THE POWER OF A PLAN

‘Good fortune is what happens when opportunity meets with planning.’

Thomas Edison

I have already explained the importance of setting clear goals, developing financial planning policies and understanding your financial personality and risk profile. To develop a successful wealth plan, you need to put these goals into a wider context and review your overall financial position both as it is today and how it might be under various scenarios throughout the rest of your lifetime.

A good wealth plan should include the following elements:

- where you want to go – detailing your financial planning policies, goals, preferences, values and timescales

- where you are today – your current financial resources

- where you might end up – including analysis of your cashflow and family balance sheet, inheritance tax liabilities and insurance needs over the short, medium and long terms

- investment strategy – how you will allocate your current and any future resources across different asset classes

- other relevant planning issues such as tax, pension, gifting and charitable giving.

Where you want to go

In Chapter 1 we looked in detail at the importance of defining and quantifying clear goals, determining what is really important about money to you, and understanding your personal preferences. These should form the guiding principles on which your plan is based.

Where you are today

Knowing what you have and where documents can be located is a simple but important element of getting and staying well organised. How you choose to do this is up to you and it could just be a handwritten summary of your assets, liabilities, financial documents, insurance policies and trusts, or it could be a more formal spreadsheet. The important thing is to list what you’ve got and what you’ve done as this will help you to make more informed decisions. In addition, if you are incapacitated or die, it will avoid a drama for your family in trying to get to the bottom of your financial world.

Another common problem is not documenting or recording when gifts have been made. The type of gift, for example, whether to an individual or to a trust, whether it is exempt from inheritance tax or not, and when it was made, are all essential facts that need to be shared with your professional advisers, because this can have a dramatic impact on the eventual inheritance tax bill.

Where you might end up

Creating both a short-term and lifetime cashflow statement is, arguably, a very important measure for individuals when formulating a wealth plan. Although it will invariably turn out to be wrong in reality, it will provide a useful sanity check to the overall sustainability of your plan, from which you can draw some conclusions and assess progress. When you formulate your planning projections/analysis you will need to use some key assumptions. The following are the key ones that you (or your professional adviser) should include in your plan analysis.

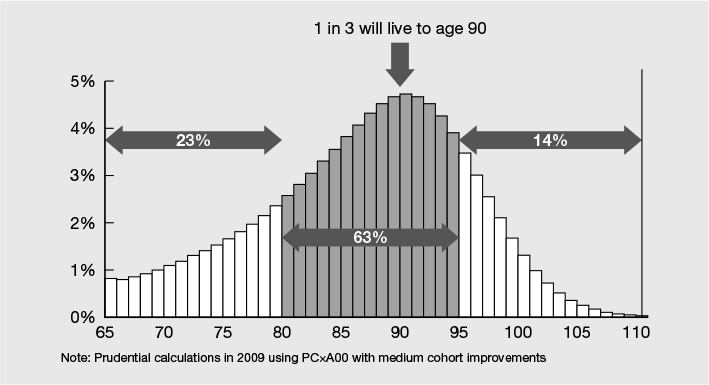

Life expectancy

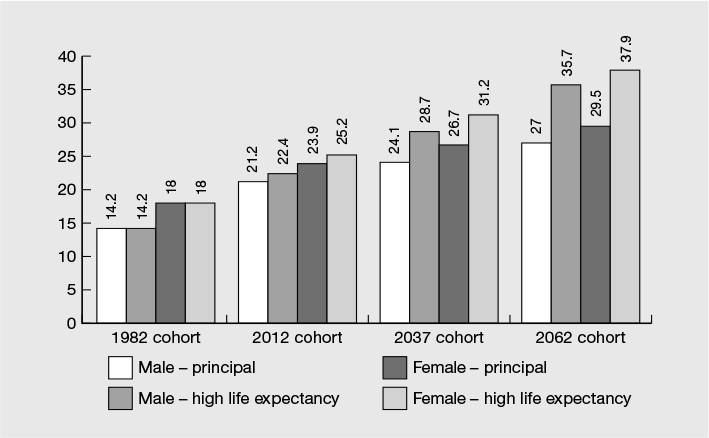

Clearly, your health will determine how long you expect to live, but with medical advances it may be longer than you think. The evidence suggests that most people underestimate their life expectancy by quite a big margin. As illustrated in Figure 3.1, a 65-year-old male has a one in three chance of living until age 90, and on average, a man and woman aged 65 can expect to live another 21.2 and 23.9 years respectively. Life expectancy at age 65 is projected to increase for men and women to 27 and 29.5 years respectively by 2062, but for the healthiest element of the population this is projected to be 35.7 for males and 37.9 for females, i.e. well in excess of 100. This is illustrated in Figure 3.2.

Figure 3.2 Projected life expectancy at age 65, 1982–2062

Source: Office for National Statistics (2013) ‘Historic and projected mortality data from the period and cohort life tables, 2012-based, UK’, December.

The numbers of centenarians in the UK has nearly quadrupled since 1981, from 2,600 to more than 12,000 in 2010, and nearly one in five people currently in the UK will live to see their 100th birthday.1 However, research from the University of Denmark suggests that a child born in Western Europe in 2007 has a one in three chance of living beyond 100.2 I recommend using age 99 as the default lifespan for financial planning purposes as this is well in excess of the average life expectancy at the time of writing, but you might wish to extend this to an even greater age, depending on your view on longevity.

Lifestyle expenditure

Ensure that the lifestyle expenditure assumption in your projection is reasonable and reflects what you do (or expect) to spend, not what you think you should be spending. It is better to overestimate your spending than underestimate it. The importance of being accurate about your current or desired expenditure will depend very much on the ratio of your regular spending shortfall (i.e. that not met by pension or other non-investment income) to your capital base and the investment strategy you adopt.

Although we do tend to spend less in later life as we become less active (various estimates put this at as much as 40% less), this might be countered by needing long-term care. I suggest that for planning purposes, therefore, you keep the projected expenditure amount constant in real terms throughout life, rather than aim for spurious precision by assuming a fall in living costs and allowing for specific long-term care costs. If your projected financial resources look a bit thin in later life, then you can drill into more specific expenditure projections.

Expenditure escalation

The Office for National Statistics publishes various measures of inflation that vary widely as a result of the different items included in the indices. The two that are of interest to individuals managing their wealth are the Retail Prices Index (RPI or RPIX; the latter excludes mortgage interest payments) and the Consumer Prices Index (CPI). The CPI measures inflation on internationally agreed standards throughout Europe and is now the basis on which allowances and most state benefits are escalated each year. The main difference between RPI and CPI is that RPI includes council tax and some other housing costs not included in CPI; it excludes certain financial services costs; and it is based on a smaller sample of the population. RPI also includes mortgage interest costs whereas CPI and RPIX don’t.

The CPI rate has tended to be lower than RPI/RPIX. The RPI/RPIX rate excludes items of expenditure incurred by the very poorest and very wealthiest members of society, on the basis that they are unrepresentative of wider society. In any case, it is highly likely that your ‘personal inflation rate’ will be higher than any of the official rates, particularly if you employ domestic help, pay childcare and/or school fees, own a second home or pay for comprehensive private health insurance/care. I suggest that you visit the ONS website (www.ons.gov.uk) to use its inflation rate calculator to work out your own inflation rate. Failing that I suggest you escalate your expenditure by CPI + 1%.

Convert pension funds to a simple level annuity

If you have substantial money purchase pension benefits, then it is unlikely that you will buy an annuity with all of them at the same time, if ever. For tax and investment reasons, it is more likely that you will take benefits from the pensions in stages and possibly some or all as income or capital withdrawn from the fund or possibly an investment-linked, rather than gilt-linked, annuity, as this is likely to provide maximum investment flexibility and the option to minimise tax.

However, for the purposes of your financial planning analysis, I recommend that you assume the lowest-risk, highest-tax position first, as this is the most prudent approach. Therefore, assume in your projection that any pension funds are used fully to purchase a guaranteed annuity at one point (between ages 60 and 70), inflation protected (you can always use a level annuity if the plan doesn’t work) and the maximum dependants’ income protection (this is usually 100% of your own pension, so it does not reduce on your death). If your plan works with this cautious assumption then you know that you have a fair amount of ‘wriggle room’ if things turn out differently. You can then consider how and when you take benefits to minimise risk and tax.

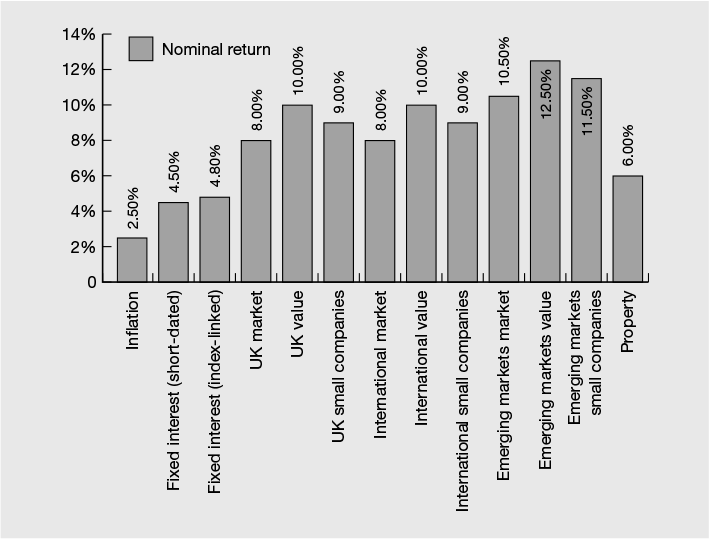

Use reasonable investment return assumptions

For many years the actuarial profession consistently underestimated the present-day value of the future liabilities of many final-salary pension schemes. This arose because the discount rate (i.e. the rate of expected future investment returns) used to calculate the present-day value of the scheme’s liabilities (the pensions due in the future) usually assumed a higher-risk investment strategy than many of the schemes were actually pursuing. So if you have half your capital in cash and half in bonds (fixed income), your expected return for long-term financial planning purposes needs to be lower than if you held, say, half in bonds and half in equities.

There has been much written about actual and expected returns from different asset classes but, as we will consider in Part 2, risk and return are related, and higher risks have a higher expected return. However, returns are rarely delivered in a straight line and there can be a range of outcomes (which is what makes them risky), as well as sometimes prolonged periods when actual returns are well below the long-term average. For this reason the forward-looking expected return in any wealth projection or analysis ideally needs to be below any historic returns.

In Figure 3.3 I’ve listed what I believe to be reasonable return assumptions for the main asset classes in nominal terms (i.e. inclusive of inflation) and before costs, which you’ll need to also take off the nominal return to arrive at the true projected return. Those costs will be influenced by the investment approach that you adopt, which we discuss in Chapter 10.

Figure 3.3 Asset class long-term annual investment return assumptions

Tax rates

If you (or your adviser) are using professional planning software, it will most probably calculate taxes reasonably accurately. However, it is not necessary to be spuriously precise about taxes as this is a moving target and tax rates will invariably rise and fall over your lifetime. It is perfectly reasonable to assume a simplified tax rate on investments of, say, 25% as reflective of the true rate of tax likely to be paid on income and gains, after allowing for allowances and other reliefs. Another key factor that will affect the amount of tax you pay will be where and how you locate your wealth – we’ll discuss this issue in Chapters 11, 14, 15 and 16.

All businesses have three key elements to their accounting: a cashflow statement, a profit and loss statement and a balance sheet. Individuals and families should be no different, although it is rare for them to apply the same structured approach to their personal wealth planning.

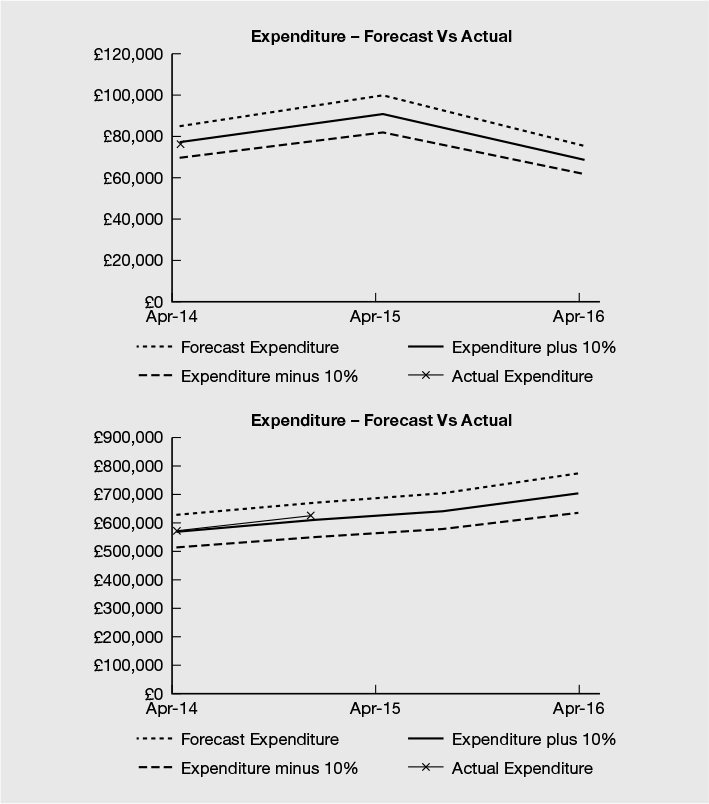

Short- and long-term cashflow projections

For the short-term cashflow projection, I suggest using a three-year time period, because experience suggests that this is the longest that most people can envisage with any degree of accuracy. The short-term cashflow can be extremely useful to identify any shortfall in income to meet lifestyle costs and/or anticipated capital expenditure. In either case, you can then ensure that you have an adequate (but not excessive) cash reserve, to meet such outflows, so that you are not a forced seller of risky assets such as equities and property-based assets. It’s a good idea to project the short-term cashflow with a 10% variance above and below the expected spending rate, as illustrated in Figure 3.4.

Although a lifetime net worth projection is almost certainly going to be wrong, as it is impossible to accurately predict all the factors that will impact on your wealth, it will give you a very useful idea of whether or not you have sufficient resources to meet your lifestyle and other long-term goals under a number of different, but plausible, scenarios. Professional wealth planners create cashflow projections as a starting point to help ascertain the client’s most likely financial position over various timeframes. Some online tools do the same thing, although they often adopt a simplified approach. Whether you use a planner with sophisticated financial planning software, a simple online planning tool or your own spreadsheet, the most important thing is to create a reasonable baseline financial scenario, from which you can draw some broad conclusions.

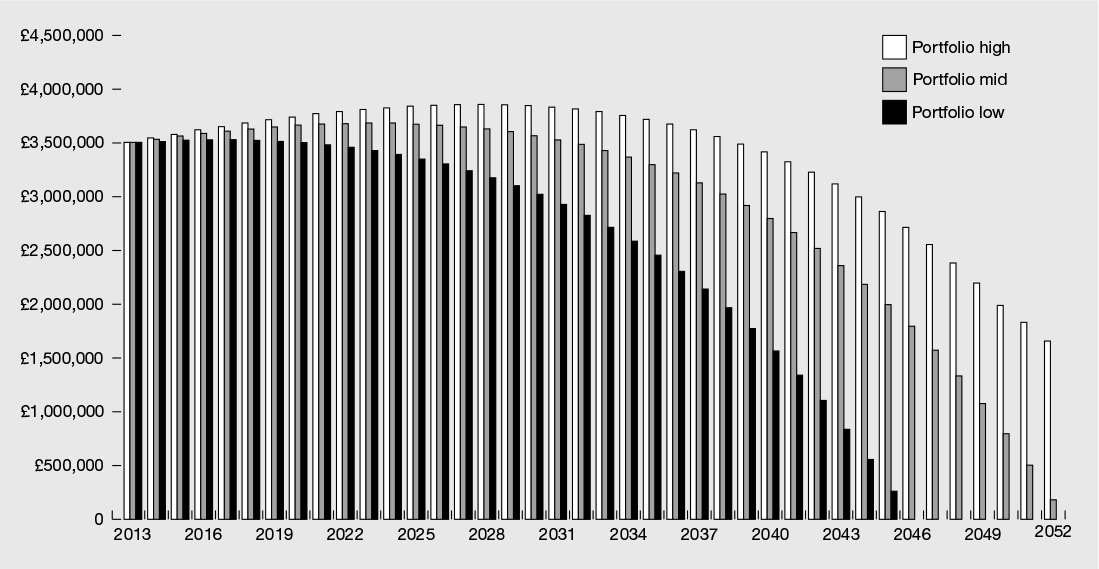

I counsel clients to assume three levels of lifestyle spending for lifetime financial planning projections: required, desired and aspired. In Figure 3.5 I’ve set out three different scenarios for the same individual, with differing levels of spending leading to different potential terminal values. The lower projection shows the capital being exhausted during lifetime, the higher projection leaving a substantial value on death and the mid-range scenario neatly showing a zero value on death. In the real world, investment returns, lifestyle spending, taxes and inflation all vary from year to year, so the outcomes can be substantially different to straight-line projections like these. They do, however, give a useful context as the basis of your planning, investment and tax-planning decisions. The planning projection scenarios can be varied based on different levels of spending, investment returns, taxes, downsizing property or gifting, depending on your circumstances and preferences. The key is to regularly review your lifetime projection in the light of reality, so that you can take any necessary action well before your financial security is adversely affected, not when it is too late.

Possibility and probability

In a world full of uncertainties it is easy to be seduced by those who profess to be able to predict how the future might turn out. We all want to avoid loss, pain and hardship, so anything that purports to help us do so is very appealing. The problem with any financial projection, particularly where it is over a long time period (20 years or more), is that it is almost certain to be wrong in reality. In the real world, investment returns, taxes and spending don’t happen in a straight, predictable line. That said, it is better to understand the possible outcomes before it becomes too late to do anything about it. In my experience, the level of annual lifestyle spending is usually one of the most important factors in determining whether a wealth plan is sustainable, although of course investment returns, inflation and taxes are also important factors.

There are various ways to ‘stress test’ a financial planning analysis, to determine the degree of probability of it being viable or not. All the approaches have shortcomings because they invariably suggest a degree of certainty about the future outcome of a financial plan, which is just not possible. However, the most widely used technique is called a Monte Carlo3 simulation. The investment return assumption used in a simple financial plan projection will be an average figure based on either historic returns achieved or (more usefully, as past performance is not a reliable guide to the future) that which the investor expects in the future. The ‘flaw of averages’ is that they mask the fact that there are usually big variations in the range of returns actually achieved, both above and below the average. Investors experience investment returns as they occur on a compound basis, i.e. they will vary from one year to the next.

In investment and financial planning, a Monte Carlo simulation program can be used to examine a random sample of historic or expected returns from an asset or portfolio of assets to determine a range of potential outcomes based on three key variables: the mean return (average from each period), standard deviation (a measure of risk) and correlation (how different assets perform when combined with each other). The software runs a year-by-year simulation of returns using a random sample of these three main variables to work out the probability of failure. Other factors such as inflation, expenditure and life expectancy are not changed, so no account is taken of the possibility that one or more of these might be affected by the investment return achieved. Most experts agree that it is necessary to carry out this simulation at least 100 times to be statistically robust, although some think that 300 iterations is the minimum.

The outcome of running the Monte Carlo simulations is a % probability of success, in the sense of how many of the simulations resulted in a surplus at the end of the investor’s time horizon. Thus, if 55 of the 100 simulations resulted in the portfolio not running out, the success rate would be described as 55%. I prefer to look at the results the other way round, in terms of the % probability of failure, and set a target failure rate of under, say, 25% to provide an adequate safety margin.

The probability of failure suggested by the simulation is not, in itself, sufficient to say that a planning and investment strategy is or is not appropriate; rather, it can provide an additional sanity check or early warning signal that the chance of failure might mean more frequent reviews of the plan are necessary to avoid failure or perhaps that more vigilance as to the level of annual spending is required. In any event, knowing a probability based on assumptions that are all highly likely to be incorrect is not generally considered a robust basis for decision making.

A Monte Carlo simulator (like any tool where the user’s understanding of it is flawed) in the wrong hands can be highly dangerous, but when used as one of a range of stress tests it can help avoid the false sense of security that a straight-line forecast might imply. Whether you work with a professional adviser or do your own planning, there is no substitute for regularly reviewing the sustainability of your financial planning and investment strategy.

The role of liquidity

Your wealth will almost certainly comprise short- and long-term liquid assets as well as used and unused illiquid assets. Liquid assets include cash deposits, most National Savings & Investments (NS&I) products, and quoted equities and bonds, both directly held and via daily priced investment funds. Used illiquid assets include your home, cars, boat or holiday home. Unused illiquid assets would include investment properties, business holdings, land/woodland, many structured investment products or alternative investments, such as hedge funds, that have long ‘lock-in’ periods.

Low-risk liquid investments such as cash or most NS&I products are easy to value as they comprise the capital and any accumulated interest. Such funds will also be accessible, depending on the terms of the account. They are also the best place to keep capital on which you expect to call within the next few years or just want to keep to hand for unforeseen emergencies. The only issue to watch is the financial security of the financial institution if you place more than £85,000 (£170,000 if you hold a joint account) in a UK-based account. Financial protection offshore is often less than that in the UK and, in any case, is only as good as the ability of the authorities in the jurisdiction to step up to the plate if an institution fails.

It is usually the case that most illiquid investments, like property, are valued less frequently than liquid ones and even then this is usually merely a matter of one person’s opinion rather than the price at which the asset actually changes hands. Securities listed on quoted investment exchanges, meanwhile, are valued in real time and reflect the best collective assessment that buyers and sellers place on the present value of the current and future dividends and profits growth of companies (in the case of equities) and interest yield relative to the inflation and general interest rate outlook (in the case of fixed interest bonds). Obviously the same applies to funds that invest in these securities, although they are often valued and priced daily rather than by the minute.

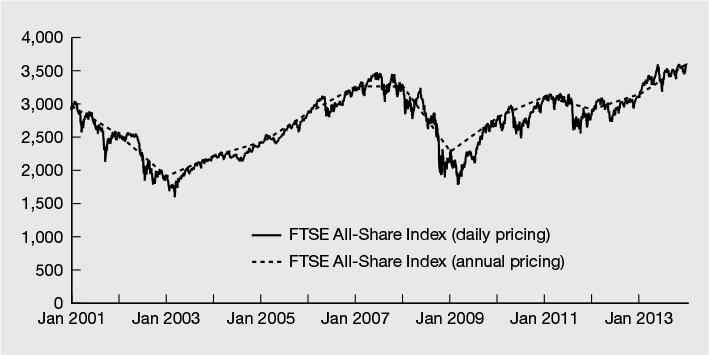

Figure 3.6 illustrates the impact of daily versus annual valuation points for UK equities using the same index. The daily version looks more volatile than the annual version but this is purely a function of the different price points.

Figure 3.6 Valuation frequencies for FTSE All-Share Index 2001–2013

Source: Data from Bloomsbury Wealth Management, FTSE.

While it is true that some unused illiquid investments can produce very high returns, this usually comes with additional and sometimes unanticipated risks (always remember that risk and return are related). In addition, some illiquid investments such as property or unquoted trading businesses require more oversight and input from the investor and may have ongoing maintenance costs, which must be paid from any income arising from the investment or from your other (liquid) capital or income.

Illiquid investments are not necessarily a bad thing as long as you have access to sufficient cash inflows and reserves to meet current needs. The famous Yale Endowment fund in the United States has achieved long-term returns well above a traditional liquid investment portfolio over the past 25 years, precisely because it invests much of its capital in illiquid holdings. Over the longer term the fund intends to invest half of its portfolio to the illiquid asset classes of private equity, real estate and natural resources.4 We’ll discuss investment fundamentals and options in Chapters 5–9.

Don’t forget that your main home may well represent a large part of your wealth and as such may mean that you already have a high exposure to property. Just because you can see and touch something doesn’t make it a sure bet. Investment property can form an asset base from which to build your wealth plan, but it is not a one-way street and to maximise your returns you either have to be prepared to spend time managing the asset or outsource this task to someone else (which has a further cost implication). Either way my advice is that you shouldn’t kid yourself that property is the answer to your investment problems, nor that it provides superior long-term returns at lower risk than a liquid, highly diversified investment portfolio. Property is affected by the reality of the economic conditions prevailing. If people and businesses cannot afford the rent you want to charge or the purchase price then these will simply adjust to reflect the reality of supply and demand.

The perceived lower risk of property compared with equities is just that – a perception. Where property is represented by an index fund that is valued and traded daily on an investment exchange, it exhibits similar (but not exactly the same) fluctuations in price and sentiment as quoted equities. Listed global commercial property (known as securitised) has a correlation of about 0.50 against UK equities and 0.60 against global equities.5

Investment in an unquoted business (which can include the business of developing and/or renting property), whether your own or someone else’s, usually offers the highest reward but also comes with a different, and sometimes much higher, set of risks. If you have owned your own business and have now sold it for cash, then you need to think very carefully about whether reinvesting your money, or at least the vast bulk of it, into another unquoted business is really in line with your future lifestyle and other life goals. If freeing up time is important to you and/or reducing the risk of losing money matters, then perhaps it would be better to invest your non-cash reserve capital into a fully diversified, liquid investment portfolio. However, there are always exceptions to the rule and the case study of Nigel and Mary (see below) is an example.

Some people who have been successful in business are interested in mentoring young and growing businesses. Sometimes this also involves investing some cash in the business, referred to as ‘angel investing’, and it can be extremely rewarding, both personally and financially. Allocating a small proportion of your capital to angel investing might make sense if you have the interest and necessary time to help nurture new and growing businesses. However, it is rarely good advice to put all your hard-earned capital into such a concentrated risk, particularly if preserving what you have is your key concern and you would not be able to recover from any loss. My advice is to view such investments as ‘fun’, like indulging a hobby, and to disregard them from your overall financial resources unless they become cash again.

Case study

The caravan couple – when business investment is best

Some years ago I met a couple, let’s call them Nigel and Mary (not their real names), who had sold a successful caravan park business for several million pounds after 20 years’ hard work. During the wealth-planning process it became apparent that neither of them wanted to stop being involved in a business (they were in their early sixties). They also felt that reinvesting the bulk of their liquid wealth into another caravan park business might be the best solution for their wealth plan, provided that they could delegate the day-to-day management of the business to staff. The couple looked at a number of suitable businesses and, drawing on their considerable experience of owning and running such a business, they decided that those on offer were not good investments.

After a few months a more suitable business came on the market and after hard negotiating the couple bought it. The business would comfortably generate an income of £100,000 per annum for each of them, which more than funded their lifestyle after tax. In addition, Nigel and Mary could employ their daughter on a part-time basis for £40,000 per annum, which, as well as being taxed at no more than 20%, allowed her to indulge her passion for regular travelling. The business was asset-backed in the form of the land on which it was sited and it would also qualify for exemption from inheritance tax after two years and capital gains tax at 10%, should they ever decide to sell it in later life.

This still left them with about £500,000 of surplus cash, which we decided should be spread between instant and notice deposit accounts and NS&I products so as to provide them with an adequate cash reserve while they settled into the new business. Nigel and Mary are very happy with their ‘investment’ and so is their daughter.

If you have attained financial independence or are almost there and have life plans that do not include spending your precious time overseeing business investments, properties or picking the next ‘hot’ investment, and you are looking for ‘elegant simplicity’, the best investment solution is likely to be to invest your long-term capital into a well-diversified, fully liquid investment portfolio allocated in line with your risk profile.

‘We ignore the real diamonds of simplicity, seeking instead the illusory rhinestones of complexity.’

Jack Bogle6

Identifying and understanding financial planning risks

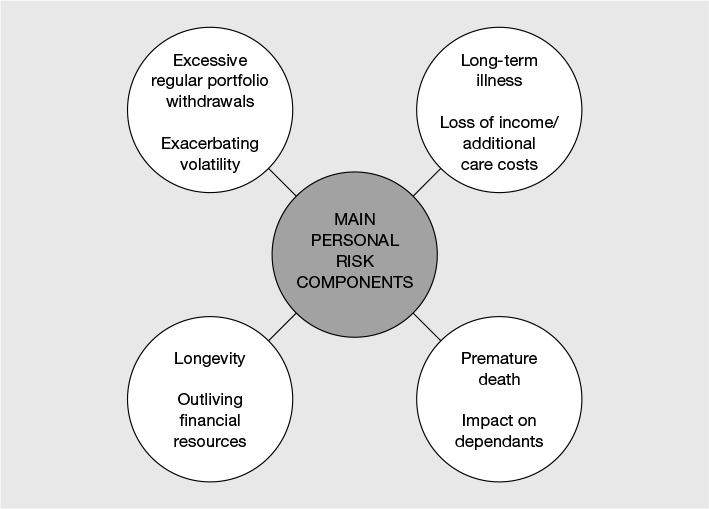

Even if you are clear on your money values, goals, personal preferences and have a robust wealth-planning analysis, before you think about how you might deploy your wealth, you need to also be clear on a number of risks. Risk means different things to different people, but as a financial planner I see it as the failure to achieve those life goals that have financial implications, however you define and quantify them. From a financial planning perspective, risks can be grouped into three areas: personal, behavioural and deep, as illustrated in Figure 3.7.

Personal risks

Examples of personal risks include long-term illness and the impact this might have on your lifestyle and human capital (earning ability/potential) – dying too soon or living too long relative to your financial commitments and resources. Illness and death can usually be dealt with by buying insurance (although not always for those with existing medical problems). Living too long, otherwise known as longevity risk, can be dealt with through a combination of insurance (in the form of annuities), accumulating sufficient wealth to sustain lifestyle spending and investing in a range of asset classes.

Another form of personal risk is where an investor overdraws from their portfolio to meet spending, thereby greatly increasing the possibility of plan failure. We’ll look at the impact of regular portfolio withdrawals, and how this can affect plan viability, in Chapter 12.

Behavioural risks

As we explored in Chapter 2, investors’ wealth-destroying behaviour includes being either over-optimistic or over-pessimistic in the light of news and investment sentiment. This often leads investors to sell out when investment markets have fallen sharply (in March 2009 developed investment markets were almost 50% below their previous peak) and miss the inevitable strong rebound, or pile into the latest fad investment.

Deep risks

Financial theorist William Bernstein suggests that investors think of risk as either ‘shallow’ or ‘deep’, with shallow risks relating to personal and behavioural factors.7 Deep risk is the permanent loss of capital – defined as a real (that is, after inflation) negative return over a 30-year period. By analysing historic data to determine the causes for a permanent loss of capital, Bernstein has identified four main sources of deep risk: inflation, deflation, confiscation and devastation.

Inflation – the rate of increase in the price of goods and services each year.

Deflation – the rate of decrease in the price of goods and services each year.

Confiscation – when property or other assets are either seized by the state or subject to penal tax charges.

Devastation – mainly relates to environmental factors, such as earthquake, hurricane, fire, which leads to the permanent loss of assets.

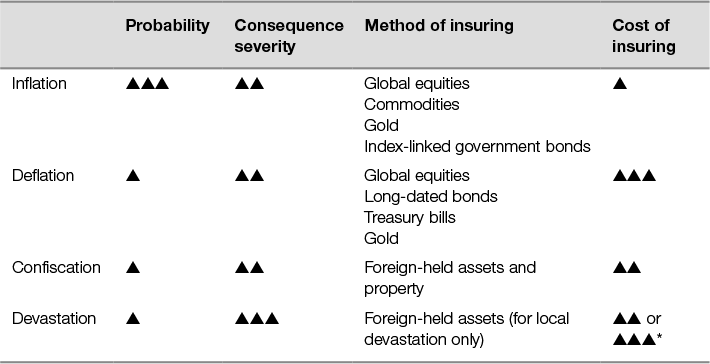

Because these economic and political factors may permanently destroy part or all of your wealth, Bernstein suggests using a three-point scale for analysing and defending against these risks using four factors: probability, consequence severity, and both method and cost of insuring, as set out in Table 3.1.

Table 3.1 Deep risks

*Depends on country of residence.

Source: Data from Bernstein, W. (2013) Deep Risk: How history informs portfolio design, Efficient Frontier Publications.

Bernstein concludes the following:

- Shallow risk is the main risk for investors in later life with little or no earned income.

- Shallow risk and inflation are the main risks for investors who have enough money to live on for the rest of their lives and inflation-linked government securities are most likely to be the favoured route. Although long bonds offer the best protection in a deflation environment, Bernstein thinks the probability of deflation is low and in any event, capital doesn’t fall in real value and taxes would be lower.

- Shallow risk is a good thing for younger people who are still accumulating wealth, as long as they can stay the course and they or their adviser rebalances the portfolio when equities are over or under the target allocation. Bernstein suggests they invest in a geographically diversified equity portfolio, with 30–40% in international equities, possibly with an overweighting to precious metals and mining stocks as well as energy, which has also provided some protection against inflation, historically. Some fixed income is still needed, however, if only to allow for rebalancing.

- Investors who have a significant portfolio but haven’t completely met their financial goals have a trickier decision to make. A more balanced portfolio, with high-quality bonds, such as inflation-linked gilts, and the equity allocation set out above is favoured, as long as the portfolio is rebalanced when shallow risk occurs.

- Bernstein concedes that there’s not much most people can do to protect against confiscation and devastation risks ‘beyond [having] an interstellar spacecraft’. He suggests owning a few gold coins and giving a bit more consideration to foreign real estate. ‘If the client was already considering buying a flat in London,’ he says, ‘the potential for confiscation and devastation could be additional reasons to pull the trigger.’*

*Clearly UK-based investors would need to buy property outside the UK.

Investment strategy

An integral element of your wealth plan will be the design and implementation of your personalised investment strategy in the form of an investment policy statement (IPS). This sets out how you will allocate and maintain your long-term, liquid investment portfolio. This document should detail the following information:

- your financial goals for the investment portfolio

- the rate of return required, as identified in the lifetime cashflow analysis

- the monetary amount that you intend to withdraw from (or add to) the portfolio each year

- the asset allocation strategy and specific allocation to different asset classes

- the investment philosophy

- the rebalancing policy, including when and how this will be done

- a statement of the action that you will take in response to adverse life or investment events by reference to your financial planning policy statements

- your tax management approach or policy such as it relates to the portfolio.

The IPS should act as the key reference point for your investment strategy and provide you with the discipline to stick to the plan, particularly when things don’t turn out as you expected. If you decide to delegate some or all of the management of your wealth to a professional investment manager, then the IPS can also be used as the basis of the manager’s brief for managing the portfolio.

Writing down your financial position and key goals, getting financially organised, carrying out a viability analysis of your resources and articulating and documenting your investment approach will force you to think about the way that you manage your wealth. It will also serve as a useful reference point from which you will be able to measure your progress and also stay disciplined in the face of adversity.

The future is always uncertain

Working out what is financially possible, the probability of different financial outcomes, how best to structure your wealth and how you should respond and adapt to the inevitable changes that will arise in the future are key to maximising the likelihood of financial success. For this reason you may well benefit from the advice, assistance and counsel provided by a financial planning professional. In the next chapter we’ll look at the role of guidance and advice and how to choose the right service and/or adviser.

1 Age UK (2014) ‘Later life in the United Kingdom’ February, pp. 3, 6.

2 Christensen, K., Doblhammer, G., Rau, R. and Vaupel, J.W. (2009) ‘Ageing populations: the challenges ahead’, The Lancet, 374 (9696): 1196–1208.

3 An excellent in depth explanation of Monte Carlo analysis can be found in The Kitces Report (January 2012), which you can download from www.wealthpartner.co.uk/downloads/Kitces_Report_January_2012.pdf

4 The Yale Endowment 2013 investment report.

5 Philips, C.B. (2007) ‘Commercial equity real estate: A framework for analysis’, Vanguard Investment Counseling & Research, www.vanguard.com/pdf/s553.pdf?2210022068

6 Bogle, J. (2009) Enough!, Wiley, p. 23. John Bogle is founder and former CEO of the Vanguard Mutual Fund Group.

7 Bernstein, W. (2013) Deep Risk: How history informs portfolio design, Efficient Frontier Publications.