SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE AND IMPACT INVESTING

‘Not everything that can be counted, counts; and not everything that counts can be counted.’

Albert Einstein

Ethical and moral principles have always influenced and guided a proportion of investors and businesses. The Quakers are a good example of a religious group whose principles included opposition to slavery, alcohol and war, and support for prison reform and social justice. Quaker-founded businesses include Barclays, Cadbury, Clarks, Friends Provident, Lloyds and Rowntree, all of which had a long tradition of ethical and fair treatment of their employees and the communities in which they operated.

Increasingly, investors, both private and institutions, are questioning the impact that some businesses and their activities are having on the environment and on society. These investors do not want to support companies that are contributing to environmental degradation, or whose activities are unethical, unjust or unsustainable. More recently, the global financial crisis, increasing global inequality and clever tax planning by multinational companies have created further momentum for a reform of the way capitalism operates. Socially responsible investing (SRI), which is also known as sustainable and responsible investing, broadly refers to any investment strategy that seeks to consider both financial return and social good. There are many different types of SRI but unfortunately no clear consensus of what the myriad different terms mean (see Figure 7.1).

There is, however, consensus that there are three main advocacy issues within SRI: social, environmental and ethical (SEE risks) or environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG risks), as set out in Figure 7.2. According to the European Sustainable Investment Forum (Eurosif), SRI is implemented mainly through investment analysis, portfolio construction, shareholder advocacy and community investing. Sustainable investing is generally regarded as covering environmental, social and governance categories; ethical and impact investing fall within the social category; and shareholder advocacy falls within the governance category.

Figure 7.2 ESG framework

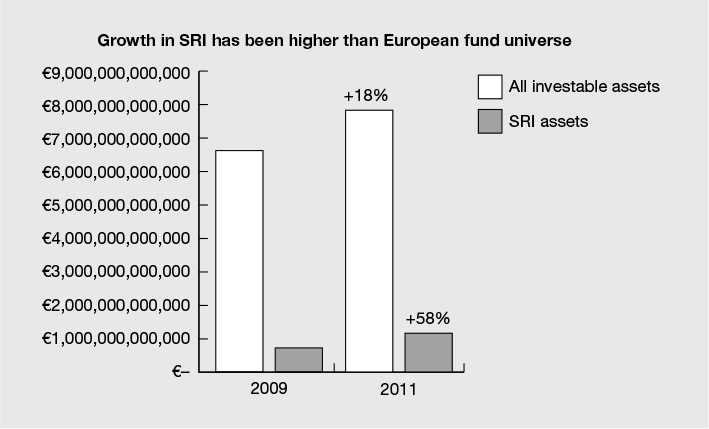

Although the SRI sector has been around in one form or another for about 100 years, it is in the past 30 years or so that it has seen the strongest growth and most innovation. An entire industry of advisers, fund managers, research groups and experts has emerged to provide appropriate investment solutions incorporating these environmental, social and ethical concerns. While SRI has been established in the US for longer, the capital invested via SRI funds is actually higher in Europe and has been growing at a much higher rate than the entire fund universe, as illustrated in Figure 7.3.

Figure 7.3 The growth of socially responsible investment in Europe

Source: Data from RBC Wealth Management and Capgemini (2012) 2012 World Wealth Report; EUROSIF (2012) ‘High net worth individuals and sustainable investment 2012’, p. 9.

In the early days of SRI, most investment solutions were solely focused on applying strict ethical criteria as an initial screen to the quoted equity market. Negative criteria means the company is engaged in an activity that does not meet the ethical screen, for example arms manufacturing, tobacco or gambling, and is therefore excluded from the fund manager’s range of permitted investments. A positive screen, meanwhile, identifies those companies that score highly on a range of desired criteria, such as combating climate change, excellent corporate governance, or providing new technology or services that have a positive impact on society. An example of positive and negative ethical screening criteria is shown in the box.

Positive criteria

Supplying the basic necessities of life, for example healthy food, housing, clothing, water, energy, communication, healthcare, public transport, safety, personal finance, education

Offering product choices for ethical and sustainable lifestyles, for example fair trade, organic

Improving quality of life through the responsible use of new technologies

Good environmental management

Actively addressing climate change, for example, renewable energy, energy efficiency

Promotion and protection of human rights

Good employment practices

Positive impact on local communities

Good relations with customers and suppliers

Effective anti-corruption controls

Transparent communication

Negative criteria

Tobacco production

Alcohol production

Gambling

Pornography or violent material

Manufacture and sale of weapons

Unnecessary exploitation of animals

Nuclear power generation

Poor environmental practices

Human rights abuses

Poor relations with employees, customers or suppliers

By its very nature, ethical (social) screening involves a high degree of subjectivity, as evidenced by this caveat in the ethical guidelines of one leading ethical fund: ‘We recognise that Stewardship’s core aim of investing only in those companies which, in what they do and the way they do it, on balance make a positive contribution to society cannot be fully captured in the policies described here. Accordingly, we may on rare occasions exclude companies which we judge conflict with that aim even when they do not fall foul of any of the negative criteria set out in this document. We may also on rare occasions where a company is considered, on balance, to make a positive contribution to society, include a company that breaches a negative investment selection criterion in a minor, inconsequential or non-material way.’1

It is essential, therefore, to carefully review the ethical filtering criteria of any ethical fund, to ensure that it does, in fact, reflect your own ethical views, because what is acceptable to one person might not be to someone else.

Thematic or trend investing

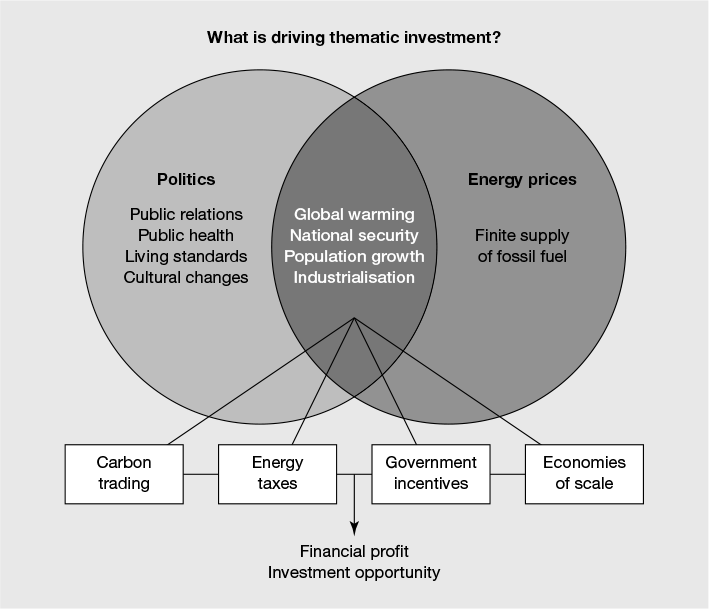

Figure 7.4 Thematic factors and concepts

Source: Blue & Green Investor.

The SRI industry has evolved over the past decade with more of a focus on thematic investing to which an ethical screen may or may not be applied. Thematic funds typically invest in companies that are meeting a specific human need, such as clean energy/water, or positioning the fund to benefit from global trends such as rising population or climate change (see Figure 7.4). The main thematic funds are water, clean energy, environment, carbon, agriculture and forestry. Some funds invest in more than one of these themes and are known as multi-thematic funds.

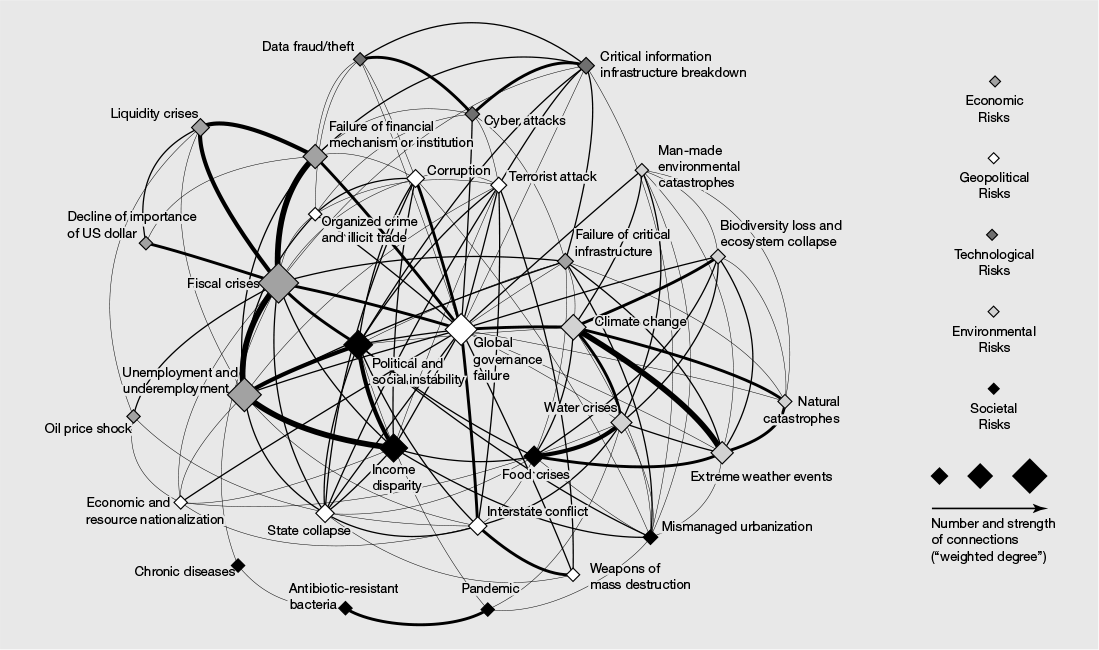

Figure 7.5 is an informative and visual representation of the various global risks to human prosperity and how they are interconnected. It is against this backdrop that thematic managers try to spot the trends, opportunities, challenges, emerging thinking and future innovations, which could avoid or reduce these risks, while also generating good financial returns for investors. The majority of thematic and multi-thematic funds focus on environmental factors and criteria when deciding how to choose investments, and this makes it easier to define, screen and measure the underlying selection criteria than an ethical fund that focuses on subjective social issues. It is interesting to note that since 2013 all UK-listed companies have had an obligation to report their greenhouse gas emissions. There are no universal standards for assessing SRI investments for a thematic fund and much of this involves labour-intensive, time-consuming and expensive research.

By their very nature, thematic funds generally have a much higher exposure to smaller companies and/or companies based or operating in emerging markets. In addition, they typically have a much smaller number of underlying securities, leading to less diversification and increased risk compared with most conventional investment funds. Unlike a traditional investment fund, where we can look at past returns and risk characteristics, it is difficult, if not impossible, to determine what the risk–return characteristics of, say, a water or clean energy fund will be.

Externalities

The body of literature on externalities is huge and even efficient markets proponents like Eugene Fama and Ken French embrace the existence of them and accept that capital markets don’t price the environmental cost of their activities such as greenhouse gas emissions, water use, land use, air pollution, land and water pollution and waste. As a result, world stock market values may well be overstated relative to what they should be, if such environmental costs were included.

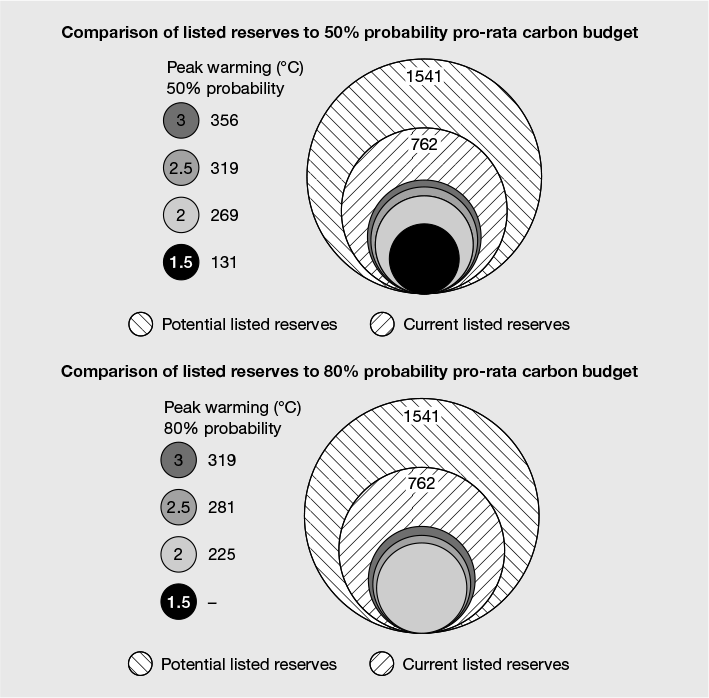

A good example of an unpriced externality is carbon. Many experts believe that the cost of releasing carbon is not correctly factored into energy companies’ costs. Research suggests that we need to hold the increase in global temperature to 2°C. This increase is equal to burning about 565 gigatons of carbon until 2050.2 However, the amount of carbon already contained in the proven coal and oil and gas reserves of the fossil-fuel companies and countries is actually almost five times as much – 2,795.3

‘Yes, this coal and gas and oil is still technically in the soil. But it’s already economically above ground – it’s figured into share prices, companies are borrowing money against it, nations are basing their budgets on the presumed returns from their patrimony. It explains why the big fossil-fuel companies have fought so hard to prevent the regulation of carbon dioxide – those reserves are their primary asset, the holding that gives their companies their value. It’s why they’ve worked so hard these past years to figure out how to unlock the oil in Canada’s tar sands, or how to drill miles beneath the sea, or how to frack the Appalachians.’4

Another recent research paper suggested that ‘a precautionary approach means only 20% of total fossil fuel reserves can be burnt to 2050’.5 This concept is shown visually in Figure 7.6, based on 50% and 80% probability of reaching various levels of warming for given levels of carbon. The researcher had this to say about the impact of carbon on the UK stock market:

‘The CO2 potential of the reserves listed in London alone account for 18.7% of the remaining global carbon budget. The financial carbon footprint of the UK is therefore 100 times its own reserves. London currently has 105.5 GtCO2 of fossil fuel reserves listed on its exchange which is ten times the UK’s carbon budget for 2011 to 2050, of around 10 GtCO2. Just one of the largest companies listed in London, such as Shell, BP or Xstrata, has enough reserves to use up the UK’s carbon budget to 2050. With approximately one third of the total value of the FTSE 100 being represented by resource and mining companies, London’s role as a global financial centre is at stake if these assets become unburnable en route to a low carbon economy.’

Figure 7.6 Unburnable carbon – listed carbon reserved compared with climate change maximum useable

Source: Carbon Tracker.

The majority of institutional investors and a minority (but growing) proportion of individual investors invest significant amounts in passive funds that track the UK and international stock markets. An even larger proportion invests in actively managed investment funds that are benchmarked against market indices. So, one way or another, most investors have significant exposure to companies that are valued on the basis of huge fossil fuel reserves, which may never be possible to use.

As we explored in Chapters 5 and 6, finance theory suggests that capital markets do a good enough (although not perfect) job of pricing risk and as such current prices should reflect all known information. If this is the case, how can it be that the world’s brightest and cleverest people working in investment banks and fund management companies are not pricing the externalities associated with energy companies’ assets which, based on the science, they can never use? Experts in this field have suggested various theories, but perhaps the main one, which intuitively might make sense, is the fact that the investment world is using flawed valuation metrics based on outdated business and economic models, and that have not been adapted to the new environmental reality.

Implications for investors

In my view there seem to be five possible approaches you could adopt to deal with the various externalities that investment markets don’t or can’t factor into current securities prices:

- Maintain a traditional unfettered passive investment strategy and allocation, rebalancing as necessary in the light of market movements, on the basis that any repricing of risk will happen gradually over time and eventually be reflected in world stock market values.

- Overweight the portfolio to thematic and multi-thematic funds that focus on alternative energy, forestry, clean water and other trends connected with the environment.

- Allocate capital to private equity that invests in renewable energy and other innovations such as carbon capture and storage.

- Invest in a passive portfolio that applies a sustainable investment screen.

- Do a mixture of 1–4.

Before you decide on your approach we need to consider the potential role of a more recent innovation in the world of investing, that of sustainable investing.

Sustainability

While ‘sustainability’ may have different meanings to different people, the term is often associated with general concern for the environment. The United Nations describes sustainable development as ‘development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’.6 With this framework in mind, business practices that exhaust resources or cause irreversible changes to the earth’s climate are considered unsustainable.

Sustainable investing is different from other types of SRI because it uses much more objective screening criteria, based on measuring, rating and ranking the things that scientific consensus identifies as being important to sustainability. Examples7 of business practices that relate to sustainability include the following:

- Reducing resource consumption: sustainable companies are efficient in their use of natural resources – particularly non-renewable resources and energy that contribute to global climate change.

- Reducing emissions of toxics and pollutants: companies that emit harmful chemicals, break environmental laws or show wanton disregard for local environments are not performing sustainably.

- Implementing proactive environmental management systems and initiatives: embedding environmental thinking into the business structure maximises sustainability thinking at every point, rather than only after the fact.

- Helping customers achieve sustainability: thinking beyond the walls of the company to design products that reduce the environmental impacts during product use is key to sustainability.

With these business practices in mind, it is then possible to develop a screening process and apply this to the universe of equities and/or bonds to determine which holdings are sustainable. There are various ways that the sustainability screening can be done but the approach of one leading investment manager is shown in the box.

Rank companies within industries on these factors:

- Climate change variables – 30% weighting

- Sector-normalised CO2 emissions intensity

- Climate change solutions users

- Climate change reporting

- Environmental vulnerability variables – 35% weighting

- Hazardous waste

- Environmental regulatory problems

- Toxic emissions

- Environmental controversy

- Environmental negative economic impact

- Environmental strength variables – 35% weighting

- Environmental management systems

- Pollution prevention

- Recycling

- Environmental initiatives

- Beneficial products and services

- Overweights: those that score above average

- Underweights: those that score below average

- Excludes the worst 10% in each industry

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors Inc.

Expected returns – market versus sustainable portfolio

Having applied a sophisticated sustainability filter to the universe of securities, we then need to ask ourselves what impact, if any, this will have on expected returns compared with investing without the filter. Factors that suggest higher expected returns from a sustainable portfolio include the fact that such firms are better prepared for the future, will profit as more consumers make green choices, and have lower risk exposures to disaster, regulations and negative PR. Factors that suggest lower expected returns from a sustainable portfolio include the fact that this type of investing is more costly to research and implement, many companies might package themselves as green but are far from being truly sustainable in reality, and, if sustainable firms are lower risk, they must by definition deliver lower returns.

On balance it would seem that the return enhancing and reducing factors balance themselves out and the expected returns from a traditional and a sustainable portfolio should be broadly similar. However, there are explicit and implicit costs involved in SRI in general, not just sustainable investing. Explicit costs relate to the research and screen process so the total ongoing cost of SRI funds might be higher than that of non-SRI funds. Implicit costs relate to the opportunity costs arising from the screening process excluding companies that might have higher realised returns. In addition, because the universe of companies that the fund holds is smaller, there is some reduction in diversification, leading to a slight elevation of risk. These elevated costs suggest that if the expected return of a traditional portfolio is broadly the same as a sustainable portfolio before costs, then after costs the sustainable portfolio must, by definition, deliver a slightly lower return. The differential is unlikely to be large in relation to achieving one’s financial goals, but seems to be the price one needs to pay to invest on a sustainable basis.

Research into SRI has been going on for many years. An analysis of 68 SRI academic studies published between 2000 and 2012 suggests that the empirical evidence presents a rather mixed bag.8 About 44% were positive, 18% were negative, 32% were neutral and the remaining 6% were mixed between neutral to negative and neutral to positive.

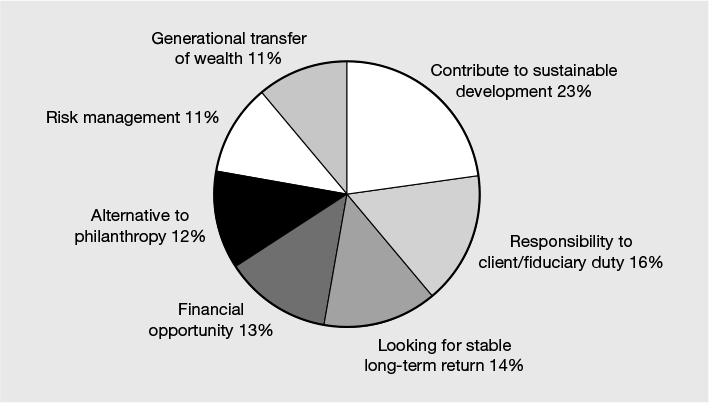

A 2012 study of high net worth individuals suggests that people invest sustainably for varied reasons beyond simple fear and greed and their motivations are not just economical but also involve deeper values that are important to them.9 These are set out in Figure 7.7. If you share any of these views, it may well be appropriate for you to invest your portfolio partly or wholly on a sustainable basis.

Figure 7.7 Reasons for investing sustainably

Source: EUROSIF (2012 ) ‘High net worth individuals and sustainable investment’.

Social impact investment

‘Social investment enables social goals to be achieved via engagement with projects which feature recognisably commercial elements. Unlike charitable donations, the funds are potentially recyclable.’

Gavin Francis, founder, Worthstone Limited

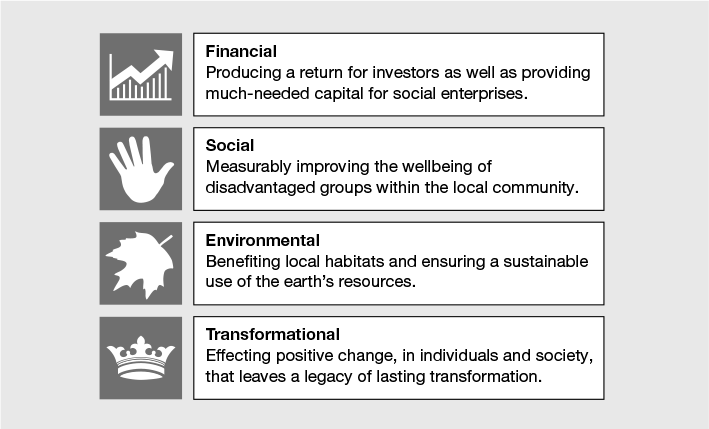

Social investment, or impact investing as it is more widely known in the United States, is the provision of finance to charities and other social organisations to generate both defined and measurable social and financial returns. Unlike traditional charitable giving, however, the capital is an investment, not a donation, and as such social impact investors expect at least a return of their capital, as well as good social outcomes. Figure 7.8 summarises the key elements of social impact investments.

Figure 7.8 Social impact investment factors

Source: Worthstone Limited.

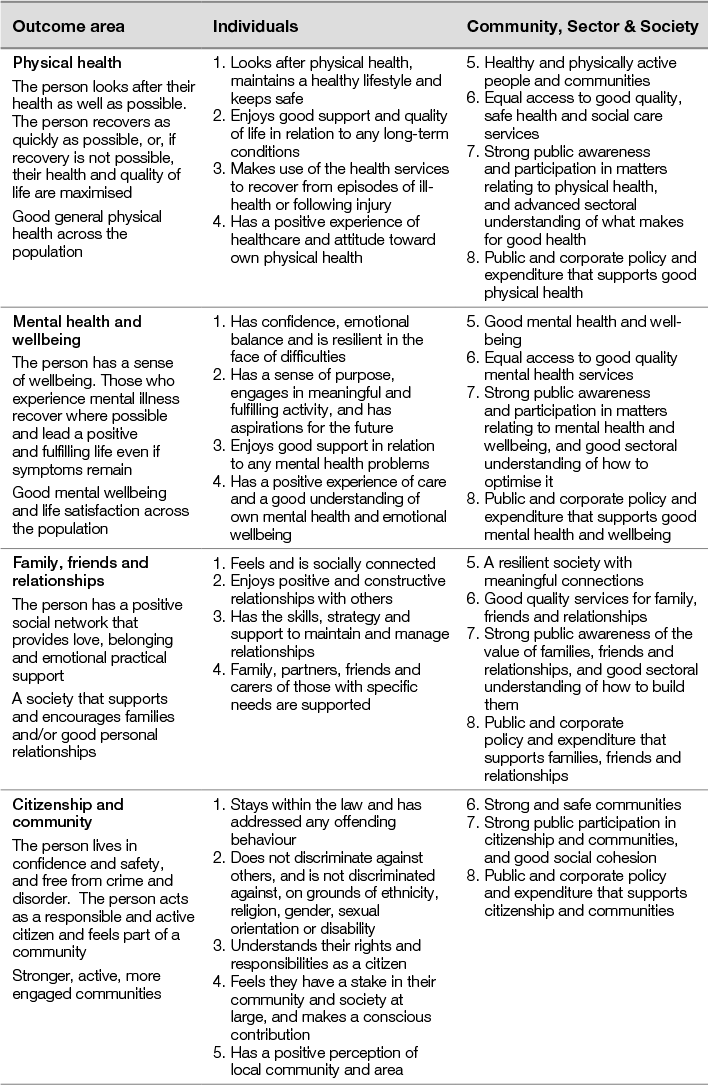

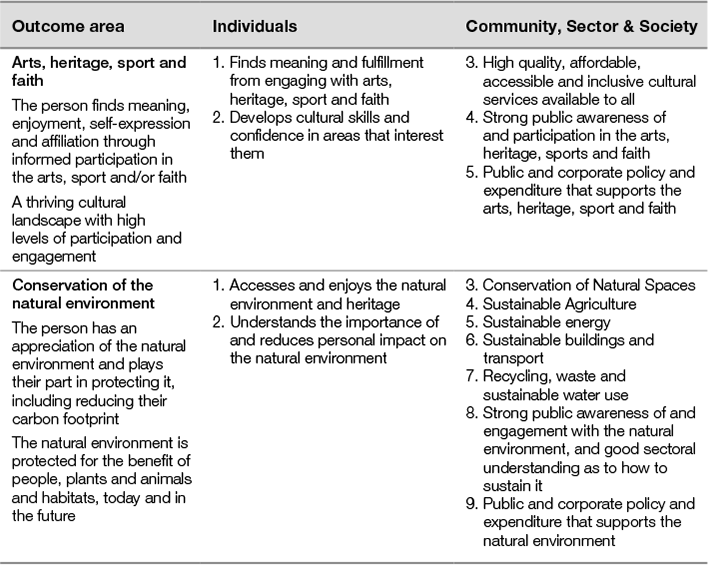

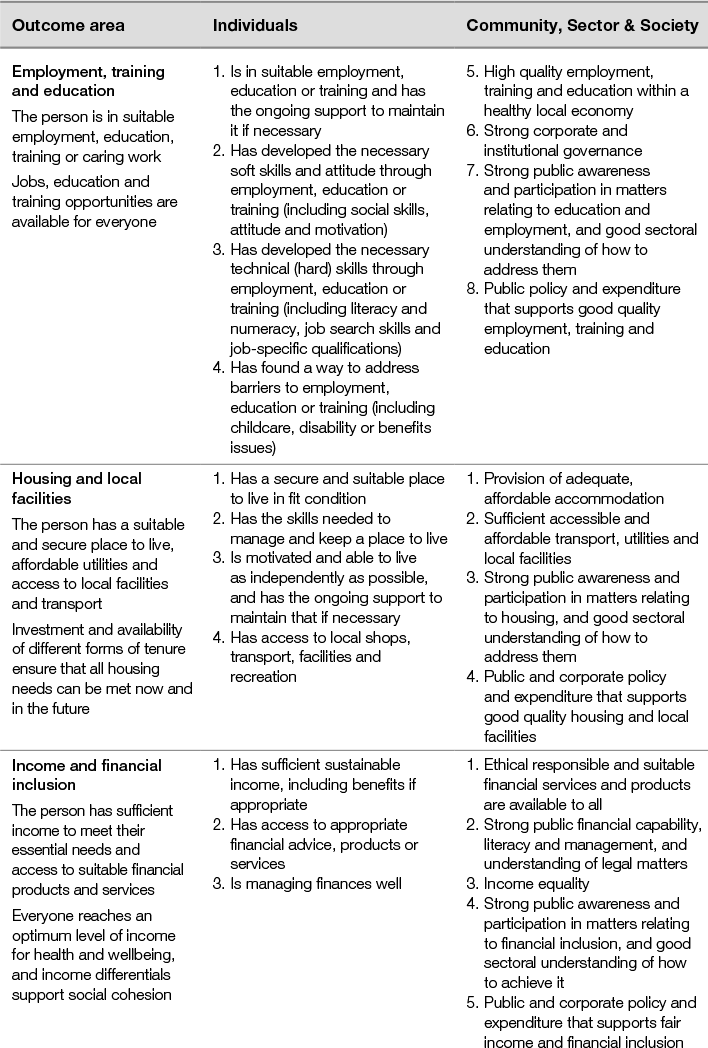

The range of possible social outcomes is wide and these outcomes are summarised in Table 7.1. It is essential, therefore, to ensure that you invest in an activity with a social outcome that matches your own values and concerns.

Source: Big Society Capital Outcomes Matrix 2013, developed in partnership with New Philanthropy Capital, the SROI Network, Triangle Consulting and Investing for Good.

Social impact financing can take the form of short- or long-term loans, preference type share funding, or long-term committed equity such as capital. Such finance might be used to fund:

- asset purchase (i.e. property and plant)

- working capital (i.e. cashflow)

- growth capital.

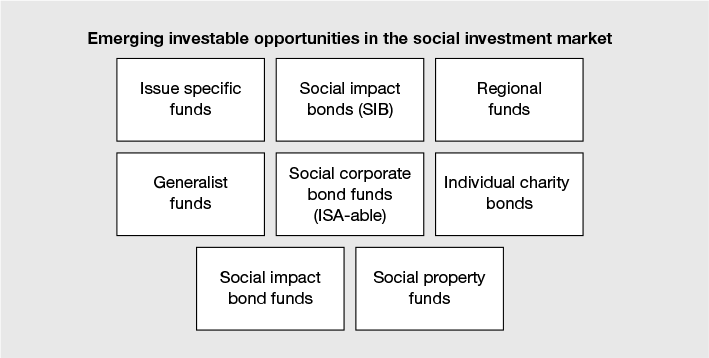

Charities and social enterprises repay the loan capital with interest and the investor is then able to reinvest in other projects to multiply the social impact of the original investment. Clearly not all loans will be repaid, but, if you invest in a reputable social investment fund, the manager will carry out thorough due diligence so that loans are made only to well-managed organisations with sound business plans. Alternatively, you could research individual social impact investments yourself, but if you do this, avoid putting too much in any one holding. Figure 7.9 shows the range of social impact investments available at the time of writing.

CAF Venturesome was one of the first social investment funds set up to support UK social investment. The fund provides loan capital to charities, social enterprises and community groups so that they can deliver services that have a high social impact. However, an increasing number of social impact and micro-financing opportunities have started to emerge over the past few years. UK social investment was given a big boost in April 2012 when the UK government set up Big Society Capital, to make finance available to organisations tackling major social issues. Big Society Capital has £600 million to invest in a range of social investment intermediaries, which then lend on to charities and social enterprises.

Most social impact investors understand that the bulk (if not all) of the return is likely to be in the form of a positive and tangible gain for society. When the capital is eventually returned to the investor by the social enterprise (with or without any financial return), the investor is then free to recycle the capital into new social investments. However, because social impact investments now also qualify for generous tax benefits,10 just obtaining a return of capital after three years would still represent an annualised return of in excess of 10% just from the initial tax relief. See Chapter 14 for a worked example of how combining income tax and capital gains tax deferral and staggered encashment of a social investment, merely with a return of capital, could generate a cash uplift of circa 100%, equivalent to an internal rate of return of 25%.

Social impact investment can be done instead of or in addition to charitable giving, although I would encourage you to do both, because they meet different funding needs. My experience is that where someone was previously not keen to do any, or increase existing, charitable giving, they will often consider making social investments because they don’t perceive that it is ‘dead’ money, never to be seen again. It seems that for some people, the act of choosing and following the progress of a social impact investment makes them feel more engaged with the social impact objective.

Making good and doing good

By Norma Cohen

Suzanne Biegel’s story is probably typical of that of most active social investors. She started her career at IBM in the late 1980s and 1990s. The business she built and sold, IEC, was an e-learning business that she ultimately sold to a larger company. In 2000, she found herself living in California and wealthy, but looking for new challenges.

She devoted herself to organisations focusing on her passions: the environment, social and economic justice and the status of women and girls. She actively campaigned for ‘change not charity’ after selling her business.

But, like many who find themselves drawn to social investment, she grew dissatisfied. “Fundamentally, I’m a business person,” she says.

In the US, what is known as “impact investing” has been around for 20 years and is modelled on what are known as Theatre Angels, wealthy private individuals who are prepared to take a risk on stage productions. As in the UK, it is most likely not to pay off, but when it does, the returns can be spectacular. But most importantly, the investors gain close engagement with the production and earn their rewards in part by promoting theatre to the world at large.

So it is for social impact “angels” who often are successful entrepreneurs themselves and offer their particular skills to fledgling businesses. Biegel said she is seeking returns “in double digit returns” but often finds that she does better than that.

Peter Wilson, a director of Omnia, a legal firm, had a background in diplomacy and international development and established himself as a post-conflict stabilisation specialist, overseeing projects in countries such as Iraq. After leaving public service, he set up his own consulting firm.

“It grew from a bunch of guys working out of my bedroom to a growing business,” he says. When it was sold to a larger firm, Wilson had money to invest.

While most of his investments are “arm’s length” – held purely to deliver returns – he has also made social investments. Currently, he holds stakes in five social enterprise companies. “I’d be looking for a rate of return similar to that on conventional companies,” says Wilson.

But for those companies he becomes engaged with, there is another form of payback: intellectual challenge. “I am not at the stage where I can just give away money. But when I set up my first company, we watched things that were intellectual things.” Keeping that up, he says, is important to him.

Jonathan Adams, a fund manager at Investec, had been an investor in “angel” companies for years, although none had social objectives. But three years ago, his employer offered him a chance to mentor a company, JuJu films, supported by the Bromley-by-Bow Centre, a charity founded by renowned social entrepreneur Lord Mawson.

That opened his eyes to the possibility of social impact investment. “I do have a target rate of return,” Adams says. “I just haven’t quantified it. You’re willing to bear a lower target return across the portfolio.

“If you’re looking for zero return, you are right at the charitable end of things,” he adds.

![]()

Source: Cohen, N. (2013) Making good and doing good, 23 March 2013.

©The Financial Times Ltd 2013. All Rights Reserved.

SRI in context

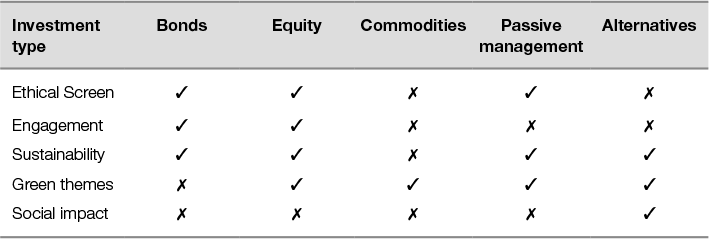

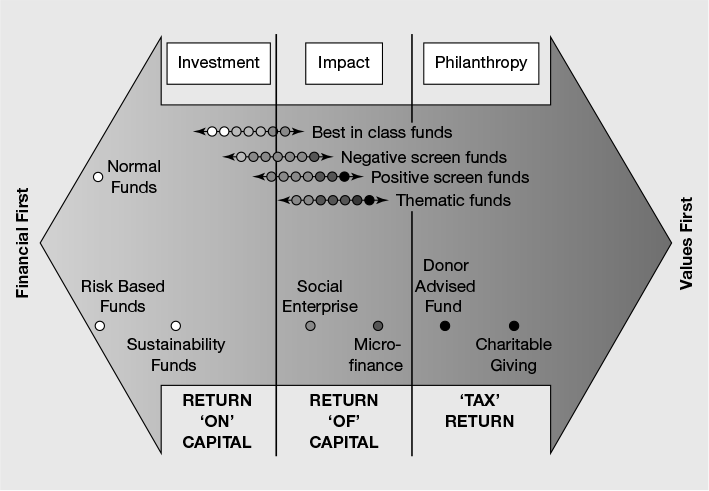

As we’ve seen, SRI covers a wide spectrum of investing styles, risk–return profiles, values/beliefs and solutions. Whether you want to invest some or all of your money in SRI, there is now a wide range of investment solutions which can enable you to reconcile any deeply held views, beliefs and values with the need to invest your wealth to achieve your financial goals (see Table 7.2). However, it’s also important to be totally clear about where the different types of SRI sit in the context of your overall wealth plan in general and your investment strategy in particular. This is because they all deliver different things and there is a big difference between SRIs that seek to offer a return on your capital, a return of your capital or just a tax incentive. Figure 7.10 will help you to understand how the different SRIs fit across the ‘money for purpose’ spectrum. You’ll notice that this includes philanthropy, so in Chapter 24 we’ll look at the role of philanthropy and why and how this might fit within your overall plan.

1 Friends Life, ‘Stewardship criteria & policies’ p. 2.

2 Meinshausen, M., Meinshausen, N., Hare, W., Raper, S. C. B., Frieler, K., Knutti, R., Frame, D. J. & Allen, M. Greenhouse gas emission targets for limiting global warming to2°C. Nature, doi: 10.1038/nature08017 (2009).

3 Leaton, J, ‘Unburnable Carbon 2013: Wasted capital and stranded assets’ – Carbon Tracker (2013).

4 Rolling Stone – ‘Global Warming’s Terrifying New Math’ Bill McKibben 12.08.12.

5 Ibid footnote 3.

6 United Nations (1987) ‘Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development’, General Assembly Resolution 42/187, 11 December.

7 Sustainable Holdings & Esty Environmental Partners, Environmental Sustainability Ratings.

8 Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors Inc. 2013.

9 EUROSIF (2012) ‘High net worth individuals and sustainable investment’.

10 Since the 2014/15 tax year social impact investments benefit from virtually the same tax benefits as for enterprise investment schemes (EIS).