Chapter 6. Emerging Markets

“The other boys at Yale came from wealthy families, and none of them were investing outside the United States, and I thought, ‘That is very egotistical. Why be so shortsighted or nearsighted as to focus only on America? Shouldn’t you be more open-minded?’”

Emerging markets pioneer Sir John Templeton

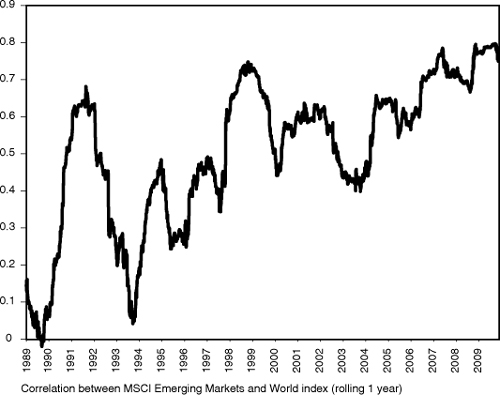

The launch of investment funds to buy shares in emerging stock markets created a new asset class and allowed investors easily to pull money in and out of the developing world for the first time. Before this, emerging markets were totally uncorrelated with developed markets; by 2009, they moved in lockstep.

Until 1982, financing for the world’s Lesser Developed Countries (LDCs) was driven by commodity prices and western banks. As rising oil prices created greater wealth and western banks looked for new sources of business, banks came to make variable-rate loans directly to emerging countries’ governments—not their companies. José López Portillo, then president of Mexico, told his people they should “learn how to administer abundance” as he expanded oil production, while the banks financing this took refuge in the belief that countries do not go bust.

But in 1982 the LDCs model collapsed, after Mexico was forced to devalue its currency and then renegotiate its debt with lenders—a pattern that then repeated across Latin America. Within a year, there came a radical new way to invest outside the developed world. In place of lending to the LDCs, there arose the Emerging Markets, as the fund management industry started to offer pooled investments in exotic stock exchanges. This had huge consequences for what had been known as the Third World. It also changed investors’ behavior and contributed to the synchronized expansion and contraction of markets around the world. In the 1980s, emerging markets and the developed world had nothing to do with each other and were totally uncorrelated; by 2009, the correlation between them was almost perfect.

What drove this shift? Mexico, then the biggest and most advanced of the emerging markets, suffered from misguided ambitions, which bankers in the United States were only too happy to finance. They desperately needed new source of business to replace the revenues they were losing to the commercial paper market at home. While Paul Volcker was making money expensive in the United States, it was much easier to look for bargains elsewhere.

The banks also had a lot of money to invest. The oil price spike had left the big oil-producing nations of OPEC with surplus funds, generally labeled petro-dollars, which they deposited in the banks of the United States and Western Europe. Faced with swollen coffers, banks behaved irresponsibly—a phenomenon that recurred during the next great oil spike in 2007 and 2008.

LDCs gave the petro-dollars a natural home. The Third World had been growing steadily since the 1960s, and its need for financing ratcheted up after the 1973 oil spike pushed up their costs. López Portillo was not the only Latin American leader eager to accept the banks’ terms. And so money poured from U.S. banks into Latin America, and particularly Mexico. At the end of 1970, Latin America owed a total of $29 billion. By the end of 1978, on the eve of the second oil spike, it owed $159 billion. By the 1982 crisis, the region’s indebtedness doubled again, to $327 billion.1 Banks clubbed together to make the loans, which had a variable interest rate, and were denominated in dollars, meaning repayments could rise sharply if a country’s currency devalued. Rather than investing in companies, the game was to lend to national governments on the basis that, in the words of Walter Wriston, who led Citicorp at the time, “The country does not go bankrupt. Any country, no matter how badly off, will ‘own’ more than it ‘owes.’”2

But in some circumstances, countries do go bust. The circumstances that led Mexico and the U.S. banks into each other’s arms in the first place also bore the seeds of eventual disaster. The money ignited an unsustainable boom in Mexico, where inflation took hold. Meanwhile higher rates and lower inflation in the United States under Volcker pushed up the value of the dollar, and with it the cost for Mexicans of servicing their debt. López Portillo vowed to defend the peso “like a dog,” but in the summer of 1982, just as the U.S. stock market started to rise, he had no choice but to devalue. That meant disaster for Mexico and its creditors, which deepened when the president nationalized all of Mexico’s banks.3

Where Mexico led, others followed. By October 1983, 27 countries were rescheduling their debt, and the Latin American region entered what is now known as the “lost decade.” Meanwhile, a Mexican currency crisis soon spurred a U.S. banking crisis. Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela, and Argentina owed $37 billion between them to the eight largest banks in the United States. This was almost 50 percent more than those banks held in capital and reserves at the time. These crises took nearly a decade to resolve as countries renegotiated loans, while U.S. regulators allowed banks to limp along on life support rather than forcing them to recognize all their losses. This lenient treatment arguably encouraged greater risk-taking for the future.

The LDCs crisis set a pattern that has now been repeated several times. U.S. banks showed a knack for making massive loans that they knew might not be repaid. Problems for the poor, in this case Latin Americans, soon translated themselves into problems for the wealthy (big U.S. banks). High commodity prices blurred judgments and drove excessive flows of money into small markets, thus destabilizing them. And the motors that drove the crisis, far from Mexico, were the international price of oil and the state of the credit market in the United States. All these conditions recurred in the crisis of 2008.

But in 1982, the World Bank had a more immediate problem: How could the world’s poorer nations finance their rapid growth? Lending to them was dangerous, and the countries themselves badly needed to reduce their reliance on debt. Antoine van Agtmael, a young Belgian official at the World Bank, thought that investing directly in growing companies would be more appealing. If things went well, there was far more “upside,” or potential profit to be made. And if things did not go well, it would be far easier for companies to skip a dividend payment than to default on a loan.

The job of vetting and valuing companies in countries like Brazil or South Korea, however, was prohibitively expensive for most investors. Often such companies did not even have recognizable balance sheets or accounting standards. Political, cultural, and language barriers were immense. If companies failed to uphold commitments, local courts could not be relied on for support. The World Bank only took direct stakes in companies, rather than buying shares on the stock market. So even if there were opportunities for growth in the Third World, it was not worthwhile for big fund managers in the West to search them out.

Another problem van Agtmael needed to address was simple image or “branding.” After 1982, nobody wanted to invest in LDCs. The answer, reasoned van Agtmael, was to set up a fund. He and his colleagues would do the hard work and investors would have a shot at big gains. Portfolio diversification, or “safety in numbers,” would help. Invest in many countries, and the risks posed by political or legal upheaval in any one of them diminished. He proposed to call this the Third World Equity Fund.

Van Agtmael’s colleagues told him this was a terrible name. Then, “a light bulb went off in my brain,” says van Agtmael. “Who wants to invest in the Third World? They weren’t even second-rate; they were third-rate. That’s when I came up with ‘emerging markets,’ which I felt had a little more pizzazz.”4 The name suggested “progress, uplift, and dynamism”5 rather than the stagnation that went with the “Third World.” In short, he wanted to rebrand a large swathe of the world and to create a new class of assets for investors to invest in. And he succeeded.

The transition from LDCs to emerging markets proved to be momentous. While the former tended to be in Latin America, now mired in its “lost decade,” the latter would be associated more with the booming “tiger” economies of South East Asia. South Korea, arguably the greatest success story of the twentieth century, was completing its transition from a war-torn peasant nation into a modern, highly developed exporting powerhouse. It was even hosting the Olympics. Taiwan was close in its wake, followed by Thailand and Malaysia.

Van Agtmael and the World Bank did not have the field to themselves for long. As the model worked, others soon entered the market. Their job became easier, and the definition of “emerging market” became clearer after Morgan Stanley Capital International (now MSCI Barra) started its emerging markets index at the beginning of 1988. This made managers feel safer by giving them an index to group around. Like other indices, the MSCI soon outgrew its status as a passive benchmark to become an active guide to their investing.

Investing in that index proved to be mighty profitable. The MSCI index started on New Year’s Day 1988 at 100. By November 1994, it stood at 563—staggering growth that attracted money from all sides. Initially, its correlation with the MSCI World index, covering the world’s developed markets, was minimal. It even briefly went negative in 1989, suggesting that emerging markets provided a true hedge against events elsewhere in the world.6

But as more and more investors bought into emerging markets, their money began to drive them. If investors were feeling optimistic, then emerging markets allowed them to take more risk with the chance of bigger returns. If they were pessimistic, risky emerging markets stocks would be the first they sold. Over time, MSCI’s emerging markets index correlated ever more closely with the developed world. By 2009, as Figure 6.1 shows, most of its daily movements could be explained by changes in the World index. Investors could easily expose themselves to the volatility of emerging markets. But it was perhaps more concerning that those emerging markets were now exposed to the volatile behavior of western investors.

Figure 6.1. Emerging markets: ever more in sync

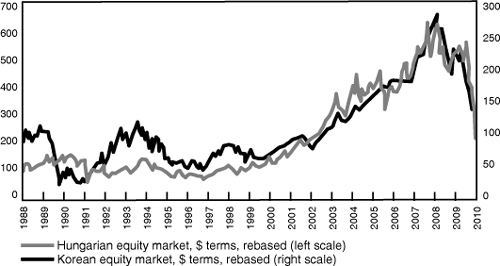

The benchmark helped ensure that very disparate markets rose together. South Korea and Hungary, for example, have few things in common (and neither has much in common with Estonia), but gradually they and all other emerging countries started to move in unison (see Figure 6.2). Booming regions would help attract funds to regions that were in difficulties.

Figure 6.2. Hungary and Korea—separated at birth?

But the growth of the emerging markets was a classic example of how financial engineering led to lasting changes in the real economy. Similar financial engineering in the U.S. credit markets would soon have impacts just as profound.

In Summary

• Emerging markets funds made it easy for western investors to invest in the Third World, and they did. As they did so, once uncorrelated emerging markets started to move in alignment with the developed world and with each other.

• They were driven by commodity prices and the U.S. credit market—all forces for synchronized moves. And they were prone to sudden withdrawals of western capital.