PHILANTHROPY

‘We make a living by what we get, but we make a life by what we give.’

Winston Churchill

In Chapter 1 we looked at Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and the fact that, as our own and our immediate family’s needs are met, it is natural to seek a higher level of fulfilment, meaning and purpose: the process of self-actualisation. Giving time or money to causes from which neither you nor your family can directly benefit is clearly an altruistic and selfless act and may help you to achieve that feeling of greater meaning and purpose in your life.

Giving time

Helping people or causes doesn’t have to mean giving away your wealth. Giving your time can be equally valuable and, in many cases, more fulfilling. There are numerous organisations throughout the UK that offer ways for people to volunteer their time and expertise across a diverse range of roles, examples of which are:

- magistrate

- special police constable

- school governor

- working with prisoners or detainees

- hospital visitor

- advocate for vulnerable individuals

- visiting elderly people

- education support

- National Trust, RSPCA, RSPB, etc.

Sometimes, particularly in poorer countries, sharing your skills and knowledge can be extremely valuable. Voluntary Service Overseas (VSO) is one of the world’s largest independent international development organisations, which works through volunteers to fight poverty in developing countries. ‘VSO’s high-impact approach involves bringing people together to share skills, build capabilities, promote international understanding and action, and change lives to make the world a fairer place for all.’1 There is high demand for teachers, engineers and health workers, as the provision of education, infrastructure and health services is sparse in many developing countries.

An acquaintance of mine, who is very successful and wealthy, derives great meaning and pleasure from supporting the building and upkeep of schools in Africa. As well as making cash donations, he and a few friends go to Africa to provide hands-on help with the building and painting. This has the added benefit of enabling him to see the real difference that he is making on the ground by meeting the staff and pupils of the schools he has helped, thus motivating him to continue his support.

Giving money

While philanthropy is something that is well understood and practised in the United States, it less so among wealthy people in the UK. A study found that only 18% of wealthy individuals in the UK said charitable giving was one of their top three spending priorities, compared with 41% of their US counterparts.2

This reticence to give certainly doesn’t seem to be related to wealth. Over the years I’ve met modestly affluent people who give 10% of their earnings to charity, even though they have not achieved financial independence themselves. In other cases I’ve met multi-millionaires with far more wealth than they or their family could ever spend, but they make only modest charitable gifts. Research shows that the poorest 10% of donors give 3.6% of their total spending to charity, whereas the richest 10% give only 1.1%.3

A common barrier to higher giving is that wealthy people often feel they can’t afford to give much to charity until they feel financially more stable. A 2010 study found that 71% of wealthy people give only when they feel financially secure.4 It is natural for people to feel less secure when the economy has suffered a downturn, such as the recent global credit crisis. But this is unlikely to be the only or even the main reason for reticence to gift more meaningful amounts to charity.

It is probable that some people see giving to charity as complicated, or worry that it will unleash a rush of begging letters. Others see charities as inefficient and think that very little of their gift will be used to make a real difference, once administration charges have taken their share. In my experience, the biggest reason that charitable giving isn’t a bigger priority among affluent and wealthy individuals is because they haven’t given it any real thought or consideration. While they might respond to disaster requests or TV appeals, it is the exception, not the norm, for people to seriously consider how charity fits into their wealth planning.

Let’s go back to that question in Chapter 1: ‘What’s important about money to you?’ If you can identify a cause with which you really connect and develop a passion for, then you are much more likely to be motivated to make more meaningful gifts in your lifetime and/or through your will. This is where a good wealth adviser can add value, by helping you to work out what causes are important to you and selecting charities – possibly by engaging a charitable giving specialist – and determining how to give easily and tax-efficiently and, more importantly, to monitor the impact of your giving.

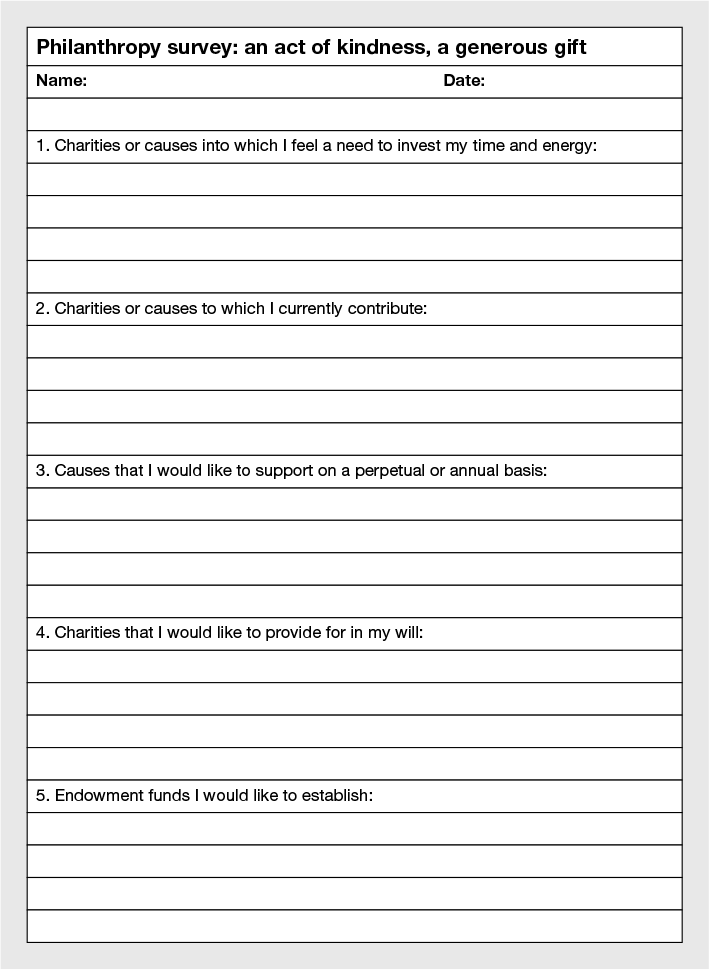

Financial giving can be done in your lifetime on a planned or ad hoc basis and/or left for the executors of your will to deal with after your death. Clearly, if you give in your lifetime, you can derive some personal satisfaction from the outcome. I use a philanthropy questionnaire with clients to help them identify what, if any, philanthropic aims they have and this is reproduced in Figure 24.1 should you wish to use it.

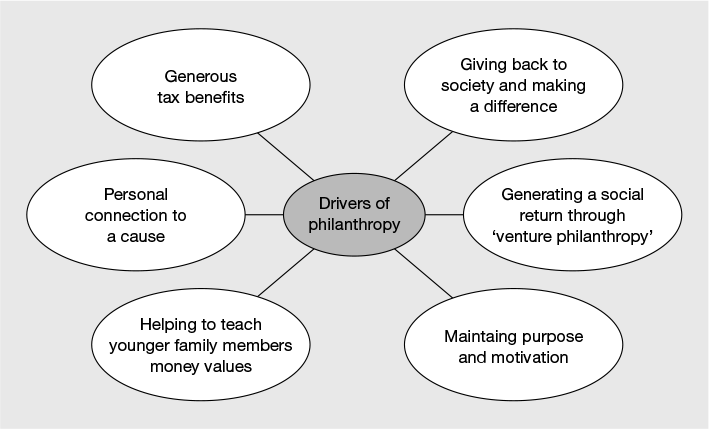

Reasons for giving

There are six key reasons why you might want to make charitable giving a serious part of your wealth plan, as set out in Figure 24.2 and discussed further below.

Figure 24.1 Philanthropy survey

Giving back to society and making a difference

Bill and Melinda Gates and Warren Buffett have given billions of dollars to the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which is the largest transparent, managed independent foundation in the world, with an endowment of $36.3 billion. The Foundation aims to advance education and technology use in the United States and to eradicate malaria, polio, HIV/Aids and poverty in the developing world, and has distributed $25.36 billion to date.5 Gates and Buffett announced that more than 50 prominent businesspeople have made a public pledge to make more substantial charitable donations. Warren Buffett said:

‘Were we to use more than 1% of my claim checks (Berkshire Hathaway stock certificates) on ourselves, neither our happiness nor our well-being would be enhanced. In contrast, that remaining 99% can have a huge effect on the health and welfare of others.’6

While you may not be able to make donations on the same scale as the Gateses and Buffett, you could almost certainly make donations that would have a significant impact and make a big difference. The problem with making small donations to lots of charities without any real strategy is that it dilutes the impact of the donations and erodes the satisfaction derived from giving. The power of philanthropy comes from the focus and drive of the philanthropist. It also allows affluent and wealthy families to stay connected with the wider world and each other and to give something back, making a difference that will last beyond their lifetimes. The purpose of philanthropy is, therefore, to make an impact, change things about which you are not happy and, to a large extent, pass on these positive values to your wider family – more of which later.

Maintaining purpose and motivation

Many successful people maintain a strong sense of purpose and motivation by generating wealth to fund charitable causes about which they care deeply. The singer Elton John is well known for the fundraising that he does for his AIDS charity. The singer and actor Roger Daltrey has been a keen supporter of the Teenage Cancer Trust, which he helped to establish in 2000, and he speaks with passion and conviction about how this helps him to stay positive and enthusiastic about his life purpose, as well as keeping in touch with those much less fortunate than himself.

Successful businesspeople are increasingly making sizeable gifts to their own charitable foundations or established charities, at the expense of leaving a larger legacy to their family and friends. Sometimes this provides a business owner with the motivation to continue in business and defer, indefinitely, any notion of ‘retiring’. Tom Hunter, the Scottish entrepreneur, is a good example of a self-made person who keeps working to fulfil his higher calling in life. After selling his business, Sports Division, to JJB Sports for £290 million in July 1998, Sir Tom moved to Monaco for tax reasons. At the same time, he established a charitable foundation – The Hunter Foundation – with £10 million, initially as a tax-mitigation tool.

Hunter explained that he had realised making money was ‘only half the equation’ and announced, after setting aside enough money to keep him and his family comfortable throughout their lifetimes, he would return to live in the UK and continue to invest in and nurture new businesses via his private equity company, West Coast Capital. He intends to channel gains and profits arising from his private equity investment into charitable causes in what he calls ‘venture philanthropy’. In 2011, the foundation had invested £50 million.7 Hunter said in an interview:

There is more great wealth in fewer hands than ever before in history. My own personal belief is that with great wealth comes great responsibility … all the material goals have all been settled some time ago, so now the philanthropy is the real motivator to continue to make money. The aim is to redouble our efforts in wealth creation in order that we can, over time, invest £1 billion in venture philanthropy through our foundation.8

Helping to teach younger family members money values

Teaching young people the value of money and a sense of responsibility in terms of how to manage wealth sensibly can often be made easier by engaging family members in the process of giving. While this could be as elaborate as a family ‘board’ to guide giving by a dedicated family charitable trust, it can also be a simple matter of making sure that giving is a regular part of family dialogue.

In my family, for example, once a year, each of us has to choose one large and one small charity to which we would like to make a charitable donation and explain why. In the case of my daughters, they each have to donate £1 of their own savings for every £10 given by my wife and I. This achieves a number of objectives:

- My daughters know that planned charitable giving is a key priority for my wife and I.

- By each supporting a large and a small charity, we strike a balance between those organisations that may have a high impact in terms of results but are not as well funded as the more visible and established charities that are well funded, proven and have economies of scale.

- Making our own donation subject to our daughters also making their own contributions causes them to make a small sacrifice of their own money and to appreciate what they have compared with others.

- The act of actively choosing our charities gives each of us a sense of ownership and engagement in the giving process.

- Talking and thinking about charitable giving causes us as a family to think more about others and less about ourselves, which also helps to give us all a greater sense of meaning and purpose in life.

- It gives us all more motivation to do our best in our lives and share the financial fruits of our efforts.

Just as it’s never the ‘right’ time to start a family, it’s never the right time to start charitable giving. If you wait until you feel wealthy enough, the opportunity to make a real difference to others is likely to have been missed.

Personal connection to a cause

The reason that cancer and heart disease charities are well funded is because almost everyone knows someone who has been affected by those conditions. I have a particular interest in education and parenting, as they are both issues that I feel go to the heart of many of society’s problems and my own experiences of both were less than ideal. The more you connect with and feel passionate about a cause or issue, the more likely it is that you will be motivated to support it. In addition, you will probably derive more pleasure and satisfaction from charitable giving to that cause, particularly if you are clear what your gift is being used for and can see tangible results.

I suggest that you widen your net a bit more than the usual charities and think carefully about whether there are less mainstream, but equally worthy, causes with which you connect and that are important to you personally, as a gift to one or more of these might have a much higher impact and social return. I have known clients who feel strongly about the value of a good education and they have provided funds for free or subsidised education for disadvantaged pupils at some of the best independent schools. Although not a charitable gift, I’ve also known people agree to fund some or all of the educational needs of their relatives’ or friends’ children, sometimes requiring a matching contribution, pound for pound, to ensure a sense of ownership and responsibility on the part of the child’s parent.

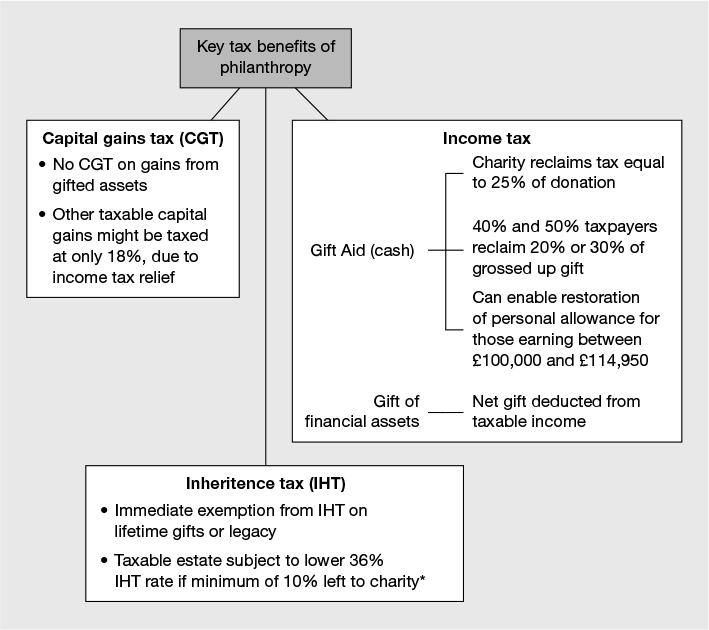

Generous tax benefits

The government is keen to support charitable giving and wants to encourage a more giving society. One of the ways that giving is encouraged is by offering a number of very generous tax benefits. These include income tax relief, freedom from capital gains tax on assets gifted and exemption from inheritance tax on lifetime gifts or those made on death, as summarised in Figure 24.3.

Figure 24.3 UK tax benefits for charitable gifts made by individuals

Gift Aid

For cash gifts it is better for all concerned to make a gift that falls within the Gift Aid scheme. Gift Aid allows a charity to reclaim basic-rate tax on donations from UK taxpayers and enables higher-rate and additional-rate taxpayers to claim 20% or 30% tax relief, respectively, on the amount of the gift grossed up for basic-rate tax. If the amount of UK tax (income tax and/or capital gains) paid by the donor is less than the amount of basic-rate tax that the charity can reclaim, the shortfall has to be repaid by the donor to HMRC, although in practice this is rarely done.

Example

Claudia is a higher-rate taxpayer and gives £8,000 to a recognised charity. Under the Gift Aid scheme, this will be treated as a gift of £10,000 (£8,000 grossed up by 25%), from which the basic-rate tax of £2,000 has been deducted at source. The charity can reclaim the basic-rate tax of £2,000 directly from HMRC, so it will receive a total of £10,000.

As Claudia is a higher-rate taxpayer with taxable income of £45,000, she may claim higher-rate tax relief on the gift. This is calculated as follows:

| Grossed gift | £10,000 |

| Tax relief at 40% | £4,000 |

| Less: tax deducted when gift made | (£2,000) |

| Reduction in Claudia’s tax liability | £2,000 |

If Claudia were an additional (45%) rate taxpayer, the corresponding reduction in liability would be £2,500 (i.e. 25% of £10,000).

Other income tax benefits

The reduction in higher/additional-rate tax is given by an increase in the basic-rate income tax band equal to the grossed-up gift. In the example, Claudia’s basic-rate band would be increased from circa £32,000 to £42,000 for the tax year 2014/15. This means that any dividend income otherwise taxable at 32.5% (less the 10% credit) could fall within the extended basic-rate band with no extra tax payable.

If Claudia had taxable income of £20,000 and, as such, had lost her personal income tax allowance,9 then a gift of £16,000 would gross up to £20,000 and extend her basic-rate income tax band by the same amount. This would bring Claudia’s taxable income down to £100,000 and enable her to retain her personal income tax allowance, thus providing effective personal tax relief of 50% on the net cash donation and 75% including the tax reclaimed directly by the charity.10

It is also possible to make a gift and carry this back to the previous tax year, subject to you having paid sufficient income tax in that tax year to meet the tax claim by the charity. The deadline for carrying back a gift is on or before the time you make the donation but no later than 31 October (if you file a paper tax return) or 31 January (if you file an online tax return) in the year that the gift is made.

Gift Aid and chargeable events on insurance bonds

It is important to note that the basic-rate tax band is not extended for the purpose of computing relief on top-sliced gains under a life assurance policy.11 For example, if Claudia had taxable income of £31,000 after allowances for the tax year 2014/15 and the top-sliced gain under a single-premium bond was, say, £2,000, then higher-rate tax would usually be calculated on £1,000 (i.e. £32,000 – £31,000).

Were Claudia to make a gross Gift Aid payment of £1,000, then, although the basic-rate threshold would be increased to £32,000, for top-slicing relief it would be held at £31,000, so the higher-rate tax would still be based on a chargeable gain slice of £1,000.

Capital gains tax and Gift Aid

Taxable capital gains (after deducting losses and/or the annual capital gains tax exemption) are taxed at 28% unless the taxable gain falls within your unused basic-rate income tax band of, currently, circa £32,000, when it will be taxable at 18% to the extent that it falls within the basic-rate band.

For example, Stephen has total taxable income after personal allowance of £32,000 and taxable capital gains of £25,000.

| Gains that fall within basic-rate tax band | Nil |

| Gains that exceed the basic-rate tax band | £25,000 |

All of the gain will be taxed at 28%, resulting in a liability of £7,000. If, however, Stephen made a charitable donation under Gift Aid of £20,000, his basic-rate income tax band would be increased by the amount of the grossed-up gift (£25,000), to be £57,000. After deducting his taxable income of £32,000, this means that he has £25,000 of unused basic-rate income tax band and, as such, the entire taxable capital gain will be taxed at 18% – i.e. £4,500 rather than £7,000 had he not made the contribution. See Chapters 14 and 16 for more on capital gains tax planning.

Non-cash gifts to charities

Although the Gift Aid scheme does not extend to non-cash gifts, it is also possible to obtain tax relief at your marginal rate(s) of income tax, as well as exemption from capital gains and inheritance tax, by donating ‘qualifying assets’ to a registered charity or foundation, including one created by yourself.

Such ‘qualifying assets’ include:

- quoted shares (on a recognised exchange)

- units or shares in a unit trust or OEIC

- shares or units in an offshore fund

- a freehold interest in land in the UK or a leasehold interest in such land for a term of years absolute.

Relief is given by way of deduction against income otherwise subject to tax. The amount that can be deducted is broadly the market value of the asset gifted plus the incidental costs of disposal, e.g. commission, costs of transfer. So, if a donor with a taxable income of, say, £125,000 gave qualifying shares worth £50,000 to a charity, the donor’s taxable income would be reduced to £75,000, resulting in an income tax saving of £20,000 (40% of £50,000).

In addition:

- there would be no capital gains tax to pay on the gift, even if the shares had appreciated in value since their acquisition, and

- there would be no inheritance tax on the gift.

It is also possible to sell an asset to a charity at below its market value and, in this situation, the proceeds are deducted from the gift value for the purposes of determining exemption from capital gains and reducing taxable income.

Charitable legacy IHT reduction

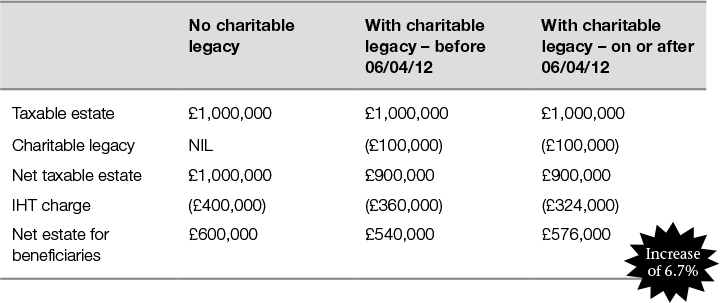

Where at least 10% of your taxable estate is left to a registered charity, the remainder of your taxable estate will be taxed at 36% rather than the standard 40% IHT rate. If you were not going to leave money to charity on your death, this rule will not motivate you to do so, but it’s nice to know that it is costing the estate only 60% of the gross gift, as shown in Table 24.1.

Table 24.1 Effects on net estate of charitable legacy rule

Ways to give

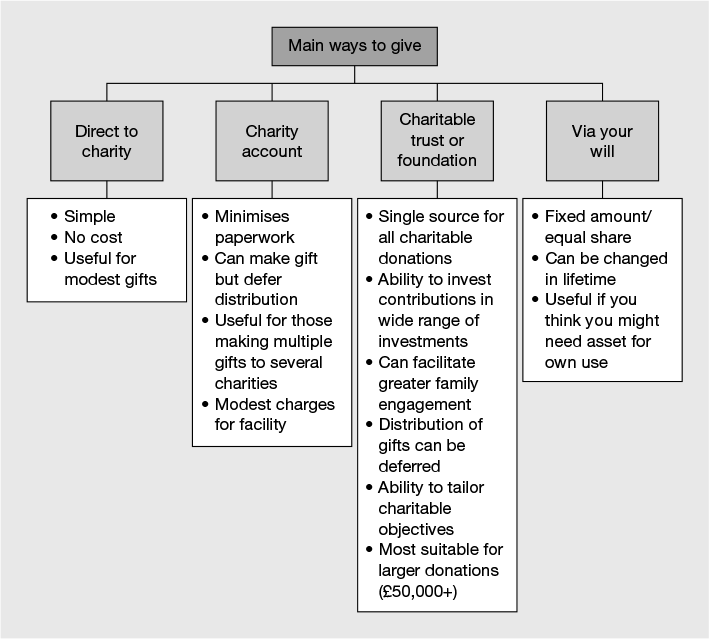

There are four main ways to give to charities, as set out in Figure 24.4. The receiving entity must, however, have a charity reference number issued by HMRC.

Direct to charity

This means that you gift cash or a financial asset directly to your chosen charity. This is simple and is best if your overall level of giving is modest, ad hoc and you are good at keeping on top of paperwork for when you come to complete your tax return.

Figure 24.4 Main ways to give

Charity account

If you want simplicity, particularly if you make gifts to lots of charities each year, and/or you want to obtain the tax benefits now but defer a decision on which charities to support, a charity account can be very useful. These accounts are similar to a normal bank current account, in that you pay cash donations into the account, which usually earns a modest amount of interest. Withdrawals are permitted only in order to make donations to your chosen registered charities and these can be done electronically or by issuing cheques. Charity accounts are offered by a number of organisations, including the Charities Aid Foundation (CAF) and Charities Trust, although they do make a small charge on each contribution and a small annual charge.

Charitable trust or foundation

This is a personalised type of trust that attracts charitable status and provides a high degree of flexibility over how funds can be deployed, although neither you nor your family may benefit from the trust personally. Like a charity account, a charitable trust allows you to make substantial donations but defer deciding which charities are to benefit. Alternatively, you could build up capital, of which you could delegate the management to a professional investment manager, which will fund ongoing charitable giving long after you’ve ceased to make contributions. In addition, there is greater flexibility to invest in businesses, whether social or normal commercial enterprises, that you think will have a high social impact and/or generate significant profits or capital gains that can be distributed to charities.

The Charity Commission,12 however, is getting hot on making sure that charities do distribute funds rather than leave them to stockpile. So, you could have problems if you set up a charitable trust and then contribute funds to it for a period of years without ever paying anything out. The best approach is probably to ensure that you start to make distributions within a few years of setting up the trust and to keep making distributions, even if these are less than the ongoing contributions and any investment growth.

Because the costs of setting up and managing a charitable trust are higher than for a charity account, they are most suited to those making a more substantial gift – usually £50,000 or more. In practice, however, contributions to this type of structure are usually in excess of £250,000. Although a charitable trust or foundation is usually set up by a lawyer, organisations such as CAF can provide you with your own charitable trust that is pre-approved with HMRC and for which they handle all ongoing administration and compliance for a competitive price. In addition, they have a range of external investment options at preferential rates. However, if you have specific needs and objectives, or you like the idea of having a bespoke charitable trust, go ahead and have your legal adviser create the entity for you.

Via your will

Leaving a legacy to one or more charities via your will is easy. It can be changed at any time while you are alive and avoids you having to give away cash or assets that you might need to call on for your personal use in your lifetime. You could stipulate a fixed amount or specific asset or give all or part of your residue estate. There can be issues with each, particularly where confusion can arise if you have a list of gifts in your will, some of which are tax-free and some of which are not. You need to make clear your intentions – i.e. whether they each receive the same amount net or the charity receives more because it’s tax-free.

In the next and final chapter we’ll go back to where we started in Chapter 1, when I asked: ‘What’s important about money to you?’ I’ll share with you a few final thoughts on living a life with a purpose to help with the motivation needed to ensure that your wealth helps to achieve all that is important to you.

2 Ledbury Research and Barclays Wealth (2010) ‘Global giving: The culture of philanthropy’.

3 Cowley, E., Smith, S., McKenzie, T. and Pharaoh, C. (2011) The New State of Donation: Three decades of household giving to charity, 1978–2008, Cass Business School and University of Bristol.

4 Bank of America Merrill Lynch (2010) ‘Study of HNW philanthropy: Issues driving charitable activities among affluent households’.

5 Gates Foundation factsheet, as at 30 June 2011.

6 Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation website – Just Giving pledge, http://givingpledge.org/

7 www.thehunterfoundation.co.uk, as at 30 June 2011.

8 Sir Tom Hunter, announcing his philanthropic intentions in an interview with Robert Peston, BBC News, July 2007.

9 The personal income tax allowance is reduced by £1 for every £2 that taxable income exceeds £100,000 until the allowance is nil and, as a result, the effective marginal rate of income tax on taxable income between £100,000 and £120,000 can be as high as 60%, depending on the source of income ((£20,000 × 40%) + (£10,000 × 40%) = £12,000) so (£12,000/£20,000) × 100 = 60%).

10 The effect of the gift is that Claudia would receive £4,000 as a tax reduction on the grossed-up gift of £20,000 and avoid £4,000 of higher-rate tax due to the reinstatement of her personal allowance of £10,000. This equates to marginal tax relief of 50% on the net cash donation (£8,000/£16,000). When combined with the tax reclaimed at source by the charity of £4,000, this equates to total tax relief equivalent to 75% (£12,000/£16,000).

11 For an explanation of top-slicing relief, see Chapter 15.

12 The Charity Commission regulates charities in England and Wales.