economy’s growth; when construction collapsed in the subsequent bust, it became the major cause of the 2008 recession.

Booms and Busts

Veteran home builders are much like wizened commercial fisherman—they have weathered many storms. Indeed, making it through the housing market’s ups and downs had been as tricky for builders as navigating an Atlantic nor’easter could be for a sailor. Over the years, rough economic weather had claimed as many builders as the ocean storms had ships at sea.

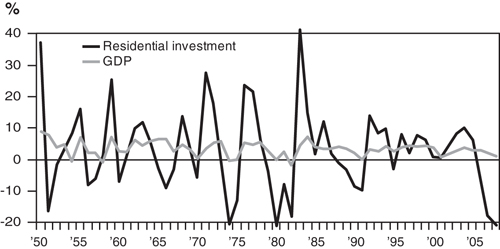

A housing storm could be extraordinarily severe. In nine housing busts since World War II, residential investment—the dollar value of all new housing construction and remodeling by existing homeowners—had dropped nearly 25% on average.1 Housing’s booms have been equally impressive, with average investment rising well over 50% during periods of growth. Home building’s swings dwarf those of the broader economy, which rarely deviates from its long-term growth trend by more than a few percentage points (see Figure 8.1).

Figure 8.1 Homebuilding is a very cyclical business.

Housing busts through the early 1980s were particularly harsh, exacerbated by credit crunch conditions—no loans available for anyone, no matter how good their finances. The problem: Only a banker could make a mortgage loan, and the banker could lend only as much as his depositors gave him. But depositors were fleeing traditional banks, which were barred by a Depression-era rule called Regulation Q from paying interest on checking accounts. As the Federal Reserve raised short-term interest rates to double-digit levels to quell the raging inflation of the 1970s, depositors moved their funds to money market accounts and Treasury bills, where rates were then far higher than in traditional bank accounts. As money flew out of the banks, mortgage credit for housing shut down.

Builders understood the dynamics of mortgage finance; they knew that when credit was ample, they had to take advantage of it, putting homes up to market as quickly as possible. Economic rebounds produced plenty of pent-up housing demand, from people who had put off home ownership during the lean times for lack of a loan.2 Builders worked hard to make money during a boom so that they could survive the inevitable bust.

Housing booms didn’t simply end after pent-up demand had been satisfied. Builders kept building as long as their bankers provided necessary up-front money to purchase cement and lumber, and hire masons and electricians. Even if builders wanted to plan around the market, it was hard to gauge the strength of housing demand or know how fast their competitors were adding to supply. Typically, builders misjudged and overdid it, constructing more homes than there were potential buyers. This set the stage for the next downturn.

The home building industry was largely a collection of small, privately held firms, each one focused on just a few neighborhoods. It was difficult for a home builder to venture far because his source of funding was a local banker, and banks were legally barred from crossing state lines to make a loan. If a builder wanted to expand to another state, he needed to find another banker. Local housing markets also tended to be idiosyncratic; building styles and desired amenities varied substantially from place to place. Knowing how to build center-hall colonials in New England suburbs wasn’t much use for constructing Spanish-style homes in the desert Southwest. Most builders stayed close to home.

Publics Ascend

Housing’s storms have moderated over the decades, the recent downturn notwithstanding. Regulation Q was phased out during the 1980s, and mortgage securitization came into its own, funneling capital from global financial markets to local U.S. mortgage and housing markets.3 By the mid-1990s, mortgage loans were almost always available; it was a question of the interest rate, which was generally falling, and the loan terms, which were easing.

By the mid-1990s, the fragmented housing industry was ripe for consolidation. Many of the nation’s smaller builders had failed or been severely hobbled by the late-1980s real estate bust and savings and loan crisis. Throughout Arizona, California, and the Northeast, it seemed as if the entire real-estate industry was in some stage of bankruptcy or liquidation. A nationwide home-buying market was also being created by the strong migration flows of households from the Northeast and Midwest to the South and West, and from California to the rest of the western U.S. Demographically speaking, Florida had become more like New York and Seattle more like San Francisco. The stock market was beginning its 1990s’ bull run, and investors were eager to finance the roll-up of small builders into large, publicly traded businesses. Those builders who were already publicly held had stock that was rising in value and could be offered to smaller builders to entice them to sell out.

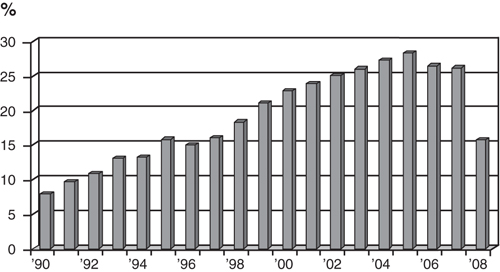

Home building acquisitions multiplied. A handful of major deals were made during the first half of the 1990s, but more than 50 were done during the decade’s second half. The merger wave spilled over into the first half of the 2000s, with such mega-mergers as Lennar’s purchase of U.S. Homes in 2000, Pulte’s 2001 purchase of Del Webb, and Beazer’s acquisition of Crossman in 2002. In 1990, public builders accounted for fewer than one in ten new home sales nationwide and generated no more than $10 billion in annual revenue. By 2000, their share of the market had surged to one new home sale in four, and at the peak of the boom in 2006, it had grown to nearly one in three, with sales of some $100 billion (see Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Public builders grab market share of new home sales.

As the publicly traded builders grew larger and their earnings seemed more predictable, their access to credit opened up, accelerating their expansion and tightening their grip on the industry. Construction and land-development loans—the money provided by bankers to finance home building—expanded three-fold during the first half of the 2000s to nearly half a trillion dollars. Major home builders could also tap the corporate bond market for cash; those borrowings soared from effectively nothing in the mid-1990s to well over $30 billion at the height of the housing boom.

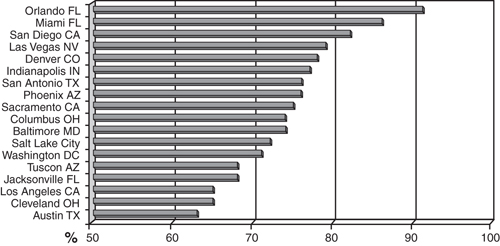

The big builders concentrated on the nation’s most lucrative and fastest-growing housing markets. Some two-thirds of their construction was in half a dozen states, including Arizona, California, Florida, Nevada, North Carolina, and Texas. The big firms completely dominate building in these markets; they account for nearly all home building in places such as Orlando, Florida; Fresno, California; and Las Vegas, Nevada; and more than three-quarters of house construction in San Diego, California; Miami, Florida; and Phoenix, Arizona (see Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.3 Where public builders build: share of home sales, 2007.

Not coincidentally, these are the areas where the housing boom turned into a bubble and where the subsequent bust was especially severe. Here the public builders were particularly aggressive about seeking to control developable land; this significantly pushed up prices for both land and houses because, in many areas, a home’s price is largely the cost of the land it occupies.4 Builders either bought vacant lots outright or took out options to buy them in the future. Options were preferred because little cash was needed to effectively gain control. In 2000, public builders owned or had options to buy 700,000 lots. By 2005, this had soared to 2.2 million lots, with nearly two-thirds optioned. Builders meant to construct as many homes as they could on this land, and that’s exactly what they did.

Optimism Overflows

As the housing boom gained momentum, builders felt they could do no wrong. Sales volumes and house prices were hitting new records, builders’ stocks tripled and then quadrupled in value, and there was plenty of cheap capital to finance more acquisitions and build out more communities. Builders were still like those fishermen, but now they were guiding large vessels equipped with satellite weather technology, and this made them certain they could avoid most storms and power through the rest. Some builders even seemed to believe that with their new financial tools and management acumen, they could make the housing storms go away permanently. It was certainly much easier to find a home buyer than a school of tuna.

Builders’ optimism resembled what technology entrepreneurs had felt during the Internet bubble a few years earlier. Many newly minted dotcom firms had never generated a profit, but as long as Internet traffic and advertising were booming, shareholders were convinced payday would come eventually. Dotcom stock prices had soared; the value of Internet-related tech companies went from close to nothing in the early 1990s to nearly $1 trillion before the bubble burst.

Tech executives had woven compelling stories. “E-tailers” would sell everything from pet supplies to industrial equipment; virtual stores would overwhelm bricks-and-mortar retailers; advertisers would abandon newspapers and television for the Internet; and professionals of all types would work from home over the Web instead of in nondescript office parks. All these predictions rang true—and, indeed, all have come to pass, to some extent—but not necessarily as scripted in the 1990s.

Investors eventually grew tired of hearing the stories; they wanted the Internet to start producing profits. As the decade ended, demand was turning soft; new customers were harder to come by, and existing customers had already purchased as much technology as they could digest. The tech companies didn’t give up without a fight, however. Some firms borrowed a trick from Detroit’s automakers: They started providing their customers with financing to buy their products. This worked for a while, but even easy money couldn’t keep increasingly stretched customers from cutting back forever. Some of those loans weren’t being repaid, moreover. The Internet bubble burst.

On the face of it, home builders seem to be the antithesis of the tech companies. There’s nothing virtual about a 3,000-square-foot home, and builders made plenty of money during the housing boom. Yet like the techs, the new publicly traded home builders became captivated by their own quickly rising stock prices. During the early 2000s, the stock market value of all publicly traded home builders surged four-fold to $150 billion. While not in the same league as the tech boom, this was financially intoxicating for the builders. They realized the only way to hold on to their newfound wealth was to demonstrate that their firms could consistently generate strong annual growth—if not at the pace of the 1990s dotcoms, then something close to it.

The builders developed some appealing stories to tell investors. Strong foreign immigration was a favorite. More than a million immigrants come to the U.S. every year—legal and illegal—and builders pointed out that all these people would need places to live.5 Given the period’s low mortgage rates and ample mortgage credit, new immigrants would likely gravitate toward single-family homes. Then there were the aging and affluent baby boomers, all of whom, builders asserted, were looking either to trade up to new, larger homes or to purchase vacation homes. Florida and South Carolina golf courses; condo towers in downtown Boston or Washington, DC; and mountain resorts in Idaho and Colorado were especially popular.

The builders weren’t wrong—these were indeed important sources of new housing demand—but they significantly overstated the case. The attacks of 9/11 crimped immigration more than they knew or let on, and many more boomers were worried about surviving in retirement than about finding the ninth tee.

As the home builders’ stories bumped up against the reality of a peaking housing market, the builders did what the techs had done: They became their customers’ bankers. Most builders had established mortgage-lending units earlier, but now they ramped up these activities to ensure a steady flow of credit to their increasingly pressed buyers. The largest builders, such as Pulte Homes and Centex, financed nearly all the homes they sold during the height of the housing boom. It was one-stop shopping for home buyers: a new home and the mortgage loan from the same place. The builders were glad to book profits from what was then a very lucrative lending business—but more important, they wanted to make sure sales weren’t deterred for lack of mortgage credit.

Awash in Homes

Builders had been aggressively constructing homes early in the 2000s, but in the 2003 summer building season, they really let loose. The initial angst over the Iraq invasion had passed, fallout from 9/11 and the 2001 recession was fading, mortgage rates had fallen to new lows, and subprime lending was coming into its own. The number of new homes added to the market—including completed single-family houses, condominium and apartment units, and pre-fab manufactured homes—jumped to well over two million a year.

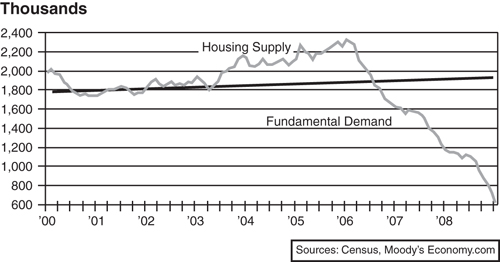

You can argue endlessly about what constitutes overbuilding, but two million units were clearly too many. At that pace, supply was growing substantially faster than demand. Fundamentally, housing demand equals the sum of all new households being formed, second or vacation homes, and homes being torn down for structural or economic reasons. This makes intuitive as well as mathematical sense: New households of whatever type—new college graduates, the newly married, or the newly divorced—must live somewhere. People who own second or vacation homes might not live there year-round, but they have no immediate plans to sell. A torn-down home or one blown away in a hurricane adds to housing demand as well; whoever lived there now needs a new home. Throughout the early 2000s, total fundamental housing demand consistently ran near 1.8 million units a year (see Figure 8.4).6 What had been a manageable gap between housing supply and demand early in the decade became an overwhelming gulf by the spring 2006 home-building season, when housing construction hit its all-time peak.7

Figure 8.4 Housing supply and demand: housing starts and manufactured housing.

Single-family home builders may have been initially fooled into thinking that the market could support a faster pace of building, because the effect of the early overbuilding had been felt mainly in rising vacancy rates for apartment rentals. The nationwide rental vacancy rate rose from 8% at the end of the 1990s to more than 10%, an all-time high, by the spring of 2004. The period’s low mortgage rates and easy credit were prompting tens of thousands of apartment dwellers to become homeowners.

Overbuilding in the single-family market was also disguised by the arrival of housing flippers, people who buy homes as an investment without intending to live in them. As the market heated up, these opportunistic buyers purchased several homes in a new community, intending to sell them quickly at a profit. It seemed like easy money; builders were eager to show prospective buyers that prices in their developments were rising, to spur prospective buyers to act quickly. Flippers, however, took this as vindication of their own investment strategy. Builders quickly grasped the risks this posed for them; as more flippers started showing up, builders began demanding that buyers declare their intention to actually live in the home they were purchasing. Some builders also attempted to restrict quick resales in their contracts with buyers. But these efforts were no match for crafty investors, who continued to gather up properties. Builders’ sales agents were also conflicted: Because their compensation was determined by sales volume, they had an incentive not to try too hard to weed out flippers. Better to make the deal, collect the commission, and move on.

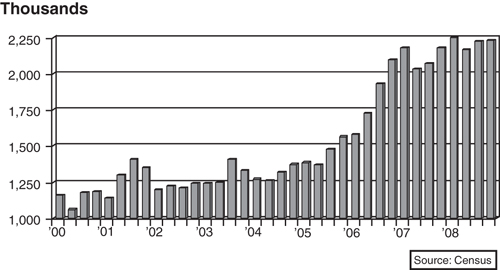

The enormous magnitude of overbuilding in the United States thus did not become clear until the housing bust. Only after flippers stopped buying—and were only selling—and only after foreclosures began to mount did the number of vacant homes for sale balloon. Even a well-functioning housing market has some unsold inventory, but a healthy level of inventory in today’s housing market would amount to no more than 1.25 million homes, roughly the level seen during the first half of the 2000s. By early 2008, inventories had surged to more than 2.25 million homes and were still climbing (see Figure 8.5). Compared with the total number of homes nationwide, inventories have never reached anything close to this level.8

Figure 8.5 Awash in homes: number of vacant homes for sale.

No one is more motivated to sell than a homeowner, banker, or builder trying to move an empty home. The property is generating no rental cash; meanwhile, there are property taxes and maintenance costs to pay, not to mention legal fees and a mortgage payment. Banks that take possession of homes dumped by flippers and hapless homeowners in foreclosure are exceptionally eager to sell. Homes sold in foreclosure generally go for about half their previous sale price. The financial pressure on home builders awash in unsold homes isn’t quite as intense, but they also tend to aggressively cut prices or offer large noncash incentives, such as built-in appliances, to try to move their vacant units. One large publicly traded builder, Hovnanian, drew special attention in late 2007 for its “fire sale” offer of six-figure discounts for homes in some high-end communities. Other builders offered up new cars or even college tuition payments to make their homes more attractive.

This was a housing nor’easter as severe as any that ever had roiled the home-building industry. The large public builders had not only failed to tame the economic weather, but they also had helped create a storm so large that it threatened to run nearly all of them aground.