20. Masters of the Universe

During the Great Depression, finance was unfashionable: “Don’t tell my mother I’m a banker, she thinks I play piano in a brothel.” Now, the best and brightest business school, mathematics, science, and computing graduates take jobs on Wall Street: “When it’s profit you’re after, why go after it the hard way? I intend to be a stockbroker...One attempts to make the most money with the least work.”1

In Lucy Prebble’s play Enron, the character Jeffrey Skilling, Harvard MBA, CEO of Enron and soon to be convicted felon, outlines the basis of the new economy: “the only difference between me and the people judging me is they weren’t smart enough to do what we did.”2 Money and brilliance became synonymous: “One of our culture’s deepest beliefs is expressed in the question, ‘If you are so smart, why ain’t you rich?’...people in finance are rich—so it logically follows that everything they chose to do must be smart.”3 John Kenneth Galbraith’s caution would prove well founded: “Nothing so gives the illusion of intelligence as personal association with large sums of money. It is also alas an illusion.”4

Money Illusions

Between 1980 and 2005 in the United States, jobs trading financial assets increased from 2.8 to 9 percent of all finance jobs. During the same period, jobs entailing risk modeling increased from 1.2 to 5 percent. The value contributed by finance to the economy increased from 2.3 percent after the Second World War to 4.4 percent in 1997 and 8.1 percent by 2006. In 1980, finance professionals earned the same as engineers. By 2005, financial engineers, on average, earned around 30–40 percent more than real engineers.5 In the UK the financial sector made up 10 percent of the economy, contributing 27 percent of tax revenue.

Banking embodies a clear class structure. The vast majority of bankers remained ordinary men and women involved in mundane activities, helping their customers and keeping the wheels of the financial system turning. But now a new super class of bankers and elite financiers emerged, reflecting the changes in banking and the financial system.

In 1989, Michael Lewis, in Liar’s Poker, set out his experiences at Salomon Brothers, as a highly paid 24-year-old with minimal training providing investment advice and making large bets with other people’s money. Intended to highlight the absurdity, the book instead became the manual for how to succeed in banking.

In the 1970s, Pierre Bourdieu, a French anthropologist, introduced the idea of habitus—how each society and culture orders its world subconsciously according to a cognitive framework based on its experiences. He argued that: “The most successful ideological effects are those which have no need of words, but ask no more than a complicitous silence.”6 Class, affinities, education, and the work itself shaped the financial elite.

In the sixteenth century the Conquistadors brought the ambitions, prejudices, attitudes, and values of Spain to the New World. Achievements were validated with riches, rank, and power. Failures brought disease and death, mollified by the consolations of faith and the afterlife. The financial elite undertook similar conquest and plunder, marshaling vast sums of money and creating intricate financial structures. In the new age, Masters of the Universe strutted through the City of London, Wall Street, Finanzplatz Deutschland, Zurich’s Bahnofstrasse, Singapore’s Raffles Place, Hong Kong’s Exchange Square, and Tokyo’s Marunouchi, parodying a banker in the movie The Bank who believes he is just like God, but with a better suit.

Factories for Unhappy People7

In the 1967 film The Graduate, Dustin Hoffman’s character Ben Braddock received career advice. Then it was “PLASTICS,” now it was “MONEY.” Finance now was the “hot” professional ticket, attracting between 20 and 40 percent of graduates from the best universities.

MBAs (mediocre but arrogant or mostly bloody awful) became conveyor belts for the finance mill. In cocooned campuses resembling Baghdad’s Green Zone,8 students focused on courses like Biggie (business, government, and international economics). Laboring long hours, one student thought he was gaining a “Swiss army knife...toolkit of skills’ and becoming a real ninja at using [them].” He sought solace in the aura: “the great thing about studying economics at the University of Chicago is that most of what you learn...was invented, or...affected significantly, by research done within one square mile of where you are.”9 Business Schools boasted that you were never more than two degrees of separation from powerful figures—the president of a nation, the head of a central bank or CEO of an investment bank.

MBAs gave graduates a narcisstic self-confidence—the belief that they were 100 percent right, 100 percent of the time. Asked about the benefits of a MBA in 1986, Russell Ackoff, a professor at the Wharton Business School, replied:

The first was to equip students with a vocabulary that enabled them to talk with authority about subjects they did not understand. The second was to give students principles that would demonstrate their ability to withstand any amount of disconfirming evidence. The third was to give students a ticket of admission to a job where they could learn something about management.10

An MBA was nothing more than a union card for the financial elite.

War Versus Money

Scientists traded in real union cards to trade on Wall Street as available academic and defence jobs decreased. They flocked to make money not war.

Each year 150,000 people in the United States alone sit examinations to earn the letters CFA—certified financial analyst. The CFA and financial engineering program such as CQF (certificate in quantitative finance) were an entrance ticket to lucrative careers on Wall Street. Sylvain Raines, an experienced quant, joked that quantitative finance was an oxymoron as “finance is quantitative by definition...this is like saying aerial flight or wet swimming.”11

Newly graduated financial experts applied simple “phenomenological toys” to markets. Most financial models are wrong, only the degree of error is in question. Differential equations, positive definite matrices or the desirable statistical properties of an estimator rarely determine the price of traded financial instruments.

Goldman Sachs’ Emanuel Derman, a trained physicist, identified the difference: “In physics, a model is correct if it predicts the future trajectories of planets or the existence and properties of new planets.... In finance, you cannot easily prove a model right by such observations.” Derman ruefully concluded: “Trained economists have never seen a really first-class model.”12 Commenting on the required level of quantitative knowledge of people involved in financial markets, Derman once observed that Tour de France bicyclists did not need to know the laws of physics. But it helped to know that at certain speeds and angles you come off the bike.

Quants and bankers barely understood each other: “The members of each discipline are proud of the fact they know nothing about other disciplines.”13 MBAs believed the models. Quants worshipped the models they built. But turning models into money-making machines required the skills of the traders: “Reeling and Writhing, of course, to begin with, and the different branches of Arithmetic—Ambition, Distraction, Uglification, and Derision.”14

Traders understood that prices are based on ever-changing, frequently irrational opinions. They understood that the players “don’t know when they’ve lost, so they keep trying.”15 In Wall Street, Gordon Gecko (Mike Douglas) derisively dismisses Harvard MBA types as not adding up to dog shit. He wants guys who are poor, smart, hungry, without feelings and who keep on fighting.

During the global financial crisis, the Financial Times published a spoof ad for the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) targeting financiers: “You didn’t see the financial crisis coming. We missed 9/11 and the end of the cold war. Sounds like a match made in heaven—particularly now that you’re unemployed.”16

Shop Floors

The ritual theater of campus recruitment, the hunting season, is dominated by words like “smart,” “intelligent,” and “challenging.” It is the idealized vision of bankers: ‘They are the elite of Wall Street. Their offices are as furnished with expensive antiques and original works of art. They...are as quick to place a telephone call to Rome or Zurich or Frankfurt as most Americans are to call their next door neighbor.... His art is arcane.”17

New recruits rapidly discover a different reality. Banks don’t even trust the skills of recruits, putting them through extensive training programs: “You are perfect, now could you please change?” Then, there’s the work.

Investment banking is coverage or product. Coverage is constant client meetings and spending 24/7 preparing thick, glossy, spurious pitch books, glanced at cursorily and thrown into waste bins. Reams of analysis are only to persuade clients to do something, anything, which results in fees for the bank.

Product means mergers and acquisitions or fund raising. Mergers involve endless research, positing what a company should do. Dense, stupefying valuations are prepared, showing how every proposed transaction will boost share prices. Fund raising is proposals to raise more money, more cheaply, via the latest opportunities and market windows.

Trading is selling or speculation. Selling is endless cold calling, puffery or inane chatter, masquerading as market color (commentary) or trading ideas. No one can provide what everybody is really interested in—the sure, sure thing. Traders chafe under the relentless pressure of making money or not losing money.

In risk management, you learn that you are irrelevant, despite everybody saying you are vital. In the back office, you are chained to the oars of the banking trireme, processing an avalanche of paper. If you are not a producer then you are a cost center, expected to perform magic tricks daily to keep the machine going.

Misinformed

Banks take smart people and plug “them into [their] dull, trivial culture” where they “waste their lives on the hamster wheel of corporate life.”18 There is a mismatch between expectations and the reality of banking, echoing a scene in the film Casablanca. Asked by Captain Renault what brought him to Casablanca, Rick (played by Humphrey Bogart) replies that he came because of his health, to take the waters. A surprised Captain Renault informs Rick that they are in the desert. Rick ironically rejoinders that he was misinformed.

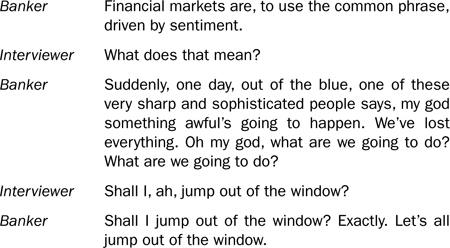

The assumed sophistication of finance and financiers is greatly overrated:19

Gaining an edge is crucial, sometimes involving unusual initiatives. A trader at Steve Cohen’s SAC Capital was allegedly forced by his boss to take female hormones and wear articles of women’s clothing at work, leading to a sexual relationship between the men, one of whom was married. The bizarre behavior was to eliminate the trader’s aggressive male attitude, making him a more obedient and detail-oriented trader.20

Amar Bhide, a professor of business at Harvard, coined the phrase hustle as strategy. Banks have no strategy, only hustle. One bank decided its strategy was to have no strategy. Instead it hired smart people and backed them. Imitation is the only real strategy.

The culture does not create leaders, instead producing tyrants and dictators. Richard Fuld, CEO of Lehman Brothers for almost two decades, was “neither a leader nor a dazzling intellect.”21 In the culture of the deal, banks endlessly copy each other’s strategies or products, chasing the same customers, competing on price and the ability to take risk. Complex systems of fealty exist within firms. Fiercely secretive, bankers are reluctant to share information, seeking an edge over their internal and external competitors. People eat what they kill.

Despite affirmative action programs and considerable lip service to modern employment practices, the firms are backward in their treatment of women, minorities, and cultural differences. A proudly misogynist culture dominates at every level. Joseph Akermann, head of Germany’s Deutsche Bank, thought that adding women to the firm’s men-only management board would make the forum “more colorful and prettier.”22 In 2007 Morgan Stanley agreed to pay $62 million to settle a number of gender discrimination claims bought by female employees.

Writing about her experiences at the 2011 World Economic Forum in Davos, journalist Anya Schiffrin, the wife of economist Joseph Stiglitz, recorded the humiliation of the women who make up a small portion of attendees. In a world where titles on conference badges are everything, the plain white name badges defined a wife’s low status. The only position that is worse is that of a Davos mistress, who usually does not get a badge at all.23

Smiling and Killing

French philosopher Michel Foucault identified a carceral continuum, the system of cruelty, power, supervision, surveillance, and enforcement of acceptable behavior affecting working and domestic lives. Banking has its equivalent. It is the world of the film Crimson Tide, where Captain Ramsay tells sailors that rules are not open to personal interpretation, intuition, gut feeling, the behavior of the hairs on the back of the neck, or the whispers of little devils and angels sitting on your shoulder. Recruits must adapt to the unforgiving culture or die.

Sociologist Zygmunt Bauman’s metaphor of liquid and solid modernity captures the shift from a society of producers to a society of consumers. Security gives way to increased freedom to purchase, to consume and to enjoy life. In liquid modernity, individuals have to be flexible and adaptable, pursuing available opportunities, calculating likely gains and losses from actions under endemic uncertainty. It was a metaphor for the rise of financiers and the financialization of everyday life in a volatile world where risk taking and speculation was an essential survival strategy.

In Liquidated, anthropologist Karen Ho documented the culture of modern banking.24 Instead of the expected royal treatment, the best and brightest must work like indentured slaves for up to 140 hours a week. Lacking job security and facing constant performance pressure, bankers survive by trading things or cutting deals. Ho’s title evokes Bauman’s idea of liquid modernity. Bankers made assets liquid or tradable. As highly liquid assets themselves that could be easily liquidated, they lived in constant fear. They learned the truth of an old Wall Street saying: “Never tell anyone on Wall Street your problems. Some don’t care. Most are glad you have them.”

The environment creates a culture where narrow, short-term self-interest dominates. It drives creation and sales of products of no intrinsic value. Fear of liquidation eliminates misgivings about profitable transactions that might result in enormous pain for others.

Bernard Madoff perfected affinity fraud, preying upon unwitting members of his religious and ethnic communities, enlisting leading figures to promote fraudulent investments through the country clubs of Long Island and Palm Beach. Former Salomon Brothers economist and Lehman Brothers board member Henry Kaufman, along with stars such as Steven Spielberg, Jeffrey Katzenberg, Kevin Bacon, John Malkovich, Zsa Zsa Gabor, and Larry King lost money. The Elie Wiesel Foundation for Humanity, founded by holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel, lost $15.2 million. Investors should have heeded Groucho Marx’s observation about not belonging to any club that would have him as a member.

In Bret Easton Ellis’ novel American Psycho, Patrick Bateman is a successful, intelligent, and charming Wall Street banker who outside working hours is a vicious psychopathic killer. But elite bankers don’t only behave this way at night. At the start of the book, Bateman stares at blood-red graffiti that alludes to Dante’s hell: “Abandon all hope ye who enter here.” At the end of the book, Bateman sits in a bar staring at a sign: “This is not an exit.”25 Any Faustian bargain comes with a price.

Pay Grades

The pay was the only thing that made it all tolerable. As Jeffrey Skilling, the former president of Enron, knew: “all that matters is money.... You buy loyalty with money...touchy feely stuff isn’t as important as cash.”26 The character Jeffrey Skilling in the drama Enron says: “Money and sex motivate people...money...gets their hand off their d**k and into work.”27

In 2006, investment banking accounted for just 0.1 percent of all U.S. private sector jobs (173,340 out of 132.5 million jobs), yet accounted for 1.3 percent of all wages. The average weekly wage of investment bankers was $8,367, compared to $841 for all private sector jobs. In Fairfield County, Connecticut, where many hedge funds were based, the average pay was $23,846 a week.28 In 2007, the combined remuneration at the five major Wall Street investment banks alone exceeded the world’s total foreign aid budget of $850 billion.

The leading 20 hedge fund and private equity managers earned $657.5 million in 2007—$12.6 million a week or $210,737 an hour (assuming a 60-hour week). They earned the $29,500 average annual income in the U.S. in just over 8 minutes. They earned the President’s salary (around $400,000 per year) in less than 2 hours.29

At a conference on the Australian economy, CEO of Macquarie Bank Allan Moss, who annually earned A$33.5 million, was shocked to discover that the best paid teachers earned A$65,000 per year (less than 0.2 percent of his remuneration). Moss was not entirely out of touch with domestic economics, being spotted presenting a voucher entitling him to a 4-cent-per-litre discount on fuel purchases.30

Bankers get paid a base salary, $35,000 to $500,000, but performance based bonuses can total up to 100 times that. The structure makes compensation costs variable, matching the volatile nature of investment banking.

Although senior bankers everywhere were well paid, the über bonus is a recent phenomenon. Until the mid 1990s, multimillion dollar bonuses were unusual. Traditionally, investment banks were partnerships where gentlemen worked together, sharing profits. For employees, the golden ring of partnership was the prize. At “Goldmine” or “Golden Sachs,” becoming a partner was winning the lottery, every year. As investment banks became publicly owned or part of commercial banks, the promise of the partnership was lost and bonuses became important in compensating and retaining staff.

Large bonuses and increasing profits went hand in hand. Traditional partnerships had limited capital, confining themselves to primarily arranging deals. Access to more capital from shareholders (where publicly held) or commercial banks (who owned them) allowed investment banks to trade on their own account and take greater risks.

Much More Than This

Learning about former CEO of Goldman Sachs and U.S. Treasury secretary Hank Paulson’s bucolic lifestyle, playwright David Hare mused: “Why does anyone need $500 million, or whatever he got from Goldman, to live in Idaho?”31 Bankers argued that it was reward for talent and expertise. Society benefited from the banker’s work: “Tell the masses...you are inferior and all the improvements in your conditions which you simply take for granted you owe to the effort of men who are better than you.”32

Larry Summers believed that the market allowed skilled talent to capture their fair share of returns, consistent with productivity and contribution to economic outcomes. Between government jobs, Summers earned $5 million at hedge fund D.E. Shaw & Co., playing down his role as a mere part-time job.

Bankers blamed the high cost of living in major financial centers like London and New York. There was the need to maintain an expected life style—private schools, private trainers, private chefs, etc. It was pure Woody Allen: “Money is better than poverty, if only for financial reasons.”

Large bonuses were based on high profits, the product of excessive risk and leverage. Some of the earnings were imaginary, based on mark-to-market accounting not true cash profit. Bankers mastered the art of “seeing where the arrow of performance lands and then painting the bull’s eye around it.”33 Banks paid out non-existent earnings to employees because everybody was doing it.

In 2008, Stan O’Neal, CEO of Merrill Lynch, said that: “As a result of the extraordinary growth at Merrill during my tenure as CEO the board saw fit to increase my compensation each year.” In 2006, when Merrill had record earnings of $7.5 billion, the firm handed out over $5 billion in bonuses. Dow Kim, head of the Merrill’s fixed income business including mortgages, received a bonus of $35 million on top of his salary of $350,000. A 20-something year old analyst collected a bonus of $250,000 on top of a base salary of $130,000. A 30-something year old trader collected a bonus of $5 million on top of a base salary of $180,000. Merrill ultimately lost vast sums when the basis of the profits, mortgage investments, fell sharply in value.34

Joining CitiGroup after his term as Treasury secretary, Robert Rubin was paid $20 million a year, as a non-executive board member with poorly defined duties. During the tenure of Rubin and CEO Chuck Prince, Citi lost over $50 billion and its market value fell by more than $60 billion, ultimately requiring a government bailout.

Even failure was well rewarded. Upon leaving, Merrill’s Stan O’Neal received $30 million in retirement benefits as well as $129 million in stock and option holdings, in addition to the $160 million he earned during nearly five years as CEO. Chuck Prince was paid an exit bonus of $12.5 million, additional to $68 million already received in stock and options, a $1.7 million annual pension, as well an office, car, and driver for up to 5 years. Prince signed a 5-year noncompete agreement. Citi may have benefited more by allowing their former CEO to manage a competitor, given the results of his tenure at the bank.

Tight circles of directors, senior managers, and consultants determine salaries. Benchmarking exercises merely reinforce the norm, with packages justified as “needing to buy the best talent” or “meeting the demands of a competitive market.” John Kenneth Galbraith identified this pattern: “The salary of the chief executive of the large corporation is not a market award for achievement. It is frequently in the nature of a warm personal gesture by the individual to himself.”35

The conventional view was that the global financial crisis wiped out the wealth of senior executives, because they were significant shareholders of their banks. While executives suffered losses, top executives of Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers had cashed out. The top five executives at Bear Stearns and Lehman pocketed cash bonuses exceeding $300 million and $150 million respectively (in 2009 U.S. dollars). Although the earnings on which the remuneration was based were reversed in 2008, the executives did not return the payments received.36

Salli Krawcheck, a former CFO at Citi, observed: “it’s better to be an investment bank employee than shareholder.”37 Andy Kessler, a former Wall Street research analyst, noted: “Wall Street is just a compensation scheme.... They literally exist to pay out half their revenue as compensation. And that’s what gets them into trouble every so often—it’s just a game of generating revenue, because the players know they will get half of it back.”38

There were crumbs from the bankers’ feast for all. Regulators were seduced with invitations to all-expense-paid lavish conferences and speaking engagements. Modest current salaries were compensated for by post-retirement sinecures in banks. In Japan, each summer senior government officials retired and underwent amakudari (descent from heaven), taking up lucrative jobs in private firms in the industries they had previously regulated.

Charles Ferguson’s film Inside Job exposed prestigious academics and former regulators who were paid large consulting fees by financial institutions and even countries to espouse a particular point of view. Former Federal Reserve vice-chairman Frederic Mishkin, the film revealed, was paid $124,0000 for touting Iceland as a well-run banking center shortly before it imploded. A study originally titled “Financial stability in Iceland” was included mysteriously in Mishkin’s CV as “Financial instability in Iceland.” Confronted on camera about conflicts of interest, the film captured Harvard’s Martin Feldstein glowering, squirming, and smiling, in the words of one reviewer “like Yoda with a hemorrhoid.”39

Warren Buffet recognized that the system produced “wildly capricious” results. “I’ve worked in an economy that rewards someone who saves the lives of others on a battlefield with a medal, rewards a great teacher with thank-you notes from parents, but rewards those who can detect the mispricing of securities with sums reaching into the billions.”40

Attached

Attachment theory in psychology focuses on a child’s need to develop a relationship with someone for normal social and emotional development. The banking elite attached themselves to money: “in the real world...[if] people aren’t making that much money, then they don’t really matter. They don’t count, so you can treat the guy who gives you coffee as a lesser citizen.”41 Converted into commodities, in fear of being liquidated, bankers sought the safety of liquidity: “As long as I get the bonus that I want, I’ll stay. Otherwise...I will just leave...everyone is looking out for himself.”42

Originally the primary means of acquiring wealth was robbery, privateering, and force rather than capital accumulation. Bankers reverted to these traditional activities to generate rewards, vacuuming up every last entitlement. They worked just past the hour entitling them to free meals and a car-service ride home. Travel expenses were routinely misstated. Goldman Sachs offered a generous health benefits package, including coverage of sex reassignment surgery.43

If you liked to go hunting or shooting then you just invited your clients along for the day. In Japan, salary men bankers routinely entertained Western clients on the bank’s account. They lost the client quickly to get on with the night’s revelry unhindered. Everywhere, sporting events, and expensive restaurants co-existed with adult entertainment. Some bankers regularly paid prostitutes to entertain clients. One broker described a fishing trip as an extended orgy, a customer drinking, and drug party.

For the jaded palate, there was London’s ginger pig butcher. Clad in white coats, bankers, investors, hedge fund managers, and lawyers paid more than £120 each to learn how to carve up carcasses. As banks routinely butcher and carve up clients, the parallel was appropriate.

The system of entitlement was visceral. Gaining entry to MBA courses, students deliberately ran down bank accounts to qualify for larger student support by buying expensive new cars—“financial aid” BMWs. As cars were not listed as assets, the students qualified for more financial assistance. When Lehman Brothers filed for bankruptcy, bankers filed out grasping plaintively at small cardboard boxes, full of sandwiches, drinks, chocolate bars, and other food items. As the firm’s canteen worked on a still-functioning internal staff credit system, the bankers were in fact looting its contents.

Bonus Season

Each year, from around September, the bonus season is in full swing. Donors huddle in meetings, while supplicants lobby, submitting puff sheets of exaggerated contributions to earnings. Timely opinion pieces in trade magazines, speeches at conferences or increased press profile lend support to their case for larger bonuses. Some solicit form letters of commendation from clients extolling their talents. Some resort to veiled threats of opportunities elsewhere.

Managers use the number to manage their charges, while keeping the lion’s share of the plunder themselves. If a manager has ten people in their department, then reducing each person’s bonus by $100,000 increases the manager’s own share by $1 million. Happy employees mean that you have paid them too much. Disgusted employees mean that you have paid them so little that they will leave. The optimal point is between satisfied and dissatisfied—enough to keep you but not enough to make you complacent or diminish the manager’s own bonus.44

On the day of announcement, the earlier you are called in the better. The later you attend, the more difficult the conversation is likely to be. “The firm and markets are facing challenging times.” “You are being promoted to head of EMEA Trading in Local Currency.” “We have stretched to pay you one of the highest bonuses within your comparable group.” “There is a mismatch between your talents and the job.” All these mean that your bonus is low. The really out-of-favor have already been removed from the bonus pool by transfers to other departments late in the year or outright dismissal. The better conversations home in quickly on the money, there being so little else to say.

In 2009, one junior trader protested that he could not possibly maintain his lifestyle or his investments on the number. The recipients of larger bonuses register a muted protest, to establish the ground for a higher number next year and demonstrate the hunger that firms value. The real angst comes when you discover that you got $1 million but someone else got a dollar more.

Plenty

Successful bankers, like Lehman’s Richard Fuld and Bear Stearns’ James Cayne, took nearly 2 decades to become multimillionaires and finally billionaires. A less patient, new generation aspired to become hedge fund and private equity managers where the 2/20 percent formula gave them a share of the action. Brian Hunter, responsible for energy trading at hedge fund Amaranth before it imploded, earned between $75 million and $100 million in 2005, ranking him a middling 29th highest paid in his profession. Several hedge fund managers routinely earn $1 billion each year.

When hedge fund Fortress went public in 2007, at the end of the first day of trading Wes Edens, one of the founders, was worth $2.3 billion on paper and Fortress’s total market value was $12.5 billion. By 2007, nearly half of the 40 richest people in the United States had made their fortunes in private equity or hedge funds—David Bonderman and James Coulter of TPG, William Conway, Daniel D’Aniello, and David Rubenstein of The Carlyle Group, Peter Peterson and Stephen Schwarzman of The Blackstone Group, Daniel Och of Och-Ziff Capital Management, and Steven Cohen of SAC Capital. The youngest was 33-year-old John Arnold, a former Enron trader, who set up hedge fund Centaurus Energy and was worth an estimated $1.5 billion.

Chuck Prince’s successor as CEO of Citi, Vikram Pandit, started the hedge fund Old Lane Partners after leaving Morgan Stanley. After Citi purchased the fund for $800 million, Pandit joined Citi as head of its Investment Management Unit—the “$800 million man.” After poor performance, Citi shut down the fund and wrote down its investment.

The monetary measure of true success was “never having to fly commercial.” In Wall Street, Gordon Gecko thought that having your own jet was what qualified a true player in the game—someone who was rich enough not to have to waste time. Everything else amounted to nothing.

Tipping Points

Bankers were getting a disproportionate share of the profits with no liability for losses, under a bonus system that encouraged excessive risk taking. Firms tinkered with the bonus system. In 1994 Warren Buffett tried to stop bonus payments until Salomon Brothers’ profitability returned to satisfactory levels. Buffett was forced to abandon the proposal when many senior staff left, joining competitors. A financial firm’s assets well and truly go down in the elevator at the end of every day.

The mobility of and competition for staff made it difficult to change the system. Payouts were deferred over a number of years and a portion was in deferred stock or stock options. Competitors poached successful bankers or traders, matching deferred compensation in new stock or cash, adding large signing on bonuses and multi-year guarantees.

During negotiations with the U.S. government to invest $10 billion of tax payers’ money directly in Merrill Lynch to avoid risk of failure, John Thain, Stan O’Neal’s successor, was concerned about how this would affect executive compensation.45 Even the U.S. Bankruptcy Court approved a bonus pool of $50 million for the remaining derivative traders at bankrupt Lehman Brothers, who had been kept on to wind down its transactions.

Dissatisfied with his number, a young banker protested that it “was not a bonus! It’s a tip!” A tip or gratuity is a noncontractual payment for special service, sometimes related to the relative status of the parties. No doctor or surgeon expects to or receives a tip for doing their job properly.

The bonus culture encouraged moral hazard—a focus on narrowly quantifiable outcomes while ignoring wider risks and costs. Elite bankers and traders took risks with other people’s money, aware that if they won the bet they would get a significant share of profits, while suffering no permanent damage if they lost.

In a comedy sketch featuring British comedians John Bird and John Fortune, the interviewer asks: “Can we talk about moral hazard?” The banker responds: “About what?” The interviewer reiterates the question: “Moral hazard?” The banker says: “I know what ‘hazard’ means, but what’s the other word?”46 As Adam Smith bemoaned: “All for ourselves, and nothing for anyone else seems, in every age, to have been the vile maxim of the masters of mankind.”47