KNOW WHERE YOU ARE GOING AND WHY

‘Happiness is not having what you want, but wanting what you have.’

Hyman Schachtel, US rabbi

Many people go about planning and managing their wealth in a haphazard and random manner. They have a vague idea of what they want, gain some information and go from one financial solution to the other, without any real plan or context. Over the years I’ve answered many readers’ questions for the Financial Times and other weekend newspapers and a common question is: ‘How should I invest my capital?’ This is the same as asking: ‘How long is a piece of string?’ The answer is: ‘It depends.’

Viktor Frankl, in his classic book Man’s Search for Meaning,1 wrote about his observations of human motivation when he was held in a Nazi concentration camp. His central observation was that ‘a man can always find the “how” if he knows the “why”’. Before you can go about making good financial decisions you need to know your ‘why’.

The key to a successful wealth plan is setting personal life goals and objectives in the context of your money values. In addition, agreeing and articulating overarching financial planning principles will assist with future decision making.

Money values

Abraham Maslow was a psychologist who developed the theory of ‘the hierarchy of needs’, which provides a basic framework for all human motivation and associated actions. At the bottom of the ladder are basic needs such as food, shelter, sex, etc. Once these basic needs have been met the individual will seek to fulfil higher-level needs that serve to meet their wider personal desires, such as friendship, love, material possessions and status. Once these intermediate needs have been met, an individual will seek much higher-level needs, which at their highest level are known as ‘self-actualisation’. These needs generally relate to wider society and the desire of the individual to find their real meaning or place in the world.

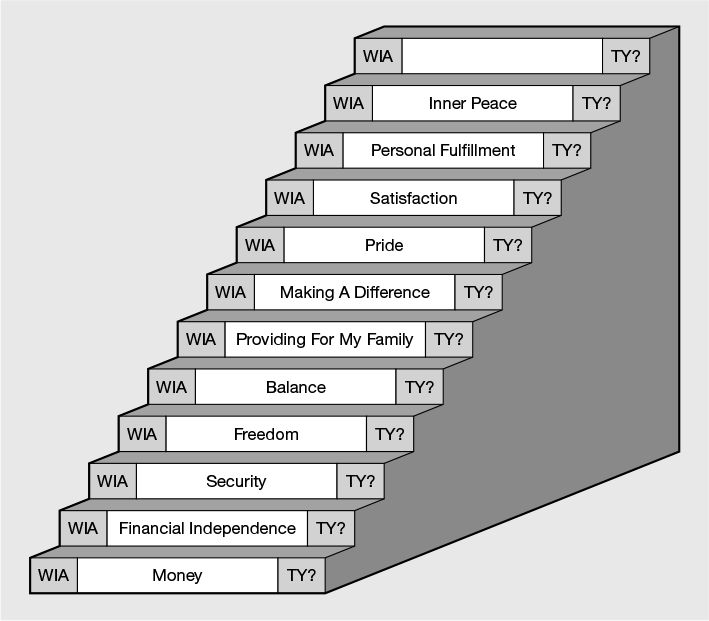

The self-actualisation stage is where real meaning and contentment can be found. For many people this concept of self-actualisation can appear a bit woolly or vague, even frightening. We can adapt Maslow’s ideas to help us make decisions that are in tune with our ‘money values’. Money values are overarching beliefs that you have about money and these follow a progressive hierarchy. The ‘values conversation’, as it is known, starts with asking the question: ‘What’s important about money to you?’ (See Figure 1.1.) This approach was pioneered by Bill Bachrach in his excellent book Values-based Financial Planning2 and this forms the basis of the training that his company provides to progressive financial planners.

Figure 1.1 The values staircase: what’s important about money to you?

Source: The Values Conversation® and The Values Staircase® were excerpted from Bill Bachrach’s Valuesbased Financial Planning book. It is provided courtesy of Bill Bachrach, Bachrach & Associates, Inc., www.BillBachrach.com ©1996–2011 Bill Bachrach. All rights reserved.

Usually the first response to the question ‘What’s important about money to you?’ will be general and basic answers such as ‘financial security’, which is a perfectly reasonable response. However, if you keep following this line of questioning with ‘And what’s important about financial security to you?’, it will allow you to discover more deep-seated values. It is this process of self-actualisation that helps us to find real meaning and purpose for the future wealth plan. Some people find this process a bit uncomfortable as it requires a level of reflection and contemplation about money that we rarely give to it. However, this reflection can be highly liberating and might allow you to develop a better sense of priorities and objectives.

Life planning can give deeper meaning to goals and dreams

Over the years I’ve met many financially successful people who have stopped dreaming. They have ‘switched off’ from identifying real meaning, purpose and authenticity in their life. It is not uncommon for a business owner to work hard for years, sell their business for a significant sum and then lose all purpose in their life. This is because their central focus, their business, has been taken away. They then drift along slowly losing motivation and purpose. Other times they jump straight from the sale of their business to ‘investing’ some of their hard-won capital into a new business venture, only to see the business, and their hard-earned capital, slowly dwindle to nothing.

When I was looking for ways to help my clients to envisage a better future and to articulate their life goals and objectives, as well as to improve my own happiness and life meaning, I discovered life planning. In essence, life planning is about living life on purpose, whatever that means to you. George Kinder is considered by many to be the father of life planning and his ground-breaking book, The Seven Stages of Money Maturity,3 sets out a radically different way of approaching managing wealth. I attended a training workshop during one of George’s regular trips to the UK a few years ago, and I found it very enlightening as it made me question a number of my principles and ideas about my life and the role that money played in it. A consequence is that eventually I realised how much was ‘enough’ and what was really important to me.

The three difficult questions

A key element of the Kinder approach is to ask yourself three difficult questions.

- Question one. I want you to imagine that you are financially secure – you have enough money to take care of your needs, now and in the future. The question is, how would you live your life? What would you do with the money? Would you change anything? Let yourself go. Don’t hold back your dreams. Describe a life that is complete, richly yours.

- Question two. This time, you visit your doctor who tells you that you have five to ten years to live. The good part is that you won’t ever feel sick. The bad news is that you will have no notice of the moment of your death. What will you do in the time you have remaining to live? Will you change your life and how will you do it?

- Question three. This time, your doctor shocks you with the news that you have only one day left to live. Notice what feelings arise as you confront your very real mortality. Ask yourself: ‘What dreams will be left unfulfilled? What do I wish I had finished or had been? What do I wish I had done? What did I miss?’

The purpose of these questions is to help uncover your deepest and most important values. Equally important is uncovering what is standing in the way of leading the life that is truly the one you want to live. In this context, another home or expensive car might not be the answer.

What’s really important?

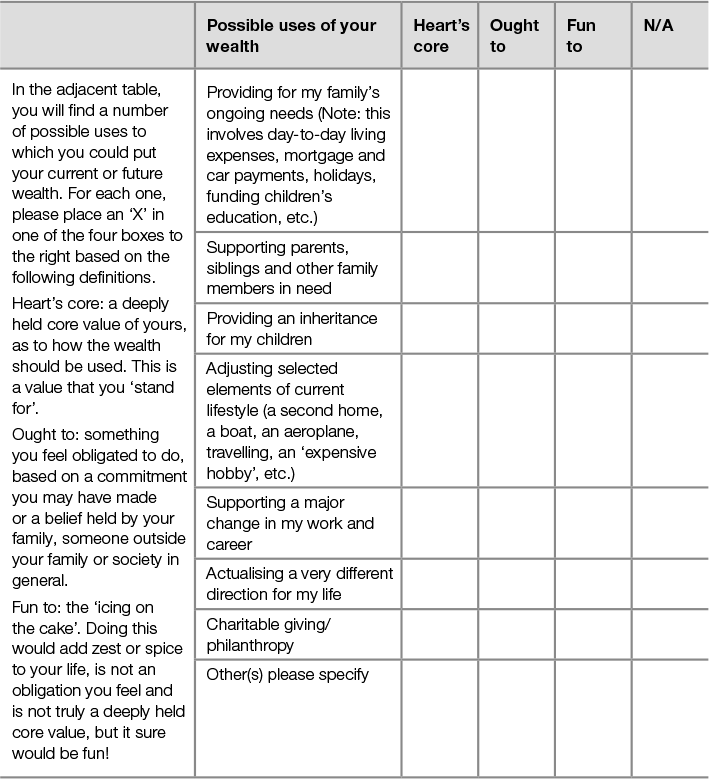

Kinder sets out a framework for helping us identify what is really important in life. The values grid, as it is known, determines between ‘heart’s core’ – what really matters; ‘ought to’ – things that you feel obliged to do; and ‘fun to’ – irreverent things that aren’t really important but nevertheless are possible goals. (See Table 1.1.)

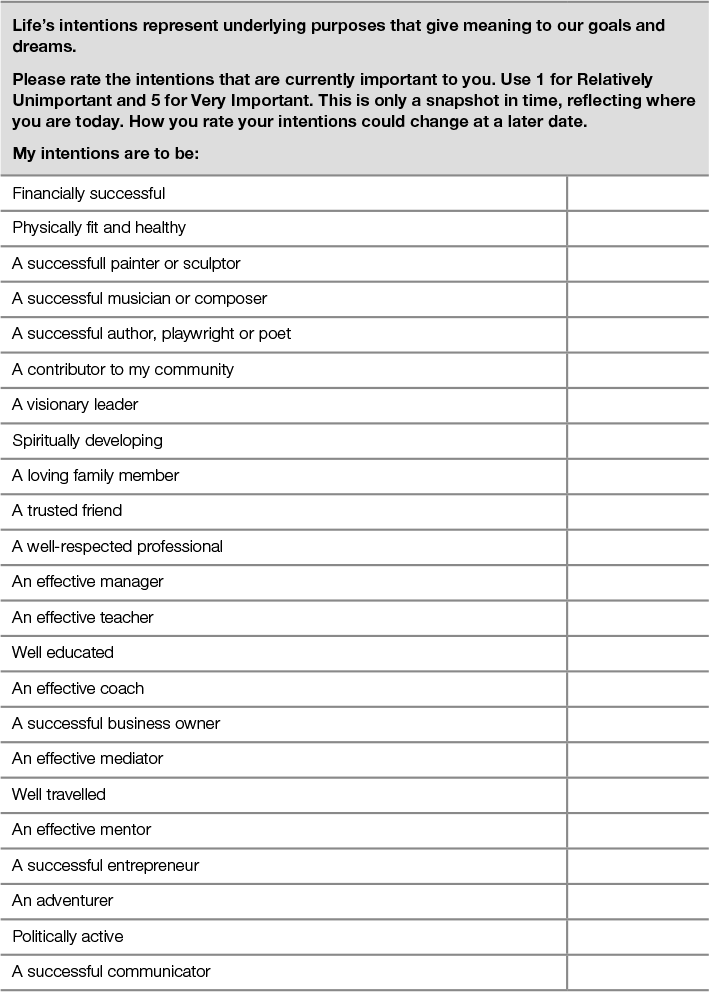

Life can seem complicated, things get in the way and we sometimes do things we would rather not do and don’t do the things that we would rather do. Maria Nemeth is a clinical psychologist and a Master Certified Coach. Maria asks her clients: ‘Would it be OK if life got easier?’ Maria has developed a useful tool called the Life’s Intentions Inventory and this is reproduced in Table 1.2. Why not take some time now to go through the inventory and score the relative importance of each of the intentions. You might find it quite enlightening and it might make you rethink what’s important to you and why.

Table 1.1 The values grid

Source: Adapted from the Kinder Institute of Life Planning, which trains Financial Life Planners all over the globe using the EVOKE Client Interview process. Reproduced by kind permission of George Kinder and the Kinder Institute of Life Planning. www.kinderinstitute.com

Financial planning policies

Once you have uncovered your purpose, motivations and money values, you can then use these to help you to formulate financial planning policies. Financial planning policies are tools for making good decisions in the face of financial uncertainty. They transcend the current situation by expressing, in general terms, what you plan to do and how you are willing to do it in terms not limited to the current circumstances. Such policies are broad enough to encompass any novel event that might arise, but specific enough so that we are never in doubt as to what actions are required. We’ll see the value of having planning policies in Chapter 12 when we discuss withdrawal rates from an investment portfolio.

Examples of financial planning policies include:

- I will give 10% of my gross annual income to charity.

- I will only do work that I love.

- I will maintain sufficient life insurance to cover my children’s education costs.

- We will provide family members with financial literacy support but will not give them money.

- I will not invest in any investment or tax planning that I do not understand.

- I will invest only in ‘positively screened’ ethical investments.

- I will delegate everything in relation to my finances either that I do not enjoy doing or that can be done by someone else at lower cost, taking into account the value of my time to be able to do other things.

- I will always maintain a minimum of one year’s living costs in cash and if my portfolio falls more than 20% in a 12-month period then I will reduce the amount of regular withdrawal I take to 50% for up to 2 years.

- I will invest only in socially responsible funds.

Financial policies are the anchor points of your strategy to help decision making in difficult times or where there are competing objectives. Think of the policies as the keel of your financial boat, keeping you from capsizing in rough financial seas.

Clear goals

There is something incredibly enabling about defining and writing down clear life goals. Notice that I refer to life goals, not financial goals. My view is that people don’t have financial goals, they have life goals that have financial implications.

In 1961 President Kennedy set the incredible goal of sending a man to the moon and safely returning him before the end of the 1960s. He didn’t tell the NASA people to see what they could do in space over the next few years and come back to him with a few achievements; Kennedy was specific about what he wanted and had a clear timeline. In my experience, people who have clear and realistic life goals tend to make better financial decisions.

Life goals that will be common to everyone are maintaining financial independence and staying fit and well. This means being able to fund your desired lifestyle until you die, regardless of your desire or ability to work, and that your money lasts a lifetime, including a time when paid work is optional as you have enough financial resources available to fund your desired lifestyle. If you work for money, you do so because you want to, not because you have to. The term ‘financial independence’ is much more meaningful to people today than the concept of ‘retirement’ and is something worthwhile to aim for. This is because, unlike retirement, which for some people means a time of doing nothing but playing golf or gardening, financial independence means you have the choice of doing whatever you wish.

The four key factors that will affect this objective are how long you live, how much you spend, the return you achieve on your capital and the rate at which the cost of living rises. We’ll cover these issues in more depth in Chapter 3 and determine what are reasonable assumptions to use when formulating your overall plan.

Clearly, your lifestyle, genetics and sense of purpose will play a large part in determining your standard of health, but if or when your health deteriorates, you’ll want to make sure that you can afford any additional costs for health and long-term care and continue to enjoy a good quality of life. With people living longer and continual advances in medical treatment, the importance of planning for declining health will affect more and more people. Life expectancy in the UK has been rising for many years and some commentators have described 90 as the new 70. But life expectancy isn’t the only issue that you need to factor into your plans – quality of that life is also important because it can have significant cost implications.

Other goals

There may be any number of other goals that are important to you. The following are real-life examples that I have come across in my work with clients. Some have more of a financial implication than others, but it is important to get the goals written down so that you can get excited about pulling together your wealth plan:

- funding part or all of the education costs of a child, grandchild or other family member or friend

- leaving a specific legacy to an individual or charity

- funding the cost of your child or your adult child’s wedding

- taking up a hobby, such as sailing, shooting, scuba-diving or flying, which has a cost implication

- taking up further study or further education at a university or college

- mentoring young businesses and possibly providing development funds

- indulging an interest in culture such as opera, ballet, musicals or performance art at home and abroad

- learning a foreign language and staying in the relevant country for some time

- buying a second home in the UK or abroad

- moving abroad to live permanently

- helping your children or other family members to buy their first home

- setting up a small ‘lifestyle’ business such as a country pub, restaurant or shop

- travelling around the world to indulge an interest in historical buildings and/or interesting places

- learning a new skill such as dancing, martial arts or rock climbing

- buying a boat, classic car or plane

- collecting art or other items

- buying an expensive musical instrument

- visiting relatives more often, particularly those living overseas

- writing a book (take it from me, it’s not easy).

While setting clear life goals is essential to developing a wealth plan that works, not all goals are of equal importance. I have found it helpful in my own planning and when working with clients to categorise goals in order of importance. Goals are therefore ‘required’, ‘desired’ or ‘aspirational’.

Required goals

The ‘required’ goals are the most important and must be met come what may – they are non-negotiable – and will usually revolve around maintaining financial independence throughout your lifetime and remaining fit and well or obtaining treatment and care to enable you to have a high quality of life. You should state the minimum annual lifestyle cost that you would be prepared to accept – your basic financial independence target – in the event that things such as taxes, investment returns or inflation turn out worse than you expect. There may be other goals like funding school fees, which are equally important and must be met but for which you could substitute a cheaper option as a base scenario.

Desired goals

‘Desired’ goals are important but not at the expense of the required goals. You might, for example, wish to fund a slightly more expensive lifestyle than that assumed under the required goals. Examples of other typical desired goals might include making regular gifts each year to individuals, a trust or charity; preserving assets for your children; investing in a new business; or funding a holiday home. In essence, desired goals are important and broadly reflect the middle values in the values staircase in Figure 1.1. They usually, but not always, reflect a desire to help the wider family.

Aspirational goals

‘Aspirational’ goals are essentially those goals that you wish to achieve if everything else has been catered for and perhaps investment returns have been consistently above those assumed or you’ve spent less than anticipated. Such goals often reflect the desire to help wider society. Such ‘aspirational’ goals might be giving money, time or both to good causes in your lifetime or after death. The point is that if the investment strategy has produced returns below the original assumption, it is the aspirational goals that take the back seat, not your core lifestyle expenditure.

Philanthropy is a possible example of an aspirational goal, although it may be the quantum of philanthropy rather than the act. For example, you might have a ‘required’ goal to support a charity or cause with time or modest financial gifts, whereas you might have an ‘aspiration’ to give much more substantial amounts of money if you are able to do so.

Example

The unhappy surgeon

Many years ago, at a financial planning conference in the United States, I heard the following story that illustrates how we can think differently about work and ‘retirement’, sometimes with life-changing consequences.

A well-respected and ostensibly successful surgeon, let’s call him Mr Jones, visited a financial planner. During the initial goal-setting discussion the planner gently asked Mr Jones what his key concerns were. Mr Jones revealed that he really didn’t enjoy his job any more; his relationships with his wife and 13-year-old daughter were under strain; he had high blood pressure and suffered bouts of depression, for which he was on medication. In addition, Mr Jones, despite earning a high salary and having built significant wealth, didn’t feel wealthy or successful.

Mr Jones’ plan was to work hard for the next five years and earn as much as he could so that he could afford to ‘retire’ to Florida and have enough time for both his wife and daughter and his other hobbies like fishing and cycling, neither of which he currently had time to pursue. The planner took all this in and suggested that Mr Jones come back in a few weeks, once the planner had been able to run the numbers and see whether this would work.

Mr Jones duly returned a few weeks later. The planner showed a picture of Mr Jones’ overall wealth and confirmed that the numbers did seem to support the strategy that Mr Jones was currently pursuing. However, the planner pointed out that with the current approach Mr Jones would continue to be unhappy over the next five years and possibly find that he might not survive long enough to enjoy his life when he stopped work.

The planner then showed another picture of Mr Jones’ wealth that was also sustainable. In this alternative scenario Mr Jones would actually work about half his current hours, with immediate effect, but instead of stopping work in five years he would work at the new reduced rate for the next ten years and an even more reduced sum for the following five years. The planner explained that the benefits of this approach were that Mr Jones could do surgery, which he really enjoyed, he would have enough time to spend with his wife and daughter and pursue his hobbies now, and he would be able to schedule exercise and rest. Mr Jones had not considered this alternative approach and cautiously agreed to give it a try.

At the progress meeting with the planner about a year later, Mr Jones explained that he was really enjoying his work again, and the paradox of making himself less available meant that his value went up and he was almost earning the same income working 2.5 days a week as when he was busting a gut working 6 days a week. His blood pressure was now under control and he had lost about a stone in weight. His relationship with his wife had improved considerably and while no amount of planning could change the fact that his daughter was a typical teenager, with all the usual associated challenges, he felt much more able to understand her and flew off the handle far less.

The message here is that thinking differently about the big-picture plan could, quite literally, save a life.

Time horizon

Different goals will require different approaches based on whether they are short-, medium- or long-term goals. Funding a wedding or house in a couple of years will mean that the need is to avoid the potential for capital loss; inflation is less of a concern. Funding your long-term lifestyle, however, means that inflation will be more of a threat and therefore you could accept some risk to capital in return for the potential of generating real returns over the long term.

Current/desired lifestyle expenditure

The clearer you can be about what your current and future lifestyle costs are, the better your overall plan and associated financial decisions will be. This is because funding your lifestyle will have an influence on your investment strategy, tax planning and wealth succession planning. In my experience, the vast majority of people rarely have a clear idea of the cost of their current or desired lifestyle and they consistently underestimate how much they are spending. Sometimes this is because they feel guilty about how their expenditure. In other cases the attributes of their personality that helped them create their wealth may not be those required to manage it well. Entertainers are a classic example of individuals who have high earning capabilities but often have poor financial judgement. Elvis Presley was well known for being generous and gave Cadillacs to strangers. Who knows how much Elton John has spent on flowers over the decades?

Over the years I’ve had clients tell me: ‘This was an exceptional year for spending.’ Every year seems an exceptional year! Do remember to account for things such as holidays and home improvements/maintenance. The importance of having a clear idea of expenditure, both now and in the future, will vary from person to person depending on the financial resources they have available. My advice is to be realistic about what you will spend throughout your lifetime as it is better to overestimate than to underestimate. There is no need to spend lots of time doing detailed budgets, just as long as you are totally confident that you have a true idea of how much you really are spending (or would like to spend).

Don’t mention the ‘R’ word

If you are thinking about retirement as a goal, I suggest you ask yourself the following questions to see whether that really is the goal for which you are aiming.

- What does retirement mean to you?

- How will you live your life differently when you are retired?

- Do you have a role model of someone who is retired and, if so, what is it about their lifestyle that you admire?

- Do you have concerns about retirement and, if so, what are they?

- How would you feel about working less but for longer?

‘For many, a conventional retirement may not be welcome. More than ever before, we are enjoying good health to an older age and many of us are not only capable of working well beyond retirement age, we also often have the desire to do so. Today’s older generation can often be found using their retirement years to start a new career, set up a business or to consult in their specialist field. As a result, the notion that an individual should cease working at a pre-defined age is more of an illusion than a reality.’4

People who have never created any meaningful wealth are often amazed when they learn that many wealthy people are still motivated to continue working, often until they die. The thought process goes something like: ‘They have all the money they could possibly need, why are they still working?’ This displays a lack of understanding of both the role of work and the meaning of wealth for successful people. It also goes to the heart of one’s life goals.

Frederick Herzberg was a US psychologist who carried out a study on human motivation in the workplace.5 His main conclusion was that the most powerful motivator in our lives isn’t money; it’s the opportunity to learn, grow in responsibilities, contribute to others and be recognised for achievements. True happiness and fulfilment therefore are unlikely to be determined by your level of wealth or financial success, although life goals will, obviously, have a financial implication.

When I start working with a new client and I explore the motivations that drive them, it often becomes clear that work is actually a creative and defining part of their life. While building wealth may well have been an early motivation, more often than not the actual processes of leading people, innovating, building a business and making a difference are more important, particularly as the financial success becomes more tangible.

‘They don’t stop being an entrepreneur when they sell the company. Typically, an entrepreneur’s business is what defined them.’6

If being involved in business is something that makes you happy or enables you to pursue other meaningful life goals, then why not include that in your wealth plan, rather than aiming for a ‘retirement’ that may take away a lot of your purpose and meaning? It’s OK to still be working in your seventies or even eighties if it is in proportion to your other priorities and it makes you happy. As long as your life goals, which have a financial implication, are not dependent on you continuing to work, then why not work until you drop? Sometimes we need to look at wealth planning in a different way.

In Chapter 3 I’ll explain how you can use this knowledge with other key planning assumptions to help develop a robust framework for making key financial decisions, but first we’ve got to examine the role of financial personality and behaviour.

1 Frankl, V.E. (2004) Man’s Search for Meaning: The classic tribute to hope from the Holocaust, New Edition, Rider.

2 Bachrach, B. (© 2000–2011) Values-based Financial Planning: The art of creating an inspiring financial strategy, Aim High Publishing.

3 Kinder, G. (2000) The Seven Stages of Money Maturity: Understanding the spirit and value of money in your life, Dell Publishing Company.

4 Barclays Wealth Insights (2010) ‘How the wealthy are redefining their retirement’, Vol. 12, p. 4.

5 Herzberg, F., Mausner, B. and Bloch Snyderman, B. (1959) The Motivation to Work, Wiley.

6 Barclays Wealth Insights White Paper (2007) ‘UK landscape of wealth’, March, p. 8.